For the last week or so, the U.S. Senate has been considering one of the largest “industrial policy” packages in recent history. In particular, the United States Innovation and Competition Act of 2021 (formerly known as the “Endless Frontier Act” or EFA) is intended to boost federal funding for applied industrial research and development by tens of billions of dollars. Well, at least it was. The bill has morphed considerably since it was first delivered to the Senate Commerce Committee for markup under “regular order.” Today, the 1,400-plus page bill is as much—if not more —about other stuff than it is about subsidizing “key technology focus areas” like artificial intelligence, advanced semiconductors, and quantum computing. And even the policies targeting those key areas have been watered down and changed.

All of this has shocked and exasperated many industrial policy advocates who saw the EFA as an essential part of future U.S. industrial competitiveness. I, as you can imagine, tend not to agree with their plans or their sense of urgency (and the data tend to support me—see this week’s links), but that’s beside the point, at least for today. Instead, the whole episode provides us with a golden opportunity to dig into a field of economics—public choice theory—that helps to explain a lot of what goes on in Washington and one of the main reasons why designing and implementing good industrial policy in the United States is so darn difficult.

What Is ‘Public Choice Theory’?

I briefly addressed public choice in February when discussing the Jones Act but never provided the basics, so let’s start there.

Public choice theory is a branch of economics developed by economists James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock and elucidated in their 1962 book The Calculus of Consent. Public choice hit the big time in 1986 when Buchanan won the Nobel Memorial Prize in economics for his work in the field. In general, public choice takes the same principles that economists use to analyze people’s actions in the private market and applies them to people’s actions in the public sphere. Thus, political actors are presumed to act not in the “public interest” but in their own rational self-interest and thus to use the political systems in which they operate to make themselves, not the general public or nation as a whole, better off. In this context, elected officials’ primary goal is reelection, whereas bureaucrats strive to advance (or protect) their own careers. Surely, political actors have motivations other than self-interest, but the general public choice framework assumes the latter until proven otherwise. As Buchanan put it, the theory “replaces… romantic and illusory… notions about the workings of governments [with] … notions that embody more skepticism.”

Today many of us may take such skepticism for granted, but questioning the image of the altruistic “public servant” was pretty radical when Buchanan, Tullock, and other public choice scholars first started doing it. Nevertheless, once you’re aware of public choice theory’s basic tenets, you see it everywhere in public policy—especially in both the design and implementation of American industrial policy. On the former, elected officials frequently advance legislative policies that confer concentrated benefits upon small, homogenous, often local interest groups and impose diffuse (but larger) costs upon the general public, because only the small groups have sufficient motivation to follow the issues closely and apply political pressure (lobbying, campaign contributions, and votes) based thereon. Because the public is “rationally ignorant” about these policies (and thus does not tie their votes or contributions to them), elected officials act rationally in supporting them, even when the policies are known to produce net losses for the country. This “collective action” problem not only generates “pork barrel” projects (often through “logrolling” bargains, in which legislators trade votes on each other’s pet project), but also makes reform or elimination of these programs exceedingly difficult, regardless of their efficacy.

Implementation of industrial policies can also fall victim to politics, even in systems designed to be insulated from elected officials. Research shows, for example, that government agencies’ agendas often mirror those of the members of the congressional committees that primarily oversee them—members that often actively seek out these committee assignments in order to affect the regulatory agencies beneath them. Thus, the same political pressures that distort elected officials’ creation of and support for a certain industrial policy can similarly distort the federal bureaucracy’s work to effectuate it. Similarly, numerous studies show that agencies can become “captured” by motivated special interest groups (or their elected benefactors) who use the agency to further their own narrow interests at the broader public’s expense. Even where political pressure is limited (often by design), capture can occur where bureaucrats lack the same level of specialized knowledge as the entities they’re regulating and thus grow to rely on those entities for both information and manpower (aka “the revolving door”).

The U.S. political system amplifies the public choice hurdles facing industrial policies (and others) for two big reasons. First, large segments of Congress are replaced (or threatened with replacement) every two years and the president every four. This dynamic not only injects “short-termism” and uncertainty into the decisionmaking process, but also makes elected officials more risk-averse and focused on reelection instead of the long-term national interest. Second, the U.S. has a well-developed lobbying and interest group system, which would inevitably affect (and likely deteriorate) the design and implementation of any significant industrial policy. Economist Mancur Olson explained how these two dynamics undermined U.S. industrial policies back in 1986, and both are almost certainly more intense today.

