Dear Capitolists (Capitolisters? Capitolistes?),

I had originally planned to ease you into the whole “policy analysis” thing here at Capitolism by starting with a little “how to think” primer, but then, as the saying sorta goes, we got punched in the mouth by the Mike Tyson of Bad Policy Ideas—the recent order from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) “temporarily halt[ing] residential evictions to prevent the further spread of COVID-19” until December 31, 2020. The CDC eviction moratorium has it all: Good intentions, urgency, poor design, a small group of (potential) winners and a much, much larger group of direct (intended) and indirect (unintended) losers—including some (many) of the aforementioned winners.

It’s seriously just too good (bad) to pass up. So we won’t.

Before we get to that, however, let’s be clear: COVID-19 has imposed severe—really severe—financial and other burdens on many Americans, especially low-wage workers concentrated in leisure and hospitality jobs, or “front line” industries. As economist Doug Holtz-Eakin of the American Action Forum notes, moreover, Census Bureau data indicate that, due to COVID-19, rent is already a major source of this financial distress for millions of Americans (emphasis mine):

Overall, 19.7 percent of [Census] respondents indicate that they did not make last month’s rent payment. This… would imply that nearly 8.5 million households are already behind on their rental payments.… Looking forward, one would expect the number to rise as durations of unemployment lengthen. There is some evidence of this tendency, as 14.1 percent of households have “no confidence” that they will be able to make next month’s payment and 19.9 percent have only slight confidence of their ability to pay. That totals to 34 percent of all households — 14.6 million households.

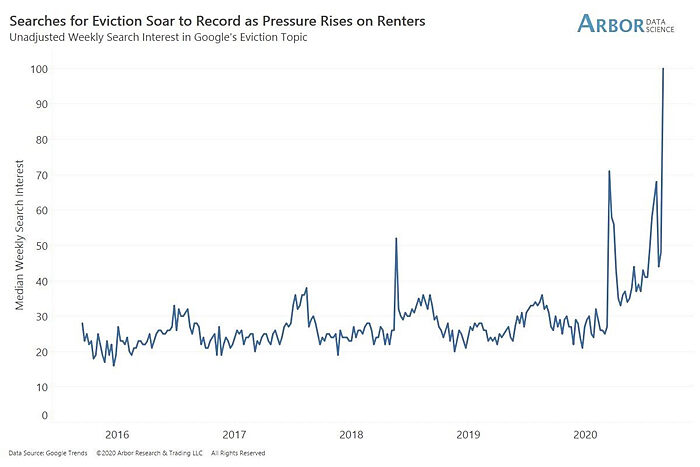

Other indicators, such as Google searches for “eviction,” also indicate increasing housing distress (though some of that is probably due to the CDC order):

So, we’ve established that missed rent and evictions could soon be (already are?) a serious economic problem. However, as we’ll discuss a lot here at Capitolism, the mere existence of a serious problem does not justify any and all federal government “solutions” thereto.

And the CDC’s “solution” here is a perfect example of why.

The CDC order bars any landlord from evicting “any covered person from any residential property in any jurisdiction to which this order applies during the effective period of the Order” (i.e., September 4, 2020 to December 31, 2020). A “covered person” is essentially anyone who expects to earn less than $99,000 ($198,000 for couples) this year and certifies, via a form they provide their landlord, that they’re “unable to pay [their] full rent or make a full housing payment due to substantial loss of household income, loss of compensable hours of work or wages, lay-offs, or extraordinary out-of-pocket medical expenses” and “would likely become homeless” if evicted. A “covered jurisdiction,” moreover, is everywhere in the United States that does not already have an equivalent eviction moratorium in place, along with American Samoa, “which has reported no cases of COVID-19.” Importantly, the order makes clear that this is not a rent exemption: Beneficiary renters are still on the hook for any rent payments missed between September and December, plus any “fees, penalties, or interest as a result of the failure to pay rent or other housing payment on a timely basis, under the terms of any applicable contract.”

