Dear Capitolisters,

Big Tech’s Had a Rough Few Weeks. So Have Its Populist Critics.

Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter and other disruptions in the tech sector show how populist attacks are misguided.

One of the more telling (and depressing) shifts among folks on the right in recent years has been their populist attacks on “Big Tech,” which has become a sort of “get out of principles free” card for everything from speech to taxation to antitrust (but especially antitrust). As I’ve explained here repeatedly, I find this shift to be wrongheaded on substance and strategy—in large part (and in both cases) because of the dynamic nature of the U.S. tech sector. In short, it made little sense to me for right-leaning folks to abandon economically and ideologically sound principles (and to join fellow travelers on the populist left) to thwart today’s invincible corporate bogeymen because—given the long history of tech disruption—they’ll very likely be gone (or at least weakened) tomorrow.

Little did I know, however, how quickly events would prove my point.

Oh, Elon …

The biggest development in this regard is undoubtedly Elon Musk’s probable (we think?) acquisition of Twitter, which blunts several common populist shots at Big Tech. Most obviously, that an “unwoke” billionaire could—backed by a cadre of institutional and other investors—acquire a major social media company with the express objective of changing its “woke” policies and personnel shows that the good ol’ free market still can check “Big Tech” without government help. The alleged impossibility of such changes, in fact, was a core part of the new “conservative” argument for regulating Twitter, Facebook, Google, Amazon, and other tech companies allegedly biased against the right’s views: The brute force of government was required in this special case because “free markets” simply couldn’t solve the problem of ultra-powerful (and ultra-woke) tech giants. Things like “network effects” (the value users assign to a product because it has so many other users) and the uniformity of liberal thought in Silicon Valley, so the argument went, revealed libertarian arguments like “just build your own Twitter” to be laughably naïve. Drastic government action was therefore needed to address the (supposedly) grave, near-term threat that Big Tech presented.

Yet as numerous folks gleefully joked after Musk’s Twitter bid was accepted, instead of “build your own Twitter” we got “buy your own Twitter”—with very similar (promised, at least) results for the social media giant and its many conservative critics: departing “woke” employees, a more objective and transparent content moderation policy, fewer bots, dogs and cats living in harmony, and so on. Thus, there’s little reason to think today that other transactions in the tech space are somehow impossible, at least if there’s a good business case therefore. (In such cases, capital markets will be eager to help.) And, as we’ll see in the next section, the original “build your own” version of this argument may remain possible too. No special exceptions needed.

Musk’s Twitter acquisition also shows the potential perils of empowering government to attack Big Tech on ideological grounds. As we discussed last year, for example, moving from the relatively objective “consumer welfare” standard in U.S. antitrust law to a more subjective one that punishes “bigness” or “concentration” per se raises serious risks that regulators will use their newfound power and discretion to scrutinize or even thwart transactions that raise political, not economic, concerns. Maybe that’s not a problem when your team is in charge, but it can become one when you’re out of power—like, say, now for those Musk-cheering Republicans:

The U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is reviewing Tesla Chief Executive Elon Musk’s $44 billion takeover of Twitter Inc, Bloomberg News reported on Thursday, citing a person familiar with the deal. … The agency will decide in the next month whether it will do an in-depth antitrust probe of the proposed transaction, the person told Bloomberg. Such a probe would delay the deal’s closing by months.

Oops!

Now, look, it’s far from certain that the FTC will, in fact, open this investigation, but the risk is obviously higher in a world in which the agency is run by progressives unbound by the “consumer welfare” standard. Indeed, the former home of FTC chair (and “hipster antitrust” champion) Lina Khan is urging government intervention in the Musk-Twitter deal:

One critic of the deal has been Open Markets Institute, which said that it should be stopped to avoid giving an already powerful man “direct control over one of the world’s most important platforms for public communications and debate.” It also cited Musk’s ownership of the satellite communications company Starlink as a concern.

One must wonder how populist Republicans like Sen. Josh Hawley—who both cheered Musk’s acquisition and aligned himself with the trust-busting Open Markets Institute—are feeling these days, huh?

(No, I’m not laughing! Ok, maybe a little.)

Antitrust is the clearest recent policy shift challenged by the Musk-Twitter transaction, but there are surely others. For example, Republicans have become eager supporters of using expansive national security-related tools to thwart foreign investment in the American tech sector on vague or subjective grounds, eagerly supporting 2018 amendments to tools employed by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) to do just that. And with an eye on China (and reelection), President Trump used these and similar mechanisms to block several recent transactions, most famously demanding that TikTok’s Chinese owner divest from its U.S. operations. Trump and CFIUS also forced the Chinese owners of gay-dating app Grindr to sell the company because of concerns for users’ privacy, and blocked Singapore-based chipmaker Broadcom’s acquisition of U.S.-based Qualcomm out of vague China-related concerns. Now, experts openly wonder whether Musk’s Twitter acquisition will also face CFIUS review and related delays because several of his financial backers are foreign nationals or entities, and because of the TikTok, Broadcom, and other “precedent” set under Trump. The risk appears low, given that Musk is in control here, but it can’t be ruled out—and President Biden would have plenty of recent history (and a powerful new law shielding him/CFIUS from scrutiny) backing him up.

