Dear Capitolisters,

Among the handful of topics on which folks on the left and the right seem to agree is that large chain restaurants and “big box” stores are Bad, while small, local establishments are Good. Various polls reveal this preference (as does a lot of online snark), and politicians at all levels of government routinely push policies to aid “small businesses” or directly punish the big ones. Chief among the reasons for this preference is the widely accepted notion that small, independent businesses are manifestly good for local communities, boosting not just jobs and tax revenue but also a town’s identity, cohesion, and social capital. Chains, on the other hand, are American consumerism at its worst, basically doing the opposite of the great stuff that local shops do.

As I wrote a couple years ago, the economic arguments against big box retail are weak—they pay relatively well (better than mom-and-pop competitors), boost local economic output, and are great for consumers. But that’s just heartless libertarian talk; maybe those communitarian arguments against big chains are important—important enough, in fact, to pay the cold, calculating economic costs of supporting them?

Well, that doesn’t appear to be the case either—at least when it comes to encouraging social interactions among America’s rich, poor, and middle class. In fact, according to a fascinating new working paper, the establishments that do the most in this regard aren’t your local boutiques or gastropubs—or even our libraries and churches—but Applebee’s and other chains like it.

No, really.

We’re All in the Chain Gang, Apparently

In “Rubbing Shoulders: Class Segregation in Daily Activities,” economist Maxim Massenkoff and sociologist Nathan Wilmers use a mountain of anonymous cell-phone location data to determine where people live (a good predictor of their socioeconomic status) and visit each day. They then use those data to measure “exposure”: the chance someone from a certain neighborhood (and thus socioeconomic class) has an encounter—being in the same place at the same time—as someone else in the same or different socioeconomic group. For each establishment in the United States, they then calculate the share of visitors from each socioeconomic groups (broken down by income quintile), thus revealing “the extent of income segregation within the millions of places that people shop, work, relax, access government services, and socialize outside of the home.”

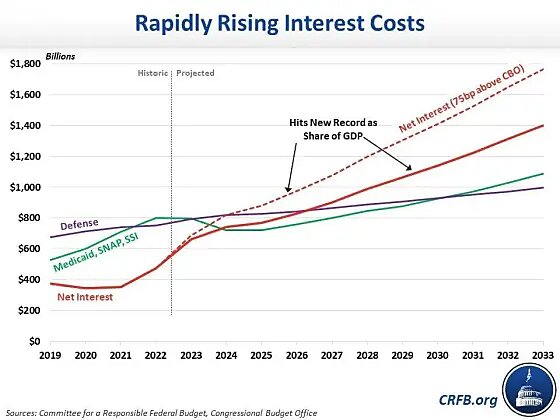

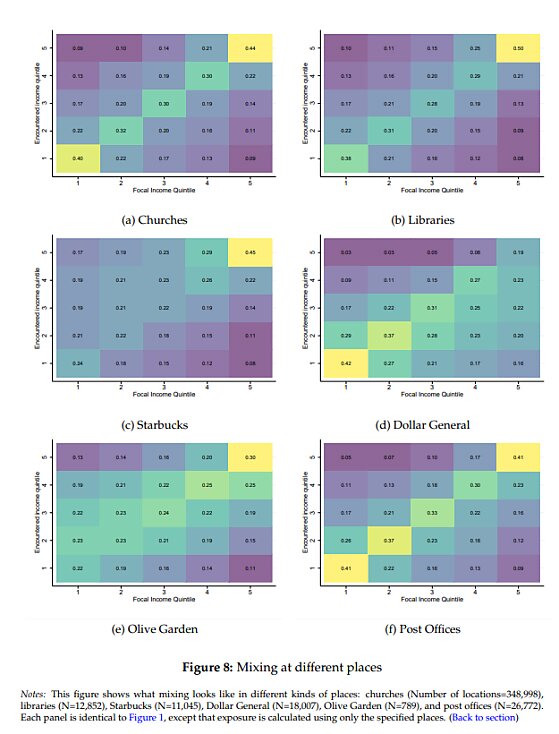

Some of their findings are intuitive and unsurprising. As illustrated in the following chart, for example, the researchers confirmed that people in high-income neighborhoods (number 5 on both the X and Y axis) really do live in a bubble: They’re more isolated than any other group, having 41 percent of their encounters occur with other residents of high-income neighborhoods (about 60 percent more isolated than any other income group). Low-income residents (number 1) are also isolated—but not as much as the rich. And these two groups don’t mix much—about 10 percent of their encounters (the deep purple boxes where 1s and 5s intersect) are with people from the opposite neighborhood. The other income groups mix most with their group too, but just by a smidge. Thus, they’re far less economically isolated than America’s rich and poor.

