Dear Capitolish,

I hope you all had a very happy Vax Day yesterday and are eagerly awaiting your jabs in the coming months. I know I am. We’ll talk more about the COVID vaccine in the future, but for now I’d like to change gears and talk about something totally different: farm subsidies. (I know, I know—it’s almost too much excitement for one newsletter, but let’s all try to keep it together, shall we?)

Anyway, you may be surprised to learn that, in the midst of a global pandemic and continuing trade war(s), the USDA just announced that American farmers are having a banner year in terms of income and profits:

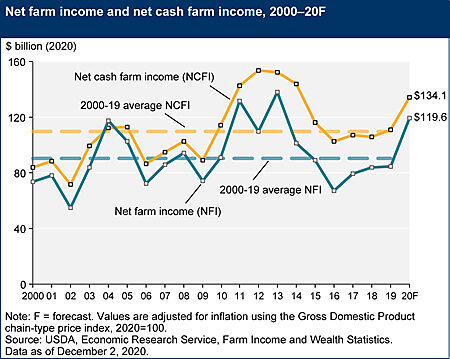

U.S. net farm income this year will jump 43% to $119.6 billion, the highest inflation-adjusted level since 2013, the government said Wednesday in a report. The projected surge occurred as the virus pandemic roiled the food-supply chain in the spring, driving grain prices down and meat costs higher.…

U.S. agriculture is on track for one of the three most-profitable years in a half century. Adjusted for inflation since 1973, projected net farm income in 2020 will be surpassed only by 2011 and 2013 figures.

The chart and underlying data are available from the USDA here:

So what’s driving these major increases? Back to Bloomberg:

The latest data show the increasing dependence of growers on government assistance after three years of trade and Covid-19 aid on top of traditional subsidies. Farmers face a murky outlook next year if the Biden administration adjust[s] payments.

Direct government aid, accounting for 39% of net farm income, rose to a record $46.5 billion from $22.4 billion last year. …

Yes, you read that right. This year, farmers (on net) will derive almost 40 percent of their income directly from the U.S. government. Forty percent.

As we’ll discuss, a good chunk of these government payments come from the CARES Act, but much of it flows from earlier government programs. And all of it is due to American farmers’ historically disproportionate pull in the U.S. Congress—pull that has resulted in decades of massive, harmful, and (mostly) unnecessary taxpayer support. At least it can provide some broader lessons about U.S. subsidies.

So let’s jump right in.

History and Context

The United States has subsidized American farmers in some form since the New Deal era (the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933) and today doles them out primarily via one vehicle: the farm bill—a large and complex piece of legislation that’s renewed every five or six years and includes two main parts: (1) various types of support for domestic agribusiness (i.e., farm subsidies); and (2) “nutrition” (mostly the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program). Although we think of the farm bill as a subsidy bill, it’s actually heavily tilted toward nutrition—in the last (2018) farm bill, for example, more than 75 percent of federal outlays were actually for SNAP and related programs.

We’ll talk more about this balance in a moment, but for now let’s focus on the subsidies. As noted by the Cato Institute’s Chris Edwards, U.S. government support for farmers is “deep and comprehensive”: via the farm bill, the government “protects farmers against fluctuations in prices, revenues, and yields,” and “subsidizes their conservation efforts, insurance coverage, marketing, export sales, research, and other activities.” Back in 2014, Congress made some significant revisions to the subsidy programs—limiting direct payments and subsidies to certain farmers while amplifying federal crop insurance—but the overall amount of money remained relatively steady in subsequent years..

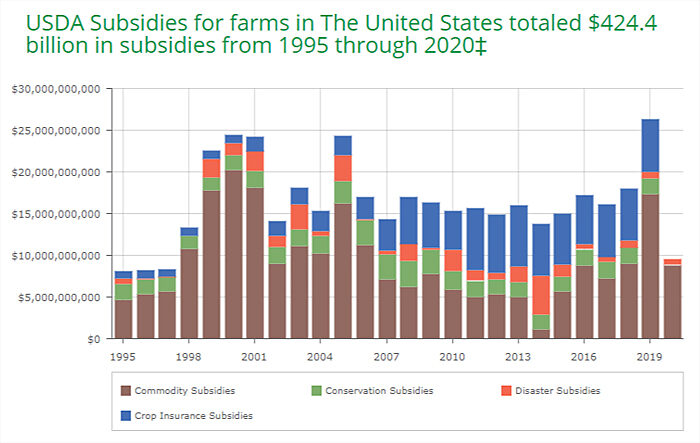

That amount is substantial: according to the Environmental Working Group’s compilation of Department of Agriculture data, for example, the federal government has provided approximately $424.4 billion in current-dollar subsidies—crop insurance, commodity payments, conservation payments, and disaster payments—to U.S. farms since 1995 (the 2020 data are incomplete):

Given the duration and magnitude of federal support, there’s perhaps no U.S. industry that has attracted more taxpayer subsidies—more consistently—than agribusiness.

