Dear Capitolisters,

An unexpected joy of parenthood has been watching my daughter do silly stuff that I did as a kid but from the perspective of a (cynical, budget-conscious) adult. Among the most delightful of her youthful endeavors have been many absurd “inventions” that required vast amounts of time and household materials (scotch tape, poster board, old charging cables, etc.) to—at best—re-create things we already had lying around the house. Of course, it wasn’t great to later discover my empty stapler (or whatever), but any temporary inconveniences were dwarfed by listening to a small child excitedly explain her creation. Sometimes, she’d even end up making something—a pencil holder, a new dog leash/grooming belt combo, etc.—that kinda (sorta) made sense and actually (again, sorta) worked. Regardless, her process was endlessly entertaining.

But that process doesn’t make for good economic policy, where—unlike a child’s experiments, or even my adult gardening hobby—costs do matter and expected outcomes are tangible, not emotional. In the economic policy world, it’s important not only that something arguably good happen, but also that it was effectuated in a good and reasonable way.

This calculus is not exactly groundbreaking stuff: It’s Econ 101 and something most adults consider every day. Why are so many people on the right and left ignoring it and, perhaps even worse, calling such childishness “economics”?

What Is Economics?

Google around for a short definition of “economics,” and you’ll have a lot to choose from. Perhaps the best one-sentence version comes from Lionel Robbins’ An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science: “Economics is the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between given ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.” ChatGPT provides a pretty good answer too: “Economics is a social science that studies how individuals, businesses, governments, and societies make decisions about how to allocate their scarce resources. These resources can include labor, capital, land, and natural resources, and they are considered scarce because there are not enough of them to satisfy all the wants and needs of individuals and societies.” The American Economics Association provides a similar one-liner: “[Economics is] the study of scarcity, the study of how people use resources and respond to incentives, or the study of decision-making.”

Reviewing these and other sources reveals some consistent themes: First and most obviously from the lines above, resources (money, time, labor, etc.) are finite and have many uses. That means economists examine not merely an outcome (“a given end”) but also its “relationship” to a decision or policy devoting the resources to achieving that result and whether, all things considered, it was worth all those resources—in terms of direct costs, opportunity costs (whether the resources could have been better deployed elsewhere in the economy), and the inevitable tradeoffs and unintended consequences that accompany all decisions, political or otherwise.

Thus, economic analysis doesn’t simply point to some event and some subsequent outcome, and boldly proclaim that the former caused the latter. (Indeed, there’s a whole hilarious website that generates these “spurious correlations” on demand.) Economists don’t just declare a policy change—a new tax or subsidy, for example—a “success” or “failure” because something good or bad, respectively, happened thereafter. Doing that ignores whether the result at issue was already happening before the policy was implemented; whether unrelated stuff—wars, recessions, famines, other policies, whatever—occurred around the same time and actually caused the result; whether policymakers actually intended the result (or just got lucky); whether the data at issue are of high quality and truly representative; where there’s a strong and intended connection between a policy and an outcome, how much it all cost (overall and for particular groups); and, relatedly, what didn’t happen as a result of the policy choice.

Adhering to these basic principles, economists develop elaborate, often very clever, methodologies to determine both whether a certain policy likely caused a certain desired outcome (more jobs, more output, etc.), and at what cost—both the direct, “seen” costs to the parties involved (consumers, business owners, taxpayers, etc.) and the indirect, “unseen” ones (including opportunity costs). Economist Tim Taylor recently provided a great, easily accessible example of how this kind of economic analysis is contemplated and carried out with respect to the minimum wage, walking readers through a new study out of Minnesota that used high quality, non-public data from the state and two different analytical techniques to determine the effects of a minimum wage that Minneapolis phased in over time. The study’s results are interesting (spoiler alert: Wages increased, but jobs and hours worked declined; average workers came out even, but workers in the most-exposed jobs came out worse), but Taylor’s main point was to caution against simplistic approaches—“X then Y, so X caused Y”—to complex policy issues and to instead show how real economics works: i.e., “serious studies using a variety of methods” that “show genuine tradeoffs.” Plenty of other examples of this kind of rigorous economic work abound. (I liked this one recently on food deserts.)

Redefining ‘Economics’?

