Dear Capitolisters,

An increasingly common tactic on the populist right is to label skeptics of new government programs (protectionism, subsidies, etc.) “free market fundamentalists” who dogmatically oppose any and all government regulation and believe in the perfection of free markets (or whatever). The ploy is hardly new—Wikipedia (citing the U.N.!) notes that the term is a common pejorative that’s been employed by pro-“interventionist” lefties like Joseph Stiglitz, Paul Krugman, and George Soros—but it’s recently become the go-to label for many on the nationalist right who have long championed protectionist and other market-skeptical policies or who see the Rise of Trump as their golden ticket to political power and, perhaps, even riches. Indeed, one can hardly read an op-ed by or article about these up-and-coming policy entrepreneurs without encountering some form of “market fundamentalist” rhetoric, which is used to quickly brush aside any and all criticism of populist policy as religious zealotry unworthy of serious consideration (and, of course, the cause of all of our current economic and political problems, be they real or imagined).

The tactic, I must admit, has proved successful in the media, likely because it confirms the market-skeptical views of many journalists and editors (and the left-leaning experts they routinely publish). However, the “market fundamentalist” pejorative ignores several essential facts that reveal its baselessness. First, few, if any, serious libertarian or conservative critics of populism actually oppose all forms of government intervention in the economy. Instead, they (we) are skeptical of incessant allegations of pervasive “market failures” and of the government’s (politicians’) ability to fix those that truly exist. Where those two tests are met, they (we) readily concede government intervention may be appropriate or even necessary. (See, for example, Russ Roberts’ discussion here, Michael Munger here, or this one from me on libertarianism in a pandemic.)

Second, criticism of populist interventionism is not based on blind faith or ideology—though I freely admit a natural bias toward liberty—but instead on a vast repository of evidence showing that we should be strongly biased in favor of economic freedom and against populist economics, which not only make us poorer but create the economic conditions that can breed more (and worse) populist policies in the future.

So today we’ll review some of that evidence, and why we so eagerly work to break the Populist Feedback Loop.

Populism Produces Lower Growth and … More Populism

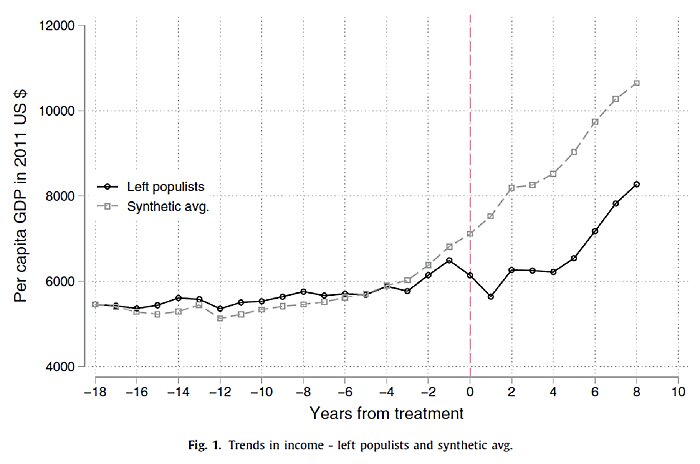

Numerous academic papers have found that populist policies and leaders produce lower economic growth and living standards. For example, a 2020 examination of left-wing populist leaders in Latin America found that their governments “have, on average, a negative, significant, and sizeable average effect on income.” In particular, countries that concentrate power in their executive branches and enact “anti-market economic policies” ended up more than 20 percent poorer on average than what a reasonable, market-oriented alternative (“synthetic”) would have predicted:

Meanwhile, the authors found no significant countervailing tradeoff “in decreased levels of income inequality or infant mortality.” So this populism is all pain, no gain.

Such results are not, however, limited to left-wing populism. A 2020 paper from the Center for Economic Policy Research examined 60 countries representing 95 percent of world GDP between 1900 and 2018 to find leaders engaged in “populism,” which they define as “a political style centered on the supposed struggle of ‘people vs. the establishment’” with presidents or prime ministers that “place the narrative of ‘people vs. elites’ at the center of their political agenda and then claim to be the sole representative of ‘the people.’” (Sound familiar?) This approach yielded a dataset of 50 “populist” leaders, on the left and the right, and miserable economic results:

Over 15 years, GDP per capita and consumption decline by more than 10% compared to a plausible non-populist counterfactual. Moreover, despite their claim to pursue the interests of the ‘common people’ against the elites, the income distribution does not improve on average. We find robust patterns in the data that link the economic stagnation under populists to economic nationalism and protectionist policies, unsustainable macroeconomic policies, and the erosion of institutions, checks and balances, and legal protections.”

