From early 2021 through mid-2022, surging inflation occurred alongside an increasing level of corporate profits. Politicians like Elizabeth Warren and some economists, such as Isabel Weber, smelt a rat. If prices are determined by firms’ costs plus a markup, then doesn’t a world of increasing profits and high inflation signify that greed, or profit-seeking, is causing inflation? As Democratic politician Jim Himes asked one of us during a Congressional hearing: firms ultimately choose to raise their prices to enjoy these extra profits, don’t they?

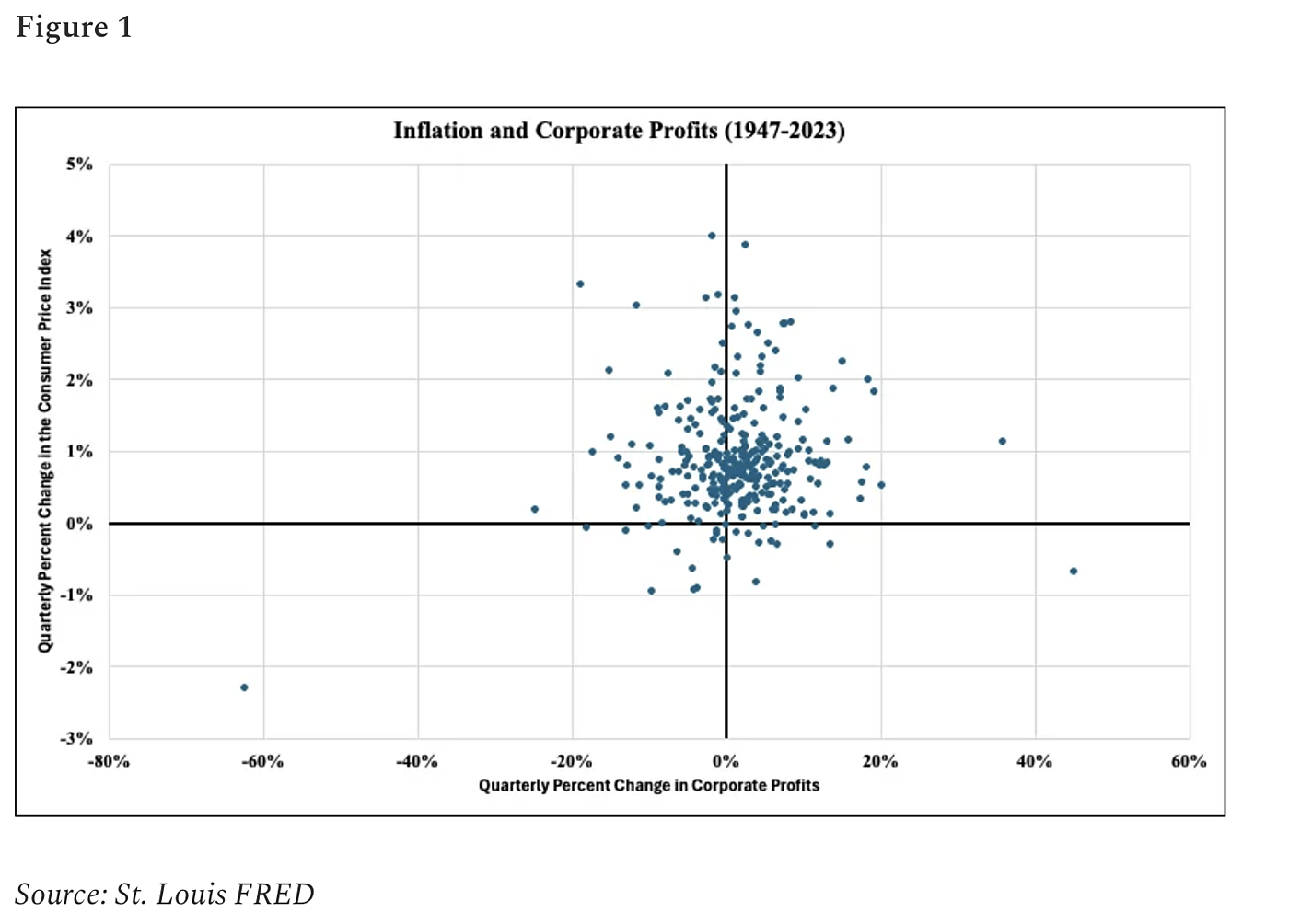

Looking historically, inflation and changes in corporate profit levels do not show much of a correlation at all (see Figure 1). Such evidence hardly suggests that, in general, profits drive inflation. But were things different more recently? Was corporate profit-puffing behind the surge in the price level? No. In fact, theory and evidence suggest that both sharply increasing profits and rising inflation reflect a third factor: excessive macroeconomic stimulus driving high spending across the economy.