Ok, so now that we understand the solution, let’s get into its numerous problems. First, as the Cato Institute’s Walter Olson helpfully explains, the CDC order raises major legal concerns, in terms of both its constitutionality (as a valid exercise of enumerated federal power) and legality under the law allegedly authorizing this action (Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act, 42 U.S. Code § 264, if you’re into that kind of thing). On the constitutional issues (and the depressing absence of Congress), George Will elaborates:

A regulation promulgated by the executive branch grants vast — almost limitless, the CDC clearly thinks — discretion to an executive branch bureaucrat, the CDC director, when acting to contain any “communicable” disease, such as a seasonal flu, spread by “infectious agents.” … [T]he CDC has lunged far beyond… the principles of the separation of powers in the federal government, and principles of federalism in the allocation of federal and state powers.

The CDC presents all this as just another anti-infection protocol. Try, however, to imagine an activity or legal arrangement that the CDC, citing the regulation, could not overturn by fiat in the context of even a seasonal infectious disease such as the flu.

Court challenges from aggrieved landlords are inevitable, but the outcome—despite the clear legal questions here—remains unclear.

Second, the order raises a host of economic issues. Most directly, the order harms landlords by essentially forcing them to assume renters’ financial distress. Olson again:

The practical consequences loom large. State moratoria have already inflicted grave losses on many individual owners of rental properties. A federal ban through year end would ensure what would amount to confiscatory outcomes, such as foreclosure and loss of properties, for some landlords that did no wrong.

Landlords—who face fines up to $100,000 and a year of jail time(!) for noncompliance—also fully bear the burden of proof, as the Wall Street Journal helpfully notes: “Tenants must merely sign an attestation.… [while] landlords who want to remove nonpaying tenants would have to prove tenants are lying. Good luck.” Given the penalties and uncertainty, maybe some corporations might try to challenge the order or individual attestations, but millions of aggrieved individual landlords very likely won’t.

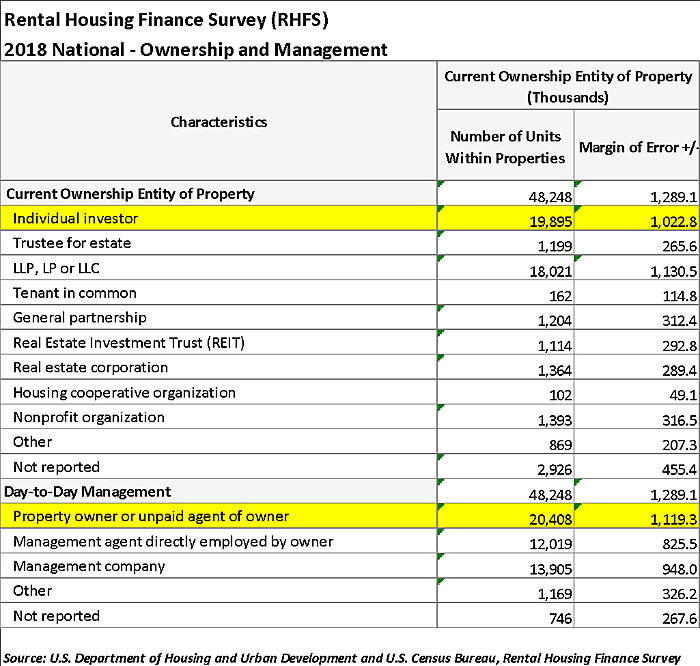

Yes, I said “millions.” Perhaps contrary to conventional wisdom, the direct harms imposed by the order will potentially impact not just (or even primarily) big corporations, but a lot of individual Americans too. Indeed, if you’re an older (ahem) person like me, you probably know one or more people who rent out a modest basement, guest house, or rental property—in each case depending on the rental income to pay down a mortgage on the property at issue. According to the Census Bureau, in fact, about 20 million of the country’s 48 million rental units are owned and managed by individual investors:

Not all of these units are occupied by people making less than the CDC order’s income thresholds, but odds are that many, if not most, of them are. So the CDC order creates a lot—a LOT—of potential “losers” who could suffer months of lost income and have little, if any, real legal recourse.

But wait, there’s more. Thinking economically (as we do here at Capitolism), it’s crucial to consider not just these direct and foreseeable effects but also the unintended, indirect effects of the CDC’s eviction moratorium. And here the order’s harms will probably extend to the very people it’s intended to help—lower-income renters.

