When Nevada enacted the nation’s first nearly universal education savings accounts (ESAs), education reformers celebrated. ESAs empower families to tailor their children’s education to meet their individual learning needs and have the potential to unleash a wave of innovation.

Others, however, have been less enthusiastic. Perhaps the most common concern is the one raised recently by David Osborne, director of the project on Reinventing America’s Schools at the Progressive Policy Institute, who fears ESAs could exacerbate inequality:

[Nevada’s new ESA program will] make access to quality education less equal than it is today. Why do I say it will do that? Because it allows families to add to their education savings account to buy a more expensive education. Most parents want what’s best for their children, so those who can afford it will do just that. Those who can’t will not. And the education market will stratify by income, far more than it already does. In a decade, it will look like the markets for houses, cars and other private goods, with huge disparities based on wealth.

Osborne warns of vast inequality in education, but his doomsday scenario more appropriately describes the public education status quo.

Indeed, America’s public education system already looks like the market for housing because, to a great extent, it is the market for housing. Students are assigned to district schools based on the location of their home, so the quality of the local district school is a major consideration for those who can afford it. Educational choice laws like ESAs break the link between education and housing—and low-income families have the most to gain.

Breaking the Link Between Education and Housing

America’s district schools are already highly stratified by income. According to a 2012 report by the Brookings Institution, “the average low-income student attends a school that scores at the 42nd percentile on state exams, while the average middle/high-income student attends a school that scores at the 61st percentile on state exams.”

Wealthier families can afford homes in communities with better performing district schools. The Brookings report found that in “the 100 largest metropolitan areas, housing costs an average of 2.4 times as much, or nearly $11,000 more per year, near a high-scoring public school than near a low-scoring public school.” In other words, parents pay the equivalent of tuition at many private schools to live in districts with higher-performing public schools.

By empowering all parents to pay for education directly, ESAs and other educational choice programs cut housing out of the equation. Parents no longer have to be able to afford a house in an expensive community to afford the best educational environment for their children. In Nevada, the state will provide $5,100 in most ESAs and $5,700 for low-income families or students with special needs.

However, Osborne worries that the current level of ESA funding in Nevada won’t cover more than “a cut-rate job.” The average private school tuition, he notes, is between $8,000 and $10,000 while district schools spend about $8,300 per pupil annually on instruction (and more than $9,400 per pupil in total).

Nevada should do more to make funding more equitable, but $5,700 could still go a long way. For many families, it could make the difference between enrolling their child in a school that meets their needs or keeping them in a school that doesn’t. Moreover, looking at the average alone obscures the tuition that families actually face. As Glenn Cook of the Las Vegas Review-Journal explained recently, $5,700 is more than enough to cover the full tuition at several inner-city private schools and just shy of the posted tuition at several more—even before factoring in the schools’ tuition aid. The ESA might even encourage new high-quality, low-cost schools—like Acton Academies, which often charge as little as $4,000 in tuition—to enter the market.

Very soon, the Friedman Foundation will release a new report from its School Survey Series called Exploring Nevada’s Private Education Sector, which will shed more light on the issue of private school supply in Nevada. The report will not only include the number of open private school seats, but also the percentage of Nevada private schools that offer additional tuition assistance to low-income families.

Low-Income Families Benefit the Most

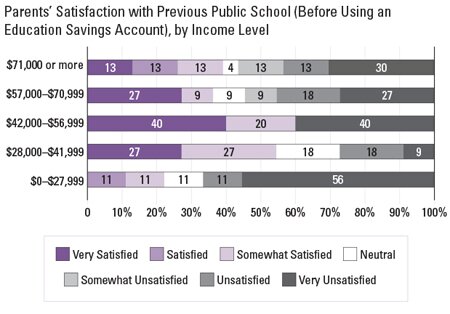

Research shows that low-income families have the most to gain from expanded choice. In 2013, Jonathan Butcher of the Goldwater Institute and I conducted a survey of Arizona families using ESAs in the first year of the program. Due to the program’s eligibility requirements at the time, all of the ESA families had students with special needs who had previously attended their assigned district schools. As shown in the table below, low-income families reported the highest levels of dissatisfaction with their district schools. Two-thirds of families in the lowest income quintile reported being dissatisfied, including 56 percent who were very dissatisfied while only 22 percent reported being satisfied or very satisfied.

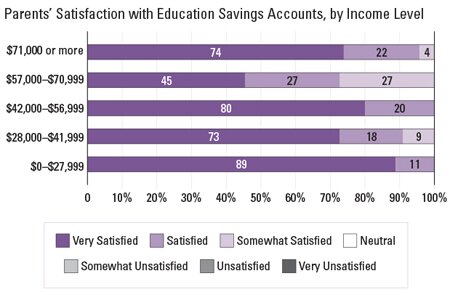

In stark contrast, survey respondents reported unanimous satisfaction with the ESA program. Moreover, families with the lowest income were the most enthusiastic with nearly nine in 10 reporting that they were very satisfied.

Osborne, however, is skeptical that the high degree of parental satisfaction is actually related to their kids getting a quality education:

[I]nformation about schools’ academic quality will be sparse, and many parents will be ill equipped to distinguish the wheat from the chaff. Experience in the charter school sector has proven that if a school is safe, warm and nurturing, many parents will stick with it, even if test scores show that students are falling behind. The same will be true in Nevada’s private schools, so many kids will get a lousy education.

Fortunately, numerous studies have explored the impact of choice programs on student outcomes. Eleven of 12 random-assignment studies—the gold standard of social science research—have found that school choice programs improve the outcomes of participating students, leading to higher test scores, higher rates of graduation, and higher rates of college enrollment. One study found no visible impact and none found any harm.

Moreover, parents have more access to information about schools than Osborne gives credit. For example, GreatSchools provides parents with ratings of private schools based on student performance data and reviews from parents. A recent American Enterprise Institute report found that parents give considerable weight to the experiences of other parents—and for good reason. As Matthew Ladner of the Foundation for Excellence in Education noted recently, parents are often tougher graders than state accountability systems.

Osborne also frets about the impact of school choice policies on the students “left” behind at their assigned district schools, but the research literature shows that they benefit as well. In 22 of 23 empirical studies, the academic performance of students who chose to stay in district schools improved as a result of the competitive effects of school choice. No study, even those conducted by anti-school choice organizations, has found private school choice programs harm the academic performance of students who remain in district schools.

Freedom and Equality

As Milton Friedman observed, “A society that puts equality before freedom will get neither. A society that puts freedom before equality will get a high degree of both.” Osborne himself argued that a “core value of public education…is equality of opportunity,” knowing full well that America’s current ZIP Code-assignment education system is highly stratified by income. Access to a quality education is too often determined by parents’ ability to afford a home in an expensive neighborhood. Without school choice options, the current system is not the bastion of equal opportunity it is often imagined to be.

If we want a high degree of equality, more states should consider following Friedman’s advice and focus efforts on expanding educational freedom and choice. Such policies empower families to choose what’s best for their kids without going through a real estate agent—and the best evidence shows that students are better off as a result. If more states adopted universal educational choice programs like Nevada’s, all children—especially low-income children—will benefit.