Dear Capitolisters,

As readers of this newsletter surely know by now, I’m a bit of an economic optimist (and that’s a bit of an understatement). If you gave me $100 and asked me to bet on the long-term direction of the U.S. economy using almost any national metric, I’d bet $90 on “upward” and then go invest the rest in VOO or ITOT (if you know you know). Even right now, I think the post-pandemic U.S. and global economies, while still in their perpetually confused state, will avoid the worst-case scenarios discussed in January. We might even avoid a recession in the U.S. altogether.

That said, I’ve been amazed, confused, and frustrated to watch various economists and pundits look upon Americans’ continued displeasure with the U.S. economic situation and act as if it’s all a media creation or just dumb/partisan square-staters projecting their political preferences upon the obviously great Biden economy. There are plenty of good, sane—though perhaps not economically sound—reasons for lots of Americans to dislike both the U.S. economy today and the president’s claims to the contrary.

The American Economy and Its (Many) Discontents

Plenty of economic indicators show that the U.S. economy is doing okay overall: GDP growth has been steadily positive and could be even stronger for the third quarter; the labor market is cooler, but still pretty warm; only one of the six monthly recession indicators used by the National Bureau of Economic Research is contracting (and barely so); and, of course, inflation—while still not back to pre-pandemic “normal”—has definitely cooled a lot since last year. All in all, there’s plenty for an economist to like.

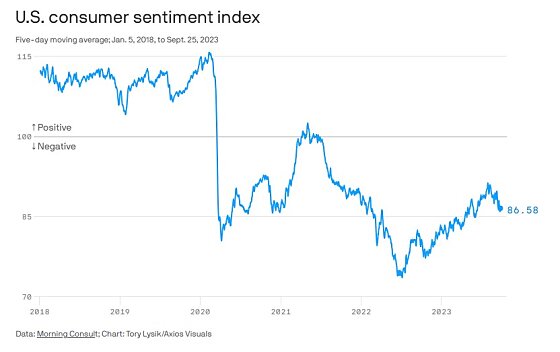

Non-economists, however, just aren’t buying it. As Axios reported last week, Americans’ views on the economy are trending back toward pandemic-era lows:

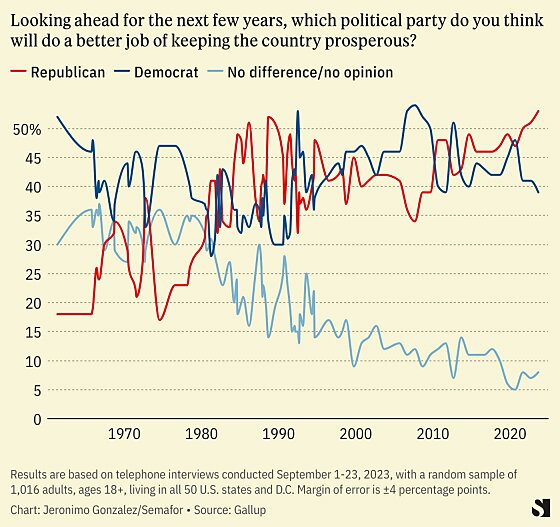

This sour national mood is unsurprisingly showing up in political polling too, with the GOP enjoying its biggest advantage on the economy since 1991. (Whether we like it or not, the party in the White House typically gets credit or blame for the perceived state of the economy.)

So, what’s going on here? Are Americans really suffering from mass, Fox News-induced delusions about the U.S. economy?

In short, no.

It’s (Sorta) the Economy, Stupid

Leaving aside for the moment that there may be bigger economic storm clouds on the horizon (see this recent Bloomberg dive for some reasons why), Americans’ distaste for the current economic situation is perfectly understandable—even if it’s not technically in line with the current national econ statistics.

