Dear Capitolisters,

Two recent events have me thinking (as one does) about the unseen and unintended harms of inaction, particularly when it comes to government regulation. First, Germany—which is facing a severe electricity shortage because of the Russia conflict—rejected late last week a legislative proposal to maintain several nuclear power plants that were scheduled to be mothballed this year, choosing to burn more coal instead (including some from Russia). Then, this past weekend, the government and economy of Sri Lanka basically collapsed (thousands of protesters even stormed the presidential palace!) because of a wicked combination of crippling debt and major food and fuel shortages.

At first blush, these events don’t really have much in common (other than the Russia-induced global energy crunch), but dig a little deeper and you see that both have at their roots a thing called the “precautionary principle.”

So What’s the Precautionary Principle?

The “precautionary principle” is a regulatory approach under which products and activities are banned unless those wishing to produce, use, or undertake them can demonstrate unequivocally to a regulator that they pose little to no risk to human health, safety, or the environment—even if the economic costs of that regulation are high or the risks are unproven or speculative. There are a lot of variations of this principle, but I think Wikipedia does a good job summarizing the general gist of how it affects public policy (emphasis mine):

The principle is often used by policy makers in situations where there is the possibility of harm from making a certain decision (e.g. taking a particular course of action) and conclusive evidence is not yet available. For example, a government may decide to limit or restrict the widespread release of a medicine or new technology until it has been thoroughly tested. The principle acknowledges that while the progress of science and technology has often brought great benefit to humanity, it has also contributed to the creation of new threats and risks. It implies that there is a social responsibility to protect the public from exposure to such harm, when scientific investigation has found a plausible risk. These protections should be relaxed only if further scientific findings emerge that provide sound evidence that no harm will result.

As the bolder parts hopefully show, the precautionary principle is all about a regulatory system’s default setting (banned where there’s merely a “plausible risk”) and the burdens of proof for overcoming that default (allowed only where “conclusive evidence” has been provided). As Mercatus Center’s Adam Thierer put it, “Where there is uncertainty about future risks, the precautionary principle defaults to play-it-safe mode by disallowing trial-and-error progress, or at least making it far more difficult.”

This hypercautious approach to regulation lurks beneath both of last week’s episodes:

-

In Germany, the plan to rid the country of all nuclear power by this year was implemented in 2011, shortly after the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan. That event caused then-Chancellor Angela Merkel and many other Germans to “to re-evaluate the risks of nuclear power” and, based on those risks, resume an earlier national plan to phase out nuclear entirely—regardless of potential threats to German energy security (e.g., overreliance on Russian natural gas for energy) or possible climate or environmental issues. Spearheading the earlier efforts and the Bundestag vote last week was Germany’s Green Party, which has been “rooted in the anti-nuclear movement” since it started in 1980 and has “played a key role in shaping policy and public opinion on nuclear.” Fast forward to today: Germany—because of the 2011 plan and the Greens’ concerns about nuclear power’s potential risks—finds itself shutting down operational nuclear plants in the middle of a national energy crisis and burning more coal (some of it Russian!) in direct contravention of its climate pledges, even as recent polling shows as much as 70 percent of Germans think “the phaseout should be postponed in light of the country’s dependence on Russia.” Oops.

-

In Sri Lanka, meanwhile, one of the collapse’s main (but certainly not only) drivers was an April 2021 decision by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who resigned on Saturday, to ban imports of chemical fertilizers and shift instead to organic farming—a move that “decimated staple rice crops, driving prices higher” and caused various ripple effects throughout the country. A recent and fantastic deep dive into this policy’s formulation reveals not only some serious magical thinking about whether organic farming could actually generate yields similar to those produced by chemical fertilizers (spoiler: it can’t), but also a muddled and extreme aversion to the latter’s purported health and safety risks. The Ministry of Agriculture, for example, appointed as an advisor “the head of a prominent medical association who had long promoted dubious claims about the relationship between agricultural chemicals and chronic kidney disease in the country’s northern agricultural provinces.” One of the NGOs cheering Sri Lanka’s move to eliminate all synthetic fertilizers (which are widely used around the world), meanwhile, justified the move by citing to the potential (and still-debated) risks associated with a single chemical weedkiller (glyphosate). Now, Sri Lanka has a food shortage.

