Dear Capitolisters,

A new paper of mine was published at Cato today on the issues of manufacturing, national security, and economic “resiliency”—topics that, thanks to President Trump and China, were already hot pre-pandemic but have only become hotter in the subsequent months. Indeed, as I note in the paper’s introduction, it’s common these days for politicians and pundits of all partisan stripes to propose new U.S. protectionism and industrial policies on the grounds that “free markets” and a lack of government support for the manufacturing sector have crippled the U.S. industrial base’s ability to supply “essential” goods during war, pandemic or other emergencies.

As I explain in the paper, free marketers dating back to Adam Smith openly acknowledge that “national security” may require government interventions, but the “security nationalism” thesis still suffers from many flaws—far too many for a single newsletter to cover and some that are perhaps too wonky for even this audience. However, there’s one issue that is so pervasive, so central to much of American politics (especially the resurgent populism on the right), and so objectively incorrect that it deserves to be addressed here: American “deindustrialization.” It was a cornerstone of Trump’s 2016 campaign and subsequent trade and industrial policy, and in many respects is being echoed by President Biden, who just this week signed a new “Buy American” executive order to (supposedly) “rebuild” the U.S. manufacturing sector.

Yet the “deindustrialization” narrative is, at best, wildly overblown. Let me explain why.

What Do We Mean by “Deindustrialization”?

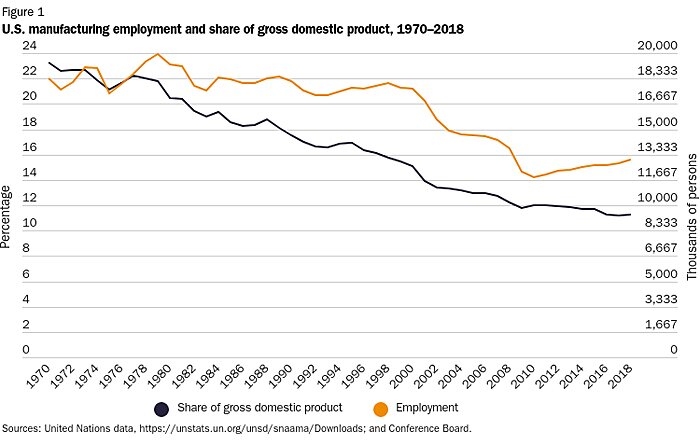

Today’s “security nationalists” often emphasize two trends—declining U.S. manufacturing employment and the sector’s declining share of U.S. economic output (as measured by its percentage of national gross domestic product )—when lamenting American industrial decline and proposing new policies to support domestic manufacturing and national security. Both trends have indeed occurred:

However, these trends provide little insight into the state of the U.S. defense industrial base or government policies affecting it, because they are primarily long-term, global trends disconnected from specific economic policies, whether “free market” or “interventionist.”

-

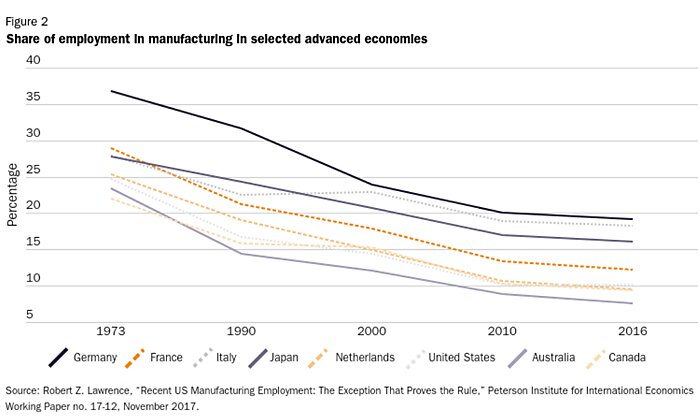

Jobs. The long-term decline in U.S. manufacturing jobs coincided with rising sector output (more on that below) and was mirrored in developed countries around the world—including those like Germany or Japan with economies more centered on manufacturing, with longstanding trade surpluses in goods, or with more aggressive industrial policies. (In fact, since the ’70s, Germany actually lost a larger share of manufacturing jobs than did the United States, as did several other developed countries.)