How Public Choice Confounds U.S. Industrial Policy

Past U.S. industrial policy efforts show how public choice issues can thwart planners’ intentions, especially in the high-tech space. For example, in critiquing the Endless Frontier Act’s structure back in 2020, technology experts Patrick Windham, Christopher T. Hill, David Cheney noted that “US efforts in the 1990s to identify ‘critical technologies’ did not succeed, partly because it is hard to predict which technologies will be most valuable in the future [note: this “Knowledge Problem” is another common industrial policy hurdle] and partly because decisions about R&D funding priorities inevitably become political, as groups and leaders vie to have their favorites supported.”

Once legislation is passed, moreover, politics can still intervene. In the 1991 book, The Technology Pork Barrel, for example, the authors—sympathetic to industrial policy—examined six federal programs from the 1960s and 1970s intended to develop commercial technologies for the private sector. They found that none were truly successful, while four were “almost unqualified failures,” costing billions, crowding out more meritorious R&D projects, yet enduring long after fiscal, technological, and commercial failure was established—a survival owed to political pressure (especially financial benefits accruing to numerous congressional districts) and captured regulators.

To block a potential National Science Foundation purchase of a supercomputer made by Cray’s Japanese rival NEC in the 1990s, for example, the House of Representatives “passed legislation sponsored by Rep. David R. Obey (D‑Wis.), whose district includes a Cray facility, that would virtually ensure the contract goes to Cray,” and the captured Commerce Department imposed record-setting anti-dumping duties of 454 percent on Japanese supercomputer imports in 1997. (Members of Congress routinelyinfluence U.S. agencies’ anti-dumping determinations—either by informal pressure or by changing the governing statutes—in order to enrich their corporate or union constituents.) For other examples of tech industry capture and corporatism during the last heyday of U.S. industrial policy (the ‘80s and ‘90s), check out High Tech Protectionism by AEI’s Claude Barfield.

More recently, studies have shown that various Department of Energy projects funded by the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) had significant political, not scientific, motivations—with project funding oftenlinked to lobbying expenditures or campaign contributions. Solyndra got the headlines, but there were plenty of other messes (see, for example, “clean coal” calamities in Illinois and Mississippi). DoE loan guarantee programs from the same period also suffered from other political problems, such as non-economic objectives like job protection and local sourcing (“Buy American”) rules. Other recent research finds that politically connected firms (as measured by contributions to home state elections) were “64 percent more likely to secure an ARRA grant and receive 10 percent larger grants” than other, less-connected companies.

And then there’s the whole Emergent Biosolutions fiasco: a “longtime government contractor” that invested heavily in lobbying; had effectively “captured” the government agency (the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority) authorized to disburse and monitor pandemic-related contracts; and, despite repeated failures, was rewarded with a $628 million contract to manufacture COVID-19 vaccines.

Surely, not every U.S. industrial policy effort has become a public choice poster child, but the theory has proven remarkably prescient overall. As The Technology Pork Barrel authors put it, numerous U.S. industrial policy experiences “justify skepticism about the wisdom of government programs that seek to bring new technologies to commercial practice.” (If only!)

So What Happened to the Endless Frontier?

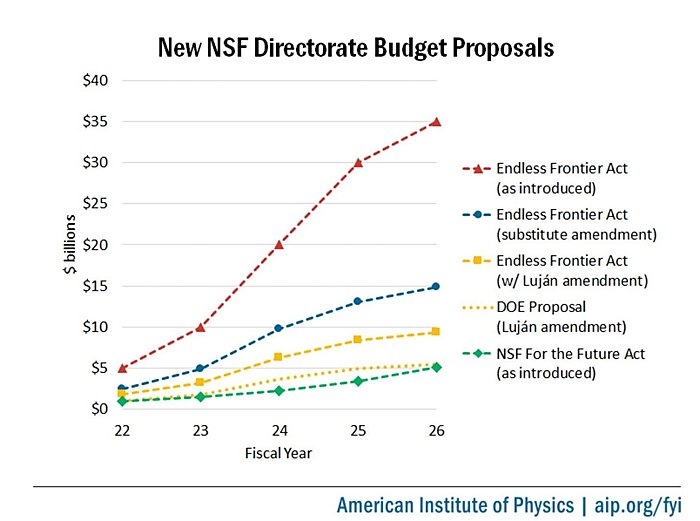

The Endless Frontier Act (EFA) obviously hasn’t been implemented yet, but its Senate consideration is consistent with the aforementioned theory and practice. For starters, the actual innovation section of the bill has changed dramatically in terms of scope and operation: instead of $100 billion going to the National Science Foundation, “[w]hat we have now are single-digit percentage boosts to the NSF’s funding, some money out of left field for the Department of Energy, and a plus-up for National Labs like Los Alamos (thanks to the National Labs Caucus which, perhaps unsurprisingly, seems more focused on pushing money to their states’ arguably duplicative labs than addressing domestic innovation challenges).”

