To fuel Thanksgiving-mentum through this holiday transition week, we’ll dig into our incredible modern food abundance (yes, even amid recent inflation) and how globalization helps fuel it.

My Cato colleague Sophia Bagley and I explored this issue in-depth in a recent essay for Cato’s Defending Globalization project. We explained that for all the talk about container ships and trade agreements and wonky economic metrics, there’s probably no better symbol of real globalization—the (mostly) seamless exchange of stuff, ideas, cultures, and people—than the food we eat every day. Consider, for example, your local watering hole:

There, you’ll almost certainly find something on the menu that didn’t originate in the United States. If you’re at an ethnic restaurant, it’ll be almost everything listed, but even the classic American bar and grill serves nachos or egg rolls or French fries (that probably originated in Belgium). The food you’ll eat, meanwhile, will contain numerous imported ingredients—spices, sauces, or produce that don’t grow locally this time of year (if ever)—and likely imported plates, glasses, and flatware. Maybe you also enjoy imported beer or Australian wine (though even your Miller Lite comes from Czech hops and German yeast). And it’s a good bet that at least one person in the kitchen—and often a waiter or even the owner—was born outside the country. You might think you’re having a good ol’ American cheeseburger, but you really have the whole world on your plate.

As Bagley and I explain in the essay, food has always been global (and globalized), but the relatively recent combination of new technologies (containerized and refrigerated transport, the internet, etc.) and policy liberalization (lower tariffs, trade agreements, etc.) has undoubtedly accelerated the worldwide proliferation of foodstuffs, cuisines, related supplies, foodies, and even Western capitalism around the world. As a result, most Americans today enjoy a level of “food abundance” that our grandparents could only dream of. And as someone who loves to eat, I’m particularly pleased with this delicious state of affairs.

Bagley and I provide a lot of fun examples of how “food globalization,” for lack of a better term, enriches our daily lives, but a couple new reports on pineapples (yes, pineapples) provide another fantastic example worth exploring today—one that teaches the benefits of open international and domestic trade, the follies of U.S. protectionism, and a bunch of wonky economic stuff along the way.

Our Global Journey to Grocery Abundance

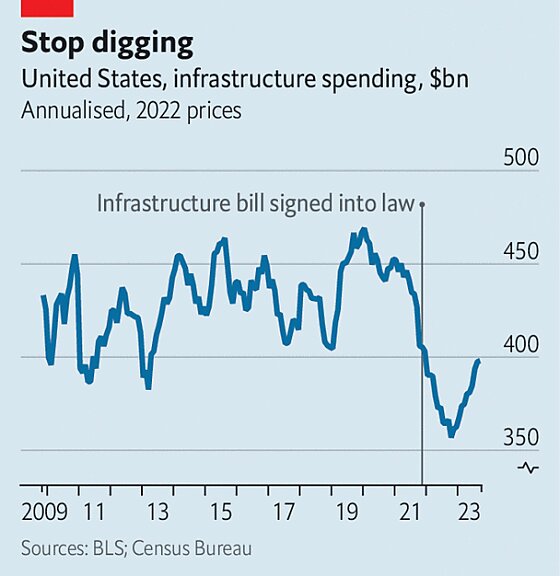

It’s easy to stroll through your local supermarket’s aisles and grab products from distant corners of the globe without a second thought. Yet this abundance is a relatively recent phenomenon. Between 1975 and 2022, the number of products in an average U.S. supermarket increased from 8,948 to a whopping 31,530. Not all that increase is due to globalization, of course, but much of it is. As shown below, imports of essentially every food type have increased substantially in recent the decades:

Some of these gains reflect Americans’ increasing appetites for foreign cuisines and the related explosion of such items in U.S. grocery stores. As I wrote here last year, these foods are now so common and desired that American grocers can’t fit them all in the “ethnic food” aisle, where buyers and sellers actually prefer them, while Asian supermarkets like H Mart and Patel Brothers have exploded in popularity.

But there’s probably no bigger symbol of U.S. grocery abundance—and grocery globalization—than the produce section. American supermarkets in 1980, for example, carried an average of 100 different produce items, and the number approached 250 by 1993. Even then, however, many fruits and vegetables were limited to North American growing seasons, and few here had even heard of products like rambutans, lychee, or jackfruit. A casual stroll through the same aisles today, by contrast, reveals incredible variety, driven in large part by global trade and Americans’ globalized taste buds. According to the FDA, in fact, 55 percent of fresh fruits and 32 percent of fresh vegetables today are sourced from abroad. And we don’t give any of this abundance a second thought, even though Americans living just a few generations before us would think we lived like kings.