The EWS data also show that U.S. farm subsidies have been historically concentrated among a few states (Texas and the “Farm Belt”), a few recipients (big farms and banks), and a few commodities (especially corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, and rice). We’ll discuss in the following sections how these concentrations raise all sorts of concerns.

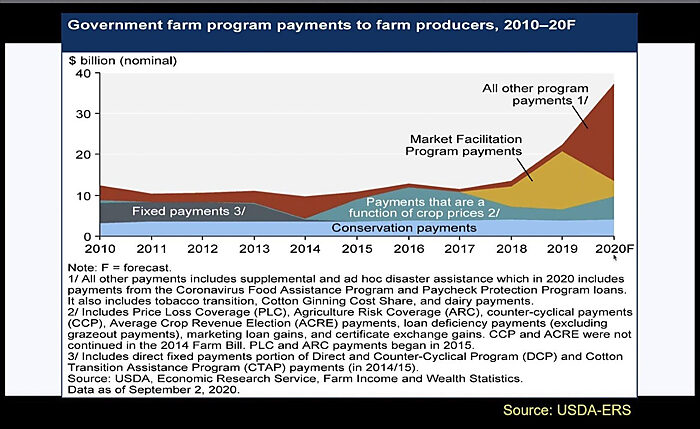

Anyway, as already noted, farm subsidies remained relatively flat over the last decade but then exploded during the Trump years because of his trade wars (“market facilitation program” payments) and COVID-19:

We’ve already gone over the trade war stuff, so feel free to look back at what a mess that’s been for farmers (who faced heightened bankruptcies in 2019). The COVID relief, on the other hand, would be a bit more defensible if it were allowing farmers to break even, not make near-record profits. As already discussed, that’s not the case. In fact, the eye-popping numbers above don’t include USDA loans and recently expanded federal crop insurance, which provides billions of additional dollars in federal support each year.

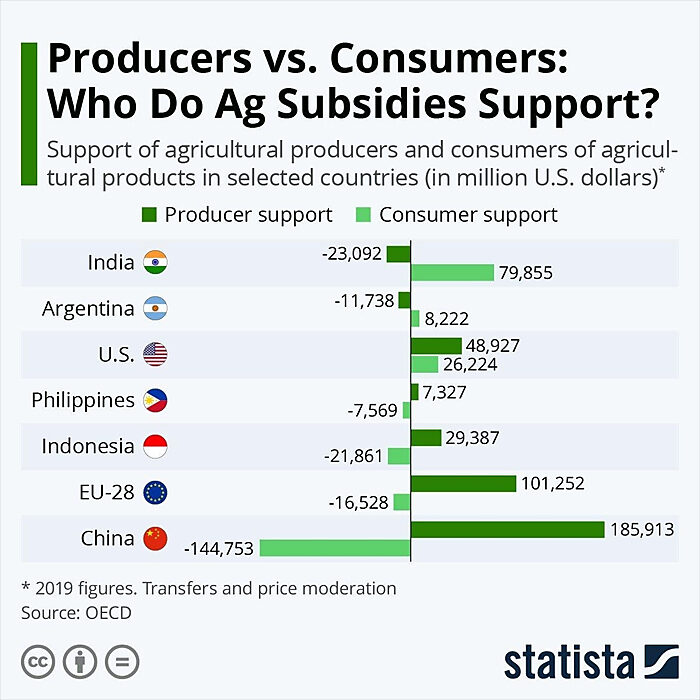

The U.S. government certainly isn’t alone when it comes to subsidizing farmers. As this recent infographic shows, for example, plenty of developed and developing countries provide significant government funds for producers or consumers (though the U.S. is pretty unique in doing both):

Yes, But Still …

Nevertheless, that other countries subsidize their farmers is a pretty terrible excuse for the U.S. government to subsidize ours, particularly given the numerous problems that American farm subsidies create or support, including:

Regressive subsidization.

