Dear Capitolisters,

On the list of Washington priorities right now, the need to do something about China is at or near the top, and therefore motivates a lot of policy proposals—often seeded by lobbyists or special interest groups—that politicians might otherwise oppose. For example, we see supposed free marketers supporting protectionism and industrial policy not because they’ve seen the interventionist light but because the China’s growing economic and geopolitical power—both supposedly fueled by Chinese government industrial policy—is so serious that it demands we abandon, just this one time, the market to save it (or something), or that we accept dozens of ridiculous, irrelevant, and/or self-serving amendments to “innovation” legislation because it’s the lone legislative vehicle for Congress to do something about China this year. (Both were on full display in last week’s newsletter.)

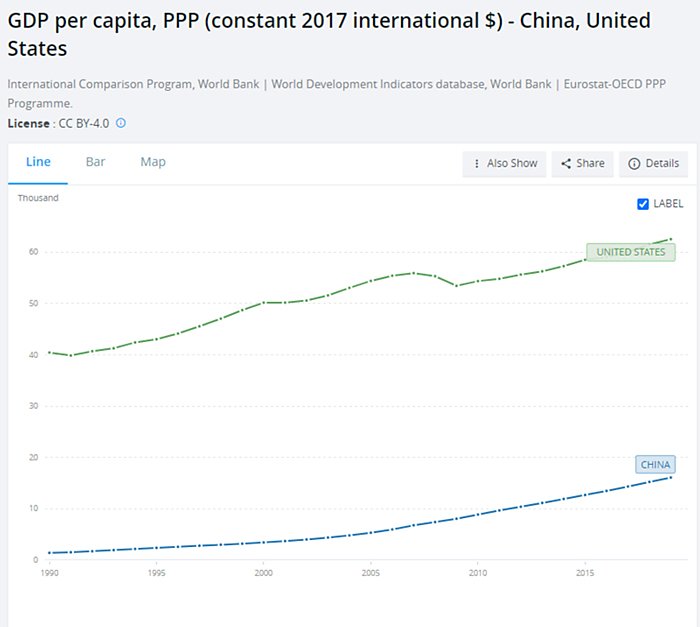

Surely, some of Washington’s newfound attention toward China is warranted. Its economy has expanded rapidly since the late 1970s, as has its share of global economic output and trade. China is today the world’s largest manufacturing nation, with growing high-tech and internet industries, and many nations’ largest trading partner. Its massive population (about 1.4 billion people, many of whom are just entering the global consumer class) also gives it economic heft beyond its per capita numbers, which are still well below the United States and many other Western nations.

And then, of course, there’s China’s recent and troubling embrace of illiberalism and expansionism, coupled with a “wolf warrior” diplomacy that is sure to aggravate existing tensions and produce new ones—especially when Western companies and individuals embarrass themselves in trying to satisfy the Communist Party’s demands.

However, while China’s deepening authoritarianism, human rights abuses, and other bad behavior surely warrant criticism and attention, the view of China, and Chinese industrial policy, as an urgent economic threat to the United States—one justifying a broad rejection of the free markets and economic openness that made America great to begin with—is mostly misguided. And since it motivates so much of what goes on in Washington, it’s what we’ll dig into today.

What Fueled China’s Rise?

China’s economic rise is undeniable and has caused many to assert that the country—fueled by its “state capitalism” model—will surpass the United States as the global economic hegemon in the next few decades. This speculation, however, suffers from two critical errors. First, “state capitalism” didn’t drive most of China’s past economic out-performance. Instead, those gains came primarily from market-based reforms that China started in 1978 (from a very low, communism-induced baseline) and continued via its integration into the multilateral trading system—i.e., the World Trade Organization—in 2001 and the requisite structural and economic changes that said accession required. For example, a 2012 study by University of Toronto economist Xiaodong Zhu concluded that China’s growth was “driven by productivity growth rather than by capital investment,” thanks to “gradual and persistent institutional change and policy reforms that have reduced distortions and improved economic incentives.” (See also this IMF study.) As I wrote last year, moreover, many other economists have found that most of China’s improved export competitiveness stemmed from internal, freer market reforms—on property rights, privatization, price controls, trading rights, and import liberalization, for example—often in response to new WTO commitments.