Since trade often gets the blame for manufacturing job losses, it’s good to add Robert Lawrence’s 2020 examination of 60 developed and developing countries between 1995 and 2011, which found that nations with manufacturing trade surpluses actually experienced slightly larger declines in manufacturing employment than those with manufacturing trade deficits. He also found that manufacturing job losses were as large in countries with “improving” manufacturing trade balances over this period as those with “worsening” ones.

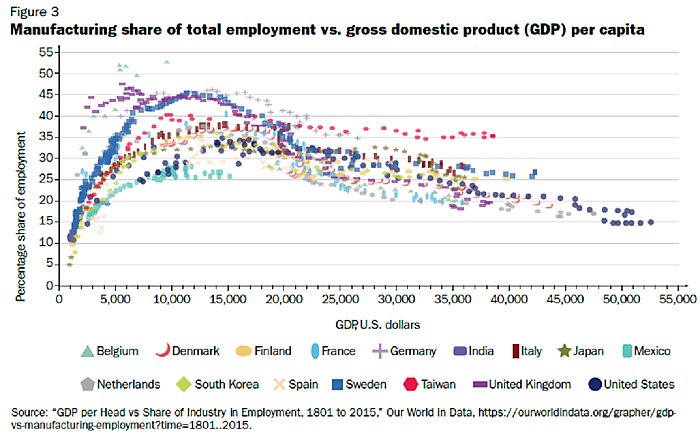

Why? Because manufacturing job loss is less a story of “deindustrialization” and more one of economic development. In general, all countries generally follow the same “inverted‑U” pattern of development, first adding and then losing manufacturing jobs as they get richer (and gaining services jobs over the same timeframe).

-

While manufacturing in some countries represents a larger total share of a country’s domestic workforce than in the United States, the loss of manufacturing jobs—and thus the basis for any “deindustrialization” claim—is happening around the world. (Only Taiwan stands out.) So changes in U.S. manufacturing jobs really don’t provide much insight into the state of American manufacturing or related government policies.

-

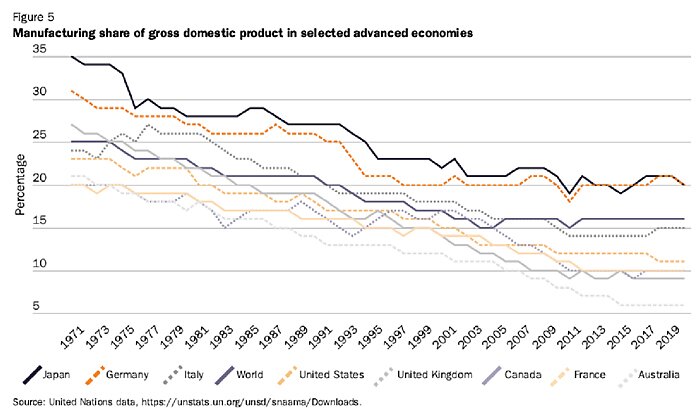

GDP share. Manufacturing’s declining share of total U.S. GDP also reflects secular trends largely disconnected from policy. First, the change in the industrial sector’s GDP share reflects the relative strength of the U.S. services sector instead of the weakness of American manufacturing. Indeed, between 1997 and 2019, output and value-added (basically, sales minus costs) of private service providers increased by about 87 percent and 77 percent, respectively, but the same metrics for U.S. manufacturing increased by a slower-but-still-respectable 18.7 percent and 52.8 percent—continuing long-term trends in these sectors dating back to the 1940s. In other words, both sectors were growing, but the service sector was just growing faster. Hence, its rising share of GDP.

