As the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) pushes forward with its proposal to increase cryptocurrency surveillance, a past report might offer a clue for how this information may be used in practice. In short, with the IRS set to keep tabs on Americans’ cryptocurrency usage through an expected 8 billion new returns, it seems the Department of Justice (DOJ) may soon have the tools it wants to start confiscating cryptocurrency at an unprecedented rate.

The issue stems from a 2022 report written by the DOJ in response to Executive Order 14067. For those who might not remember, Executive Order 14067 was President Biden’s first major cryptocurrency initiative. Although many people initially feared an impending crackdown was coming, the executive order largely delayed making sweeping changes by first calling on agencies to issue reports to inform future policies around cryptocurrency and related issues.

The report, written by the DOJ, covered a vast range of topics. Largely falling into four categories, the recommendations spanned ways to aid prosecutions, ways to improve investigations, ways to expand penalties for cryptocurrency-related crimes, and ways to increase the resources available for government employees.

What’s most interesting for the present conversation, however, is where the DOJ argued for increasing its ability to seize cryptocurrency.

For example, the report states that “it is critical that the United States have the authority to forfeit the proceeds of cryptocurrency fraud and manipulation as a means of deterring such activity and divesting violators of their ill-gotten gains.” Therefore, the DOJ recommends expanding its authority over criminal, civil, and administrative forfeiture.

The DOJ has claimed these updates are necessary because the department’s experience with cryptocurrency-related cases has “revealed limits on the forfeiture tools used to deprive wrongdoers of ill-gotten gains and, in certain cases, restore funds to victims.”

Yet this argument is difficult to understand considering how much and how often the government has been able to seize cryptocurrency over the years. In fact, the report itself mentions such cases. Between 2014 and 2022, the FBI seized around $427 million in cryptocurrency. The IRS seized another $3.8 billion between 2018–21.

With more than $4 billion on hand, the DOJ’s argument that the U.S. government is struggling to seize cryptocurrency is just not as apparent as the report’s recommendations make it out to be.

Still, the IRS’s broker proposal puts the DOJ’s report into a new light given the vast surveillance that the proposal would likely create — vast surveillance that could be used to start confiscating cryptocurrency at an even greater rate.

The problem is what’s referred to as administrative forfeiture. As Nick Sibilla explained in Forbes when the report first came out, “Under ‘administrative’ or ‘nonjudicial’ forfeiture, the seizing agency — not a judge — decides whether a property should be forfeited.” In other words, agencies do not need to prove to a judge that a crime was committed in order to seize the property.

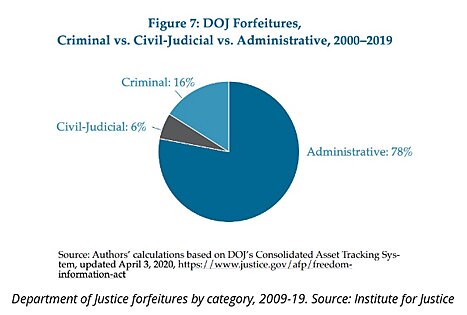

The DOJ commended this process for promoting an “efficient allocation of government resources” while discouraging “undue burdens on the federal judicial system.” In fact, this process seems to be the DOJ’s preferred practice given that administrative forfeitures made up 78 percent of its forfeitures between 2000 and 2019.

With the IRS collecting vast amounts of new information on Americans’ cryptocurrency use, it’s possible that the DOJ may “suddenly” find vast new arenas for cryptocurrency confiscation. And again, it’s important to stress that these confiscations don’t have to start with an actual crime being committed—just the mere suspicion.

Given how often misunderstandings surrounding cryptocurrency have fueled headlines, it’s not difficult to imagine how such suspicions could emerge. For example, it was less than a month ago that more than 100 members of Congress cited a flawed report to call for a crackdown on cryptocurrency.

Considering the IRS proposal in this light helps to showcase one of the major risks of mass data collection. Whether it’s the DOJ seeking to expand its confiscation activities, the IRS looking to increase audits, or a hacker seeking out an exploit, massive government databases create tempting targets for both internal and external abuse.

If the IRS pushes forward with its proposal, cryptocurrency users should keep a careful eye on how that data is ultimately used by the government at large.