In the case of food, however, we actually live much better. And fresh pineapples show how.

As Laura Williams explained in a recent article for the American Institute for Economic Research, the pineapple has historically been a very expensive symbol of wealth and opulence in the Western world. Originating in the Americas, the fruit was introduced to Europe via the Columbian Exchange. Unlike many other tropical fruits, however, pineapples don’t ripen further after being picked, so they can’t be picked early and then allowed to ripen on the long voyage to the Western world. Only a few fresh(ish) pineapples made it to 16th century Europe via the slow, unrefrigerated ships of the time. They were considered a rare delicacy and could, even into the 18th century, cost up to $8,000 a pop (in today’s dollars). Pineapples were so prized, in fact, that Europeans rented them by the hour, used them as showy displays of wealth (“where guests could marvel at their exotic strangeness”) and only ate them when they’d become borderline-rotten or had been preserved at the source in jellies or liquors. Pineapple imagery, meanwhile, adorned housewares and architecture as a symbol of prosperity—a tradition that persists even today in many parts of the United States.

As I noted back in June, the wealthiest European aristocrats finally got sick of waiting around for pineapple ships to arrive, so they tried to grow the tropical fruit in temperate Europe by using giant, stove-heated greenhouses called “pineries.” (Occasionally, they’d even be successful in actually producing one.) This, as I explained, may have impressed the locals, but it was terrible economics:

Under a simple approach, a single pineapple grown at Versailles was a great success: Louis XIV wanted a pineapple, and he got one. It doesn’t take a trained economist, however, to understand that this result came at a cost that far exceeded the fruit’s actual value, especially when considering what else those resources—time, money, manpower, etc.—could have generated instead. To paraphrase Mel Brooks, it was good to be the pineapple‐eating king, but not so good for everyone else.

So, that’s where global trade comes in: As time wore on and technology improved, pineapple trade between tropical climates and temperate ones increased substantially. In the late 19th century, canning technology allowed almost-fresh pineapples to be shipped from the source to Europe and the United States. Baltimore soon became the pineapple canning center of America, but product quality was generally poor because pineapples had to be shipped green from the Bahamas or Cuba to prevent rotting during transit. Nevertheless, canned pineapples were—as I, growing up in the 1970s and 80s, can attest—basically Americans’ only regular option for the next century.

Then, things radically changed. As Williams notes, today you can occasionally find fresh pineapple on sale for less than a dollar. Or, if you prefer, you can get a $2.40 one delivered today via Doordash:

Put another way, the median American blue collar worker today has to work a mere 5 minutes to afford what the wealthiest Europeans once spent a fortune to eat maybe—maybe!—a couple times per year. That’s incredible stuff.

Today’s Fresh Pineapple Abundance

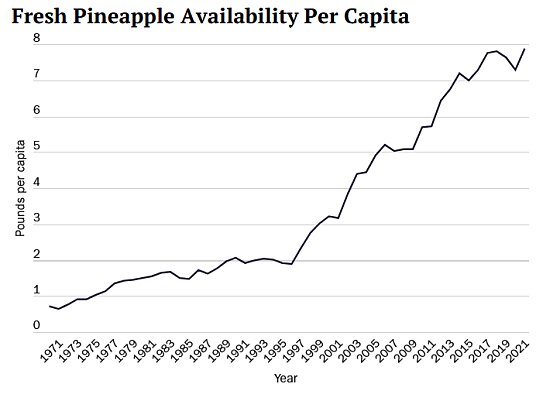

Before we get to how this abundance happened, let’s first document it. According to the USDA, the annual availability (effectively a proxy for consumption) of fresh pineapple in the United States soared from less than a pound per capita in 1970 to almost 8 pounds in 2021. As shown in the chart below, this growth really took off in the late 1990s after plateauing around 2 pounds since the late 1970s. Almost all of this is from imports, especially those from Costa Rica, which accounted for 87 percent of the record high of 2.73 billion pounds of pineapples imported into the U.S. in 2022. Overall, fresh pineapple imports today are more than six times greater than in the 1990s:

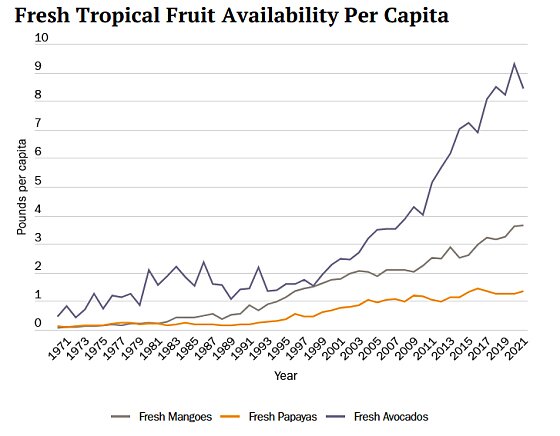

Other tropical fruits have followed a similar trend, with papayas, mangoes, and avocados increasing in availability per capita significantly in the past decades:

Today, fresh pineapple is so abundant in our grocery stores that it has the second-highest retail loss rate for fresh fruits, meaning that American retailers discard pineapple because of spoilage, misshapenness, or overstocking at a rate higher than most other fruits. In just a few decades, Americans went from marveling at the occasional fresh pineapple at their local supermarket (e.g., my mom in 1982) to worrying about food waste from throwing out all the extras those same stores couldn’t sell.

The Drivers of Pineapple Abundance

At its most basic level, today’s pineapple situation is a classic case of comparative advantage.

Growing tropical fruit in temperate climates is—as noted above—a terrible use of finite resources and was for ages limited to only those people who didn’t care about such waste. Thus, it makes economic sense for Europeans and Americans to devote those resources to more productive endeavors (which, in this clear case, is basically anything!), while using the money they make from those tasks to buying pineapples grown in places better (much better) suited for such production.

It turns out that Costa Rica is one of those places—if not the place—not only because of natural factors (rich biodiversity, tropical climate, fertile soil, etc.) but also social ones (democratic traditions, secure property rights, stable economy, etc.). As a result, the nation has over time specialized in pineapple production and has emerged as the global leader. By focusing on this industry and expanding agricultural trade with other countries, the USDA has found, developing countries like Costa Rica enjoy widespread economic benefits—gains that fuel development (rising GDP and living standards) as labor and resources from agriculture eventually shift toward higher-value manufacturing and services. And we Americans, of course, benefit too—from not only tasty and cheap pineapple but also more time to devote to leisure or work activities we’re comparatively better at performing. (If interested, my Cato colleague Gabby Beaumont-Smith’s new essay on the real consumer benefits of trade explores this theme in depth.)

But this is just pineapple theory. Three things turned it into pineapple practice.

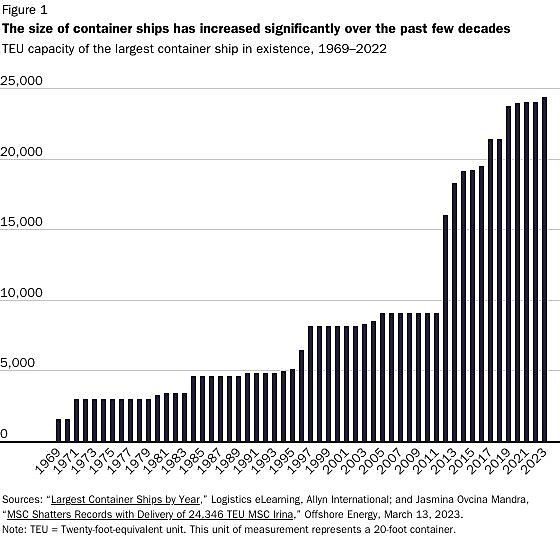

First, there’s the technology. Incredible developments in both containerized shipping and refrigeration today allow the notoriously fussy pineapple, which can spoil in a week at room temperature, to be shipped fresh anywhere in the world just a couple weeks after being picked. These technologies were first developed in the mid-20th century (containers in the 1950s and “cold supply chains” in the 1970s) but, as my colleague Colin Grabow explains in a new essay, are constantly being improved even today:

Then there are advances in industrial farming. It takes around 14 months to grow a ripe pineapple, so they are planted every day in Costa Rica to ensure continuous global availability—massive operations that, when combined with those ships and advanced “reefer” containers, only giant (obviously evil!) multinational corporations can pull off. Those same firms also use not only the usual fertilizers and insecticides but also special chemicals to encourage initial flowering and final fruit ripening. And they developed a new, more commercially appealing type of pineapple—first in Hawaii, then in Costa Rica—that helped fuel the rapid increase in U.S. pineapple sales in the 1990s and thereafter. As one outlet put it:

The introduction … of the MD‑2 or Sweet pineapple, with its low acidity and suitability for sea freight, allied with the power of a multinational in terms of production and marketing structure, marked the start of an exemplary success story which has radically changed the world market. Production began to grow rapidly from 1996, to meet the brilliant commercial success encountered both in the United States and in Europe, approaching one million tonnes in the early 2000s.

