In case you haven’t noticed, antitrust is having a moment. Over the last few months, the Biden administration has stocked the executive branch with appointees who support far more vigorous enforcement of U.S. antitrust laws—primarily the Sherman Act of 1890, the Clayton Act of 1914, and the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914. Several new antitrust bills are floating around Congress to give these and other statutes more teeth, and just last week, Biden’s new FTC chairwoman, Lina Khan, announced an agency vote this Thursday on whether to rescind a 2015 policy statement regarding the FTC’s regulation of “unfair methods of competition” under Section 5 of the FTC Act.

That statement required the agency to emphasize the “promotion of consumer welfare” and “business justifications” and thus essentially limited FTC enforcement actions to those issues. So, for example, the FTC would routinely seek to prevent two large rivals (e.g., two hospital systems in Idaho) from merging, arguing that the new, merged entity would have market power to demand higher, above-market prices for area consumers.

Given the 3–2 Democrat majority among the FTC’s commissioners, the 2015 policy’s recission and more expansive antitrust enforcement—away from the “consumer welfare standard” that has guided U.S. antitrust enforcement for decades towards one that punishes “bigness” per se—is likely. A couple of those bills are also expected to become law, as even some Republicans—traditionally skeptical of antitrust—are converts, following the Trump administration’s late-term epiphany on (and action against) “Big Tech.”

One of those actions, against Facebook, took a big hit on Monday when a federal judge ruled the Trump administration’s claim that Facebook was a monopoly to be essentially baseless. That won’t stop the antitrust train in Washington, but it might slow it down a little. And that, quite frankly, is a good thing for at least three reasons—reasons that should give us pause about a more vigorous U.S. antitrust policy.

Failure to Grasp Market Dynamism

Perhaps the biggest reason to be skeptical of government attempts to break up dominant companies is that the market—not the state—has routinely eliminated those companies’ dominance only a few years after antitrust advocates deemed them to be unstoppable “monopolies.” This “creative destruction”—as first coined by economist Joseph Schumpeter in 1942—is particularly evident in the technology sector, which has rapidly evolved over the last 100 years, but it’s definitely not limited to tech. My Cato colleague Ryan Bourne documented several of these cases in a highly entertaining 2019 paper arguing against the trendy fatalist view that companies’ current market dominance will inevitably persist, undermining consumer welfare in the process:

Schumpeter warned against such monopoly fatalism. He recognized that the most important long‐term competitive pressure comes from new products cannibalizing incumbent businesses through marked product quality improvements. An antitrust policy that second‐guesses the future based on the present ignores this unpredictable margin of competition, to the detriment of consumers.

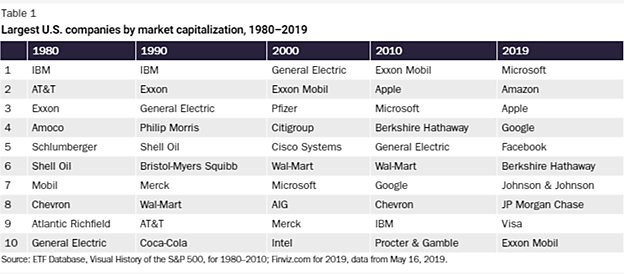

A simple examination of the largest U.S. companies since 1980 shows creative destruction at work, constantly challenging and changing the top dogs:

Bourne goes on to detail numerous instances in which supposed “monopolies” targeted by antitrust advocates were here today and gone tomorrow, including:

-

The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P), which rose to dominate the grocery business in the 1920s and 30s, was challenged by big-box supermarkets in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and finally declared bankruptcy (twice) last decade.

-

Kodak, which in 1976 “was estimated to have 90 percent of the U.S. film market and 85 percent of the market for cameras,” and filed for bankruptcy in 2012. Today, it’s trying to reinvent itself—again—as a (state-subsidized) pharmaceutical company.

-

Netscape, which dominated web browsing in the mid-1990s, yet was put out to pasture by 2003. It was crushed, of course, by Microsoft’s Internet Explorer—itself the subject of antitrust scrutiny (and deemed an unstoppable monopoly) in the early-2000s, right as new competitors like Firefox and Safari were emerging to replace it.

-

Myspace, which controlled early social media in the 2000s—leading to the hilarious-in-retrospect 2007 headline “Will Myspace ever lose its monopoly?” in the Guardian (of course)—and is today a punchline. As Bourne notes, Myspace’s demise is a strong counter to current claims that Facebook and others’ “network effects” make them unstoppable: “The time invested in uploading content, coupled with the utility of the product rising with the number of users on the network, supposedly made Myspace’s dominant position unassailable.” Not so much.

