On Friday, the Biden administration announced a “temporary pause” of pending requests for permission to export liquefied natural gas (LNG) outside the United States. Given the much-publicized role that U.S. LNG has played in global energy markets in recent years (see last year’s Capitolism for more), the Biden move was widely criticized—and no, not just by oil and gas companies and partisans (here’s the Washington Post editorial board, for example). The move also, however, was narrowly praised by the young eco-warriors that the White House was clearly targeting—fossil fuel opponents who vigorously lobbied for a blockade on U.S. LNG and related export facilities.

Readers here will be unsurprised to learn that the critics are (mostly) right: The decision is a bad move that reeks of politics and injects more risk and uncertainty into an already risky global energy market. However, it’s also probably not the epic catastrophe that some of the more, ahem, vocal critics claim. And only time will tell if the move’s political benefits outweigh the economic, environmental, and geopolitical risks that it creates. In the meantime, however, the episode provides another glaring example of how U.S. law far too often gives far too much discretion to American politicians and bureaucrats, to the detriment of not just those involved but also the broader U.S. economy and national security.

It is, as P.J. O’Rourke famously said, another lesson in why “giving money and power to government is like giving whiskey and car keys to teenage boys.” Only in this case, the car is actually a $260 million ship carrying some of the most economically and geopolitically important energy in the world.

What Friday’s White House Announcement Does and Doesn’t Do

I first documented some of the problems with the U.S. natural gas export system in a 2013 paper for the Cato Institute. Here’s how that system works: Under current law (the Natural Gas Act of 1938 and its amendments), a party wishing to export American natural gas must obtain a license from the Department of Energy (DOE), which will provide such authorization unless exportation is not “consistent with the public interest.” (If you’re exporting LNG, you also need to get the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approval to build an export facility, but that process isn’t at issue today.) Because making and exporting LNG requires giant facilities and ships, export applications are made years in advance of actual shipments being made and are typically linked to massive, billion-dollar projects and big contracts with foreign buyers (which make the projects financially viable). Reject an export license application, and the whole thing can fall apart.

Such rejections aren’t really an issue for exports to U.S. free-trade-agreement (FTA) partner countries because licenses are, with very limited exceptions, issued automatically. They’re deemed consistent with the public interest, and DOE must grant license applications “without modification or delay” when the customers at issue are in an FTA country. In practice, approval takes a few months—a relative breakneck pace for modern American bureaucracy.

However, the United States doesn’t have a lot of FTAs, and this is where last week’s announcement comes in. Exports of gas to non-FTA countries—a big group that includes the U.K., all of Europe, Japan, India, and most of Africa and Latin America—are legally presumed to be in the public interest, but DOE can rebut the presumption with evidence to the contrary. And because U.S. law doesn’t establish any binding, objective criteria that DOE must apply when making a “public interest” determination, the agency (and thus the White House) retains complete discretion over whether to grant a license and the methodology for making that determination. On Friday, the Biden administration announced that DOE is reviewing the current methodology, which was last updated in 2018, and that all non-FTA export license applications are paused until that review is complete.

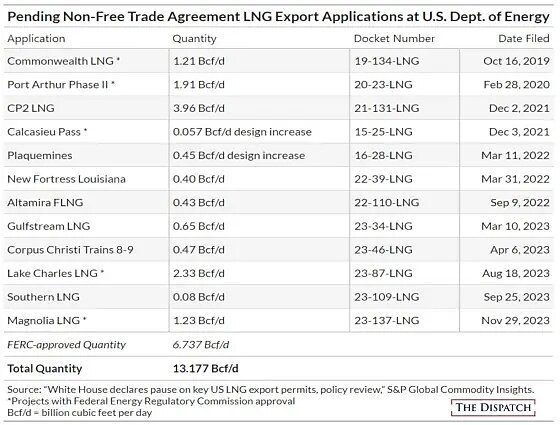

The White House’s announcement thus puts pending LNG export applications, the projects to which they’re tied, and any future licenses/projects at risk. Per S&P Global (see table below), licenses/projects totaling around 13 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d)—more LNG than the United States exported last year—are pending at DOE right now. About half of that (asterisks in table) involved export facilities already approved by FERC, and those projects are now the ones at the most immediate risk of getting sidetracked (or worse) because of DOE’s delay.