Some of this is technical and jargony, but much of it doesn’t require an economics degree or years of training—just some common sense. Most of us (excluding Homer Simpson) inherently grok the difference between causation and coincidence. And we also consider (usually) unseen costs. Consider, for example, how wealthy Europeans used to grow pineapples:

In temperate Europe, pineapple growing was more of an elitist hobby than true agriculture. Early attempts required tremendous effort and expense to produce even a handful of pineapples per season. Massive greenhouses, heated by stoves, were required to produce a specimen at Chelsea Garden in 1723. The palace horticulturists at Versailles were able to produce one ten years later. Over the next 70 years, various English aristocrats would build heated glass “pineries” on their rural estates, most with limited success in actually farming the fruit.

Under a simple approach, a single pineapple grown at Versailles was a great success: Louis XIV wanted a pineapple, and he got one. It doesn’t take a trained economist, however, to understand that this result came at a cost that far exceeded the fruit’s actual value, especially when considering what else those resources—time, money, manpower, etc.—could have generated instead. To paraphrase Mel Brooks, it was good to be the pineapple-eating king, but not so good for everyone else.

Unfortunately, many on the right and left seem to have discarded these considerations for a framework that treats outcomes—intended or not, costs and consequences be damned—as all that matters. On the right, for example, the folks at American Compass and their allies have embraced a so-called “conservative economics” (or “common good economics”) which, among other things, explains that past experiments with protectionism and industrial policy were great successes because good things happened thereafter. For example:

- U.S. automotive quotas in the 1980s “saved Detroit” because, while they may have raised Japanese car prices a little, foreign automakers subsequently opened factories here. Never mind, then, the myriad economic analyses showing a weak causal connection between much of the foreign investment at issue (it also came before and after the quotas were in place); immense seen and unseen costs generated by the quotas (all cars got more expensive for many years, and Big 3 automakers misallocated their windfall profits); numerous unintended consequences (e.g., boosting foreign automaker finances and competitiveness); or quota proponents’ failure to achieve their stated goal of boosting unionized employment at, and the competitiveness of, Big 3 automakers. The quotas, in fact, were so good for Japanese automakers that the Japanese government kept them in place for years after the Reagan administration wisely abandoned them. The Big 3 automakers only became competitive decades later. The policy remains, quite literally, a textbook example of how not to do trade policy, yet… here we are.

- French subsidies to Airbus were another industrial policy “success” because Airbus sells more planes than the free-market U.S. competitor, Boeing. Yet, as the Mercatus Center’s Veronique deRugy has explained, a basic examination of Boeing’s own government dependence and the Airbus subsidies’ immense economic and political costs—including collateral damage caused by a decades-long trade skirmish with the United States—implodes this characterization. Elsewhere, the Peterson Institute’s Adam Posen notes how U.S. and European government support for Boeing and Airbus stifled global aviation innovation while generating substandard products (like the now-decommissioned Airbus A380), cronyism and government budget overruns, and systemic risks. One might conclude that having a big, global aircraft manufacturer is worth these significant costs, but the “conservative” declaration of success seemingly never considers them.

- Finally, the “American system” of protective tariffs in the 1800s “built America,” mainly because the U.S. rapidly industrialized while the tariffs were in place. As economic historian Phil Magness has detailed, however, the system’s actual history reveals the founders’ distaste for the system, its numerous “ignominious legacies,” and rampant corruption and cronyism that accompanied U.S. tariff policy up to the disastrous days of Smoot-Hawley. Other economic historians, meanwhile, have found that tariffs played a minor, perhaps net negative, role in U.S. development during the 19th and early 20th centuries. As Dartmouth economist Doug Irwin (whose book is the definitive history of U.S. trade policy) [blank]put it in one of his papers on the subject, “That there is a correlation between high tariffs and economic growth in the late nineteenth century cannot be denied. But correlation is not causation.” Indeed.

In short, just because this stuff is called “economics,” doesn’t mean it actually is.