-

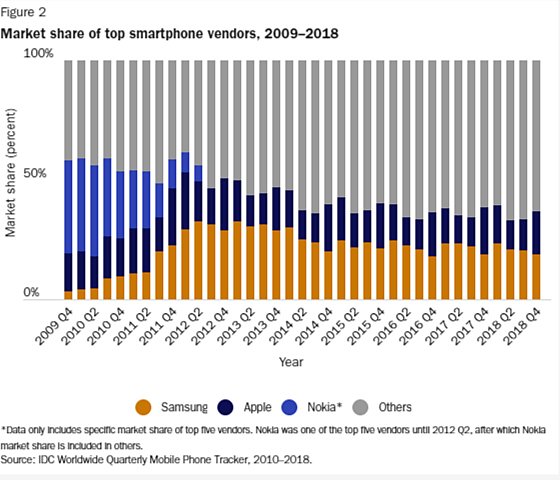

Nokia, which was a “mobile monopoly” in 2007 and 2008—right before the iPhone came out:

-

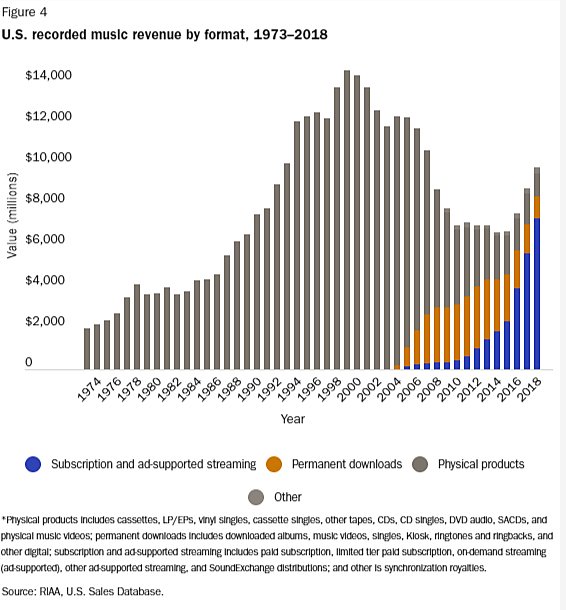

iTunes, which dominated digital music sales (and faced a French antitrust suit) in 2010, yet was by that time already being disrupted by streaming services like Pandora and Spotify—a model that today dominates but is also thick with competition (including copycat Apple Music).

These examples are just the tip of the iceberg. Others include, per Bourne, Xerox, Yahoo!, AOL, and IBM (“the subject of a 13‐year antitrust lawsuit that was ultimately dismissed “without merit” in 1982” and also investigated in the 1970s for monopolizing the—I kid you not—office typewriter industry). More recently, there’s the now-laughable Staples-Office Depot merger that the FTC blocked in 2016, but perhaps my two favorite other examples are Blockbuster Video:

And Toys R Us:

“Federal antitrust enforcers are investigating whether Toys “R” Us Inc. used its market clout to stifle discounting by retail competitors and force consumers to pay higher prices for baby products.“https://t.co/jQEm7bftKr pic.twitter.com/oKZnizNzC9

— Scott Lincicome (@scottlincicome) September 20, 2020

The list goes on and onand on. Maybe, as antitrust advocates commonly claim, this time really is different, but—given the long history of Schumpeterian creative destruction unexpectedly leveling once-dominant firms—it probably isn’t (and signs are already emerging along those very lines).

The bar for new government action should thus remain high, not be lowered as many in Congress and the Biden administration are now trying to do.

Abuse by Competitors and the State

Beyond the theory, antitrust skepticism is also warranted from its practice. In particular, there is a long and ignominious history of U.S. antitrust laws being abused by both private parties (whom the law empowers to challenge competitor companies’ anticompetitive behavior) and the government itself.

Northwestern’s Fred McChesney summarized the former issue several years ago:

One of the most worrisome statistics in antitrust is that for every case brought by government, private plaintiffs bring ten. The majority of cases are filed to hinder, not help, competition. According to Steven Salop, formerly an antitrust official in the Carter administration, and Lawrence J. White, an economist at New York University, most private antitrust actions are filed by members of one of two groups. The most numerous private actions are brought by parties who are in a vertical arrangement with the defendant (e.g., dealers or franchisees) and who therefore are unlikely to have suffered from any truly anticompetitive offense. Usually, such cases are attempts to convert simple contract disputes (compensable by ordinary damages) into triple-damage payoffs under the Clayton Act.