Second, the relative growth of services versus manufacturing (and thus the manufacturing sector’s declining share of GDP) isn’t cause for alarm because it reflects fundamental shifts in consumption patterns in all countries—away from goods and toward services—as they develop. In the United States, this has been going on since the 1950s: U.S. consumers were allocating half (50.3 percent) of their spending to goods in 1960 but only 33 percent by 2010. Over the same period, the U.S. manufacturing sector’s share of U.S. GDP declined in parallel (see Figure 1 above)—a “strong connection” that has been going on since 1900 and that continued through last year when U.S. manufacturers started outperforming domestic service providers because COVID pushed homebound Americans to buy more goods and fewer services.

The same consumption trends are happening all over the world (detailed in this 2012 examination of 31 countries), and they are having the same effect on nations’ manufacturing as a share of GDP.

In sum, both the manufacturing employment and GDP-share trends occurring in the United States—often cited by economic nationalists as proof of severe industrial demise—actually reflect macroeconomic forces affecting most industrialized countries in the same way. These trends thus tell us very little about American “deindustrialization” or previous U.S. trade and manufacturing policy.

The Reality of U.S. Manufacturing and Our Industrial Capabilities

In fact, jobs and GDP share say very little about the nation’s “industrial capabilities” (i.e., its ability to produce the goods that the country needs in times of war or other national emergencies), which along with access to similar capabilities abroad is what the U.S. Department of Defense considers critical for national security.

By this metric, the United States shows little weakness.

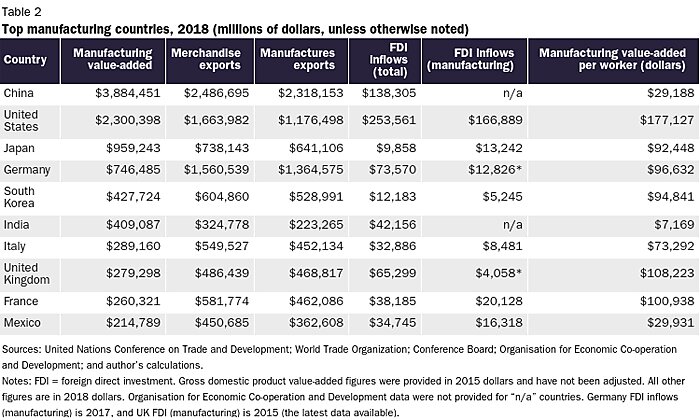

First, despite popular claims that the United States has suffered a broad decline in productive capacity, the U.S. manufacturing sector actually remains among the most productive in the world and has expanded since the 1990s, continuing earlier period trends in output, investment, and profitability that my Cato colleague Daniel Ikenson documented in 2007. As you can see from the table below, the United States continues to be at or near the top of most categories, including output, exports, and investment:

The U.S. manufacturing sector is not only large but also extremely productive, with output per worker outperforming China and all other top manufacturing countries. We’re also a top recipient of foreign direct investment (FDI), with 2018 FDI inflows into the U.S. manufacturing sector alone (almost $167 billion) larger than total FDI inflows into China for the same year ($138 billion).

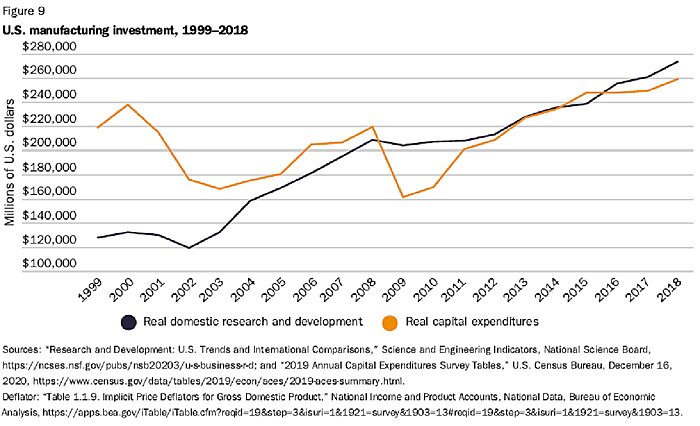

Furthermore, the U.S. manufacturing sector is still growing and a magnet for investment. As already noted, the sector’s real (inflation-adjusted) output and value-added were up significantly between 1997 and 2018. Capital expenditures (capex), research and development (R&D), and FDI have also been consistent and strong since the 1990s, with annual capex and R&D spending both peaking (at well over $250 billion) in 2018.