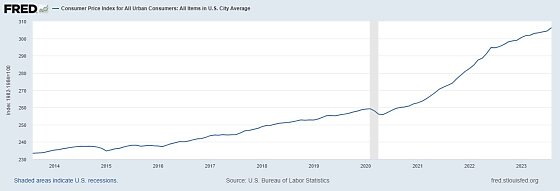

The obvious place to start is with prices—especially prices of the necessities that people buy all the time. It’s undoubtedly true and good that overall inflation (i.e., the rate of change in the price level overall) has cooled substantially over the last year, mainly thanks to supply chain improvements, lots of Federal Reserve tightening, and fiscal policy changes. However, today’s inflation trend is still well above the pre-pandemic trend and, more importantly, price levels are way, way above where they were just a few years ago. Indeed, economist Mark Zandi estimates that American households making the median income today pay $734 more each month to buy the same goods and services as they did two years ago. Even if he’s off by half, that’s still a lot.

Many economists, on the other hand, see this chart’s recent trends as a great sign that we’re returning to the kind of slow, steady inflation that is good for the economy and was the norm in past decades. A vocal handful, as noted, have even openly questioned why normies don’t get this and think the economy—and inflation—is still terrible. The answer is actually simple: Normal people don’t just want inflation to slow; they want prices to decline back to where they were before inflation took hold.

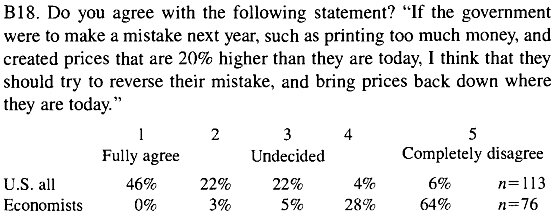

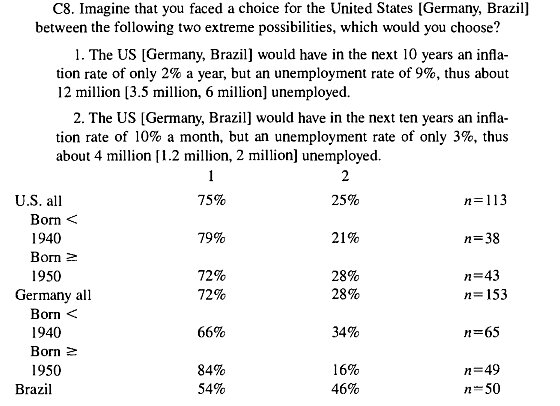

Economist Robert Shiller showed this well in his classic 1997 survey on inflation. When asked about inflation remarkably similar to what we just experienced, most Americans want prices to go back down, while most economists don’t.

The Washington Post’s Catherine Rampell recently found similar sentiments among today’s normies. They don’t just want moderating inflation; they want full-on deflation.

As Rampell and others have explained, there are good reasons for economists to reject this idea. For starters, the deflation many of us want is effectively impossible without a major recession, in part because U.S. companies have raised wages (to hire or retain inflation-hit employees) and can’t suddenly lower them now. Many economists also believe that sustained deflation would be quite bad for the U.S. economy. Growth would slow as rational consumers delayed purchases (to wait for bigger deals in the future); the high corporate debts taken out in the inflationary period would become harder to repay because revenues taken in during the deflationary period are lower; and so on.

But this doesn’t mean it’s not totally sane and rational for people to be highly annoyed that, say, monthly bills and budgets are consistently above the amounts to which they’ve become accustomed. And, unlike a raise (much of which will get eaten by taxes anyway), those bills just keep coming—every week or month.