The second most frequent private case is that brought by competitors. Because competitors are hurt only when a rival is acting procompetitively by increasing its sales and decreasing its price, the desire to hobble the defendant’s efficient practices must motivate at least some antitrust suits by competitors. Thus, case statistics suggest that the anticompetitive costs from “abuse of antitrust,” as New York University economists William Baumol and Janusz Ordover (1985) referred to it, may actually exceed any procompetitive benefits of antitrust laws.

In a 2004 piece, Preston McAffee and Nicholas Vakkur document that private litigation has been used as a tool for “harassing, harming and exporting payments” from other firms in at least seven distinct ways—each of which is unrelated to the public goal of promoting healthy market competition.

-

Extort funds from a successful rival.

-

Change the terms of a contract.

-

Punish non-cooperative behavior.

-

Respond to an existing lawsuit.

-

Prevent a hostile takeover.

-

Discourage the entry of a rival.

-

Prevent a successful firm from competing vigorously.

They cite examples of each such “strategic action” and document how these cases did nothing but enrich the plaintiffs at the defendants’ expense. And, as they note, the law itself permits such abuse because it tilts the playing field heavily against defendant companies:

The potential for antitrust laws to be misused exists because antitrust cases are complicated and expensive to defend. Much of the behavior proscribed by the antitrust laws is subject to the “rule of reason,” in which a class of behavior is illegal if it doesn‘t have a pro-competitive explanation. … Consequently, defendants in antitrust suits can be compelled to provide explanations and analysis of their behavior, produce a mountain of documents sometimes running into the tens of millions of pages, and have their executives spend days or even weeks in depositions and preparation for deposition.

Private lawsuits have declined in recent years, but companies can also try to hurt their competitors by aiding government investigations, as Oracle did during the Microsoft case. Also, private suits may be making a comeback. For example, just this year several publishers, including The Daily Mail, have filed antitrust suits against Google and Facebook (who compete with those same publishers for ad dollars and also sell them ad services) for supposedly manipulating search results to steer users away from their websites. Several farmers have filed antitrust suits against “big ag” companies for colluding to prevent seed and fertilizer price transparency on certain e‑commerce sites. I won’t guess as to the merits of these cases, but they seem to track the McAffee/Vakkur framework and—regardless—show that private antitrust actions, which have a history of abuse, aren’t a relic of a bygone era.

Private companies, moreover, aren’t the only potential abusers of antitrust law. As McChesney notes, several studies have shown that “patterns of antitrust enforcement are motivated at least in part by political pressures unrelated to aggregate economic welfare.” This includes not only politicians’ efforts to stop mergers that would close plants or outsource jobs in their home districts, but also more nefarious objectives. As former FTC chief economist Jonathan Baker documents, for example:

Lyndon Johnson held up the antitrust review of a bank acquisition until a newspaper publisher, who also ran one of the merging banks, agreed to reverse the paper’s editorial position against him. President Nixon ordered the Justice Department not to appeal a lost court challenge to a merger by International Telephone & Telegraph, allegedly in exchange for a substantial contribution by ITT to the Republican National Convention. Nixon also threatened three major television networks with antitrust lawsuits in an effort to extract better news coverage and allegedly accepted a campaign contribution from Howard Hughes in exchange for withholding an antitrust challenge to a planned Las Vegas hotel acquisition.

In June of last year, moreover, DOJ whistleblower John Elias testified before the House Judiciary Committee that the Trump administration’s Antitrust Division investigated 10 cannabis industry mergers—subjecting them to intense scrutiny (at considerable cost yet with no official enforcement actions taken)—simply because Attorney General Bill Barr “did not like the nature of their underlying business.” Elias also claimed that the Antitrust Division’s political leadership initiated another investigation—of an emissions agreement between several automakers and the state of California — after Trump angrily tweeted about the deal, disregarding standard process for determining whether to open and publicize a case.

Then, of course, there are recent antitrust actions against Facebook from both the right and the left, neither of which—as the preceding links show—appear to be well-grounded in economics or law (but have plenty of political support). As noted at the outset, at least one federal judge now seems to agree, sending the FTC back to the drawing board because it’s case against Facebook lacked “any indication of the metric(s) or method(s) it used to calculate Facebook’s market share” (which is kinda the whole point in an antitrust case!). And there’s Ted Cruz and colleagues threatening antitrust action against Major League Baseball on express political grounds, or recent indications that Democrats’ new “Big Tech” legislation has been modified to exempt Microsoft.

