On November 5, 2024, Californians will vote on Proposition 33, a measure that would empower local California governments to institute more extensive rent control laws.

Rent controls are government-imposed limits on how much landlords can charge or increase their rent prices each year. Proposition 33 would repeal the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, a state law that currently prohibits local governments from applying rent control to single-family homes, any housing built after 1995, or the setting of the rent that a landlord can charge a new tenant. If passed, Proposition 33 would thus give cities and counties a much broader base of properties and tenancies on which to impose rent control, including new developments and single-family homes.

This is but the latest stage in California’s long tug-of-war over rent control and other landlord-tenant regulations. Most Californian cities with rent control, including Los Angeles and San Francisco, introduced them in the 1970s. This proliferation of price controls triggered an organized pushback from landlords, who sought ideally to preclude rent control on a statewide basis, or at least ensure “vacancy decontrol” and less stringent eviction protections, such that they could reset rents to market rates between tenancies or reclaim properties for other purposes.

Eventually, landlords won a partial reprieve through the 1985 Ellis Act, which stopped local governments from blocking evictions if the landlord wanted to take his or her property out of the rental sector. The big victory, however, came with Costa-Hawkins, passed in 1995. It de-fanged rent control efforts by precluding rent regulation statewide for single-family homes and those built after 1995. It also allowed landlords to reset rents between tenancies, so keeping rents anchored to their market rates in the medium-term.

Recently, however, the pendulum has swung back. In 2019, Governor Gavin Newsom signed a state-wide rent control law for buildings over 15 years old, albeit still exempting most single-family homes and condos. Under the law, rents can only be increased each year by a maximum of 5 percent plus local inflation (up to a maximum of 10 percent).

That price control may sound like quite a high ceiling for most years in most places — and so not particularly binding. Yet it was accompanied by “just cause” regulations for the same properties that put the onus on landlords to provide specific, government-approved reasons for why a tenant that has been renting a property for over 12 months would be evicted.

This significantly raised costs and risks for landlords further. If landlords wanted to remove a troublesome tenant for non-payment of rent or other lease violations, landlords now risked court proceedings for which they had to provide evidence that their eviction complied with the law. If the landlord was simply trying to reclaim the property for other uses, or began to find renting too much hassle, he or she had to provide tenants with relocation assistance. The measures amounted to a watering down of property rights.

The mere act of passing this legislation, of course, opened the way for more aggressive local ordinances by sending the message that rent control and eviction restrictions were back. Little surprise, then, that in both 2018 and 2020, efforts to repeal Costa-Hawkins were attempted, albeit failing.

Now, after a bout of high inflation and with the Democratic presidential candidate endorsing a national rent control proposal, will it be third time lucky for campaigners with Proposition 33? This time the ballot initiative is comprehensive, not only seeking to repeal Costa-Hawkins but also prohibiting the state “from taking future actions to limit local rent control,” thus granting cities almost full autonomy over housing regulations.

The Economics of Rent Control

Repealing Costa-Hawkins would remove statewide restrictions on the coverage and scope of local California rent control laws. The impact of its removal will thus depend on the specific rent control laws that local governments adopt, how tight any subsequent rent controls bind, and whether those controls are supplemented with other eviction restrictions. Nevertheless, Proposition 33 could lead to a major shift in rent control coverage.*

Localities could theoretically expand rent control to all rental properties built after 1995, apply rent control to single-family homes and condos that are currently exempt, and even control rents between tenancies. Given there are an estimated 2.1 million single-family rentals in California and 3.1 million housing units built after 1995, we are talking about hundreds of thousands or even millions of additional properties potentially being covered.

Again, the full economic impacts will depend on the specifics of the local controls adopted. But there’s a reason, generally, that rent control is opposed by the overwhelming majority of economists. As Jeff Miron and Pedro Aldighieri explain in The War on Prices, rent control tends to lower the quantity and quality of rental accommodation, worsen landlord-tenant relations, and make properties less valuable, thus reducing property tax revenues.

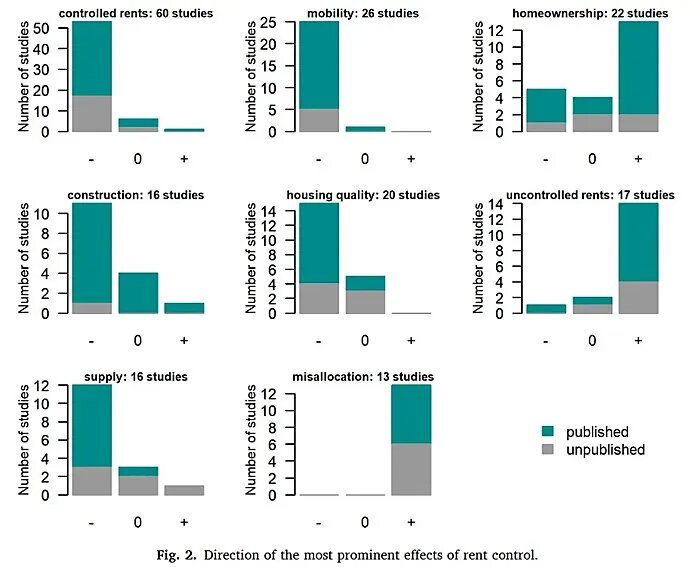

A recent meta-study aggregated across different forms of rent control confirmed these conclusions. As we’ve written before, Konstantin Kholodilin’s summary of over 100 empirical studies found that while rent control typically lowers rent prices for covered units, it also reduces tenant mobility, creates housing shortages, leads to higher rents for uncontrolled units, diminishes rental housing construction, and results in lower-quality rental housing.