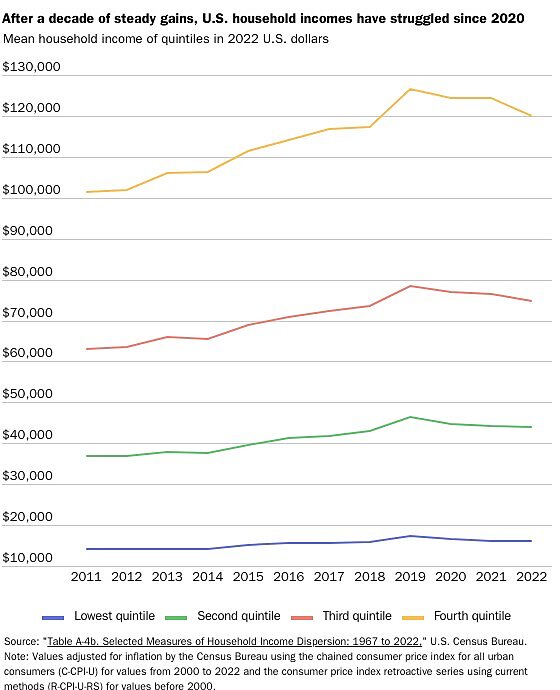

Admittedly, rising compensation can make up for higher prices today, but that too raises real concerns. For starters, various measures of middle class wages and compensation are up versus 2019, but they were down substantially last year, so it can be rational for people to worry that past real wage gains won’t continue in the future. And these gains can vary a lot by education, demographic factors (race, age, etc.), and geography, or even disappear entirely for some workers and especially for people on fixed incomes. Indeed, other measures of worker compensation, most notably the Census Bureau’s annual take on inflation-adjusted household incomes, shows substantial annual declines for every income group since the pandemic began. (Note: I removed the wealthiest quintile to make the chart below look a little better here, but the trend was basically the same.)

As we’ve discussed, these income figures aren’t perfect for various wonky reasons, but the trends are still notable and clear: Things were going pretty well before the pandemic, and now … not nearly as well.

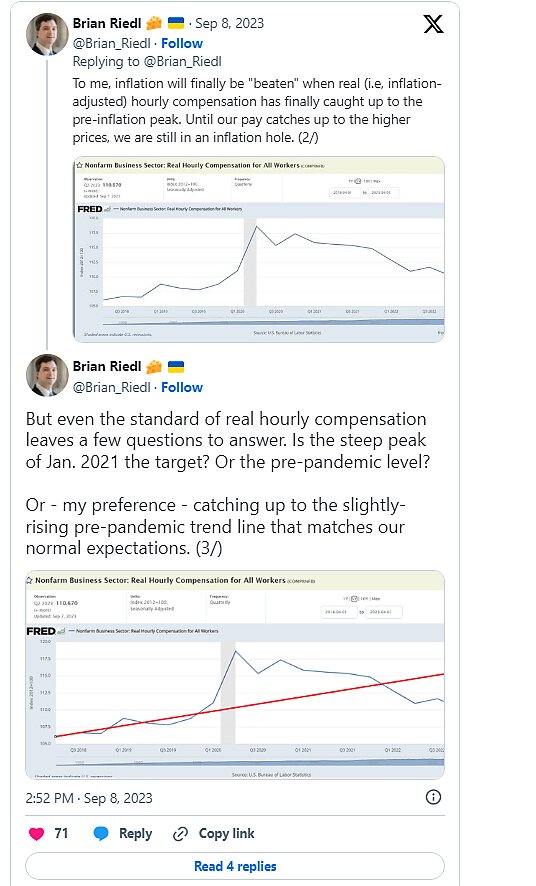

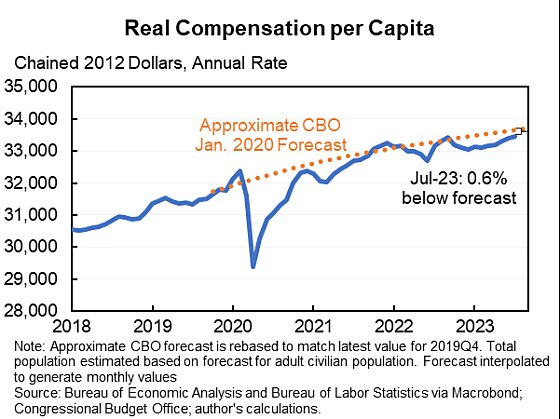

This contrast also gets to something the Manhattan Institute’s Brian Riedl recently noted: it’s rational for Americans to want more than just treading slightly above water in 2023 (assuming that’s what they are even doing). Yes, hourly compensation generally exceeds 2019 levels, and that’s good, but those gains are still well below the pre-pandemic trend:

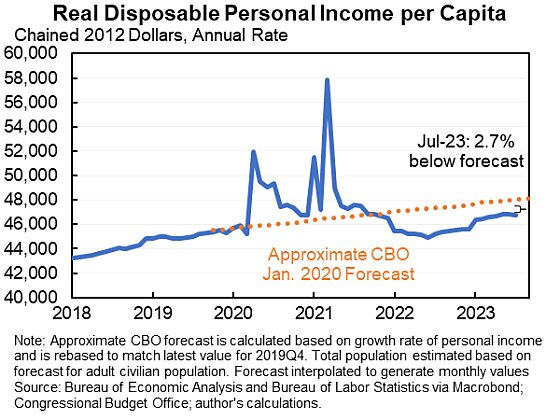

Harvard’s Jason Furman’s shows much the same for disposable income and per capita compensation:

If you, say, enjoyed a decade of 2 percent annual, inflation-adjusted income growth before the pandemic, it’d be quite natural to avoid cheering today about being just 2 percent above where you were in 2019.