On the other hand, the DOE announcement won’t touch the U.S. LNG export projects that have already received an export license—including both those that are already operational and those currently under construction. As the White House and its advocates will tell you, that’s a lot of current and future LNG exports, and Energy Information Administration data show they have a point: The United States was the world’s largest LNG exporter last year and, even accounting for now-paused license applications, will add a significant amount of new export capacity in the next couple years:

It’s thus no real surprise, then, that natural gas spot market prices (here and abroad) haven’t made any wild moves since Friday’s announcement; or that the only big stock moves were for U.S. companies making LNG export equipment (sucks for them, of course); or that European policymakers, while less than thrilled with the White House’s decision, aren’t freaking out either about near- or even medium-term energy security issues.

But It’s Still Bad Policy

That the announcement didn’t immediately crater global gas supplies, crush domestic energy producers, or undermine U.S. foreign policy objectives does not, however, mean it was actually good policy. In fact, there are plenty of reasons why the move is wrongheaded and might pose bigger problems down the road.

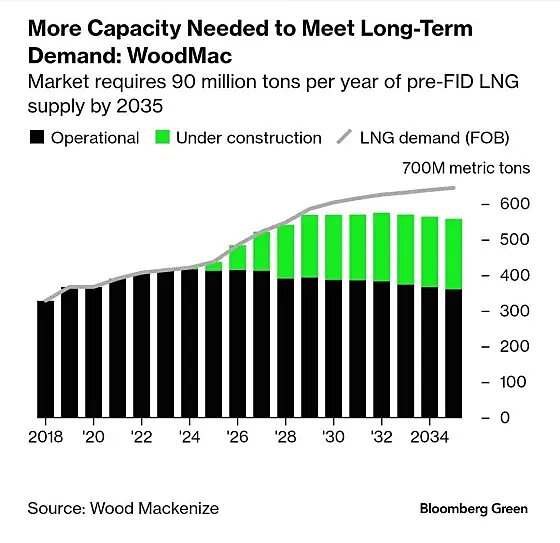

For starters, we shouldn’t dismiss the prospect of harm to global energy markets and U.S. geopolitical interests just because short-term (spot market) natural gas prices and energy company stocks didn’t go haywire overnight. As Bloomberg reported earlier this year, the current global gas market is mostly in balance, but demand is projected to outstrip supply in just a few years—and this was before last Friday’s pause that puts a good chunk of future supply at risk:

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine and recent turmoil in the Middle East have shown, future non‑U.S. gas supplies are far from guaranteed. Indeed, just last week the world’s second-largest LNG exporter, Qatar, announced that it was delaying cargoes to Europe because of the Houthi/Red Sea crisis.

Problems can also arise at current U.S. facilities. Also last week, for example, Freeport LNG announced a monthlong outage at its Texas facility—the latest in a long string of incidents there—because of a major winter storm. Maybe these situations and other global tensions calm down in the coming months; maybe they don’t. What’s clear is that the Biden administration’s pause just made the margin of error a little smaller.

No wonder, then, that officials in Europe and Japan, while not freaking out, have nevertheless expressed concerns about future “policy-driven” gaps in available gas supplies and are now seeking alternative, just-in-case suppliers—including in Russia (natch).

The LNG pause further increased market uncertainty by amplifying the politicization of U.S. export restrictions, thus likely depressing future investment in LNG exports regardless of whether the pause is lifted in a few months. Given the discretionary nature of the U.S. export licensing system, investors have always faced some theoretical risk that the government (DOE or FERC) would delay or reject their projects. However, that risk has in practice been low for about a decade: Per DOE, every non-FTA export application has been either voluntarily withdrawn or approved by the agency, typically a couple years after it was filed.

After Friday, however, the risk of rejection or at least longer delay has markedly increased. Investors are sure to take note, especially for projects in their earliest stages. A mountain of research shows that policy uncertainty chills private investment, and there’s no reason to think that this move won’t do the same. (Indeed, it’s precisely what anti-LNG activists are hoping for.)