Unfortunately, a similarly simplistic framework has found a home on the left, too. For example, Chinese “green industrial policy,” has been deemed an “amazing” success because pervasive government subsidies and protectionism supposedly made China a global player in solar panels, electric vehicles, and related technologies. Yet, even granting that these policies actually built the Chinese industry, bold declarations of “success” fail to consider their true costs, some of which have been recently detailed:

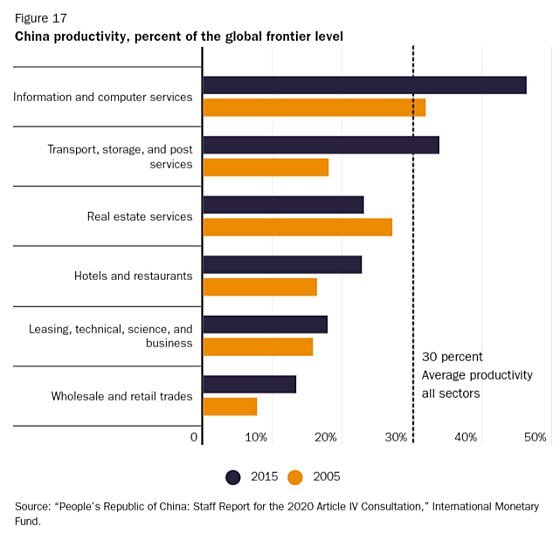

- In two recent papers (2022 and 2023), economist Lee Branstetter and colleagues examined how Chinese industrial policy—including on green goods—has affected productivity and innovation in targeted sectors. In the first, they found that Chinese industrial policy between 2007 and 2018 had a terrible track record of “picking winners” (more productive firms) or turning “losers” into winners. Instead, Beijing subsidized bigger, less productive firms and ones in declining industries like mining. Even worse, subsidized firms got less productive after receiving government cash. In a recent interview, Branstetter highlights these policies’ opportunity costs: “The money that’s given to prop up failing firms is money that cannot be given to support the technology leaders of the future, and the more you do the former, the less resources you have to do the latter.”

- Examining China’s “Made in China 2025” program, which started in 2012 and targeted a wide range of strategic national industries, the second paper found that subsidies were mostly ineffectual in stimulating statistically significant increases in patenting in China or in the United States, or in either labor productivity or total factor productivity. The resources were wasted while, as Branstetter noted in the same interview, generating massive geopolitical costs: “the problem for the Chinese government is not only have they spent money and at least not yet apparently achieved the desired innovative outcomes, but they’ve alienated and angered their trading partners and arguably brought down on Chinese firms and the Chinese economy a whole range of sanctions whose costs, at least in part, probably have to be added to the cost of the resources that were directly expended on.”

- A third new paper from this May comes to similar conclusions about the efficacy of Chinese industrial policy. The authors examined 2008 subsidies to Chinese firms that generated lots of patents. The result was, indeed, more patents but ones of much lower quality (in part because less innovative firms started buying junky patents from firms outside the targeted sectors so that they could qualify for subsidies). Overall, they estimate that the program generated a “net social return” of negative 19.7 percent (“that is, the society would be better off without this subsidy program”)—a total that, they suggest, could be even worse if “corruption, lobbying, or incompetence” were considered. The authors thus conclude that “the presence of even a mild government failure could convert an otherwise well-justified industrial policy from success to failure.” (Nothing to worry about then!)

These thoughtful economic analyses—while welcome—aren’t really groundbreaking. As I wrote in 2021, Chinese industrial policy “successes” have not only been matched (if not exceeded) by failures in key industries like semiconductors, but also accompanied by huge direct costs and broader harms—resource misallocation, corruption/graft, overcapacity, financial instability, etc.—that “hinder rather than accelerate China’s economic development.” With both productivity and debt being two of China’s biggest long-term headwinds, industrial subsidies are proving to be an anchor, not accelerant, for Chinese innovation, economic growth, and geopolitical power—despite the outward appearance of a few recent “successes.”

Second, when people say “of course it’s happening, it’s being subsidized” — well, yes, but the size of the boom has surprised everyone, including industrial policy proponents. So there’s real news here 2/

— Paul Krugman (@paulkrugman) June 7, 2023

There is no tangible data yet in hand that supports these premature verdicts of success. It is not at all surprising that access to low-cost financial support from the government is popular, but that only means the costs to the federal government might exceed what was projected at enactment. In fact, Goldman Sachs analysts expect the subsidies provided through the IRA to cost $1.2 trillion over a decade, which is several hundred billion dollars more than the official forecast predicted last year. Further, the costs to consumers from the IRA’s subsidy-focused strategy for slowing climate change exceed what would occur if U.S. policymakers chose instead to achieve the same pace of progress through a carbon tax. In other words, paying companies to change their business models is simply less efficient than price signals for bringing about the desired outcome.