Finally, that same Shiller survey shows that people generally believe inflation hurts everyone (including them), while unemployment, which would undoubtedly rise a lot during a deflationary recession, will hurt someone they might know, but not the respondents themselves:

That view is less rational than the other stuff, of course, but it is what it is (and worth knowing).

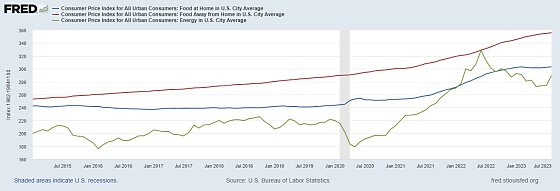

Another reason for understandable price-related concern is that many of the most highly visible prices are still historically elevated—especially for daily necessities. As the Wall Street Journal recently documented, “Prices for many items, though rising more slowly this year than last, remain well above their levels just before or at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and aren’t likely to return to where they were.” Most notable are food and energy, which everyone needs and regularly buys but which economists exclude from “core inflation” because of their volatility and disconnect from monetary policy (thus exacerbating the disconnect between what normies and economists think):

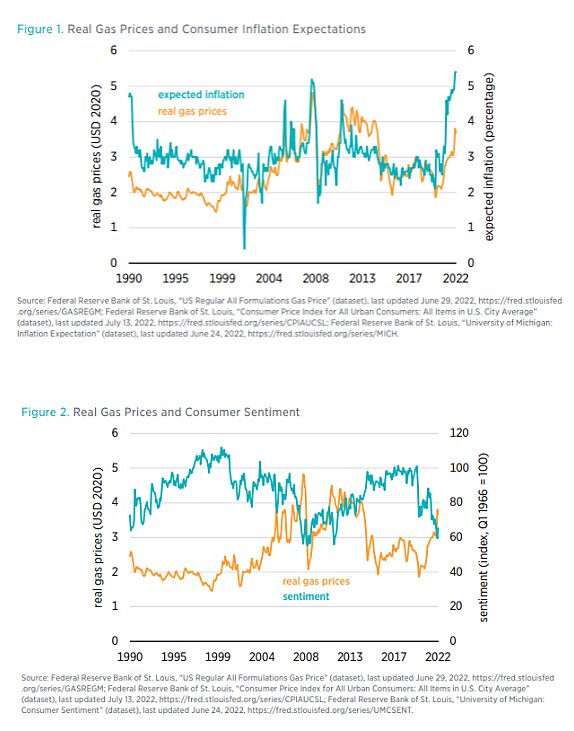

Yes, food and energy prices have moderated in recent months, but this is probably cold comfort to people still paying much more for the stuff they can’t do without—and facing that reality multiple times per week. And, as noted in a recent study from the Mercatus Center’s Carola Binder on gas prices in particular, consumers’ persistent attention to these prices can affect Americans’ views of the overall economy and future inflation. As shown below, in fact, gas prices are tightly correlated with both inflation expectations and consumer sentiment:

With gas prices getting higher once again, it’s inevitable—even if unfair—that Americans’ economic views will trend lower.

Binder shows that it’s both the visibility of gas price changes and their speed that make them so influential. This sentiment probably also applies to other products and to inflation generally. Generations of Americans (including this one) became accustomed to low inflation over a very long period. So, for example, we didn’t get too ticked to discover that the $1.50 Happy Meal from our foggy youth now costs two to three times that amount today. When prices suddenly jump a lot, however, the memories of “cheap stuff” aren’t distant—they’re “just the other day” —and that lucid comparison will inevitably rankle us more. (I recently experienced this sticker shock when buying my goal-scoring daughter some Burger King after her most recent soccer game. Yikes.) Finally, Binder notes that older Americans who lived through the Bad Old Days of oil price shocks get even more jittery than their younger peers. This, again, likely applies to inflation more broadly too, especially since those who remember the 1970s might now be on fixed incomes (and thus less able to cope with higher prices).