The economics of this are pretty simple. As Brian Albrecht explains in his chapter in The War on Prices, corporations are disciplined in what they can charge by both competition and customers’ willingness and ability to pay. If one firm decides to jack up prices, they’d not only risk losing customers to their rivals, but any existing consumer paying the higher price would have lower money balances left over to spend on other goods and services, reducing demand and so prices for other items. Hence, some companies just unilaterally deciding to charge higher prices can’t cause economy-wide inflation — a sustained rise in the general price level — because, absent higher overall spending, other prices will fall.

No, the only way greed could explain the recent inflation would be if firms across many industries suddenly used their market power to withhold real output, raising product prices by reducing total production. Some allege corporations used the excuse of rising gas prices and supply chain woes to do just that. Yet in both 2021 and 2022, real output, or real GDP, grew strongly, rebounding more quickly after the pandemic than forecasters had expected. There’s little evidence, in other words, that market power was suddenly flexed, if such implicit collusion between businesses were ever really feasible.

The most robust explanation for strong real output growth, rising profits, and inflation all happening simultaneously is instead soaring total spending in the economy. That is precisely what happened in 2021 and 2022. Nominal GDP — i.e. total spending on final goods and services — exploded, after vast monetary and fiscal stimulus.

Just before the pandemic, the Federal Reserve was projecting that long-run spending would rise by 3.9 percent annually. In 2021 and 2022, total spending growth averaged 9.9 percent, more than two and a half times the Fed’s projection. In short, the Federal Reserve oversaw a huge increase in the money supply through the pandemic that, coupled with vast government borrowing, manifested in a rapid growth of spending on final goods and services — boosting demand far above its pre-pandemic trend and so raising the price level.

Such an environment can lead to higher short-term profits too because, in a range of sectors, retail prices tend to increase more quickly in response to rising spending than firms’ wages and input costs. The latter are often governed by contracts that are negotiated infrequently, meaning that when output prices rise, real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) wages and other input prices will fall. As a result, corporate profits can increase, at least until wages and input prices adjust.

People’s expectations about inflation play a crucial role in how wages and other input prices are set. In early 2021, few workers and input suppliers were expecting high inflation. They negotiated wage and other input price contracts on that basis. With spending rising and pushing up product prices, alongside stickier wages and input costs, many firms’ profits thus rose temporarily. In fact, as it became clear that the general price level was rising, some corporations no doubt raised their output prices in anticipation of their input and wage costs then going up, contributing further to a temporary profit spike.