Finally the sector has also experienced improved financial performance since 2001 (the first year of data available), with inflation-adjusted gains in revenues, post-tax income, and assets. In short, there’s just no evidence of a broad decline in the U.S. manufacturing sector’s industrial capabilities.

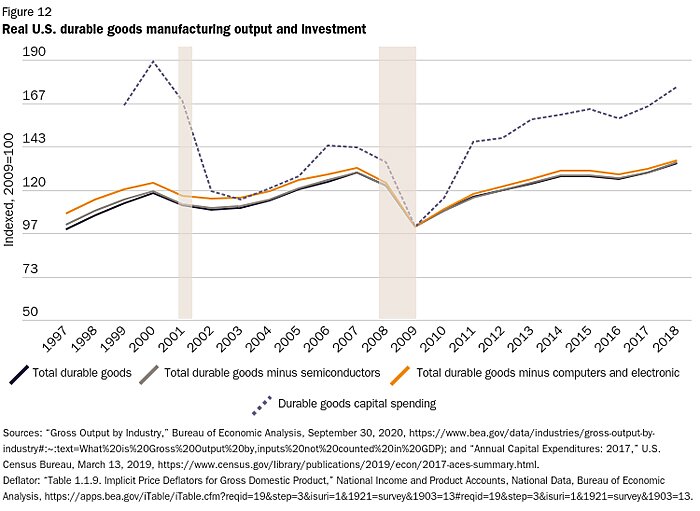

That said, the topline data do hide significant changes in U.S. manufacturing over the past two-plus decades in response to various economic forces (globalization, interstate competition, technology, changing consumer tastes, etc.). It’s not just some big monolith, and certain industries have indeed risen or fallen since the ’90s. But here, again, the story is generally positive, especially in terms of “national security.” In particular, U.S. production of durable goods—particularly aerospace, motor vehicles, metals, computers and electronics, ships, and medical equipment—has increased significantly since 1997 (and not just, as some have claimed, because of hyper-technical changes to computing power):

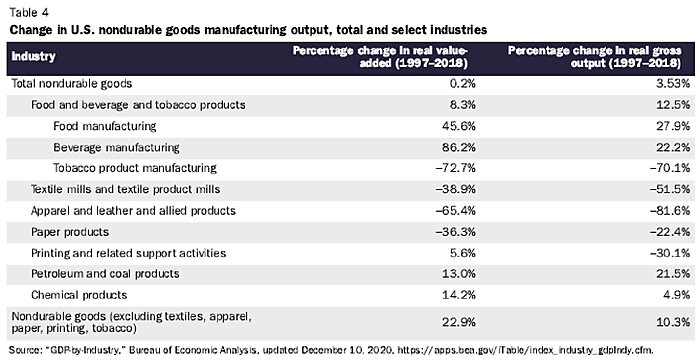

On the other hand, U.S. production of nondurable goods has sagged, primarily driven by declines in textiles, apparel, paper/printing, and tobacco. Even this, however, is not reason for serious concern about American manufacturing. For one thing, many of those declining nondurable industries (and a smattering of durable goods industries too) are still pretty big—the textiles industry in 2018 still generated approximately $54 billion and $18 billion in output and value-added, respectively. Others, such as paper/printing, tobacco, or optical media (CDs!), are simply dying off. And, most importantly, the decliners have been more than offset by the aforementioned gains made by the durable goods sector as well as gains in other, more advanced and capital-intensive nondurable industries like pharmaceuticals or energy.

Notably, the industries most closely tied to “national security”—today’s trendy excuse for new U.S. protectionism or subsidies—haven’t experienced significant historical declines and in most cases have expanded. This includes goods directly involved in national defense (e.g., tanks, missiles, and munitions), as well as those indirectly related, such as metals, electronics, motor vehicles, aerospace products, ships, medical equipment, energy, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals. Although certain subsectors’ output has risen and fallen over different periods (to be expected given business cycles, changing U.S. military operations, and other factors), the overall picture is one of stability and health, not decline.