Maybe, as Yuval Levin argues, the National Labs changes are a good thing, but a press release issued by the National Labs Caucus senators makes clear that their motivation wasn’t the “public interest” but simply bringing home the bacon for the labs in their states. It also appears that the NSF itself was involved in lowering the price tag, “given worries that the EFA would give the Technology Directorate too much autonomy and detract from the agency’s traditional focus on inquiry-oriented science in favor of applied research and technology.”

But that’s just the EFA sections. Senators have also added all sorts of other provisions that are mostly (or entirely) unrelated to the original EFA, including:

-

$52 billion in new subsidies for the domestic semiconductor industry, $39 billion of which is for commercial (non-defense) manufacturing facilities and workers, not bleeding-edge R&D. We’ve already gone over how most of these subsidies are dubious at best (Intel agrees!), but Sen. Chuck Schumer’s latest press release touting the benefits for New York chip companies is a useful addition (as is this recent op-ed on the subsidies’ inevitable inefficacy). New to the semiconductor subsidy package, however, is $2 billion for “legacy chips” (read: old, low-tech stuff) that U.S. automakers need—an amendment helpfully offered by Michigan Sen. Gary Peters because it “would boost the U.S. auto industry in his home state of Michigan.” And, just for the record, it’s not only libertarians opposed to this obvious corporate welfare:

Yes. Congress should work to expand U.S. microchip production. No. As part of the Endless Frontiers bill we should not be handing out $53 billion in corporate welfare to some of the largest and most profitable corporations in the country with no strings attached.

— Bernie Sanders (@SenSanders) May 24, 2021

(Scott citing Bernie. Wonders never cease.)

-

Peters’ other amendment, applying “Davis-Bacon” wage and work requirements (which labor unions love) to the aforementioned semiconductor subsidies—reportedly violating a deal with Senate Republicans on that very issue.

-

Washington Democratic Sen. Maria Cantwell’s amendment adding $10 billion to NASA’s budget “to give Blue Origin a shot at winning the lunar landing contract NASA has already awarded to SpaceX at a fraction of the cost, all while requiring NASA to continue developing an unnecessary launch system that Boeing just happens to have the contract for.” Blue Origin was founded by Cantwell constituent Jeff Bezos.

-

New, protectionist country of origin labeling requirements for online retailers (unlike brick-and-mortar shops), but excepting cooked king crab and tanner crab to win the vote of Alaska’s Dan Sullivan.

-

More restrictive—and thus more destructive—“Buy American” rules for federal construction projects (which the steel industry, of course, cheered) and new rules for federal procurement of domestic PPE (which the textile industry, of course, cheered).

-

A new ban on U.S. sales of shark fin. (I got nothin’.)

I’m confident that there’s more nonsense in there, but the bill is more than 1,400 pages long, so it’s almost impossible to sort through all of it. And more amendments are on the way.

Industrial policy advocates have expressed shock and dismay at the various Senate Committees’ “logrolling” efforts, but their surprise is unwarranted. Indeed, this kind of behavior is exactly what the literal dictionary definition of public choice tells us will happen:

The logic of collective action explains why farmers have secured government subsidies at the expense of millions of unorganized consumers, who pay higher prices for food, and why textile manufacturers have benefited significantly from trade barriers at the expense of clothing buyers. Voted on separately, neither of those legislatively enacted special-interest measures would pass. But by means of logrolling bargains, in which the representatives of farm states agree to trade their votes on behalf of trade protectionism in exchange for pledges of support for agricultural subsidies from the representatives of textile-manufacturing states, both bills can secure a majority. Alternatively, numerous programs of this sort can be packaged in omnibus bills that most legislators will support in order to get their individual pet projects enacted. The legislative pork barrel is facilitated by rational-voter ignorance about the adverse effects of legislative decisions on their personal well-being. It also is facilitated by electoral advantages that make it difficult for challengers to unseat incumbents, who, accordingly, can take positions that work against their constituents’ interests with little fear of reprisal.

And we’ve known for months now that every industry group and lobbyist in town was gearing up for this moment. Throw in the fact that this is (supposedly) must-pass, bipartisan “China legislation,” and it’d be shocking if all the logrolling and pork didn’t happen.

At this point, advocates are left to hope that this is all cleaned up by the House. (Good luck, as they say, with all that.)