The economics to explain why is fairly simple. A rent control that holds the rental price of properties below market rates will produce an excess demand at the restrained price — a “housing shortage.” That’s because the lower price encourages landlords to take their rental units off the market and sell them for owner occupation, live in them, or put them on AirBnB, while the lower mandated price encourages more would-be tenants to seek rental properties. In fact, if rent controls apply to new construction, or landlords suspect they might be expanded to cover new properties in future, they can deter new building too. This all creates a fundamental imbalance between the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded.

In 1994, a ballot initiative in San Francisco broadened rent control to include small multi-family buildings built before 1980 that were previously exempt. This change enabled economists Rebecca Diamond, Tim McQuade, and Franklin Qian to examine affected landlords’ decisions relative to other property owners of structures built later. The expansion of rent control, the economists found, led to “a 25 percentage point reduction in the number of renters living in rent-controlled units, which was “driven by [landlords] both converting existing structures to owner-occupied condominium housing and by replacing existing structures with new construction [i.e. outside of the controls.]” This fall in the quantity of rental housing supplied, they say, increased overall market rents.

It’s not just the quantity and price of accommodation that rent controls affect. When landlords can’t charge market rents, they have an incentive to try to shift to non-monetary forms of competition. Faced with an excess demand, landlords might, for example, become more discerning about who they rent to, often requiring bigger deposits or discriminating according to income or race or gender or whether a family has children to reduce other risks of renting out their properties. Under rent control regimes where landlords can vary rents between tenancies but not within them, landlords might be biased in favor of tenants likely to move on more often, for example, so that they can keep rents more closely tied to their market levels over time.

Tenants generally face the opposite incentive: enjoying below-market rent is a boon to them and so they are less likely to move, given the resulting loss of subsidy. That can lead to a lot of misallocation, as tenants end up in properties unsuited to their needs and which they don’t value as highly as others would. In San Francisco, Diamond, McQuade, and Qian found that rent control beneficiaries were 19 percent less likely to move, for example. These effects become more destructive the longer rent control is in place.

This conflict of interest between landlords and tenants can be a source of tension. Policymakers worry that without the option to force undesirable tenants out by raising rent, landlords will treat tenants poorly or kick them out on a whim. That’s why rent controls tend to be introduced alongside laws that make it more difficult to evict tenants. Yet these regulations further raise risks for landlords of renting, so compounding the reduction in the supply of properties. The classic 1990 Pacific Heights movie, based in San Francisco, popularized landlords’ frustration about how unruly tenants can abuse these eviction laws, making a mockery of property rights.

Over time, some landlords will react to the below-market rent associated with rent control by adjusting in other ways, such as investing less in maintenance and upkeep, so that the quality of housing deteriorates to reflect the lower rent-controlled price. That’s one reason why rent controls in some cities internationally have created slums. In others places with partial rent control coverage, like New York, rent-controlled properties have still been found to have worse overall building conditions, older appliances and fixtures, and more maintenance problems.

The flipside is also true and found time and again: when rents were de-controlled in Massachusetts, for example, annual investment in housing units more than doubled. Given the broader spillover effects on affected neighborhoods, rent controls can thus depress property values, lowering government property tax revenues. How far that occurs, of course, depends on whether this is offset by the impact of landlords converting rental properties into more owner-occupied condos or rebuilding units to avoid the controls, which can actually encourage higher-priced gentrification under rent control.

California’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office itself notes many of these likely consequences of broadening the scope of rent control. Although Proposition 33 would reduce rents for some renters, it says, others not covered by the law would likely pay more. They also posit that “some renters would move less often,” “fewer homes would be available to rent,” and “the value of rental housing would decline.” They conclude that property tax revenues for local governments would fall due to the declining value of rental properties, while the costs to enforce rent control would rise. It’s a fair summary of the literature.

It’s important to recognize, of course, that tenants lucky enough to keep their properties will benefit financially from rent control. Yet there’s no guarantee these people will be the poorest. Since rent control reduces the quantity of rental accommodation in favor of owner occupation, and the poor typically can’t afford down payments, the poorest can suffer directly from rent control. As noted, rent control also incentivises landlords to discriminate in favor of less risky tenants, meaning that rent control is rarely a transfer from high-income landlords to low-income tenants. And because of the ongoing subsidy of below market rents, rent control can deter mobility for the poor to better long-term job opportunities, even when they do benefit in the short-term from the controls.

In some European cities, so-called “tenancy rent controls” have become popular in recent years as a less extreme form of price control. These impose rent caps within fixed-term tenancies but allow rent adjustments between tenancies — in effect, rent control for fixed terms with vacancy decontrol. The idea is that tenants get some more economic security in the short-term, without the longer-term destructive effects on the supply of property. The problem with this approach is that even these rent controls typically get proposed in the name of improving housing affordability. Given tenancy rent controls don’t reduce rents in the medium-term, landlords come to expect that the resulting disappointment will lead politicians to tighten the laws to control rents between tenancies, as recently played out in Scotland. That encourages landlords to exit the market and spurn new rental developments today. Argentina recently showed how destructive even these laws can be.

Of course, the more stringent the price caps, the stronger the effects. And if Costa-Hawkins is repealed, this will be within the gift of California’s local governments. But the empirical evidence overall shows that most forms of rent control reduce the quantity of rental accommodation supplied, reduces its quality, and lead to less mobility for affected tenants. Does California really have to relearn all these lessons again?

* Already, San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors has passed an ordinance unanimously that would bring buildings built before 1994 into its rent control regime, should Proposition 33 succeed. The current cut-off date is 1979. That would mean 16,000 more units exposed to rent control.