Surely, not every antitrust action that the government threatens or files has such seedy political origins, but these and other cases again should give us pause before diving headlong into a deep pool of new interventions. And they’re a big reason why many economists believe that, overall, the costs of antitrust enforcement outweighs any benefits.

Failure to Consider State-Sanctioned Anti-Competitive Behavior

Finally, my skepticism of expanded antitrust policy stems from many advocates’ failure to acknowledge—or outright advocacy for—several types of anticompetitive actions sanctioned by the state itself. The most obvious example, of course, is the U.S. Postal Service, which not only has a legal monopoly on the delivery of first-class and standard mail (as well as on access to mailboxes), but also benefits from all sorts of other state subsidies, exemptions, and powers that discourage competition.

One doesn’t need, however, a legislated monopoly to engage in anti-competitive and anti-consumer behavior sanctioned by the government. The Capper-Volstead Act, for example, specifically exempts agricultural cooperatives from antitrust scrutiny (thus letting farmers collude to set output levels and prices) and has become a particular problem in the U.S. dairy industry: “As a result, dairy cooperatives have experienced unfettered and unregulated growth and now manage the milk supply and control almost every aspect of production from cow to grocery store.”

U.S. trade law, moreover, allows domestic companies and workers—even direct competitors—to petition the government to block imports of a product and thus raise its price (at consumers’ expense). Never mind that research shows how imports counteract domestic industry concentration and thus benefit American consumers —something even eager Big Tech trustbusters like Sen. Josh Hawley seem to understand when his constituents are being harmed by protectionism. This situation is particularly egregious in the case of the anti-dumping law, which polices “unfair” trade in the form of imports that are simply priced too low (without any actual evidence of predatory behavior by the foreign companies). And why can U.S. companies collude in this anti-consumer way? Because U.S. law—the Noerr-Pennington doctrine—especially exempts such actions from antitrust scrutiny.

To paraphrase Nobel Laureate Ronald Coase: When prices are too high, the government yells “monopoly”; when prices are too low, the government yells “dumping”; and when prices all stay the same, the government yells “collusion.” It’s frustrating to say the least.

But it’s not just trade or agriculture policy that’s infected with such state-empowered problems. As we discussed in December, “a cabal of building contractors, building craft unions, building code inspectors, architects, materials producers and politicians—primarily the National Association of Homebuilders (NAHB) and the U.S. department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)—successfully worked in the 1970s to block the rapid growth of higher-productivity, lower-price factory housing in the United States.” This anti-competitive situation and many others are documented in a series of papers for the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank by economist James Schmitz Jr. Beyond housing, he finds politically powerful “monopolies” (technically, they’re more like cartels) that lobby for and benefit from laws and regulations that “raise the prices for their goods [and] simultaneously destroy substitutes for their products, low-cost substitutes that are purchased by low-income households.” This includes legal services, oral health services, hearing aids, eyecare and eyeglasses, financial services, and K‑12 public education. The Obama and Trump FTCs started to push back on some of this, targeting the anti-competitive practices of state regulatory boards controlled by the same “market participants” (e.g., dentists) they regulate, and the Supreme Court upheld these actions in 2015. But the ruling is limited; there’s far more work to be done; yet few of today’s modern trustbusters seem interested in doing it.

That’s a shame, as I’d be much more willing to take their concerns seriously if they went after the anti-competitive practices facilitated by law with the same zeal as they do the ones supposedly plaguing the “free market.”

How to Really Boost Competition

So if more vigorous antitrust enforcement isn’t the answer (or, at the very least, should be pursued with extreme humility and caution), what, if anything, should government do to boost competition and entrepreneurship in the United States? Well, the obvious place to start is by reforming or eliminating the laws and regulations expressly intended to diminish market competition—especially in the areas already documented to be suffering from high prices, diminished consumer choice, and limited competition. As my Cato colleague Bob Levy once said:

Barriers to entry are created by government, not private businesses. When a company advertises, lowers prices, improves quality, adds features or offers better service, it discourages rivals. But it cannot bar them from the marketplace. True barriers arise from government misbehavior, not private power — misbehavior like special‐interest legislation or a misconceived regulatory regimen that protects existing producers from competition. Instead of using antitrust laws to limit the aggressiveness of incumbent firms, the government should do away with the barriers it erected that keep competitive newcomers from entering the marketplace.