Tech’s Doing What Tech Does—Changing

The quick and radical changes to Twitter also provide another example of how quickly the market can change, and how this dynamism should temper folks’ regulatory enthusiasm. As we discussed last year, this is especially the case in tech, where today’s “unstoppable monopoly” is tomorrow’s struggling punchline. And, as Reason’s Peter Suderman first noted a couple weeks ago, this disruption is happening again—with predictable lessons for today’s anti-Big Tech crusaders:

Twitter is changing ownership, following a purchase by Elon Musk, who has explicitly said he intends to reorient the company’s approach to online speech. Netflix, whose business model has long been predicated on sky’s-the-limit growth, is bleeding subscribers. CNN+, a massively expensive project from what was once a dominant force in TV news, is shutting down a month after its launch. Facebook is losing regular users and taking a huge financial hit because of changes in the mobile ad space. Google is no longer the world’s most popular website.

If there is a single lesson to be learned here, it is that the marketplace for online communications, entertainment, and news media is never stable, and even the most powerful players can be dethroned.

All of these companies are still mighty. And yet they are all falling, or at least stumbling, in ways that the political class and its boosters assured us simply would not happen, because markets had become static, and competition was impossible. This notion—that the market has finally reached some sort of permanent equilibrium, in which certain companies will wield outsize influence over public life forever—has been used repeatedly to justify calls for regulatory interventions aimed at combating the power of big tech and media, on the premise that large corporations cannot be checked or dislodged by anything but government action. It’s a denial of dynamism. And what the recent spate of news makes clear is that this notion is wrong.

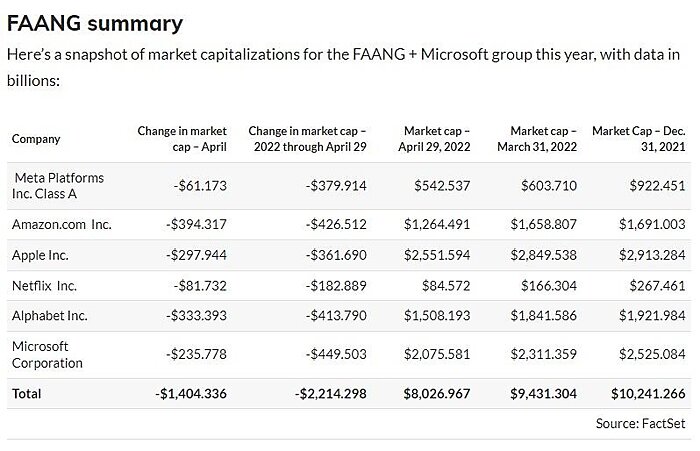

Since Suderman wrote that, the stock prices of the most powerful Big Tech companies have declined even further: The vaunted FAANGS + Microsoft lost $2.2 trillion in market capitalization between January and April alone:

A slightly different group of tech giants lost another $1 trillion in just three days in early May:

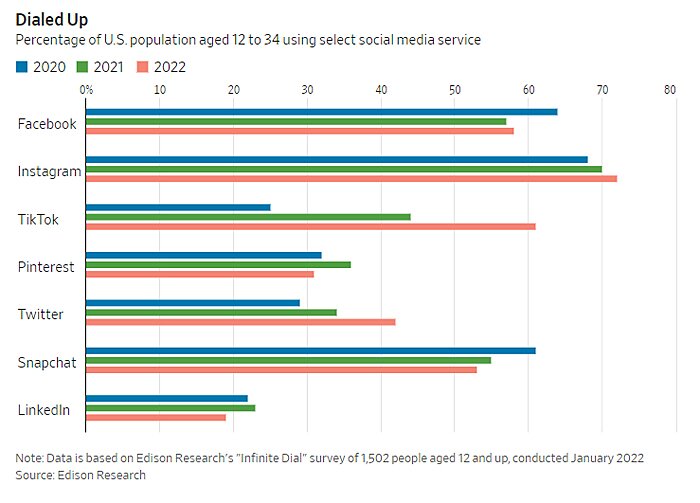

Meanwhile, TikTok officially knocked off Google and Facebook as the internet’s top-visited site last year and is killing it with young people, while other big players struggle:

The tech space also remains full of eager startups seeking to challenge tech’s biggest players, such as the cadre of social media apps looking to refine the social media experience:

“The era of a few big winners is ending,” said Eli Pariser, co-director of New Public, a nonprofit trying to create online spaces to foster healthy conversations. “Consumer tastes are changing. The one-size-fits-all approach—they’re seeing how much that’s breaking down.”