China’s past economic growth is also notable in what it didn’t feature: lots of industrial policy. As China expert Barry Naughton explained in his great new book, The Rise of China’s Industrial Policy:

[T]here is a huge disconnect between the success that we attribute to the Chinese economy today and the orientation of Chinese policy today. China’s emergence as an economic and technological super-power is due primarily to the policy package that it followed from 1978 through the first decade of the 21st century, that is, until about 2006–7. China’s policy package today—that is, the policies that started tentatively after 2005 but were fully in place by 2008–2010— are radically different. Because of this, it is a mistake to attribute China’s success to the policies China is currently following.

By contrast, Naughton agreed with the aforementioned economists—and many others—that the “driving force of industrial development” in China was “market-oriented economic reform,” with the government primarily relying on market forces and minimizing direct interventions. Economic success was particularly tied to China’s WTO entry (see my 2020 paper for more). “How much of that success could be attributed to industrial policy and planning?” Naughton asks, “The answer is simple: none.”

As Naughton notes, the Chinese industrial policies that American critics today target began in 2006 but really intensified in size and scope after the 2008 global financial crisis. (Many China-watchers believe that the GFC caused a sea-change in Chinese economic thought regarding the weakness and instability of western-style capitalism.) Today, Chinese industrial policy covers a wide range of government actions but prioritizes high technology and advanced manufacturing industries via tens of billions of dollars in direct and indirect government support.

Has Chinese Industrial Policy Worked?

The mere presence of government billions and past economic success, however, do not guarantee future success—thus, the second critical flaw in the China Threat thesis: assuming that they do.

Surely, China has had some industrial policy successes, particularly in its energy sector, but it’s had plenty of failures too. Most notably, China has spent decades and countless billions of dollars trying to become a global leader in semiconductor production, but its domestic players are still, by most expert accounts, years (if not decades) behind the world’s best producers and totally reliant on the United States and other countries for top-end chipmaking equipment. China’s industry has also suffered from numerous, high-profile failures and bankruptcies, and China’s national champion, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), is developing facilities to produce chips that “are five to six years behind the industry’s leading edge at 10 percent of the volume of the world’s leading firm.”

Industrial policy likely shoulders much of the blame for the current state of the Chinese semiconductor industry, which features rampant misallocation of resources, ineffective implementation, corruption, and a significant shortage of human capital, as well as heavy reliance on well-funded but uncompetitive state-owned enterprises (SOEs). China will keep trying, of course, but future success is far from certain. As Christopher Thomas from the Brookings Institution explained, “most segments of China’s semiconductor industry remain behind its foreign competitors, and its efforts to catch up face major economic obstacles.” (It would be good, however, if U.S. immigration restrictions stopped helping the Chinese industry solve its human capital problems!)

Even where Chinese industrial policy has developed a competitive industry, its efforts in electric vehicles (EVs) show that the costs can be astronomical, successes modest, and future, market-based growth uncertain. Chinese EV subsidies, started in 2009, did support substantial growth in its domestic industry, but they cost nearly $60 billion between 2009 and 2017 and “sprouted a litany of problems that made Beijing worried that it was replicating the mistakes in the traditional auto industry” (which had its own longstanding share of Chinese industrial policy struggles):

Instances of fraud and collusion were made public by a 2016 government investigation. In several instances, manufacturers received subsidies for vehicles that existed only on paper or that were equipped with batteries that didn’t meet subsidy eligibility requirements. In some cases, vehicles were sold to companies related to the manufacturer so they could pocket the subsidies. …

The cost of subsidies may have been worthwhile if the irrational exuberance that accompanied this “let 100 EV firms bloom” period also led the way in technological superiority. Yet even as registered EV firms mushroomed to more than 400 by 2018, according to some estimates, only about 15% of them are actually manufacturing cars. The vast majority of these firms appears to have either not reached the production stage or have products of questionable quality.

The Chinese government quickly curtailed EV subsidies in 2019, but that caused EV sales to drop substantially—causing some to question whether the market was viable without all those subsidies. China also may have failed to produce a high quality EV “champion,” as Chinese companies still lag behind the world’s leaders and Tesla is venerated there.

Similar Chinese industrial policy “successes” can be found in the shipbuilding, civil aircraft, and, as noted, automotive manufacturing industries. (Embarrassing headline in The Economist just last year: “China has never mastered internal-combustion engines.” Yikes.)

And these are just the direct costs. China’s industrial policies have also been shown to indirectly foment numerous problems proven to hinder stable, long-term economic growth, including resource misallocation; corruption; investment bubbles; and overcapacity. Some may argue that these costs and distortions will eventually be worth it if supported Chinese industries someday thrive, but this ignores what may have been if China had pursued freer markets to begin with. At the very least, these struggles and their massive costs should at least give us pause before trying to copy China’s industrial policy system (assuming we even could).