These economic effects, the authors find, “do lasting damage to the economy.” They also find strong evidence of the Populist Feedback Loop: Populists often enter office after periods of economic decline (e.g., recessions), and countries that had a populist leader once “have a significant higher likelihood of seeing another populist coming to power.” In other words, populist policies produce the economic conditions that make people clamor for… more populism. Rinse, repeat.

It’s therefore not merely “faith” or “ideology” that drives me and others to be so intensely skeptical of populism as a sound governing and economic approach. Whether it’s tariffs, local content rules, subsidies, or other “anti-market” policies, the data show—on the macro level and with respect to specific policies (e.g., trade)—populism has earned the intense skepticism it receives.

Economic Freedom Lifts All Boats

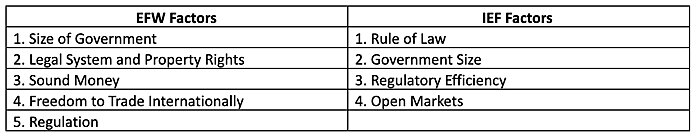

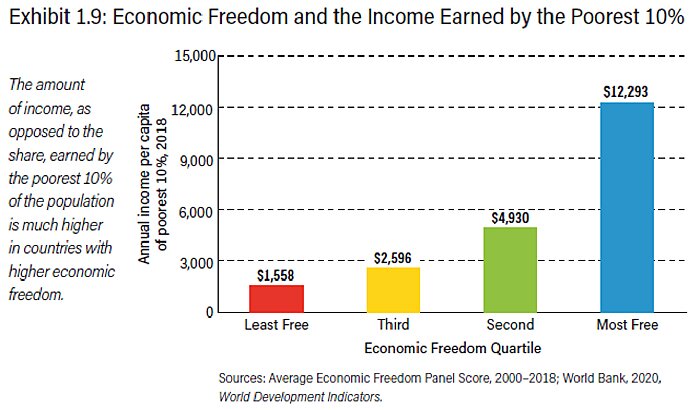

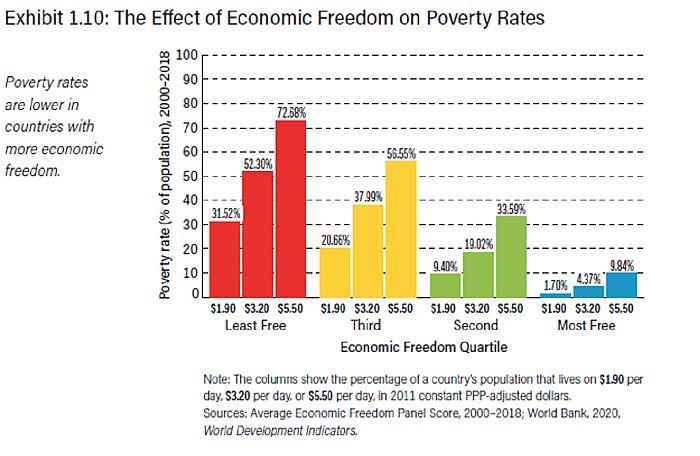

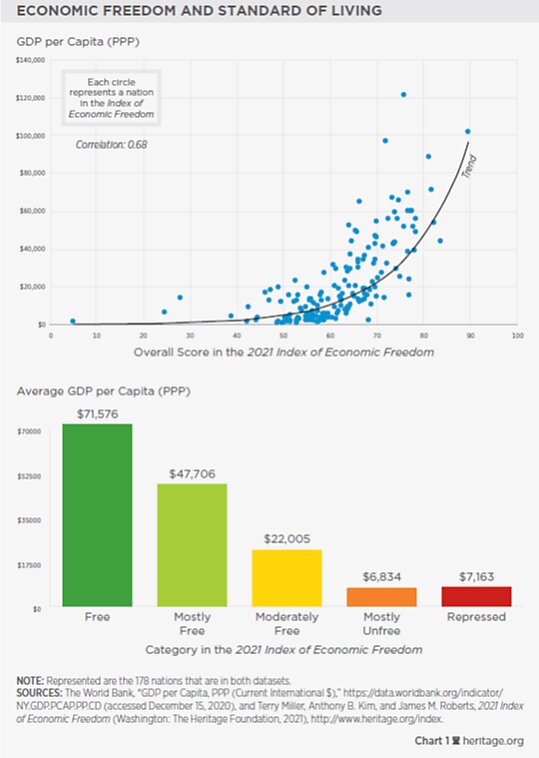

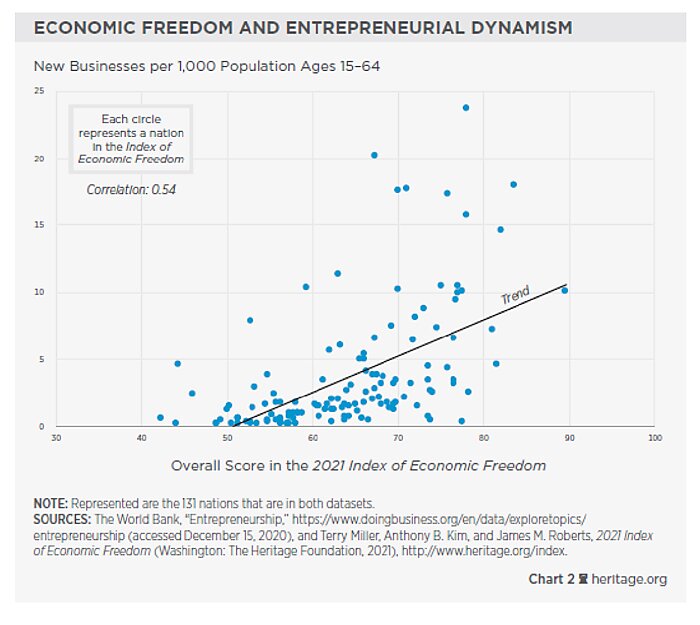

At the same time, ample evidence shows that economic freedom and limited government are strong determinants of prosperity, and that—contra the populist narrative—these gains are broadly (though certainly imperfectly) shared. For starters, the two most common annual assessments—the Fraser/Cato Economic Freedom of the World and the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, which have each been around for decades—show a strong relationship between “economic freedom” and various measures of well-being. The reports’ definitions of “economic freedom” vary a bit, but each examines the same general factors:

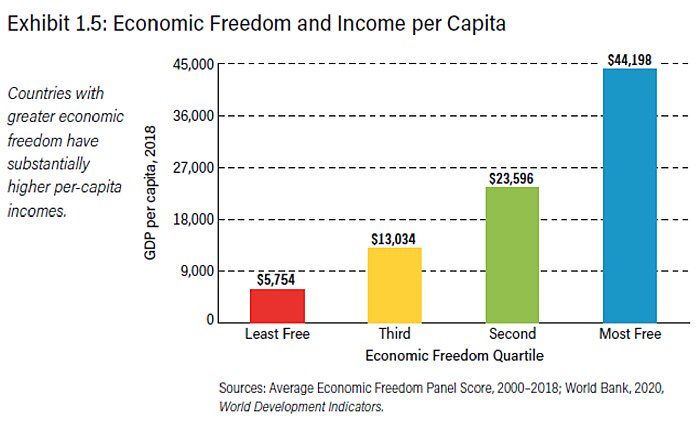

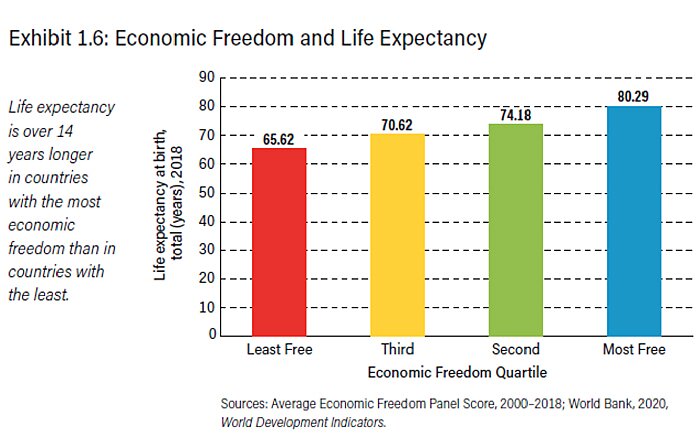

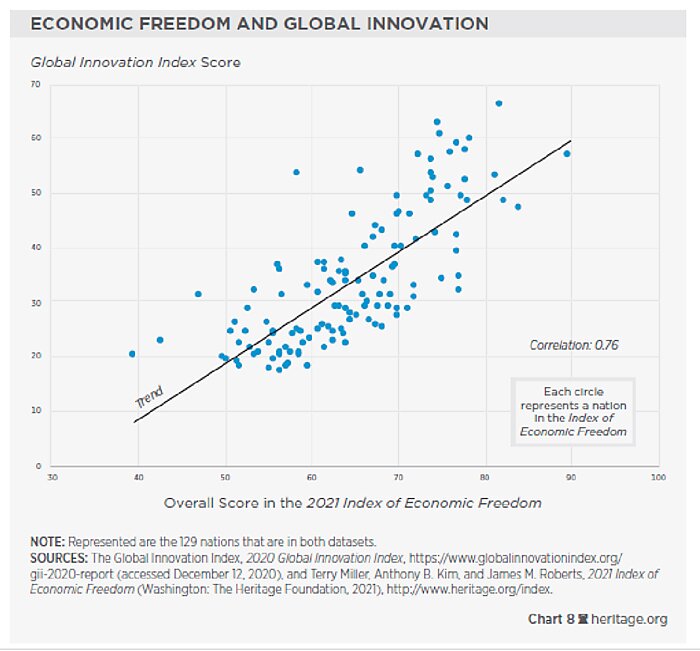

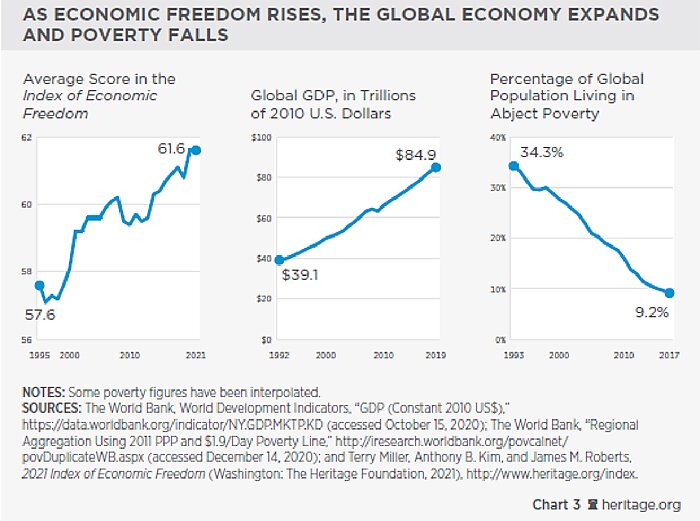

By applying the same standards over long periods, the studies’ authors can assess not only how countries’ policies evolve over time but also the broader relationship between “economic freedom” and economic performance across countries. And on the latter, each comes to the same general conclusion: More economic freedom means more prosperity, and nations that are economically freer outperform less-free nations across various indicators of well-being, such as per capita GDP, average incomes, poverty, life expectancy and infant mortality, gender equality, environmental performance, innovation, democratic governance, and social progress. Feel free to click through each report for yourself, but here are a few examples from the latest EWF report:

And from latest IEF report:

Various academic work has used these rankings to draw similar conclusions about the relationship between economic freedom and prosperity. Summarizing that work related to the EFW, a 2013 paper concluded:

Of 402 articles citing the EFW index, 198 used the index as an independent variable in an empirical study. Over two‐thirds of these studies found economic freedom to correspond to a “good” outcome such as faster growth, better living standards, more happiness, etc. Less than 4% of the sample found economic freedom to be associated with a “bad” outcome such as increased income inequality. The balance of evidence is overwhelming that economic freedom corresponds with a wide variety of positive outcomes with almost no negative tradeoffs.

Other studies have found a causal connection, at least in part, between economic freedom and economic growth. For example, a brand new paper from economists Kevin and Robin Grier found that the 49 countries with a sustained (five-year) improvement in EFW score between 1970 and 2014 experienced a 16 percent improvement in real GDP per capita after 10 years, as compared to other EFW countries. Economists have also found that specific reforms to increase economic freedom improved companies’ productivity (thus contributing to faster growth).