This chart also shows two “subtly different” types of isolation and social mixing that the authors study: “rich to non-rich” (column 5) and “poor to non-poor” (column 1). They provide a simple example of why this distinction matters: “If a high-income resident visits a store that is otherwise composed entirely of poor visitors, that visit will increase the high-income resident’s exposure to the poor. However, if a poor person visited that same store, it would increase her isolation, as, notwithstanding that single high-income visitor, all of the other visitors are poor.” Thus, they average the two figures to determine establishments’ overall mixing/isolation effects from both the high- and low-income perspective.

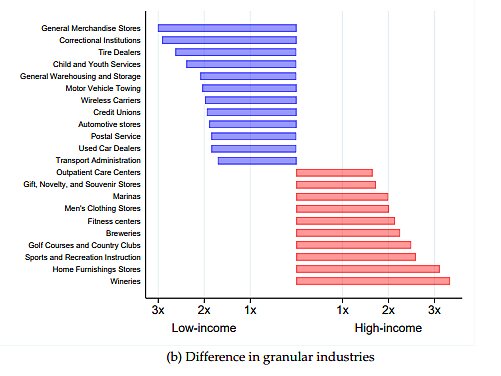

The authors’ analysis of which specific industries are the most/least segregated is also mostly unsurprising (and sorta funny): As shown in the following chart, rich Americans are far more likely than poor Americans to visit places like wineries and golf courses, while poor Americans are more likely to visit correctional institutions, credit unions, and general merchandise stores like Dollar General. (Shocking results, I know.)

They go on to find, however, that for the most frequented establishments, it’s not really the type of industry that drives segregation, because “people segregate across stores in a way that reproduces class divisions.” In other words, wealthy people and poor people go to a lot of the same types of places (e.g., drug stores), but they go to different locations and, in so doing, end up crossing paths with mostly people of their same income group.

Two other factors, by contrast, are big drivers of socioeconomic isolation. First and most important is geography: We mostly visit places near where we live (80 percent of all visits are within 10 miles of home), and U.S. neighborhoods are socioeconomically segregated. Thus, for both rich and poor, “isolation is highest close to home.” They find that this factor alone explains about one-third of rich/poor isolation, and it’s crucial to some of their most surprising findings. The second big driver is brand identity, but only for the rich. Everyone else is more egalitarian about where they shop (snobbery is real!). Thus, they find that, “Brand and distance go a long way toward explaining the isolation of the rich,” while it’s mostly about geography for the poor.

Finally, we get to where things are most surprising—the types of establishments that increase socioeconomic mixing.

- Massenkoff and Wilmers find that places we normally think of as “communitarian”—e.g., churches, libraries, the post office, etc.—actually tend to have higher levels of socioeconomic stratification, mainly because of the aforementioned geography driver. So, when wealthy Americans go to these places, they encounter people from the bottom two income quintiles only about 20 percent of the time, and it’s basically the same situation for folks in the bottom-quintile of incomes encountering wealthier cohorts. Supermarkets and schools tend to do the same, again owing mainly to residential segregation.

- Places like Starbucks and Dollar General have high levels of isolation for only the income group to which they cater most. The rich concentrate at Starbucks, so poorer people will meet more rich people when they go there (but rich folks won’t mix with many poor people). It’s vice versa for Dollar General, while gyms have a similar “Starbucks effect.”

- Meanwhile, the most egalitarian of places, where mixing increases for both rich and poor (and thus on average) is—wait for it—Olive Garden, which lowers levels of isolation almost across the board, as does much of the restaurant industry as a whole.