Then There Are the Systemic Issues

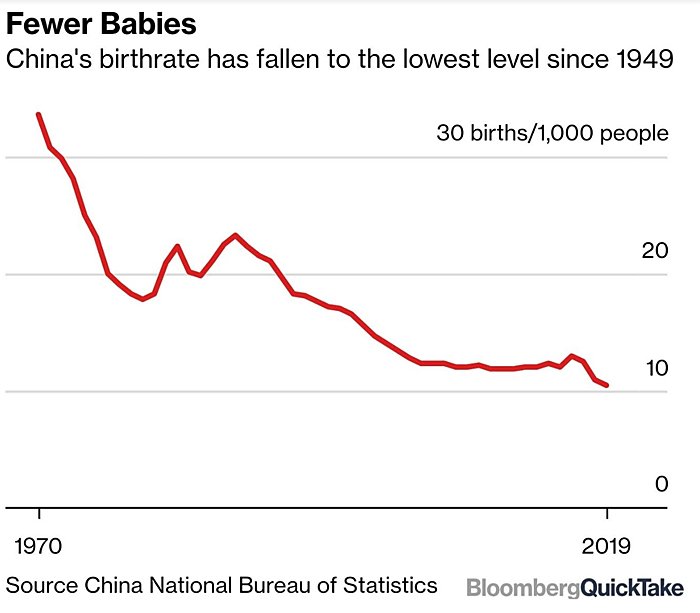

Finally, China faces broader, systemic challenges that call into question whether it will stay on the same economic trajectory for decades to come (a classic mistake in economic forecasting). For starters, China has major demographic headwinds that will only accelerate in the coming years. Despite relaxing its repressive and decades-long family planning policy, China’s birth rate continues to fall, and its population last year rose only to 1.41 billion from 1.40 billion in 2019, with individuals older than 60 now accounting for almost one-fifth of the population.

An aging China creates pressures on domestic consumption, labor force participation, pension and health care systems, and overall economic growth. As one demography expert put it to the New York Times, “This is a long-term time bomb.”

China could offset demographic concerns with rising productivity (the government is apparently uninterested in immigration), but this factor is also lagging—in part because of Chinese economic planning and industrial policy. According to a new International Monetary Fund Report, China’s average productivity rate is only a third of that in advanced economies—including Japan, Germany, and the United States:

This is not a new problem: According to a 2014 study, for example, Chinese Global 500 firms grew from three in 1995 to 89 in 2013, but compared unfavorably to their Western counterparts, with larger payrolls, less capital intensity (assets divided by number of employees), lower profitability, and less innovation.

It’s also an open question as to whether China will ever catch more productive economies like the United States. Productivity growth has stagnated in recent years, with average annual growth dropping from 3.5 percent between 2007 and 2012 to only 0.6 percent from 2012 to 2017. As noted by The Economist last year, growth in total factor productivity is now only a third of what it was before the Great Recession, a much sharper decline than other countries and just as China was spending billions to create a global semiconductor leader:

Indeed, the Wall Street Journal explains that much of China’s productivity slowdown is attributable to the government’s “massive stimulus program to prop up economic growth” after the global financial crisis and has further deteriorated as industrial planning ramped up under President Xi Jinping. Other drags on productivity include recent government efforts to control private businesses and growing bureaucratization, which has confounded central government efforts to implement economic and social reforms that might boost national productivity.

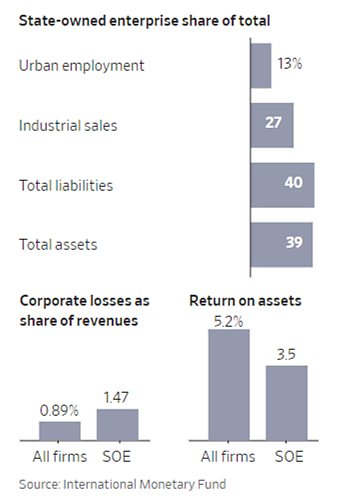

Inefficient state-owned enterprises are also a significant cause of China’s productivity issues, as the Journal (citing the above IMF report) notes:

Despite constituting a smaller share of China’s economy today as compared to decades ago, “SOEs are dominant in key industries, including energy, aviation, finance, telecoms and transportation” and remain favored by government policy. Yet their productivity lags far behind privately owned counterparts, as does their innovation: “as judged by the numbers of patents granted for every unit of investment in R&D, private companies in China are three times more efficient than are state-owned enterprises.” Unfortunately, Chinese SOEs’ economic prominence appears to be growing, with the government increasingly favoring these entities while cracking down on private firms and entrepreneurs, especially in the tech sector.