To see how, let’s consider the indirect effects of similar government housing market interventions intended to help occupants—in particular local rent control mandates and statewide foreclosure moratoriums during the Great Recession. With rent control, there are obvious winners (existing tenants) and losers (landlords), just like with the CDC order. However, extensive economic research shows that landlords respond to rent mandates in numerous ways that actually end up hurting tenants (especially low-income ones). My Cato colleague Ryan Bourne summarized much of this research in a recent critique of Bernie Sanders’ national rent control proposal, showing how Sanders’ misguided plan would (1) push landlords into converting rental units into non‐controlled forms of accommodation, such as condos; (2) discourage capital investment in new rentable accommodation, thus lowering the overall supply of those units in the market relative to where it would have been; (3) further distort housing markets by generating accommodation that is the wrong size or location for tenants, extensive wait lists, and black‐market behavior; and (4) lead to a deterioration of property quality so that its value more closely matches the controlled rental price. Other research shows how landlords can use “creative ways to recoup their losses” by imposing new fees (such as charging for repairs or the use of amenities).

Some of these well-documented findings might not apply to the temporary CDC order, but many probably will. In particular, we could see landlords across the country:

- Imposing new fees or high interest rates (which the CDC order permits) that existing tenants will have to pay—along with past-due rent—in January 2021;

- Stop providing routine maintenance or other “amenities” to affected properties;

- Decide not to bring new rental supply into the market (e.g., by simply keeping a basement unrented, selling off a rental property, not investing in new properties, or converting a multifamily rental building to condos or Airbnbs); or

- Impose new and more stringent financial requirements on new tenants (e.g., proof of income or a “good” job, or a higher deposit).

The legal uncertainty surrounding the order could further exacerbate these problems, none of which would be good in the longer run for housing markets or tenants, especially poorer ones. And this isn’t just theoretical mumbo-jumbo, either: In the process of writing this, in fact, I heard from a few landlords actually considering one or more of these exact mitigation techniques. I’m quite confident they’re not alone.

At the same time, research on state-mandated foreclosure delays during the Great Recession shows how the CDC order might cause other unexpected harms. For example, a 2015 NBER study examined how foreclosure delays not only increased the stock of delinquent mortgages, but also acted as “an implicit credit line from a lender to a borrower (mortgagor)” and thus reduced pressure on unemployed mortgagors to find a new job, which in turn depressed employment.

In our case, such an outcome might not be so bad in certain COVID-19 hotspots that are still locked down (and you can’t really blame someone for not looking for a new job when much of the local economy is still shut down!). However, the nationwide CDC order makes no such distinctions (except for the bustling labor market of American Samoa) and thus could discourage unemployed renters in relatively low-risk areas from finding a new job. Given the perilous state of the U.S. economy (and the fact that many workers are eager to change industries), this type of stagnation is precisely what we don’t need right now. (It’s also another strike against the CDC order and other nationwide economic mandates that fail to account for major differences in state and local markets… except, of course, American Samoa.)

Meanwhile, research from the Philadelphia Fed on the same foreclosure delays found that they not only imposed significant costs on lenders and servicers (who still had to pay taxes and insurance, and also faced excess depreciation on delinquent properties), but also hurt current borrowers (by discouraging late-stage mortgage modifications), future borrowers (via higher mortgage rates) and certain neighborhoods (with more empty homes), while generating litigation and actually failing to improve foreclosure outcomes.

Again, we can see parallels with the CDC order, especially if it is extended into 2021: Landlords on the hook for potentially significant property costs (and possibly raising other rents to cover for them); tenants and landlords discouraged from coming to a voluntary, private agreement on modifying the lease at issue (another issue real-life landlords mentioned to me); certain rental units falling into disrepair and hurting surrounding neighborhoods; evictions merely delayed into 2021 when the rent (and fees) bills come due; and, of course, plenty of sweet, sweet litigation.

Like I said, this is one awful idea—and an instant member of Capitolism’s Pantheon of Bad Policy.

But, hey, at least we got a good econ lesson out of it.