In each event lurks the precautionary principle: Remote or speculative risks supported government bans on proven technologies that, while certainly not risk-free, also provided major societal benefits—benefits that the regulators essentially ignored. The events also, however, provide new support for some of the biggest criticisms of the precautionary principle.

First, applying a strict version of the precautionary principle can actually lead to bigger risks and more harm than those potentially raised by the banned product/action at issue. In our current cases, the precautionary principle arguably produced more environmental degradation and more human suffering in both Germany and Sri Lanka than allowing nuclear power or chemical fertilizers, respectively, would have done. As is so often the case, regulators at issue ignored their blockades’ inevitable tradeoffs and unseen opportunity costs.

These tradeoffs and opportunity costs are not merely speculative. In one of my favorite recent papers, the authors examined another nuclear power situation—in post-Fukushima Japan—to demonstrate the unintended and unseen costs that the precautionary principle’s extreme risk-aversion can impose on a society. In particular, Japan’s complete halt of all nuclear power within 14 months of the Fukushima accident—driven by a rejuvenated anti-nuclear movement in the country—had serious implications:

The decrease in nuclear energy production did not come without a cost: higher electricity prices. To meet electricity demands, the reduction in nuclear energy production was offset by increased importation of fossil fuels, which increased the price of electricity by as much as 38 percent in some regions. These higher electricity prices led to a decrease in electricity consumption, particularly during times of the year that have the greatest heating demand. Given that interior climate control provides protection from extreme weather events, we find that the reduced electricity consumption caused an increase in mortality. Our estimated increase in mortality from higher electricity prices significantly outweighs the mortality from the accident itself, suggesting that the decision to cease nuclear energy production caused more harm than good.

The authors go on to note that their estimates cover only a few years of higher electricity prices and thus likely understate the extent to which those harms outweigh those caused by the Fukushima accident. Unmentioned, moreover, is the added climate risks that Japan raised by ending nuclear power. They note, for example, that “the share of power generation from fossil fuels rose from 62 to 88 percent in the four years after the earthquake, while the share of nuclear power generation declined from over 30 percent to zero.” Thus, Japan’s nuclear ban not only produced more deaths, but also likely increased carbon emissions, as compared to the status quo. That’s a pretty terrible tradeoff for eliminating the relatively small risk of another Fukushima disaster (which, by even conservative estimates, might happen every 50 years).

Nuclear power is a great example of the precautionary principle’s significant unseen costs and tradeoffs in the energy space, but it’s certainly not the only one. For example, “environmentalists” across the United States—bolstered by risk-averse (and innovation-averse) state and federal conservation regulation—have successfully blocked the deployment of large-scale wind and solar projects because of relatively small (especially on a society-wide scale) conservation risks:

I’m calling for a total and complete shutdown of conservation groups until we can figure out what the hell is going on pic.twitter.com/0RqXVejOes

— Alec Stapp (@AlecStapp) January 18, 2022

(Be sure to read the whole thread to get a feel for the extent of the problem here.)

The U.K., meanwhile, may be rethinking its precautionary principle-based ban on fracking due to serious post-Russia concerns about its impact on British energy insecurity.

It’s tradeoffs and opportunity costs all the way down, folks.

The second big problem with the precautionary principle is that it stifles innovation—again potentially boosting the very risks/harms the policy is trying to avoid. Thierer again:

The problem with the precautionary principle is that uncertainty about the future and risks always exists. Worse yet, defaulting to super-safe mode results in a great deal of forgone experimentation with potentially new and better ways of doing things.

As I summarized in my last book, “living in constant fear of worst-case scenarios—and premising public policy on them—means that best-case scenarios will never come about. When public policy is shaped by precautionary principle reasoning,” I argued, “it poses a serious threat to technological progress, economic entrepreneurialism, social adaptation, and long-run prosperity.”