As former DOE official Jeff Kupfer reminded us over the weekend, moreover, recent history gives energy investors reason to worry that this “short” delay won’t actually be so short:

In 2010 a company called Cheniere Energy applied for the first LNG export license. The project sailed through the conditional approval process in about eight months without drawing much attention. Another company, Freeport LNG, applied for an export license around the same time, and more applicants followed. But environmental groups took notice as President Obama began his re-election campaign. The Obama administration put decisions on hold, the Energy Department commissioned a study on the effects of exports, and after Cheniere Energy got final approval in 2012, no further LNG final export permits were issued until 2014.

Investors are now stuck hoping that a similar thing doesn’t happen this time around—and hope isn’t exactly what you want when you have billions of your own dollars on the line.

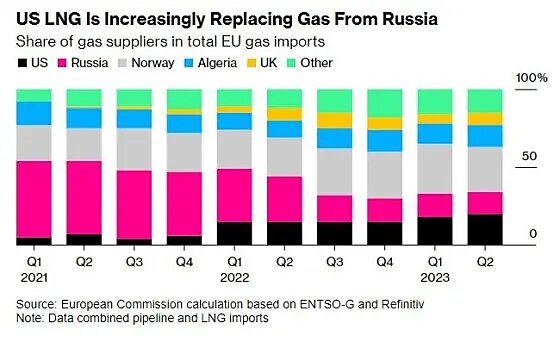

The risk to global energy markets is further amplified by the somewhat unique and flexible nature of the American gas exports at issue. As we discussed last year, one of the big reasons why U.S. LNG was able to ride to Europe’s rescue after Russia invaded Ukraine was because profit-hungry traders could divert those shipments to higher-priced Europe. That’s because most U.S. LNG being sold was different from the fixed, long-term contracts that state-owned sellers in Qatar, Russia, and elsewhere:

A relative geographical closeness meant savings for traders sending US cargoes to Europe instead of Asia; the affluent region also had more purchasing power to snag the pricey shipments. Also working in US gas’s favor: Its contracts are nearly always written to be “destination flexible,” meaning traders are allowed to divert tankers if necessary when the price is right. They can even cancel shipments if demand suddenly collapses. The EU’s LNG imports surged by 60% in 2022, and abundant LNG from Europe’s long-held political ally was the biggest contributor by far.

According to Bloomberg’s Liam Denning, around two-thirds of the capacity scheduled to come online in the United States (including the now-paused projects) is similarly flexible. It and existing supplies can thus more easily serve as a safety valve for whatever region needs it when whatever shock arises. As we saw in Europe last year, that means more global market stability and U.S. geopolitical heft. As Ben Cahill, an energy expert with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, put it in early January (i.e., before last Friday’s announcement), “The combination of fast-growing U.S. LNG volumes and greater destination flexibility has contributed to a more fluid, commoditized global gas system. … The United States now plays a critical balancing role in the global LNG market, adding supply and flexibility that has boosted global energy security.”

Well, it did.

Put it all together, and there are clearly more risks today of a substantial future supply-demand imbalance than there were last Thursday. And it’s only natural to assume that these risks will be reflected in the long-term (20-year) contracts that are standard for much of LNG trade (even some in the United States). According to S&P Global, in fact, industry participants are already worried that “the policy move could cause some proposed projects to stall and hinder long-term contracting,” and “impacts to the LNG market could be far-reaching if final investment decisions on pending US projects are delayed or halted because of policy concerns.” That’s a recipe for higher prices and fewer contracts, even if the pause gets lifted later this year.

In short, Friday’s announcement didn’t collapse global energy markets, but it did make them a little bit weaker, a little less transparent, a little more costly, and a little more unpredictable. That’s an especially ironic result coming from a Biden administration that routinely justifies its nationalist economic policies—tariffs, subsidies, etc.—on “economic resiliency” grounds. (“Resiliency” for me, but not for thee, I guess.)