Grocery technology improved too for both pineapples and other fresh produce. For example, “controlled atmosphere storage,” which entails using low oxygen levels and high carbon dioxide levels in a storage atmosphere combined with refrigeration, prolongs storage and reduces damage or spoilage. And, of course, the computers, smartphones, and the internet surely provide even more areas for delivery, inventory, sales, marketing, and other improvements.

All in all, it’s a great example of how, as Grabow details at length, so much of modern globalization is driven by technology, profit-hungry innovators, and the good ol’ Invisible Hand—not tariffs or other top-down government plans or policies.

Call it “I, Pineapple.”

That’s not to say, however, that trade policies don’t also play a role here. As Bagley and I explain with respect to U.S. produce availability in general, free trade agreements have helped a good bit:

Much of the expansion in international trade in food is owed to trade agreements completed in the 1990s. In the United States, the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement improved Americans’ access to warm‐weather produce grown in Mexico and foods in which Canada specialized (and not just maple syrup). As a result, the volume of fresh vegetables imported into the United States, primarily from Mexico and Canada, has almost doubled since the late 1990s. Perhaps the best example is the avocado, about 90 percent of which ($3.1 billion annually) is imported—almost all from Mexico. Our southern neighbor also supplied more than half of all US berry imports (excluding strawberries) in 2022.

Globally, the 1995 World Trade Organization agreements, especially the Agreement on Agriculture, dramatically reduced global food and related trade barriers. Since then, agricultural trade has more than doubled in volume and calories. By 2019, countries were 50 percent more likely to form a direct global food trade link with another country than in 1995.

Some fresh pineapples come from Mexico and benefit from NAFTA/USMCA, and the GATT/WTO addressed some earlier liberalization. But for most of today’s pineapple imports, a different trade agreement is at play: the 2006 Central America-Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR), which includes Costa Rica and second-place Honduras and locked in 0 percent duty rates that these countries were already receiving under the narrower, time-limited Generalized System of Preferences for less developed countries (which we discussed in a previous column). For all other fresh pineapple imports, the U.S. applies a relatively low tariff that it has cemented via WTO Agreements.

The relative absence of government barriers to pineapple trade thus helps fuel today’s pineapple abundance.

As an aside, it’s important to note that the U.S. pineapple market was not always this open. Hawaii’s position in the industry, for example, has been repeatedly harmed by U.S. protectionism dating back to the 19th century. Before the Republic of Hawaii was annexed by the United States in 1898, numerous (canned) pineapple companies opened there to take advantage of the climate and relative proximity to the U.S. mainland. They quickly closed, however, because of “crushing” U.S. tariffs advocated by Florida pineapple growers. Those tariffs also killed, by the way, the Baltimore canning industry—a good example of how “upstream” U.S. protectionism hurts downstream U.S. manufacturing.

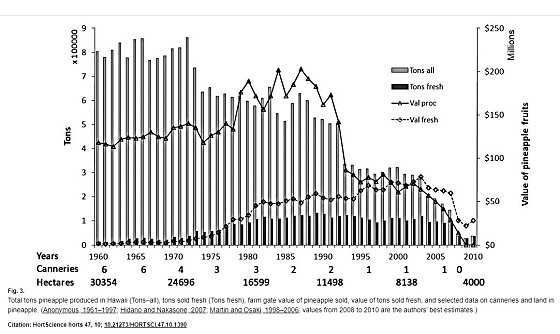

Once Hawaii became a state, pineapple companies could avoid the 35 percent tariff, and the industry took off, with Hawaii (Dole) supplying more than 80 percent of the world’s canned pineapple at its zenith. Hawaii’s industry is credited with producing the first commercially packed canned pineapple and notable contributions to global canning technology. After WWII, as Hawaii developed and Hawaiians got richer, however, the state began to lose market share to lower-cost countries like Thailand, Taiwan, and the Philippines. That led, predictably, to a 1973 petition for extra tariff protection from the International Longshore and Warehouse Union—and eventually to anti-dumping duties on canned pineapple from Thailand, which lasted until 2008 when the last petitioner, Maui Pineapple Company Ltd. went out of business (again, predictably). The case even went to the Supreme Court.