Overall, private investment in the American tech startups remains sky-high—and is “exploding” for companies working on applications for the decentralized “web3”.

That seemingly unstoppable tech behemoths are now rethinking staffing and watching a foreign rival assume the internet throne (for now) should cause a strategic reassessment from not only the investor class but the political class too.

But I’m not holding my breath.

Internal moves at some of these corporations—and not just at Twitter—may also be challenging the conventional wisdom about Big Tech and culture. Streaming giant Spotify, for example, has continued to resist calls that it deplatform controversial podcaster Joe Rogan. And Netflix just last week updated its website to note that employees may need to work on content they find objectionable—a clear corporate rebuke, following months of internal deliberations, of recent demands from lefty employees for more self-censorship. According to the memo:

Not everyone will like—or agree with—everything on our service. While every title is different, we approach them based on the same set of principles: we support the artistic expression of the creators we choose to work with; we program for a diversity of audiences and tastes; and we let viewers decide what’s appropriate for them, versus having Netflix censor specific artists or voices.

As employees we support the principle that Netflix offers a diversity of stories, even if we find some titles counter to our own personal values. Depending on your role, you may need to work on titles you perceive to be harmful. If you’d find it hard to support our content breadth, Netflix may not be the best place for you.

The message in both cases is that consumer demand, not a vocal minority’s cultural hobbyhorses, will dictate corporate decision-making. As The Bulwark’s Sonny Bunch just noted about Netflix:

Regardless, Chappelle is irreplaceable at Netflix. There’s simply no one else like him. Programmers and flacks and executives, on the other hand? Dime a dozen. We’ll see if they have the courage of their convictions to hit the road in response.

The market, it seems, might still work after all. Go figure.

Changing Minds?

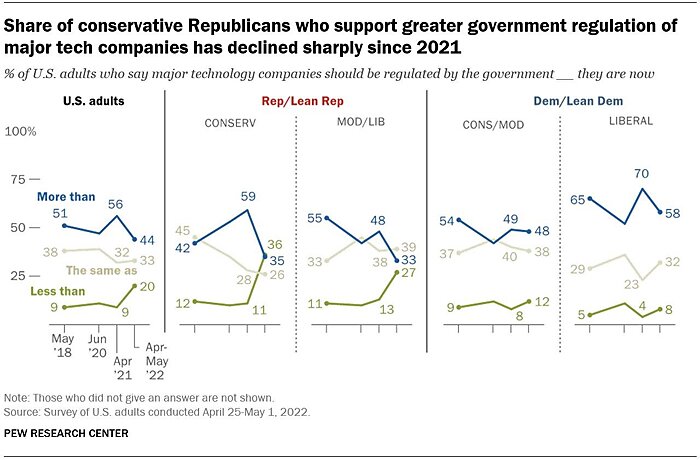

None of this is to say, of course, that there aren’t still a lot of libs in tech, that Facebook and Google are disappearing tomorrow, or that companies won’t still dip their toes in the culture wars for commercial or social reasons. (Texas-based and Musk-owned Tesla, after all, just updated its corporate policies to pay for employees’ out-of-state, ahem, medical procedures.) But the last few months have undeniably challenged the alleged inevitability of Big Tech commercial and cultural dominance, and it appears voters—especially but not only conservative ones—are starting to notice:

That views on Big Tech regulation could change so quickly is a timely reminder that one of the only things more ephemeral than tech supremacy is public opinion—a lesson that may have been useful before conservatives ditched their principles.

[Capitolism will be off next week.]

Chart(s) of the Week

The Links

“Globalization nowadays may be a dirty word, but having diverse suppliers is an economic strength” (related)

Amazon’s recruiting (and paying) mom-and-pop stores in rural America

Solar tariffs are a giant mess

Please stop invoking the Defense Production Act

“Biden’s No-Show on Trade Deals Risks Isolating Friends in Asia”

Some historical perspective on U.S. housing affordability

Anti-automation solidarity at American ports

Immigrants are coming back to the U.S. labor market

Prosperity: Russia on track for a record trade surplus

Debunking the “Greedflation” conspiracy theory

The U.S. has a refinery problem

NY congressional candidate runs on a Jones Act/tariff reform platform

“Because of WIC’s scale, its exclusive statewide contracts encourage consolidation”