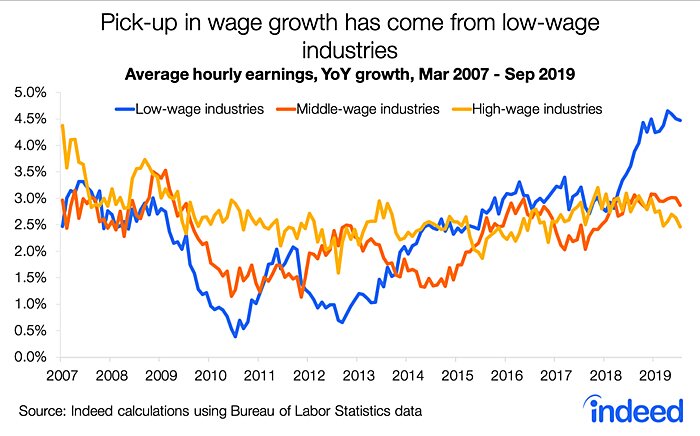

Contrary to some populist critics, moreover, economic growth is still crucially important for American workers and living standards. Research shows, for example, that wage growth—especially for workers at the bottom of the ladder—tends to occur when the economy is strong. And this connection continued during the Trump years, which AEI’s Michael Strain noted in 2018 was “visible proof that the hot U.S. economy is the best jobs program available for lower-wage and vulnerable workers”:

The unemployment rate for the least-skilled workers is outperforming its average to a greater extent than for higher-skilled workers. Earnings are growing significantly faster for workers without a high school diploma than for higher-educated workers. The rate of employment among workers with a disability has jumped 26 percent in the last six years. The formerly incarcerated seem to be having a much easier time in the workforce than in previous years, and employers are less likely to require background checks on job applications.

Growth doesn’t just help low-income and working-class households in the short term. Over longer periods, seemingly small changes in the growth rate have large consequences. In the past four decades, for example, real GDP per person has increased from about $28,000 to over $55,000, growing at about 1.7 percent per year. If growth instead had been 1 percent, average GDP per head would be about three-quarters what it is today.

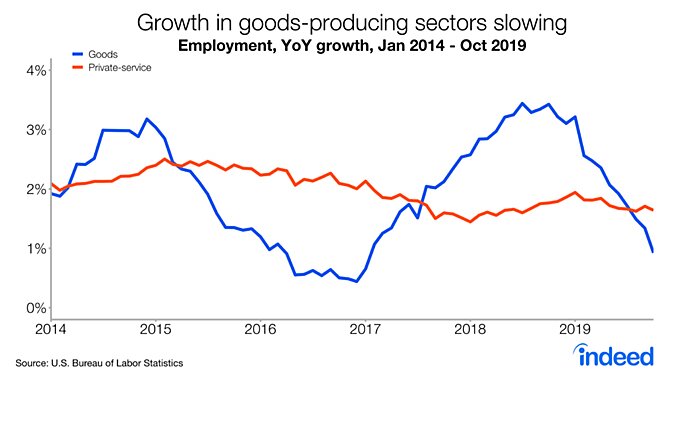

Those trends continued until the pandemic hit, while also revealing the limitations of populist interventionism. In fact, the initiation of various trade wars in 2018 coincided with slowing job/wage growth in the very sector that Trump was supposedly trying to help (manufacturing), while faster U.S. wage growth was concentrated in low-wage jobs, which are almost entirely services (retail, leisure/hospitality, etc.):

And as we’ve already discussed, numerous studies showed that Trump’s populist tariffs actually harmed manufacturing growth and investment. (There’s also little to suggest that Trump’s immigration restrictions boosted low-skill jobs and wages in 2018–19, especially given their scope and timing.)

These trends confirm recent research about how economic freedom affects income inequality—a constant lament of growth skeptics. In particular, a new examination of 145 countries in the EFW index found that “reforms that increase economic freedom will boost medium-run growth for all five income quintiles. In other words, economic freedom does seem to lift all boats.” (Emphasis mine.) The authors find that two factors—institutional quality (rule of law, protection of property rights, etc.) and policy quality (monetary, trade, and regulatory liberalization)—improve all groups’ incomes under all types of governments, while limited government does the same for democracies (but not necessarily for autocratic societies). This is consistent with other research that shows a strong connection between average incomes (which could in theory reflect a society of very rich and very poor people) and median ones (which reflect the midpoint of all earners).