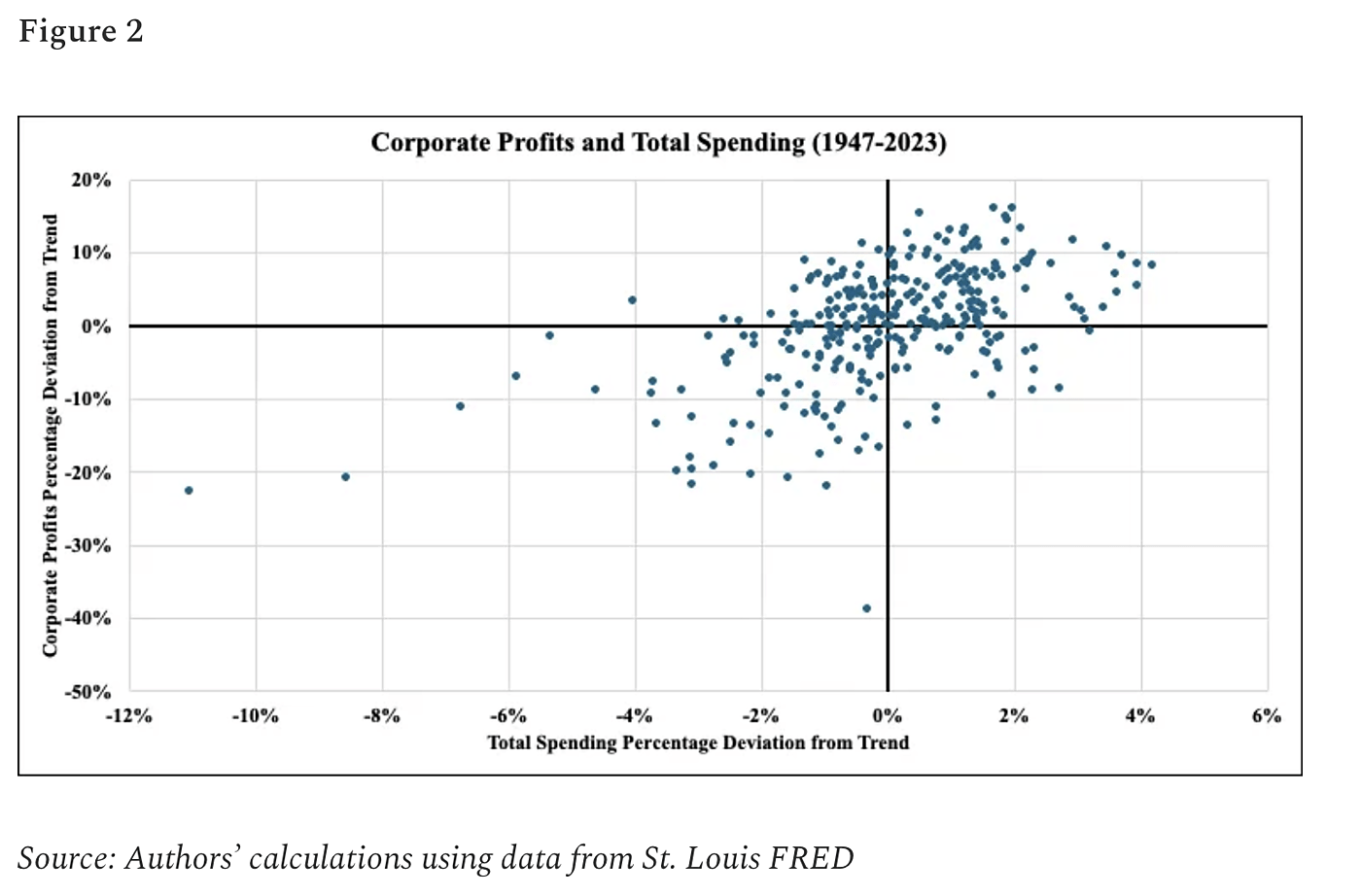

The key point is that this wasn’t a function of greed, market power, or profit-puffing. The ultimate cause was a macroeconomic policy that had led spending to explode, forcing up all prices in the medium-term. And there is historical evidence for this short-term relationship between spending and profits too. One implication of this theory is that when total spending deviates positively from trend, corporate profits are likely to as well. Indeed, this positive correlation is precisely what we see in the post-war data for the U.S. (see Figure 2). Even relatively small deviations from trend in total spending are associated with large deviations in corporate profits.

Critics of this evidence might argue that we risk confusing correlation with causation. They might claim, for example, that deviations in corporate profits from trend might instead be causing total spending to deviate too. Economic theory, however, tells us to be skeptical of such an interpretation.

Other than money supply growth, the growth of total spending depends on the growth rate of money velocity, which measures how quickly dollars change hands. Short-term interest rates are a key determinant of velocity. As the rate of return paid by alternative assets rises relative to money, velocity will tend to rise and vice versa. A rise in market power — if it affected interest rates at all — would likely lower these rates, reducing velocity and, therefore, total spending. Thus, there is little reason to expect that increasing corporate profits would drive total spending higher.

Those same critics might also claim that our view fails to account for the fact that corporate profits as a share of total spending have yet to return to their pre-pandemic level. But this may merely reflect that the surge in total spending put the U.S. on a higher price level path and that wages and other input prices still haven’t fully caught up. Once they do, this share is likely to return somewhere closer to its pre-pandemic level.

Understanding what drove inflation and profits matters, because politicians have been deflecting blame for inflation away from macroeconomic policy errors towards corporations. They have used accusations of greed and profiteering to push for price controls and excess profit taxes. Such policies are not only economically destructive, but would have failed to address inflation’s underlying cause—namely, a surge in total spending brought on by excessive monetary and fiscal stimulus.

With polls now showing that the public also sees corporations as the primary boogeyman for inflation, we thus risk leaving this episode with a faulty history embedded in the public consciousness. This popular profit-led inflation narrative not only lets today’s politicians and central bankers off the hook for their mistakes, but risks creating a fertile environment for terrible policy next time inflation hits.