Much of this is shown in the following charts:

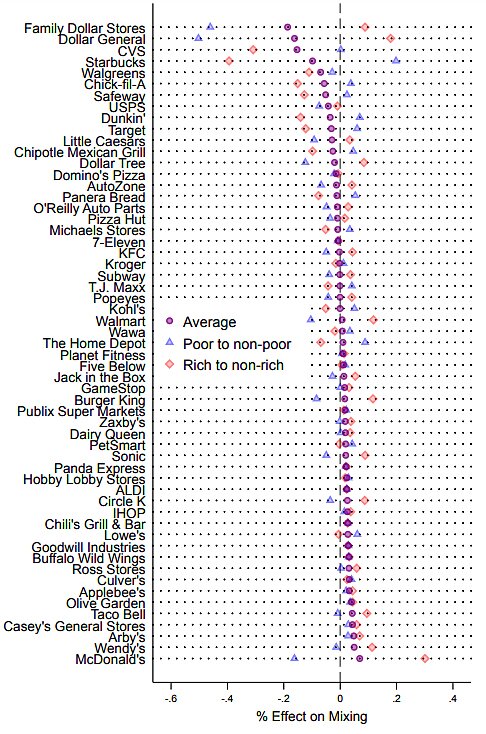

The authors reinforce these conclusions with a deeper dive into specific establishments, ranking them by overall isolation in the next chart (with the top being most isolated and bottom being the least), while also detailing how socioeconomic mixing occurs at these places—poor people mixing with non-poor (blue triangle) or rich with non-rich (red diamond):

This review produces the following insights:

- Cheap chains like Family Dollar and Dollar General can reduce mixing by isolating the poor. Starbucks essentially does the same for rich people.

- Chains with lots of local, neighborhood branches, like Walgreens and CVS, also reduce mixing, but because of geography (neighborhood segregation) effects. Put simply, there are so many of these places that we don’t leave our segregated home neighborhoods to visit them.

- Many big fast-food chains—McDonald’s, Wendy’s, Burger King, Sonic—increase mixing. However, they do this mainly by exposing rich people to the non-rich people who frequent these places, and can actually exacerbate the isolation of the poor for the same reason. There are, however, a few notable outliers here: Chipotle and Panera actually increase average isolation, primarily by the rich, while Arby’s and Zaxby’s increase both types of mixing.

- Once again, the genre of chains that consistently increases socioeconomic mixing among both rich and poor is full-service, low-price restaurants like Olive Garden, Applebee’s, Chili’s and IHOP. Also scoring pretty well in this regard are Lowe’s, the home improvement center, and Ross, the discount retailer. These places, it seems, hit the sweet spot for socioeconomic intermingling: desirable and common enough to attract people of all types, but not so ubiquitous as to keep us all in our own, distinct neighborhoods.

Finally, the authors look at what places disproportionately cater to a city’s lower-income residents, without regard to mixing with other groups. Here, they find that churches, libraries, parks, and big chains (those with more than 500 nationwide locations) score well, while museums and independent (non-chain) stores don’t. Chains are also more racially diverse than non-chains—again, likely due to neighborhood effects.

Based on these findings, the authors conclude that, “The places that contribute most to mixing by economic class”—for rich, poor, and in-between—“are not civic spaces like churches or schools, but large, affordable chain restaurants and stores.”

Well, then.

Yes, But …

I can already hear some of you complaining that this type of “mixing” doesn’t actually mean people are actually mixing—it just means they’re in the same places at the same times, so who cares. There is some merit to this critique, as the authors themselves acknowledge that they can’t guarantee people are actually interacting with other groups when they go out to eat or to buy a gadget. But, leaving aside the fact that most of us do interact with strangers when we’re waiting for a table or takeout or grabbing a drink at the bar or standing in the aisle deciding the best doohickey or watching the Big Game or singing along to a chain’s special version of “Happy Birthday”, mere exposure to people of a different economic background does seem to matter.

Previous research shows, for example, that this exposure (particularly of the poor-to-rich variety), is an important determinant of actual relationships, broader “social capital,” and economic mobility. As one recent and influential study put it, exposure is (along with friendships) “strongly predictive” of a place’s “causal effects on upward mobility, implying that moving to a place with greater exposure … at an earlier age increases the earnings in adulthood of children who grow up in low-income families.” Cross-class connections, in fact, “boost social mobility more than anything else, including racial segregation, economic inequality, educational outcomes, and family structure,” and lack of exposure can be a big barrier to this economic connectedness.