Then There Are Interest Rates

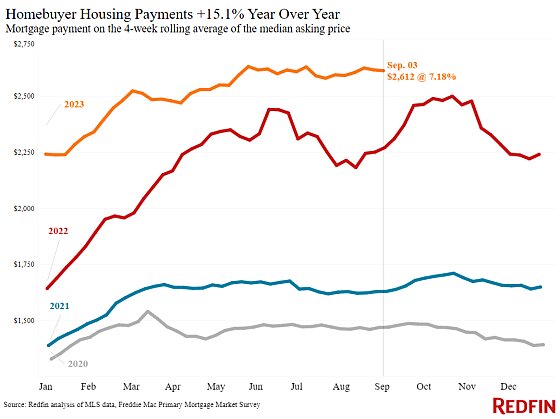

It’s not, however, just consumer prices that are taking an understandable bite out of Americans’ enthusiasm for the current U.S. economy. The other increasingly big issue is interest rates, which are good for savers and the many Americans who locked into low-rate debt, but are quite bad for everyone else—especially younger people who are looking to buy their first car or house and are more likely to have some variable-rate debt (because they haven’t built up savings or income yet). Housing in particular is just brutal right now, because mortgage rates are way up (and may be going even higher), but prices are still rising because supply remains limited. Some of that latter issue is, as we discussed in August, about supply-side restrictions on building new housing, but much of it is also because of interest rates: Americans who locked in absurdly cheap mortgages in 2020 or 2021 are moving now only if they have no other choice. Put it all together, and the housing market is—as Redfin just explained—pretty terrible, and Americans’ mortgage payments are way up:

With the median U.S. home-sale price up 4.5% year over year during the four weeks ending September 3 and mortgage rates remaining above 7%, the typical monthly mortgage payment is $2,612, just $18 shy of the all-time high set in May. High housing costs are dampening homebuying demand, with mortgage-purchase applications falling to a 28-year low.

Prices are rising due to a supply shortage: The total number of homes on the market is down 18% year over year, the biggest decline since February 2022. New listings are down 9% as many homeowners refuse to part with relatively low mortgage rates. But there are still more buyers than sellers in much of the country.

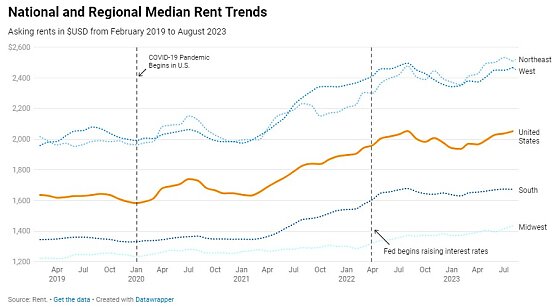

Rents, for what it’s worth, are also hovering around all-time highs so it’s not like renting is a great option either (though it certainly depends on the location and your situation).

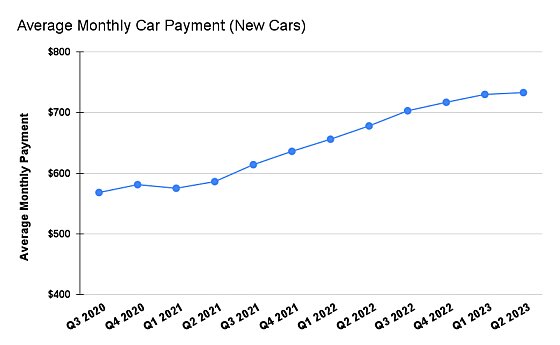

It’s a similar story for cars. Yes, there are a handful of truly affordable (cheap, even) cars out there still, but that number is dwindling: “In December 2017, automakers produced 36 models priced at $25,000 or less. Five years later, they built just 10.” And these higher car prices have combined with higher rates for auto loans to push average payments on new and used cars to new records:

Combine this with rising credit card debt, almost all of which is at (high) market rates, and we see that personal interest payments have increased rapidly in recent months to levels not seen since before the Great Recession:

Is this—or current price levels—an economic emergency or sign of impending doom? Probably not. But it’s quite easy to see why many Americans might not feel good about their economic prospects right now, especially as student loan payments kick back in and other “temporary” pandemic-era subsidies disappear—which they should have done a long time ago, by the way.