Beyond the mere budgetary strains imposed by the tens of billions of dollars that the government must borrow every year to subsidize our farmers, Edwards notes that those subsidies are also going to relatively rich people: farm household income is historically much higher (40 percent to 50 percent higher) than the income of the average U.S. household, and subsidies are typically concentrated among the largest farms. Subsidies also have been shown to disproportionately benefit landowners (even ones who are exiting production). In fact, past subsidy recipients include several billionaires (yes, billionaires with a “B”), and Trump’s trade war subsidies have only exacerbated the issue. As one University of Illinois examination of farm incomes notes, this trend is important not just for equity reasons, but because “farm programs were adopted in part as a response to the poverty of the U.S. farm population, which was 25% of U.S. population in 1930.” Not so anymore.

Harm poor countries.

Because the United States is a major exporter and importer of farm products, federal subsidies have a disproportionate effect on global agriculture markets and, in turn, farmers in developing countries.. A classic example is how African cotton farmers were hurt by U.S. cotton subsidies, which increased global production of cotton, thereby lowering the world price to levels at which less productive cotton farmers in West Africa couldn’t compete. As one study concluded, “[b]etween 2 million and 3 million farms in West Africa rely on cotton as their main source of cash income, and they compete directly with subsidized US cotton. Not surprisingly then, lower world cotton prices harm millions of households and more than 10 million people across the region.”

Farm subsidies also act as a “non-tariff” barrier to imports of food and feed: By making U.S. farm goods cheaper to produce than in foreign markets, farm subsidies—like tariffs—raise the price of foreign goods relative to U.S. goods and thus reduce imports. Cutting U.S. farm subsidies would thus help some of the poorest people and regions in the world (especially since agriculture historically plays a foundational role in their economic development).

Trade conflicts.

Given how American farm subsidies can hurt farmers in other countries, it’s no surprise that they’ve also created trade conflicts. For example, the United States’ unwillingness to agree to a lower cap on domestic farm supports was one of the main reasons that the World Trade Organization’s “Doha Round” of global trade negotiations fell apart last decade. (WTO members can subsidize their farmers up to a certain agreed level.) This is a dumb economic strategy: because WTO talks are comprehensive and reciprocal (we trade our concessions for their concessions), the United States’ recalcitrance on our relatively small agriculture industry helped sandbag potential gains for larger U.S. manufacturers and service providers in key foreign markets like China or India. Surely, other countries also contributed to the collapse of the WTO’s negotiating arm, but the U.S. position on ag subsidies (and a couple other issues) removes our ability to pressure them on it.

Our farm subsidies also generate formal trade disputes at the WTO or in national-level “countervailing duty” cases, which allow governments to unilaterally impose duties on subsidized imports. The risk of anti-subsidy actions (whether at the WTO or in CVD cases) is particularly a concern for export-oriented farmers who could see their subsidy gains offset by foreign market losses, and it should grow in the wake of the new trade war and COVID subsidies. U.S. farm policy also leads to bizarre trade outcomes like the one where the Obama administration, after losing a WTO dispute to Brazil over cotton subsidies, didn’t eliminate them but instead decided to subsidize Brazilian cotton farmers (to the tune of $300 million!). Sigh.

Economic distortions.

As you can imagine, injecting billions of government dollars into U.S. and global agriculture markets creates all sorts of economic distortions, such as (1) supply gluts (remember that mountain of surplus cheese?); (2) support for unhealthy crops like corn and derivatives like high-fructose corn syrup (which is also boosted by sugar protectionism), potentially encouraging obesity; (3) discouraging farmers from taking out private insurance; and (4) harming the environment.

This last point is especially noteworthy and problematic, as Edwards explains:

Subsidies cause overproduction, which draws lower-quality farmlands into active production. Areas that might have been used for parks, forests, grasslands, and wetlands get locked into agricultural use. AEI scholars note that subsidizing crop insurance encourages farmers “to expand crop production on highly erodible land.” Lands that would have been used for pasture or grazing have been shifted into crop production.

Subsidies may induce excessive use of fertilizers and pesticides. Producers on marginal lands that have poorer soils and climates tend to use more fertilizers and pesticides, which can cause water contamination problems. Sugar cane production has expanded in Florida because of the federal sugar program, for example, and the phosphorus in fertilizers used by the growers causes damage to the Everglades.

Finally, subsidies may discourage crop rotation in favor of planting only a subsidized crop, which in turn can lead to increased use of fertilizers. The boom in corn production driven by subsidies and the ethanol mandate is apparently generating pollution problems in the Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico.