And for what? Well, if you’re to believe the White House, it’s all to fight the “existential threat” of climate change. But here, too, the policy fails.

As Bloomberg’s Denning and others have explained, the lone study showing LNG to be worse for the climate than coal (thanks mainly to methane leaks) hasn’t been peer-reviewed. Not only that, it was authored by a highly controversial Cornell university professor whose research has been widely criticized by other scientists (and keeps changing). Just as importantly, there’s a lot of good, peer-reviewed research from academia, government, and even the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change showing LNG can help reduce global greenhouse gas emissions because it often replaces dirtier coal or traditional biomass energy (mainly wood burning). That’s especially important in developing countries where such fuels remain common—and where some of that now-paused U.S. LNG was headed. For example, in the Asia-Pacific region, Denning notes, “coal generates 57% of electricity, representing 80% of coal-fired power worldwide.” Here’s how this works in practice:

2) The world needs U.S. LNG. It helped Europe survive Russia’s natural gas blackmail. But the rest of the world needs it too. When U.S. gas went to Europe, Pakistan was left without & 200+ million lost power. So it decided to quadruple use of coal. https://t.co/8skkCTMh6y

— James Coleman (@EnergyLawProf) January 26, 2024

LNG is also still important in developed Europe, which famously saw a surge in coal burning after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—a surge that’s since declined due in part to the fuel being displaced by LNG.

U.S. LNG might have additional environmental benefits where it displaces natural gas supplies from countries, such as Russia or Qatar, that have fewer environmental regulations on gas production and transport (including on methane leakage) and whose state-owned producers are locked into much longer supply contracts (thus giving them more incentive to keep pumping out gas even after it stops making financial sense to do so). According to Bloomberg, in fact, the Biden administration announcement has some U.S. LNG customers nervously looking to Qatar and Russia for alternative supplies.

Finally, additional U.S. LNG exports might theoretically reduce domestic supplies and thus put some upward pressure on Americans’ natural gas bills (evidence there is mixed, but not significant either way), but any such higher prices would make renewable energy more price competitive and thus encourage its consumption here. You’d think the Biden administration would want that, given all the subsidies they’re tossing at wind, solar, and other renewables.

I guess you’d be wrong.

In short, reducing future U.S. LNG exports might cause global gas prices to rise and thus encourage the consumption of now-relatively cheaper renewables abroad. But it’ll do the exact same things to coal and biomass consumption, while also potentially encouraging the production and transport of relatively dirtier, more locked-in LNG from other sources. In the United States, meanwhile, captive gas supplies could—for a while at least—mean lower domestic natural gas prices, but that just means more U.S. gas consumption (and less consumption of the renewables that the Biden administration is so eagerly subsidizing). Overall, it’s a recipe for higher—not lower—carbon emissions in the future, along with all the other economic and geopolitical uncertainties.

Summing It All Up

Given these issues—and the LNG delay’s comically depressing backstory—it’s obvious to almost everyone (even many Biden supporters) that presidential campaign politics, not climate change, is driving the announcement.

If export approvals quickly resume after the November election and markets remain calm throughout, maybe it’ll in retrospect be considered a clever gamble. But if things do go south here, at least some of the blame should fall not on Joe Biden but on the law itself—a law that lets him and other self-interested politicians gamble on U.S. economic and national security with Americans’ property and livelihoods. Blame should also fall on multiple Congresses (ones run by Democrats and Republicans) for never reforming that law long after the United States was on its way to become a global energy powerhouse. Wonks (and not just me) had recognized the dangers of giving the president unlimited discretion to block energy exports on undefined “public interest” grounds, and numerous legislative proposals had been offered to make the system more automatic (e.g., like FTA-related shipments) and thus fix this obvious problem.

Of course, the perils of executive discretion and legislative inaction are hardly limited to the Natural Gas Act or Joe Biden. (Recall, for example, the law that the Trump-era Department of Justice said would let the president declare imported peanut butter a national security threat). Those laws need reform too, even if they’ve never been abused. That’s because, as last week’s LNG announcement and literally centuries of U.S. politics show, it’s only a matter of time before they are.

Chart(s) of the Week