P.S. The CDC order, I think, is a perfect example of the “elite panic” that Jonah described in Friday’s G‑File: Washington elites (which, yes, includes “populist” Trump administration officials) saw a potential economic and—let’s face it—political crisis in forthcoming evictions, assumed the worst about U.S. landlords, and thought they knew “better than the people on the ground how to adapt and fix things.” So they stepped in with a legally radical and poorly considered mandate that not only imposed significant economic costs, but actually thwarted voluntary efforts by well-intentioned tenants and landlords (“the people closest to the actual problems”) to adjust their contracts and muddle through these difficult times. What a shame.

Chart of the Week

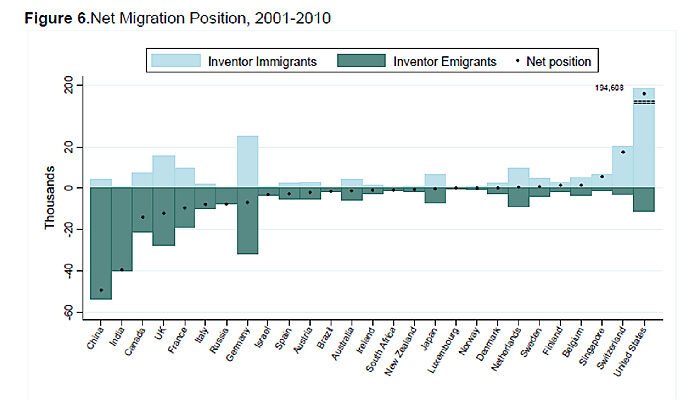

Seems pretty idiotic (to me, at least) for America to throw this away (source):

BONUS Chart of the Week

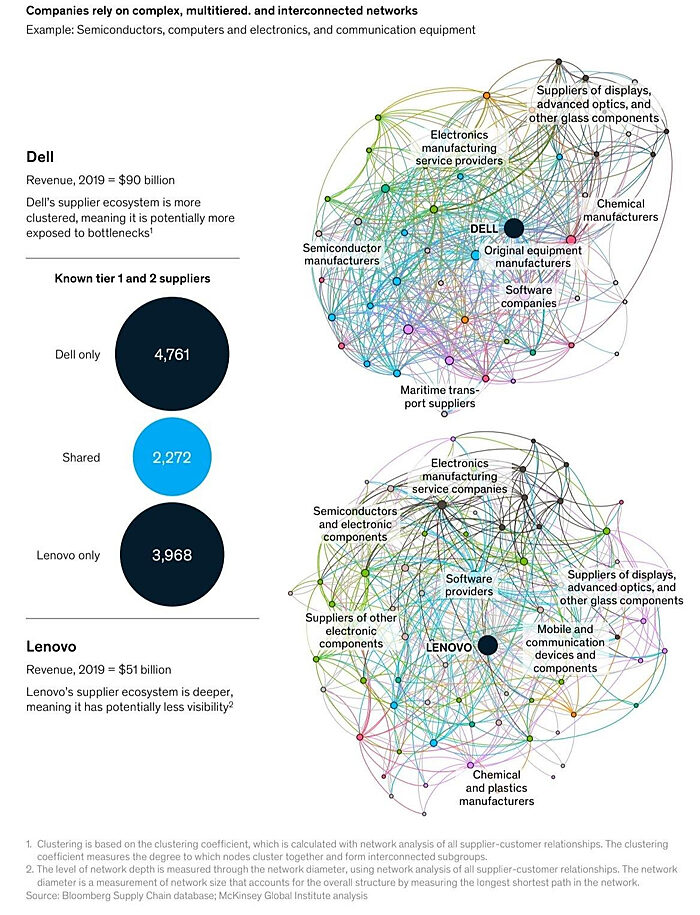

It’s so beautiful (source):

The Links

The new Economic Freedom of the World report is out, with good news globally and bad news locally

Interesting new research challenging the “declining labor share” riddle

Biden’s Buy American Plan is Bad

How the federal government ushered in America’s physician shortage

On COVID-19, changing US consumption habits, and inflation

The Western wildfires are a massive, multi-decade public policy failure

Arnold Kling offers a real definition of “libertarian”

I support GPT-3 because it tells it like it is (UPDATE: GPT-3 Respond)

This is really hard work [Editor’s note: Mature subject matter but totally SFW]