These data refute the common myth that “unimportant” American industries have driven gains in U.S. manufacturing output—the “we make potato chips, not microchips” argument. The truth is, we make a lot of both.

The data also reveal a more complicated, and benign, picture of American manufacturing over the last few decades: a flexible and dynamic sector that is generally responsive to market forces. Surely, some industries have shrunk, but many others have expanded. Overall, we traded a portion of low-tech or dying industries for a larger amount of higher-tech, often-thriving industries. (As wage data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show, moreover, the latter also tend to pay better.)

It’s a story of disruption, not “deindustrialization.”

Disruption, of course, can still be painful for certain manufacturers and workers. But the sector’s flexibility also can prove critical in times of unexpected national emergency, and recent experience bears this out. According to a new U.S. International Trade Commission report on trade and domestic production of essential medical goods during the pandemic, for example, U.S. manufacturers and global supply chains responded quickly to boost supplies or make new drugs, medical devices, PPE, cleaning supplies, and other goods. Particularly resilient were the industries making pharmaceuticals, medical devices, N95 masks, and cleaning products (including hand sanitizer), but even in other areas where the U.S. had less pre-existing production capacity, the ITC found that serious shortages were short-lived, filled in quickly by imports and new U.S. production (either new companies or established ones changing their production lines to make high-demand products). Only rubber gloves continued to be a concern going into 2021, primarily due to the limited availability of natural rubber (sourced primarily from Malaysia).

Overall, the ITC report shows a large and diverse U.S. medical goods market in which both domestic production and imports vary according to comparative advantages and worked in tandem to satisfy consumer demand—demand that skyrocketed in response to a once-in-a-generation pandemic and was, by far, the biggest supply chain challenge. In short, the pandemic severely stressed the system, but the system ended up working pretty well, and U.S. manufacturers played a prominent role.

Anecdotal evidence backs up the ITC’s findings. Many U.S. companies shifted operations to produce high-demand PPE during the pandemic, an example of the U.S. manufacturing sector’s pre-existing industrial capacity and the aforementioned flexibility. Others were drawn into the market: online crafts retailer Etsy, for example, sold more than $600 million in face masks during 2Q and 3Q 2020 (12 million units in April alone), and “more than 110,000 sellers sold at least one mask between April and June.” Although short-term gaps in U.S. PPE supply inevitably emerged (due to that astronomical demand, pre-pandemic stockpiling mistakes, or other issues), they were filled in by foreign producers and the aforementioned stockpiles. As of August 2020, for example, NIOSH-approved N95 masks were readily available for individual or bulk purchase on websites like Amazon.com. Several members of Congress have even gone so far as to write to President Biden this week complaining about a glut of U.S.-made PPE (which now the government obviously needs to buy or something)!

Surely, things weren’t—and still aren’t—perfect out there, and some gaps in supply could take months (if not longer) to get right. But the situation is hardly the doom and gloom that economic nationalists, preaching “deindustrialization,” predicted in the spring. That result is primarily due to the rapid adjustment of the U.S. manufacturing sector (and those dreaded global supply chains) to the new pandemic reality—an adjustment that the nationalists apparently never saw coming.

Summing It All Up

So the U.S. manufacturing sector’s declining share of GDP or shrinking workforce parallel similar trends around the world and tell us little about the sector’s overall health. Meanwhile, the most revealing data—on output, investment, and financial performance—show a large and dynamic industrial base that remains a global powerhouse. Some low-wage, low-tech, or dying industries have declined, but many others have grown (while others still have treaded water). That’s hardly “deindustrialization.” (And whether the U.S. government should nevertheless try to “reshore” those low-tech industries is a question for another time.)