As far as particular reforms go, we can start with the ones Schmitz documented, as well as the “never needed” regulations that governments temporarily suspended during the pandemic to boost their economies and help manufacturers, healthcare providers, and other industries get through the downturn. As the Wall Street Journal noted in April, many states are considering whether to make these suspensions permanent, so there’s already momentum here. Beyond that low-hanging fruit, Chris Edwards (another Cato colleague) has done yeoman’s work in a new paper documenting many state and local regulations that discourage startups and innovation. This includes “certificate of need” rules (which require that entrants to certain industries receive government approval), occupational licensing (which we discussed here in December), wage and benefit mandates, and bans on certain products or their distribution (hemp, raw milk, certain types of alcohol, etc.). I’d also be remiss not to mention the need for common-sense reforms to U.S. trade law, which currently bars investigating agencies from even considering consumer harms when deciding whether to impose new import restrictions. And in Big Tech’s particular case, it’s essential—as we’ve also discussed—to keep the meat of “Section 230” in place to help small internet start-ups and their investors avoid costly lawsuits (or the threat thereof).

In short, there’s plenty of stuff for policymakers to do (and, in 230’s case, not do) to boost competition and help American consumers, without the many drawbacks of new and expanded antitrust action. It’s (unfortunately) telling that few in Washington are willing to look.

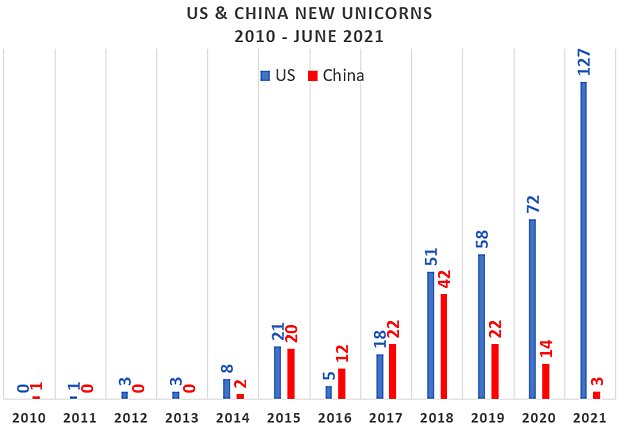

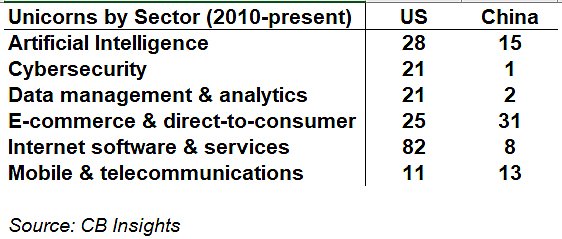

Chart(s) of the Week

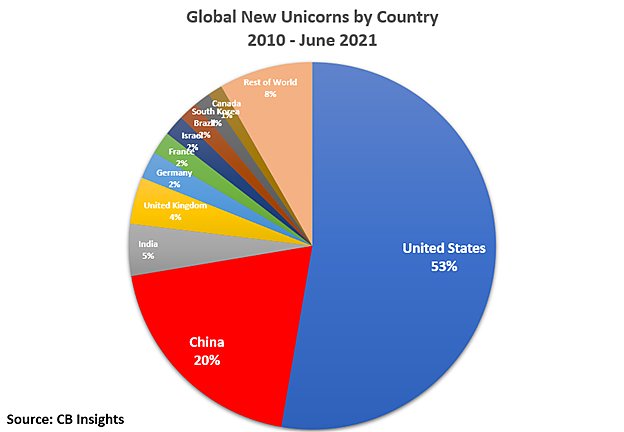

The U.S. start-up ecosystem is still quite strong (via Adam Thierer):

The Links

Young American adults aren’t working or studying

“The $670B College-Industrial Complex Is Under Threat From Online School”

Did customs misreporting cause the U.S.-China trade deficit to “decline”?

China’s Boeing/Airbus rival is reliant on U.S. and EU parts (and still not competitive)

Anne Kreuger on U.S. industrial policy

Some problems with Biden’s infrastructure plan (more)

Vox on NEPA and abnormally high U.S. infrastructure costs

How Buy American makes U.S. rail projects ridiculously expensive

Israel, the Delta variant, vaccines, and bad math

Significant correlation between a state’s vaccination and its economic performance

Biden should enlist Red Team members to encourage vaccines

How the USA’s Japan hysteria of the 1980s/1990s should inform China policy today

“There’s like a free market of the future of work”

Wealth inequality over the last 10 years

Norway paid Gabon to preserve its rainforest

Free Britney (no, seriously)

Wing shortage gives chicken thighs their much deserved moment