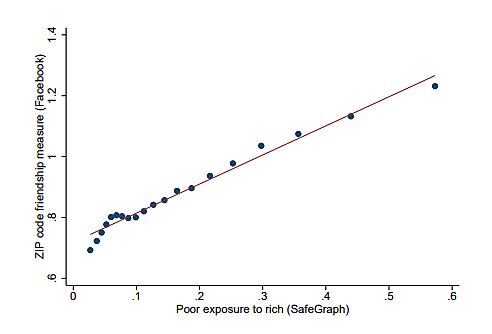

Massenkoff and Wilmers also anticipate this criticism and thus check and confirm their work in several ways. Most notably, they compare their results to zip-code level data on cross-class Facebook friendships (from the aforementioned study) and find that, “in ZIP codes where poor people encounter a higher share of rich people in their daily activities, there’s a higher degree of cross-class friendships as measured in the Facebook data. This confirms that our activity-based measures are tied to another real-world outcome of social connectedness.” As you can see in this chart, the relationship is pretty tight:

Based on these other robustness checks, they conclude that “cross-class friendships … and cross-class interactions remain closely linked.”

And, to recap, chains are where cross-class interactions happen most.

Okay, Fine, So What?

None of this means, of course, that subsidizing Chili’s or whatever will solve America’s social cohesion issues. And pubs and cafes have long served as “social mixing” places—something that’s not just a TV cliché but also recently confirmed by other research on the issue (cool interactive map here, by the way). So, sure, some of this isn’t exactly a revelation.

But the findings here, assuming they’re legit, still matter for several reasons.

Most obviously, there’s been a lot of ink spilled in recent years on how “third places”—neutral places outside the home and workplace where people are more likely to interact—are important for social harmony and equality and thus in need of government support. Yet most policy proposals in this regard target the typical “communitarian” establishments—public (parks, museums, libraries, etc.) and private (churches, civic organizations, etc.)—while ignoring or even denigrating the big commercial places that, it turns out, are quietly mixing rich and poor Americans best. Even worse, many localities have gone so far as to ban “big box” retailers and chain restaurants on expressly communitarian grounds (though perhaps this trend is changing).

To the extent policymakers do want to boost other types of third places, moreover, they’ll need to address residential segregation—and the policies driving some of it. This includes, especially, restrictive zoning policies that build high walls around affluent neighborhoods and public-school systems that encourage the wealthy to pay to get inside those walls (because that’s where the “good schools” are).

Time for a policy rethink, communitarians.

Second, these findings are a pretty clear strike against the trendy anti-corporate rhetoric from populists on the left and (especially these days) the right. We’re constantly told, for example, how “rampant consumerism” destroys our communities and increases isolation. Yet the places in America today that, for better or worse, are actually the most open and socioeconomically diverse—thanks to their affordability, consistency, and commonness (yay, capitalism)—are the places these and other critics are most likely to denigrate. Preferred alternatives, meanwhile, provide fewer opportunities for cross-class connection and can even boost isolation. Thus, contrary to what you might read, “bougie” consumerism and community are not mutually exclusive. And efforts to restrict or destroy the much-derided icons of American mass consumption—both the companies and the policies that support them—could undermine the very cross-class community bonds that so many critics of modern capitalism claim to champion.

Finally, there’s something remarkable that, for all the talk about skyrocketing economic inequality in the United States, the findings show again that there’s been a great leveling of American society in terms of what we consume and where we consume it. Yes, of course, we remain an unequal society in lots of ways (mostly for the better, IMO), and the super rich among us on their yachts and spaceships probably aren’t getting their pancakes at IHOP. But there’s far more intermingling of America’s regular-old rich and its poor—dining at the same places and buying/using the same stuff—than there was back in the good ol’ days before the Great Enrichment. And we have ubiquitous, cheap, tasty stuff to thank for some of that.

So go ahead and pass the properly constructed nachos, friends. You may be doing society a favor when you do.

Chart of the Week

Immigrants have founded a lot of billion-dollar U.S. companies