Brookings economists (and IRA supporters) have also acknowledged that a carbon tax likely would have produced better environmental outcomes, while also cautioning that the law’s “industrial policy components” might alienate trade partners and “raise costs more than is socially beneficial, undermining the climate benefits of the tax credits.”

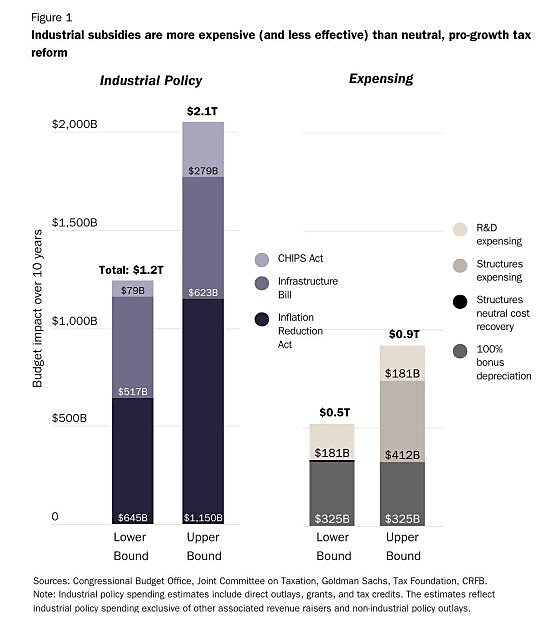

Meanwhile, my Cato colleague Adam Michel and I recently provided another IRA alternative—“full expensing” of various business deductions—that would have boosted U.S. high tech manufacturing and economic growth but at a lower budgetary cost and with far fewer potential distortions:

Today’s IRA cheerleaders consider none of this.

They also ignore, as Veuger and Capretta outline, many other pitfalls that have plagued past U.S. industrial policy efforts and that economists will have to eventually consider. This includes 1) implicitly penalizing enterprises that don’t get subsidies (who now “face higher relative costs of labor and supplies because they must compete for employees with firms in subsidized sectors who are paid in part through funds received from the government, not customers”); 2) increasing prices—see, e.g., semiconductors—for American companies and consumers (who “must purchase products made with domestic content requirements, which necessarily means higher-efficiency options are pushed aside and competition is reduced”); 3) increasing corruption and cronyism as companies try—as they so often do—to make “temporary” subsidies permanent or to expand them to cover their own businesses; and 4) discouraging innovation, as “government barriers will make it more difficult for new and unsubsidized entrants to upend settled business relationships” and “political connections and lobbying prowess will rise in importance, while technical competence and efficiency will fall.”

China-style policies producing China-style outcomes.

Maybe our grand, subsidy-driven “industrial transition” will be worth it in the end (outside of favored industries, the sector is today struggling mightily), but declarations of victory at this stage are absurd.

Summing It All Up

Back in that interview, Branstetter closed with some broader points that revealed an economic approach to grading industrial policy in China, here, and elsewhere:

I think it’s fair to point out that this kind of industrial policy is hard for everybody. … Many in Washington looked to Japan as an outstanding example of a country that had skillfully used industrial policy to turn itself into an economic superpower. But the evidence that supported this view was largely anecdotal, and when economists actually dug into industry-level and firm-level data and started testing the hypothesis that Japanese government subsidies, or other forms of goodies, were going to the productive industries and made them even more productive, the economists found results that are very similar to the results my co-authors and I are finding.

He also cautioned against grading industrial subsidies’ success on nothing more than a correlation between an industrial policy and desired end (“With enough subsidized water, you can grow cotton in the Arizona desert.”), and he explained how anecdotal “successes” can mask much bigger failures—less innovation, lower living standards, more geopolitical conflicts, and, over the long term, even the ultimate failure of preferred industries at issue. (See, for example, what’s happening today in Brazil.) And he noted how the Chinese government could have devoted the scarce resources spent on Made in China 2025 and other industrial policy projects to educational and other programs that would’ve produced much better outcomes for China and the world.

All of that is, as Lionel Robbins tersely summarized long ago, standard economic reasoning. A child can be forgiven for missing it, but what’s the adults’ excuse?

Chart of the Week