Wall Street Journal columnist James Mackintosh recently contemplated “How to Know When Inflation Is Here to Stay.” It concluded with advice to keep an eye on expectations about future inflation.

“Inflation expectations can become self-fulfilling,” writes Mackintosh, ” and are watched closely by the Fed. One-year consumer inflation expectations reached 4.6% in May, according to the University of Michigan survey, the highest since the China commodity boom of 2011.” On the other hand, he added, “the Treasury market’s long-term break-even inflation rate remains close to the Fed’s target of 2%. These, along with economists’ forecasts, should be watched closely.”

Another Journal columnist, Greg Ip, uses a similar consumer survey from the New York Fed which shows median expected inflation rising to 4% in May for the year ahead, with half expecting less and half more. In the New York Fed survey, intriguingly, taxes are expected to rise 4.7% — up from 2.8% before Biden took office. Taxes are indeed an ominous threat to the cost of living, but not something to be fixed by Fed tinkering.

“Three years from now, [New York Fed] survey respondents said they expected to see inflation at 3.6%, the second highest reading for the survey,” reports The Wall Street Journal. But the survey only dates to 2013, when respondents mistakenly expected 3.8% inflation three years ahead. Mr. Ip’s graph only dates to 2017.

The fundamental problem with inflation surveys is that they rise and fall each month with changes in current news about past inflation rather than being a leading indicator of future inflation. The Michigan expectations survey that Mackintosh referred to (4.6% this May) was also 5.2% in May 2008 and 4.1% in May 2011. But those fevers passed as quickly as the news changed. Inflation did not actually speed up after May 2008 or May 2011, as surveys expected.

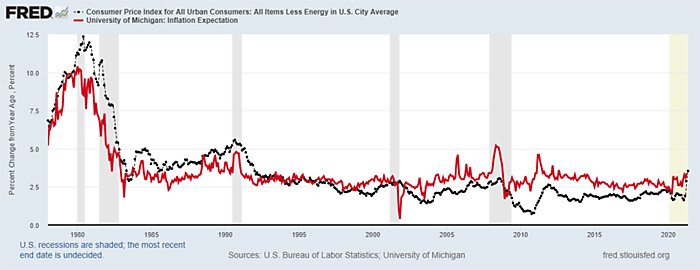

My first graph compares year-to-year trends in the consumer price index less energy with the monthly University of Michigan survey of expected inflation a year ahead. Energy prices are excluded because they play havoc with inflation reports, as will be explained soon.

With rare exceptions during recession years (shaded in the graph) University of Michigan survey expectations about inflation over the coming year follow what survey respondents could have easily known from news reports about what inflation had been over the previous eleven months.

At the time of this May’s survey, for example, it was widely known that the headline CPI was up 4.2% in April compared with the deeply deflated level of a year earlier. Unsurprisingly, consumers surveyed in May guessed inflation over the next year might look about like what the newspapers told them the previous year. That is what these polls always do. It is likely that year-to-year CPI inflation headlines will show smaller increases in June-August because the CPI was not falling in those months last year, unlike March-May. If so, surveys starting in July (because June surveys will mirror recent news about the May CPI) will discover that consumers expect less inflation starting in July.

When consumers tell pollsters about what they expect next year’s inflation news to look like, they clearly change the answers up or down depending on what the latest headlines show. Expectations follow the news, not the other way around.

James Mackintosh suggests “economists’ forecasts should be watched closely.” But basing policy on forecasts, including the Fed’s own forecasts, can be treacherous. Professional forecasters are notorious for regularly adjusting their forecasts to conform to the latest news. The contentious opinions of academic economists are even less helpful. A June 8 Chicago Booth survey asked 41 prominent academic economists if “The current combination of US fiscal and monetary policy poses a serious risk of prolonged higher inflation.” Only 11 of the 41 agreed that unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus might pose a serious risk at some point in the future, but another 11 disagreed. That left 17 uncertain and 5 others unwilling to hazard a guess.

The Fable of Self-Fulfilling Expectations

It is unusually hard to get a clear picture of actual inflation right now, much less of expected inflation. Consider what happened to world oil prices since the pandemic first struck. In April 2020 West Texas Intermediate crude oil was down 74.1% over 12 months, (at one point falling well below zero to settle at -$37.63 per barrel), which is just one pandemic-related reason year-to-year CPI inflation fell to zero that April and May. One year later, crude oil was up 128.1% from a year earlier. But that is obviously calculated from an extremely depressed base (-$37.63 on April 20, 2020).

Excluding energy prices helps minimize that pandemic distortion but there are hundreds of others. Apparel prices in cities were up 5.6% this May compared with a year ago, for example, but apparel prices fell 7.8% a year ago. To describe the increase in apparel prices since May 2020 as inflation is the equivalent of adopting last year’s economic collapse as the standard of normality.

The clearest way to look beyond such “base effect” distortions is to look at the changes in the consumer price index over 24 months rather than 12. The CPI less energy was 274.69 in May 2021, up 5.2% from 260.99 in May 2019. That is, the total increase in non-energy prices was 5.2% over the past two years, not one. And that means the annual rate of non-energy inflation was 2.6%.

Unlike consumer polls purporting to show expected inflation of 4% or more, a trend of 2.6% is consistent with the low expected inflation implied by 1.5% bond yields and by the 2.3% break-even rate between regular 10-year Treasury bonds and the inflation-protected variety (TIPS).

Why should we not spend more time examining such complex actual inflation statistics rather than pondering random samples of what ordinary Americans imagine the numbers might look like next year?

The trouble with poll-based estimates of 4–5% inflation is that such polls cannot predict actual inflation. Yet Federal Reserve poohbahs and their acolytes place great rhetorical importance on keeping inflation expectations “anchored.” The rationale for changing the subject from facts to opinion is that some otherwise fleeting disturbance might supposedly “push up public expectations of inflation, which tend to be self-fulfilling.”

The Self-Fulfilling Expectations Theory of Inflation (SFETI) claims workers who expect higher prices will “demand” higher wages. Why not always demand higher wages? Because it only works if you and your boss suspect you could earn more by quitting and working somewhere else. Such a tight job market would be a description of local facts, not national expectations.

SFETI theorists claim companies with higher expected inflation can profitably charge more for goods and services to cover any added labor or materials costs. But higher prices reduce sales. If any business is charging less than the price that would maximize profits, why wait for changing expectations about national inflation to charge whatever the market will bear? A seller’s market for any specific type of good depends on market-specific facts, not national opinions. And paying more for some things (used cars) leaves consumers with less income left over to spend on other things.

With higher inflation expectations and a thousand dollars you can spend exactly as much as with low expectations at a thousand dollars. You might spend it faster, but then you will end up with less to spend later so the early demand surge would peter out. You might borrow to spend more than you have, but then you will end up buying less rather than more because a chunk of your future income will go for interest payments to the bank.

A Self-Fulfilling Expectation Theory of Inflation is not logically compelling. At the least, it requires a real-world example. Greg Ip offers one. He claims that “Back in the 1970s, expectations were poorly anchored so oil shocks in 1973 and 1979 fed into broader inflation, forcing the Fed to raise interest rates sharply.”

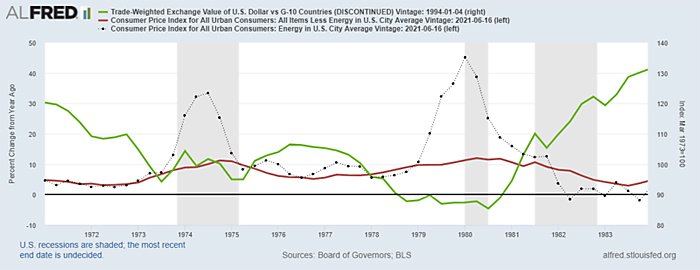

On the contrary, my second graph shows that the CPI excluding energy was accelerating long before crude oil prices spiked in January 1974 and again in 1979. Dollar prices of all internationally traded commodities — not just oil — rose sharply when the dollar fell by 15.9% against other G‑10 countries from 1971 to 1973 and later by 15.5% from 1977 to 1980.

The Inflation Expectations Theory cannot begin to predict or explain the ups and downs of inflation from 1971 to 1984. Deliberate deep devaluation of the dollar — first by President Nixon and later by Jimmy Carter’s Treasury Secretary Mike Blumenthal — fully explains why the whole world rationally expected more inflation in prices of things priced in dollars, including oil. Forgetting this sad history of dollar debasement, some young journalists now imagine that inflation is rising in weak-currency countries (Turkey and Russia) because of “a booming U.S. economy that is… pushing up the U.S. dollar.”

Market-Based Measures of Expected Inflation

Unlike consumers and economists polled about their opinions about future inflation, financial market participants have strong incentives to get the answer right. Inflation erodes the real value of bonds, making bond prices fall and yields rise. Yet the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds has been only about 1.43–1.53% lately, which is difficult to reconcile with headlines and opinion polls suggesting people expect sustained inflation above 4%.

Market expectations of the future are more plausibly estimated by the difference between the yield on regular (nominal yield) Treasury bonds and the negative yield on Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS). If the yield on 10-year Treasuries is 1.5% and the yield on 10-year TIPS is minus 0.9% (-0.9%), then the break-even rate would be 2.4%. That is called the “break-even rate” because holders of TIPS will eventually earn the same yield as owners of regular Treasury bonds of the same maturity if the inflation over those years turns out to be the same as the current break-even rate.

Since its beginning in 2003, the break-even rate has tracked changes in core inflation closely. To its credit, the break-even rate was not fooled by the ephemeral June 2008 $133 spike in crude oil, unlike consumer surveys. And it fell quickly and sharply when the economy contracted in early 2003 and 2009. St. Louis Fed economist Kevin Kliesen found the break-even rate has a much better track record than the University of Michigan opinions poll which typically overstates future inflation by a full percentage point.

The 10-year break-even rate declined from 2.54% on May 17 to 2.27% by June 17, and the 5‑year break-even rate fell from 2.72% to 2.31%. The best evidence we have tells us expected average inflation over the next 5–10 years is currently below 2.3%, and not rising.

As it turns out, the best gauge of expected inflation is a bit lower than the recent 2.6% annual rate of CPI inflation after we (1) use a two-year average to avoid being misled by the deeply deflated base prices last April-May, and (2) exclude the particularly extreme fall and rise of energy prices due to global Covid-19 lockdowns and reopening.

There might be higher inflation ahead, but neither year-to-year CPI changes, the 2020 lockdowns, or news-based monthly opinion polls about expected inflation provide reliable advance clues about what lies ahead. Meanwhile, the low break-even rate offers a good reason to be skeptical of high inflation forecasts.