As I’ve written repeatedly here, we suffered through a lot of this anti-innovation bias during the pandemic, with precautionary restrictions on the deployment of new products—vaccines, therapeutics, rapid tests, etc.—likely prolonging the pandemic and thus causing more misery overall. But perhaps the biggest and worst example of the precautionary principle’s harms to innovation and well-being is the continued global ban on “golden rice,” a genetically modified grain that contains beta carotene and thus could combat vitamin A deficiency in the developing world. Ed Regis, author of a book on the product, explained a few years ago why this product is so important:

Vitamin A deficiency is practically unknown in the Western world, where people take multivitamins or get sufficient micronutrients from ordinary foods, fortified cereals, and the like. But it is a life-and-death matter for people in developing countries. Lack of vitamin A is responsible for a million deaths annually, most of them children, plus an additional 500,000 cases of blindness. In Bangladesh, China, India, and elsewhere in Asia, many children subsist on a few bowls of rice a day and almost nothing else. For them, a daily supply of Golden Rice could bring the gift of life and sight.

The [golden rice] superfood thus seemed to have everything going for it: It would be the basis for a sea change in public health among the world’s poorest people. It would be cheap to grow and indefinitely sustainable, because low-income farmers could save the seeds from any given harvest and plant them the following season, without purchasing them anew.

Golden rice was created more than 20 years ago, has been repeatedly shown to be safe, and has probably been ready for wide-scale distribution for more than a decade. Yet it has only recently won developing country approval for commercial use, and only last year in a single jurisdiction—the Philippines. Why is such a remarkable product still unavailable in most of the developing world, where it’s most needed?

Because, as Regis explained in the Washington Post a few years ago, the precautionary principle blocked it:

The greatest impediment to the release and use of golden rice has been the regulatory apparatus of the health departments and agriculture ministries in the countries where the research was being done as well as in the nations where the biofortified rice was most needed.…

The main source of the problem is the 2003 so-called Cartagena Protocol, a United Nations-sponsored resolution on “biosafety” governing the handling, transport and use of GMOs. A key component of the protocol was its embrace of a precautionary principle stating that “lack of scientific certainty due to insufficient relevant scientific information and knowledge regarding the extent of the potential adverse effects” of a GMO on the environment or human health “shall not prevent” governments from taking action against the importation of the GMO in question.

That sounds like a simple “better safe than sorry” proposition, but in practice it became a bureaucratic doctrine of “guilty until proven innocent.” The worst of it was that the statement allowed the imposition of restrictions on a given GMO in the absence of any actual proof that it would cause harm, or even sufficient reason to believe that it would.

Regis goes on to explain how governments responded to the Cartagena Protocol by being “zealously overcautious” with GMOs, imposing insanely high burdens on their research, development, testing, and commercialization. This included golden rice: “Ingo Potrykus, the co-inventor of golden rice, with Peter Beyer, has estimated that adherence to government regulations on GMOs resulting from the Cartagena Protocol and the precautionary principle caused a delay of up to 10 years in the development of the final product.” As a result of that delay, which still continues today in most of the world, millions of people suffered needless blindness or even death—“a potent illustration of the way erring on the side of caution can sometimes have fatal consequences.”

Indeed.

Finally, it’s important to note that the precautionary principle isn’t just causing big, global problems like those associated with nuclear power, drugs, or golden rice. It also permits an untold number of “little tyrannies” at the state or local level. For example, just a few weeks ago here in North Carolina, several local “wellness” clinics had one of their main offerings—“mild hyperbaric oxygen therapy”—shut down by local fire marshals because the relevant devices allegedly raised fire safety concerns. [Full disclosure: I know the owner of one of these places, but she most certainly didn’t reach out to me about the issue, which I coincidentally noticed in the news.] When you read my local paper’s recent articles on the closures, however, you realize that this is just a classic and frustrating case of the precautionary principle at work: Fire marshals were alerted to the issue by an anonymous tip, not any actual safety incident; the service/device at issue is not expressly prohibited by health regulations or fire codes; the devices have been used tens of thousands of times over decades without any significant fire or other safety events; other U.S. jurisdictions still allow the service, also without incident; among the service’s biggest critics are competitors offering more expensive hyperbaric treatments (how convenient!); and local authorities said they’d let the businesses resume offering the service only if the owners obtain a “formal interpretation from the National Fire Protection Association” that they literally cannot get until at least 2024.