‘Bidenomics’ for the Few

Of course, much of this stuff—inflation, high prices, interest rates, etc.—isn’t the president’s or even U.S. policymakers’ fault. Reasonable minds can disagree about the extent to which policy (deficit spending, regulations, tariffs, etc.) affected the issues tarnishing Americans’ views of the economy, but a lot of it—monetary policy, supply chain problems, demographic changes, etc.—has nothing to do with the White House’s agenda.

Still, some of it surely is the result of Biden-era policy (especially spending and tariffs), and the administration’s strategy isn’t exactly helping matters.

Most obviously, it was the White House who chose to embrace the “Bidenomics” label and set out on a victory tour this summer, taking full credit for the U.S. economy’s upswing. It’s logical and expected that Americans’—and Republicans—would similarly blame Biden for the economy’s problems (real or perceived). You can’t pat yourself on the back for cheap gasoline one day and then pull a Shaggy now that oil’s back near $100/barrel. Turnabout is fair and inevitable play (especially when you frequently demonize oil and gas production too).

Furthermore, the president’s big Bidenomics push isn’t really addressing the direct economic concerns of most Americans—even ignoring the various left-wing surrogates who’ve lazily resorted to just telling worried Americans that they’re stupid or brainwashed. Instead, the most common and high-profile Bidenomics events and speeches relate not to kitchen table issues like gas prices but to grandiose manufacturing projects backed by U.S. industrial policy (the IRA, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the bipartisan infrastructure law). Yet, as Rampell noted in a separate column in September (and as I’ve noted ad nauseam here), Bidenomics’ apparent manufacturing “fixation” relates to “a sector that almost no Americans work in anymore, that doesn’t feel relevant to their daily lives and that isn’t actually doing so great right now.” Maybe those projects are good for national security or the environment (we shall see), and they surely produce some visible local jobs. But they’re just-as-surely not what most Americans— the vast majority of whom work in services and live in other places—care most about.

The president’s most intense and high-profile Bidenomics exercise—relating to the United Auto Workers strikes —is even more myopic. Reason’s Eric Boehm (with help from Gary Winslett) explains:

Far from being a broad-based signal of support for blue-collar Americans, Biden’s advocacy on behalf of the UAW this week will be performative shilling for a mere sliver of the country’s workers. In fact, it’s actually less than 1 percent, as Middlebury College political science professor Gary Winslett pointed out on Twitter last week. According to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, about 7.8 percent of American workers are employed in manufacturing jobs, and about 8 percent of manufacturing workers are members of a union. Put those figures together, and the result is that only about 0.62 percent (or roughly 842,000) of America’s 135 million workers fit into both categories.

“If the American labor force were visualized as 500 workers, only 3 of them fit this image,” Winslett helpfully explains.

That’s a useful way of illustrating one of the biggest disconnects between reality and our political rhetoric—which continues to equate the interests of unions with the interests of working-class Americans, even though unionization rates have been falling for decades.

As Boehm goes on to note, Biden’s picket-line move may be smart politics—people still like unions (though not enough to join one!) and he needs union votes in 2024—but the picket line in Michigan is not almost all Americans’ economic reality. And if the UAW strike lingers on and U.S. car prices start going way up again, those economic polls could head further south (like U.S. autoworker jobs—ha).

And it’d all be perfectly understandable.

Chart of the Week

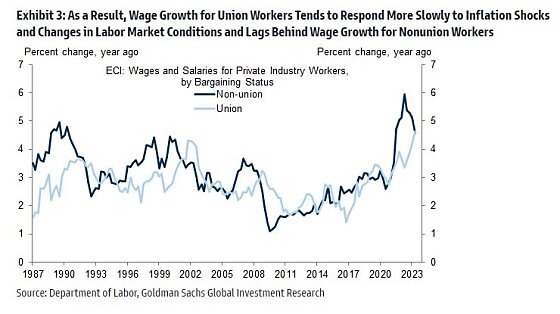

Goldman: Unions follow, don’t lead, wage gains (no link)