Summing It All Up

So U.S. industrial policy has a long history of struggling to overcome political pressures, just as public choice predicts, and the EFA is no different. None of this means that all legislating is bad, or that politicians don’t at least occasionally vote in the national interest. Instead, the public choice framework simply adds another hurdle—along with things like the “knowledge problem,” seen and unseen costs, and misaligned incentives—to designing and implementing commercial policies specifically intended to beat the admittedly messy and imperfect situation that the market generates. It’s imperative that we understand these risks before supporting policies that, while they might look good on paper, could easily morph into a counterproductive boondoggle—one we’ve seen countless times with respect to U.S. industrial policy. Buchanan’s “skepticism” is most definitely warranted.

We tolerate these risks and costs when there’s a real crisis or when the subject is national defense, where government involvement is both necessary and inevitable (because it’s the sole consumer of defense-related goods) and public support is more widespread and enduring. (We also tend to get better results in that case.) But there’s little excuse to do so for industrial policy—especially when there’s plenty of evidence (see links below) that America’s urgent manufacturing or investment problems are neither as urgent nor as problematic as advocates claim.

Chart(s) of the Week

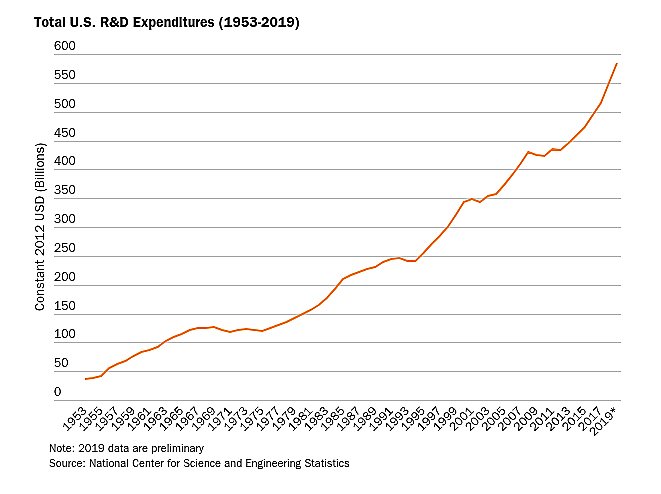

U.S. R&D spending is … pretty good, actually:

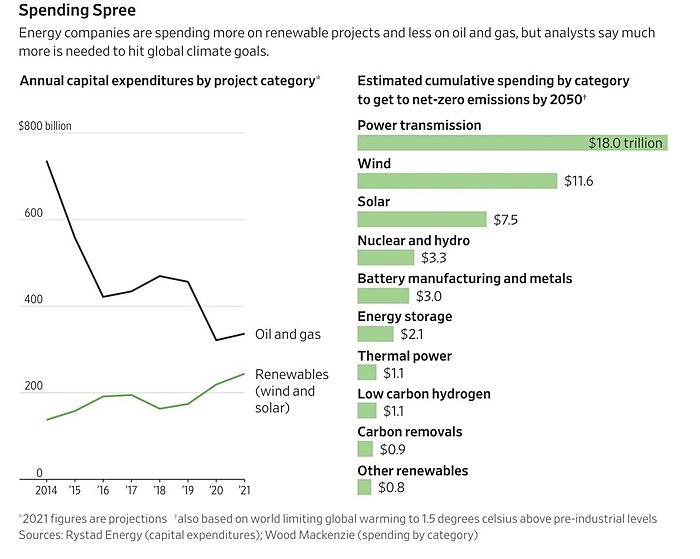

And private investment in clean tech is skyrocketing:

The Links

Me on semiconductor R&D, U.S. R&D generally, and lumber tariffs

New paper from Cato’s Terence Kealey on the spotty U.S. record of public R&D funding

Cato’s Chris Edwards has more on R&D subsidies

Free Cato book: “The Most Common Arguments Against Immigration and Why They’re Wrong”

Small biz struggling to match the big guys’ pay raises

VC investment set a record in 2020 ($130 billion)

Study: Imports support 21 million American jobs (on net)

Study: Childcare isn’t a major driver of the worker shortage (related)

Price controls doing what they do

Pandemic aid drives hospital consolidation

Will pandemic-era telemedicine deregulation survive?

Decades of federal support still hasn’t revived Youngstown

Ohio’s vaccine lottery seems to be working

Americans are (still) paying the China tariffs

Will U.S.-based foreign multinationals be excluded from U.S. infrastructure projects?

U.K. proposes new tariffs as retaliation against U.S. steel/aluminum tariffs

Hijacker abandons school bus following incessant kid questions

Sometimes, you just have to deal with my blatant Texas Rangers homerism