Even in 1973, however, it was clear that tariffs weren’t going to save the Hawaiian pineapple industry over the long term. As the U.S. Tariff Commission’s (now International Trade Commission) original investigation revealed, the primary factor driving up the cost of Hawaiian canned pineapple was unit labor costs, which constituted half of production expenses and had surged 90 percent from 1960 to 1972. Expensive land in increasingly touristy Hawaii was also a factor, and non-market forces also contributed to the industry’s demise.

In particular, the commission found that shipping costs from Hawaii to the mainland exceeded those from the much-farther-away Philippines and Thailand because of the Jones Act (which, as we know well, dramatically inflates shipping costs between the U.S. and Hawaii), and that Jones Act shippers had canceled regular shipping service between Hawaii and U.S. gulf and East Coast ports. Finally, the state of Hawaii imposed a specific tax on sales of pineapple land, which “the industry believes hampers the ability of pineapple to compete with other fruit produced in States that do not have such a tax and with imports of pineapple and other fruit.”

Some things never change.

Finally, the fresh pineapple story is—as with so much of globalization—a story about actual people. Beyond the ones selling and innovating are the people buying the product and craving even more. Thus, USDA has found, U.S. demand for pineapples is mainly responsible for the surge in imports and the related trade and technological advancements we have today. According to the agency, the growth of immigrant populations in the United States from tropical regions such as Latin America and Southeast Asia has played a significant role in increasing the demand for pineapple here—a great example, as Bagley and I also document in our essay, of how migration fuels food globalization.

Today, dishes featuring pineapples, like “salsa de piña picante” from Mexico, “pineapple lumps” from New Zealand (soft pineapple centers covered in chocolate), or the traditional Thai rice dish “khao pad sapparot” served in a carved-out pineapple help drive U.S. demand. Other factors, including the rising interest in fitness and well-being, do so too, as does pharmaceutical companies’ interest in the fruit’s possible medicinal benefits. Without Americans actually wanting this product, it wouldn’t be here in such quantities.

Summing It All Up

As Bagley and I detail, globalization expands our palates, fosters the sharing of diverse culinary traditions, enables year‐round access to fresh and healthy foods, and maybe even topples communism along the way. As the lowly pineapple shows, this isn’t magic; it’s the result of millions of people acting independently—innovating, trading, and (thankfully) eating—to better their (our) lives. We eat better than kings—a lot better—and all the government had to do was get out of the way.

Chart(s) of the Week

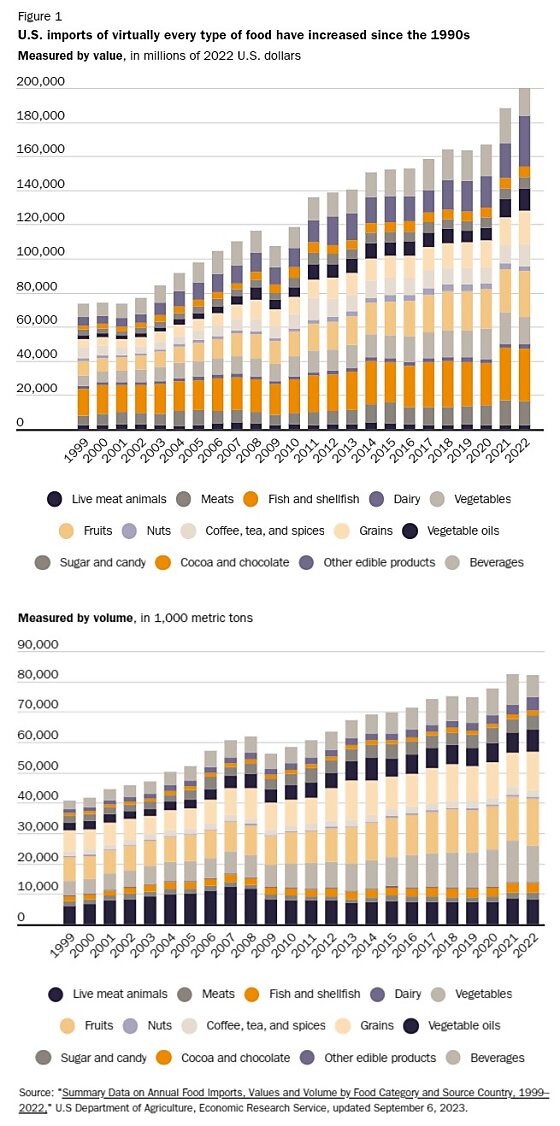

Adjusting for inflation, U.S. infrastructure spending is (still) way down: