After much delay, the U.S. Department of Labor last month issued a final rule on how it will determine whether a worker qualifies as an “employee” (as opposed to independent contractor) under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). We first discussed the preliminary DOL rule (and its fundamental problems) in late 2022, and a good rundown of the final regulation is here. In the interest of time (and my travel schedule), I won’t bore you with those details. Instead, today we’ll discuss why the rule remains costly, why it probably won’t achieve its primary objective, and how a new and important study on a similar regulation in California shows just these very things.

Will the Rule Work as Intended?

Various news outlets and partisans have couched the DOL rule change as a victory for workers forced or tricked into engaging in contract work. Now, so the theory goes, greedy employers will finally be forced to turn these poor contractors into traditional workers, with all the perks (wages/overtime, legal protections, benefits, etc.) that said employment supposedly provides.

The extent to which that shift actually happens, however, is far from clear.

For starters, most credible analyses of the DOL rule agree that, because it doesn’t really establish a bright-line rule for classifying a worker, it’ll take time and litigation before scholars and market participants understand the rule’s ultimate effects. There are already multiple legal challenges to the rule itself, and even if it does survive those challenges implementation will be bumpy. As Bloomberg put it a couple of weeks ago, most labor law experts agree that some (but not all or even most) independent workers will be reclassified under the rule. In other words, the rule’s precise scope and impact is very much TBD:

“One major impact of the rule’s going to be somewhat increased legal unpredictability, because the new rule is returning to an old test that’s open-ended,” said Timothy Taylor, a partner with Holland & Knight. “It has a lot of factors in it. It’s going to be harder to predict litigation outcomes. It’s going to be harder to predict who is an employee.”

Despite this uncertainty, most observers do still agree that the rule will probably affect millions of American workers in some way (recall that there are tens of millions of independent workers in the United States), and that smaller businesses—not large gig work companies like Uber—will likely feel it most.

Second, and regardless of the exact number of American workers affected by the final rule, there is no guarantee that they’ll actually benefit as the rule’s supporters contend. In fact, new research strongly suggests that they won’t.

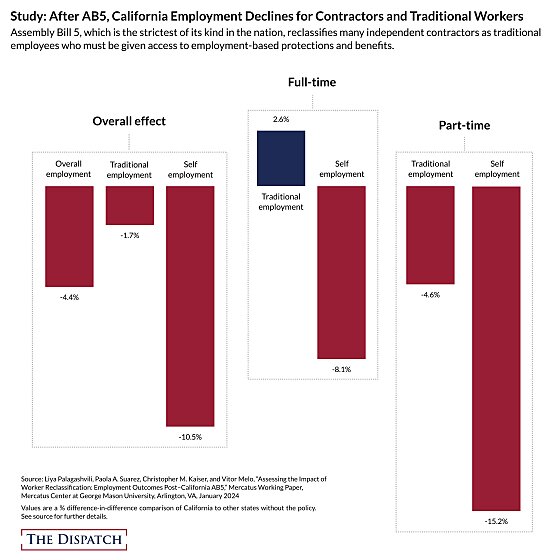

In a new and novel working paper for George Mason University’s Mercatus Center, authors Liya Palagashvili, Paola Suarez, Christopher M. Kaiser, and Vitor Melo examined what happened in California’s labor market after the state government enacted Assembly Bill 5—a stricter version of the DOL rule that was implemented in 2019 and forcibly reclassified many independent workers in the state as traditional employees (see my previous column for more). By comparing the employment outcomes of AB5-covered occupations in California to the outcomes for those same occupations outside of California, they make three important findings:

- First, self-employment and overall employment for covered occupations significantly decreased after AB5 entered into force. On average, self-employment in these occupations fell by 10.5 percent, while overall employment fell by 4.4 percent. Results varied for full-time and part-time workers, with the former seeing self-employment drop by 8.1 percent and no real change to traditional employment. Part time workers, on the other hand, saw a 15.2 percent and 4.6 percent drop in traditional and self-employment, respectively.

- Second, and quite logically, the authors found greater declines in both self-employment and employment in occupations that tended to have more self-employed workers prior to AB5 (e.g., farmers and ranchers, chiropractors, and repairmen). For these occupations, self-employment fell by a whopping 28 percent and overall employment fell by as much as 14 percent.

- Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there was no strong evidence that traditional (W‑2) employment increased after AB5 took effect—the result lawmakers and other AB5 supporters intended (or, at least, say they intended). That null result wasn’t uniform across all occupations, of course, but even “in cases where we see an increase in W‑2 employment, this increase was not large enough to offset the significant decreases in self-employment, thereby resulting in an overall reduction of employment in California.”

Just to be clear, the Mercatus paper doesn’t confirm that AB5 caused these results—just that they occurred after AB5 took effect and were unique to California. Still, the authors convincingly show that AB5 didn’t produce the results supporters claimed it would (i.e., keeping overall employment steady and simply shifting covered workers into traditional employment from their previous independent contractor status). Instead, occupations covered by AB5 saw a significant decline in self-employment (expected) and a significant decline in overall employment (surprise!).

The authors then conclude by noting the obvious implications that their AB5 results have for the new DOL rule:

The justification and intention of the [DOL] rule is to merely alter the composition of the workforce—more workers would become employees (with access to labor protections and benefits) and fewer workers would be independent contractors. Our analysis herein would suggest that the DOL may have challenges in meeting these intended results. Instead, we may expect the rule to be associated with a decrease in self-employment nationwide, and it is not clear whether it would definitively lead to an increase in traditional employment. Even if the DOL rule would lead to an increase in traditional employment, our results suggest that the increase in traditional employment will likely not be greater than the reduction in self-employment, thereby leading to a decrease in overall employment. Although the DOL rule is not as stringent as AB5, its rule cannot exempt any industries, occupations, or professions as AB5 did, and, therefore, the effect of the rule is expected to be more widespread.

Put simply, if the DOL rule follows AB5’s lead, we should expect not merely fewer contractors but less U.S. employment overall.

Putting Square Labor Pegs Into Round Real-World Holes

So why might this be the case?

The fundamental mistake that supporters of these types of labor regulations make is that they assume a binary world in which one less gig/independent worker automatically means one more traditional worker. That’s just not how things often work in the real world for both employers and employees.

For employers, if the government raises a worker’s cost (money, benefits, time, paperwork, legal liability, etc.) above the value that the boss thinks the worker can actually produce for the firm, the employer may simply choose to not hire the worker at all. In some cases, businesses might just shut down altogether if they can’t make the new numbers work. And because large employers often have the flexibility and resources to maneuver around these additional costs (including by increasing hiring in other states or even other countries), it’s the smaller, more local firms that’ll likely feel these effects most—something, as noted above, most experts expect with the new DOL rule.

For employees, meanwhile, we discussed in 2022 that tens of millions of Americans don’t actually want to be traditional employees and/or really like independent work arrangements. I provided oodles of data from my book showing this very thing, and subsequent surveys show much the same (if not even stronger support). For example, the latest “State of Independence” Report (2023) from contractor support firm MBO Partners finds that a whopping 72.1 million Americans, mainly side-hustlers (36.6 million) and full-timers (26 million) engaged in independent work last year, up significantly since 2020. Of those independent workers:

- 63 percent work independently by choice, while only 9 percent are contractors because of factors out of their control (e.g., job loss or not being able to find a job).

- 78 percent plan to keep working independently in the coming months, while only 12 percent are angling to do something else (traditional work, retire, etc.).

- 40 percent are caregivers for a family member, and independent workers frequently cite these caregiving responsibilities as what’s driving their independent work status.

- 77 percent are “very satisfied” with independent work, a share that’s been steady since 2019 (i.e., through U.S. labor market highs, lows, and other big changes).

- Only 29 percent said job security was a “challenge,” while 66 percent actually see independent work as “more secure” than traditional work.

- A majority (53 percent) of full-time contractors say they earn more than they could at traditional jobs, and 4.6 million of them made more than $100,000 in 2023.

A similar survey from freelance platform Upwork finds similar enthusiasm for contract work and further emphasizes that many freelancers aren’t the low-skilled gig workers we so often hear about. In fact, 51 percent of freelancers performed “knowledge work” in 2022, while only 37 percent provided less skilled services. About half, moreover, had either a bachelor’s degree (23 percent) or postgraduate degree (26 percent).

As we discussed last time, the big driver of the modern independent work movement isn’t nefarious capitalists or a terrible U.S. labor market. Rather, it’s Americans’ increasing desire for flexibility and lifestyle over the possible benefits that traditional work can provide (security, benefits, legal protections, etc.) That so many workers, including those with plenty of education and skills, are choosing this path in a time of historic labor market tightness – with job openings still elevated well beyond historical norms – is a strong testament to that preference.

And the data and anecdotes again reinforce this conclusion. According to the new MBO study, for example, 70 percent of surveyed independent workers said “doing something I like is more important than making the most money,” while a different 70 percent said “flexibility is more important than making the most money.”

Scroll through the headlines and you see similar preferences across industries:

- Wall Street Journal (October 2023): “Logistics operators are giving workers more flexibility as competition for labor from Uber, Instacart and other app-driven companies heats up”

- Bloomberg (July 2023): “Most manufacturing assembly lines are still built around employees working at least eight-hour shifts, five days a week, and that’s been a hurdle for industrial companies competing for talent in a labor force that increasingly prioritizes flexibility.”

- Wall Street Journal (January 2023): “More than half of respondents overall said they would take a pay cut for more work-life balance or to have more flexibility in how they structure hours.”

- Wired (December 2022): “Forget return-to-office mandates. The most sought-after talent want ultimate flexibility. Their bosses need to get on board.”

As anyone who follows me on Twitter knows, there are plenty more where these stories came from. No, not every American worker or employer has such preferences, but millions and millions do. And having a diverse, open, and fluid labor U.S. market lets competent adults work the details out for themselves, with big benefits for both them and the U.S. economy overall. Yes, there are and will continue to be isolated instances of abuse of such an open system. But to the extent a government solution is needed in those cases—a questionable assumption in a time of high labor demand—that fix should be local and narrow, not the saturation bombing campaign unleashed by the AB5 and similar regulations.

As California shows, a highly regulated, one-size-fits-some U.S. labor market won’t produce a utopian ideal for all 167 million American workers. Instead, it’ll exclude many of them from the market entirely.