One can certainly question whether this therapy actually works, but it’s not evidently harming anyone and clearly some people like it. (And we allow all sorts of goofy “health” stuff all the time!) Yet the precautionary principle framework bans it anyway, to both consumers’ and providers’ detriment. Read local news long enough, and you see these kinds of things happening regularly—stuff just gets banned because it’s not expressly authorized by some local bureaucrat. Sure, these events might not warrant a flashy Washington Post feature or whatever, but they nevertheless impose real harms on countless people, for no good reason.

Summing It All Up

To be clear, this is not a call for no regulation. Instead, it’s really all about resetting our general regulatory presumptions and burdens. Under the precautionary principle framework now predominantly used by regulators here and abroad, the presumption is in favor of stasis, and private actors bear a heavy burden of overturning or rebutting that presumption: they can’t act unless they unequivocally prove to the state that they pose little to no risk to human health, safety, or the environment—even where there is no clear evidence of harm, just a remotely “plausible risk” of one, and often even in an emergency. My preferred approach, by contrast, simply flips the script (as the kids say): The presumption is in favor of action and the state bears a high burden of proof to stop it; thus, private actors can freely act (and innovate) without express government approval unless regulators convincingly demonstrate that the action at issue is very likely harmful to society on net. Regulators’ focus instead should be on risk mitigation, not risk elimination. Any resulting problems from an innovation or action would therefore be addressed after it’s undertaken (and preferably via private means such as insurance and self-regulation). That said, regulators can and should develop narrow (issue-specific) restrictions to address things (e.g., cloning) that present a clear risk of catastrophic, irreversible harm.

Thierer, much to his credit, has played a major role in advocating this kind of “permissionless innovation” standard. (For those interested in more on this issue, I highly recommend his post on some permissionless innovation guidelines and this recent interview on the pandemic and the precautionary principle.) As he shows, abandoning precautionary regulation would not only be likely to lead to better health, safety, environmental, and economic outcomes than the precautionary principle does, but also prevent the types of anti-competitive, Kafkaesque “little tyrannies” that many Americans, like my poor friend here in Raleigh, endure daily.

Chart(s) of the Week

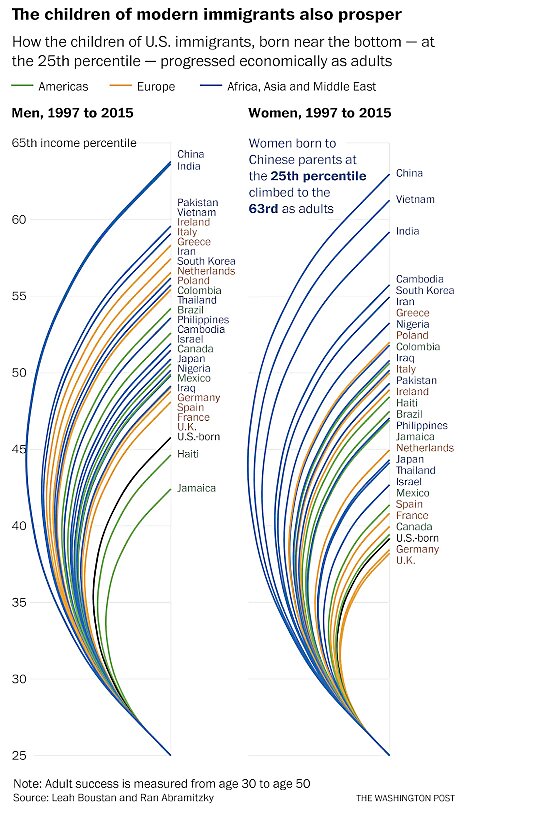

Like previous generations, today’s children of immigrants also prosper (and assimilate):

The Links

U.S. chip subsidy plan makes no sense ( already a glut?)

More FDA lunacy re: monkeypox vaccines approved in Europe

The big risks to America in bringing supply chains home

But supply chains are still improving (for now)

State Department wants a trade deal with CPTPP member New Zealand

Elon versus Twitter, explained

The inflation miscalculation (for some people)

More China warning signs (more) (more)

Welcome to the $1,000 car loan payment

How Twitter affects mainstream media coverage

“Labor Unions Reduce Product Quality”

The infant formula crisis isn’t getting much better (and the FDA’s moves are minor)

Walgreens plans to double robot pharmacy deployment

Solar panel recycling technology could relieve concerns about certain raw materials