Now, just because things aren’t as dire as claimed doesn’t mean there aren’t plenty of policies that the U.S. government could implement to help make the manufacturing sector even stronger. I detail a lot of these at the end of my paper, but here’s a shortlist:

-

Unilateral liberalization of tariffs on industrial inputs. President Trump’s tariffs—and others like them—have been repeatedly found to harm the U.S. manufacturing sector and antagonize allies while providing little long-term benefit to the protected domestic industries at issue. Eliminating import restrictions—and reforming the laws that let them be imposed so easily—would thus provide an immediate boost to the U.S. manufacturing sector.

-

New trade and investment agreements with U.S. allies. The U.S. government should liberalize trade and investment with allies by (1) expanding the National Technology and Industrial Base (a narrow agreement that allows member countries—currently the U.S., Canada, UK, and Australia—to pool critical resources and R&D) to include allies and innovative manufacturing nations, such as Finland, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, South Korea, Singapore, Switzerland, or Sweden; and (2) considering new comprehensive free trade agreements with these and other countries.

-

Additional corporate tax reforms. The federal government and the states should further reduce corporate tax rates, which combined remain above the OECD average and are shouldered in large part by workers and consumers. The government should also expand and make permanent the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s temporary “full expensing” provision (“100 percent bonus depreciation”), which allows U.S. businesses to write off certain business investments immediately and fully. These reforms would benefit all companies, but would particularly boost the U.S. manufacturing sector. Researchshows, for example, that full expensing increases investment, jobs, and economic growth, and that a permanent and expanded version (covering structures like factories) would especially benefit U.S. manufacturers.

-

Improving human capital. To address immediate concerns regarding the dearth of qualified U.S. manufacturing workers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields, the government should significantly expand high-skilled immigration, restrictions on which have been shown (1) to encourage multinational corporations to offshore jobs and R&D activities to their affiliates in more welcoming countries; and (2) to benefit potential U.S. adversaries, especially China, in terms of new jobs, new businesses, and new innovations.Longer term, private sector training and apprenticeship programs, such as the employer-funded Federation for Advanced Manufacturing Education (FAME) program, can equip native workers for the future needs of advanced manufacturing industries and supplement federal, state, and local government educational policies.

-

Eliminating “never needed” regulations. According to the ITC, onerous federal regulations were among the biggest impediments to increased U.S. manufacturing of essential medical goods during the pandemic. At the same time, state and federal governments temporarily suspended hundreds of these regulations to boost domestic production, investment and adjustment, revealing in the process these “never needed” regulations discouraged economic growth and dynamism while providing little, if any, public benefit. Repealing or reforming these regulations would therefore not only boost economic growth generally but also American manufacturers directly—all to the benefit of economic “resiliency.”

As noted, the paper has plenty more on trade, national security, and economic resilience, if you’re interested. Enjoy.

Chart of the Week

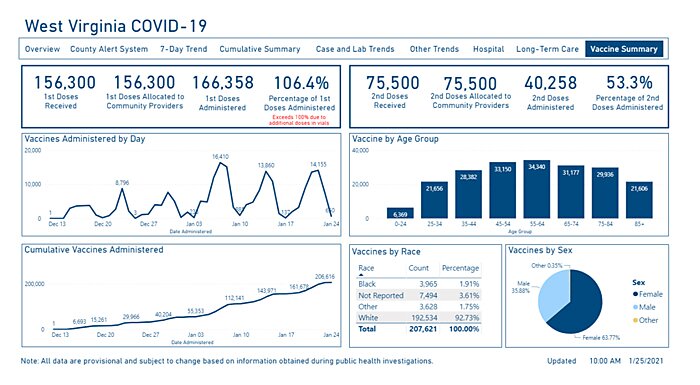

West Virginia is just dominating its COVID vaccine rollout.

The Links

Kevin Williamson on “Buy American”

New review of the econ literature on the minimum wage (spoiler: lunches still aren’t free) (Cato’s Ryan Bourne comments)

In 2020, China (probably temporarily) overtook the U.S. as the top recipient of foreign investment.

But China’s economic ascendance isn’t guaranteed

Political weaponization of the Fairness Doctrine

Israel’s vaccination effort is working (More)

Libertarianism in a pandemic: pretty good, actually

The benefits of an open society

Some problems with “moonshot” industrial policy