Finally, certain policies seem to be “leaders” in terms of presaging improvements (or declines) in economic freedom and the resulting improvements (and declines) in living standards. In examining changes in a country’s EFW ranking, a 2017 paper found that:

Government policies related to the freedom to trade internationally in capital and goods seem to be the clearest and most robust ‘first mover’ in cases of significant institutional reform, both upward and downward. It is also the largest contributor to the magnitude of the overall ending reform. This is consistent with the arguments made by Coyne (2008), Leeson et al. (2012), and Sobel and Leeson (2007) regarding the role of free trade in initiating and spreading positive institutional reform, as well as the correlation present in the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act preceding the onset of the New Deal programs in the United States during the early 20th century (and the more recent decline in the U.S. institutional rank over the past two decades).

This conclusion not only echoes Milton Friedman’s observation that protectionism is a gateway drug to bigger, badder economic interventions, but also helps to explain why trade can serve as a pretty good litmus test for predicting politicians’ and wonks’ real-world support for free market policies in the future. It’s the canary in the coal mine.

Summing It All Up

Given the evidence above (and plenty more), it’s thus quite reasonable—and certainly not “fundamentalist”—to adopt a strong presumption in favor of economic freedom and equally strong skepticism of populist economics, while acknowledging that specific deviations from these views may indeed be warranted based on the specific issue at hand. Determining precisely when to deviate from these defaults requires a thoughtful examination of the alleged problem and its proposed solution, based on the facts, history, law, and economics at issue. In particular, we should demand hard proof of alleged market failures (as opposed to, for example, distortions caused by other government policies) and of the government’s ability to produce a better outcome than the imperfect one that the market already provided. That’s no easy hurdle—nor should it be, given the stakes and the all-too-real risk of creating economic conditions that breed even worse policy (and policymakers) in the future.

It seems that even many populists understand these risks—or at least understand that their voters do. Frequently, the same folks brushing aside us “market fundamentalists” are quick to add that they, of course, still support free markets generally but are compelled to make an exception in the case of whatever policy they may be advocating at the moment (almost always without meeting the two-proged standard above). Yet those “exceptions” seem to be multiplying by the day—moving from the “standard” populist ones for trade and immigration to exceptions for industrial policy, capital markets, antitrust and Big Tech, family policy, minimum wages, corporate taxation and governance, and so on. At some point, the anti-market exceptions will swallow the pro-market rule, and no amount of “fundamentalist” finger-wagging will change that fact.

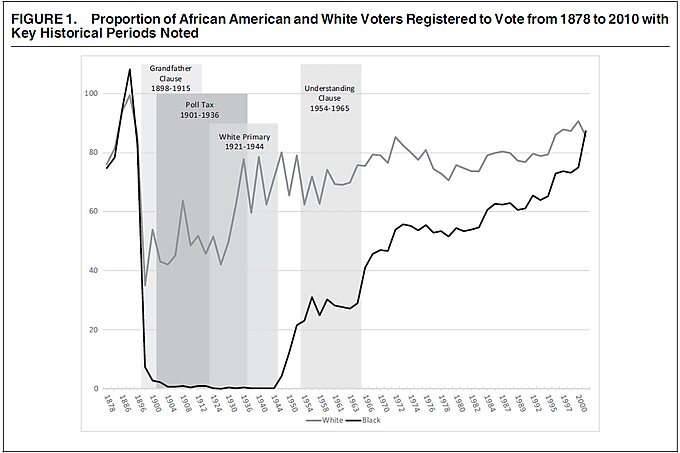

Chart of the Week

Just how much Jim Crow laws disenfranchised black Louisianans (source):

The Links

My new paper with Inu Manak on Section 232 (plus a podcast on national security)

Boeing-Airbus tariffs suspended; American wine drinkers rejoice (Scotch too)

“Trump’s Protectionist Failure”

When Amazon (and Walmart and Target) raises wages, local companies follow

For-profit startup fixes governments’ “leftover vaccine” problem

“Why China Worries about Losing Manufacturing”

China’s bureaucracy problem is a problem

Time for another rare earths panic!

How to really compete with China

Ford’s “quietly” moving some small truck production to Mexico

“Soaring home prices are starting to alarm policymakers”

How to define and measure “food insecurity”

The IRS takes on a brilliant credit card points strategy

Are landlords “warehousing” vacant units due to the eviction moratoria?