Finally, China faces a growing debt burden that will, unless tamed, weigh on future growth. China’s debt-to-GDP ratio reached approximately 280 percent in 2020 (295 percent if foreign debt is included), the majority of which is in the form of corporate bank loans.

However, China’s banks—long considered tools of Chinese industrial policy (via, for example, low-interest loans to preferred industries)—are showing signs of strain. In 2020, Chinese banks had a record high of $466.9 billion in non-performing assets—a number that is expected to continue rising in the future. According to the Bank of Finland (BOFIT), moreover, “China was already engaged in efforts to bail out small and medium-sized banks before covid-19 struck,” and stress tests released by People’s Bank of China in November showed that 10 of 30 banks—including all of China’s “systemically critical banks” would fail “even under the mildest stress scenario.” Corporate bond markets are also strained.

Chinese government debt is today probably manageable (approximately 70 percent of GDP), but is expected to expand significantly in the coming years as the government funds a social safety net for its aging population. (Certain Chinese industrial policy projects, such as high-speed rail, also contribute to China’s growing public debt burden.) As the BOFIT analysis put it, “China’s piling on of debt has long raised concerns among observers of the Chinese economy because rapid descents into indebtedness in other countries have typically led to major economic collapse or severe banking crises.” While a crisis seems unlikely in the near term, such concerns are almost certain to weigh on future growth and other government initiatives.

Summing It All Up

Combined, these facts rebut the all-too-common perception in the United States that China is an unstoppable economic juggernaut that—fueled by industrial policy and heavy state planning—will inevitably overtake the United States unless we adopt similar policies here. It all harkens back to a similar bout of pessimism the last time the United States was allegedly destined to be overtaken by an upstart Asian nation:

my thanks to everyone who recommended other 1980s & 1990s Japan-bashing books & #industrialpolicy apocalyptic volumes. I’ve started building a slide depicting them all together. Feel free to suggest others I can add. It’s worth documenting this history before we repeat it. pic.twitter.com/ciQgVEG8U3

— Adam Thierer (@AdamThierer) June 1, 2021

Surely, there are differences between Japan then and China now, but there are also many similarities—especially in Washington. Indeed, many of the same folks preaching American decline today did so 30 years ago too. It’s more disappointing, however, to see such talk from Republicans who—so they say—believe in American exceptionalism and our free market system.

And, sure, it’s possible that China can overcome the above economic headwinds and several others (for example, environmental degradation, overseas project failures, restive populations, alienation of foreign firms, and increasing illiberalism)—it’s undeniably a large economy with a huge and increasingly educated population. But China’s economic challenges, caused in no small part by its relatively recent embrace of illiberalism and interventionism, are quite real, and they argue strongly against radical changes to U.S. economic policy as a last-ditch effort to counter an inevitable global hegemon.

Those changes should be considered on the merits, not out of an overwrought fear of the “China Threat.”

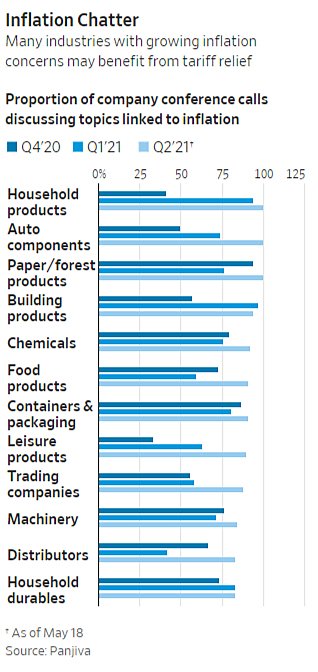

Chart of the Week

(source)

Bonus Chart of the Week

The Links

Cato’s hiring a trade economist

“Why shareholder capitalism benefits wider society”

More protectionist nonsense added to the Endless Frontier Act

Still a lot of people collecting supplemental unemployment benefits

It’s salad days for teen workers

The CDC has really botched outdoor mask guidance

U.K. “industrial policy failure”

Once a dying textile town, Greenville, S.C., is booming

Massachusetts banned surge pricing, and you’ll never guess what happened next

Teslas made and sold in Texas may have to be shipped out of state and shipped back to customers

New study on the politicization of American Rescue Plan funds

Companies offering prizes for vaccinated customers (more) (more) (more)

Lumber coming in from Europe is clogging a Florida port

Jason Furman on economists’ quiet criticism of the American Rescue Plan