The farm bill’s recent shift to crop insurance could actually exacerbate these and other environmental problems: The government backstop encourages farmers to engage in riskier behavior (locating in floodplains, etc.) and discourages them from engaging in practices—such as planting “cover crops like rye or clover, which anchor soil and nutrients during the off-season, and help stabilize yields through years both dry and wet”—that would protect them “from the very losses they end up needing crop insurance to recoup.” This creates a vicious cycle: increased environmental damage increases the taxpayer cost of subsidizing crop insurance (and providing other disaster relief), which leads to more environmental damage and more taxpayer money and.… you get the idea.

Political problems.

Finally, U.S. farm subsidies breed all sorts of political dysfunction. The programs have become notorious examples of government waste and abuse, yet reform has proven difficult, if not impossible. Why? Because decades of government funding and industry capture created an seemingly-unstoppable political machine—the last farm bill got 87 yeas in the Senate and 369 in the House—capable of not only killing real reforms, but also maintaining or even expanding costly boondoggles like the ethanol program. Perhaps the best example of this capture is the aforementioned “nutrition” (SNAP) section of the farm bill:

By 1973, the number of congressional districts dependent on farming were shrinking, but farm bills had grown in cost and frequency. How to maintain support for the shrinking farm constituency? By adding food assistance—at the time, food stamps—to the package. The shotgun marriage of farm aid and food stamps meant rural and urban members of Congress came together to get the farm bill over the finish line. This has been true for every bill since…

[N]utrition programs are used as a shield to avoid scrutiny of inefficiencies, waste, and even outright fraud running rampant in the so-called farm safety net. Against the farm bill? Don’t you care about food insecure families?

As noted in the linked article, this dynamic actually allowed lawmakers to expand eligibility for farm subsidies in 2018—even reversing some of the reforms made in the previous cycle.

As farmers become even more dependent on Washington for their incomes (and as those incomes become even less connected to the market), these political pressures may only increase in the future. Indeed, as noted by Bloomberg above and elsewhere, there’s now a big question as to whether—after two-plus years of massive “emergency” payments—Congress will be able to muster the political will needed to turn off the spigot. And for good reason.

Summing It All Up

So, American farm subsidies strain the federal budget, line the pockets of relatively wealthy farmers, harm poor countries, fuel trade conflicts, and cause all sorts of economic, environmental, and political problems. They’re also unnecessary: New Zealand and Australia, for example, eliminated all or most of their farm supports decades ago and are still major global producers, and powerhouse Brazil is also on the lower side of the global subsidy ledger. There’s no reason to think that the United States—given our wealth, massive natural advantages, and sky-high agricultural productivity (see, e.g., U.S. crop yields across various categories)—couldn’t do the same. Indeed, New Zealand’s subsidy reforms actually helped its producers become more innovative and productive (funny how free market competition does that).

Unfortunately, the aforementioned political dynamics and massive current payouts make such reforms unlikely anytime soon—even as farmers enjoy near-record incomes. And therein lies a broader lesson for those who today suggest we turn other American industries into Big Ag: once the subsidy train gets rolling, it’s often difficult—if not impossible—to stop it, regardless of the overwhelming merits of doing so.

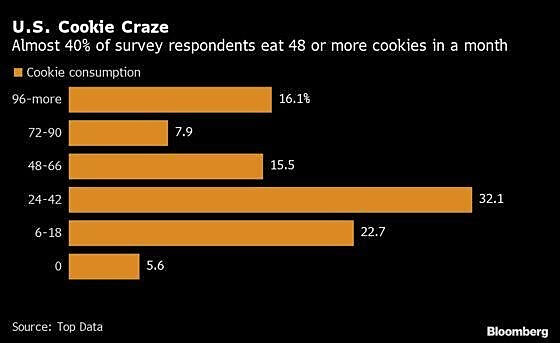

Chart of the Week

“96-more”?!? (source)

The Links

Visualizing Trump’s restrictions on legal immigration

China’s cracking down on entrepreneurs and private businesses

Etsy has already done $600 million in face mask sales this year

Achieving herd immunity in the USA

Student loan forgiveness benefits the rich

On “corporate social responsibility” and Milton Friedman

“This time the airlift will be run by logistics firms who make smarter customers”

“[F]ree trade may be far more popular than many politicians in Washington seem to believe”

“Covid-19, Remote Work Make Austin a Magnet for New Jobs” (more here)