Part of the Jones Act’s stated purpose is to ensure the viability of the U.S. maritime and shipping industries. Clearly, the act is protectionist, as it prevents foreign-flagged ships from carrying cargo between U.S. ports. However, reduced competition in both shipbuilding and in transporting goods inevitably leads to higher prices. For example, Jones Act ships can cost three times as much to build as those built in low cost foreign shipyards. Critics of the act argue that a large fraction of these costs is passed on to the final consumers, who have to pay higher prices for the transported goods, or for goods using high-cost inputs transported by Jones Act vessels. Places like Hawaii and Puerto Rico are considered to be particularly affected due to their reliance on maritime transportation.

Proponents of the Jones Act argue that it helps the U.S. maritime industry and that it is vital to national security. While the national security argument has some merit, the high costs associated with the Jones Act have led consumers of transportation services to seek alternatives to maritime transportation within U.S. borders. As a result, many highways, for example, along the coasts, tend to be busier than they would otherwise be. In addition, the high costs have led to a steady long-term decline of the size of the U.S. commercial fleet.

Despite the importance of the Jones Act, there is little economics literature devoted to a rigorous evaluation of the costs and benefits that it generates for the U.S. economy. As the active debate on the act suggests, its consequences are, at least partly redistributive: protectionism creates an additional surplus, in the form of increased profits for industry participants, at the cost of reducing the surplus to other producers, consumers of transportation services, and final consumers. To properly evaluate these costs and benefits, we need to compare the total consumer and producer surplus in the presence of the Jones Act to the corresponding surpluses that would emerge if the act were to be repealed. Starting with the current status quo under the Jones Act, we would need to compare the current total surpluses to the corresponding ones absent the Jones Act, in which case competition resulting from the entry of foreign producers would bring prices to equal the world-price level. Most foreign-flag vessels operate in competitive, largely unregulated markets, and are often subject to low compliance costs. As a result, and since foreign and domestic vessels are largely considered to be near perfect substitutes in transportation, foreign competition would likely result in significant reductions in freight rates, should the Jones Act be repealed.

Of course, the Jones Act has far-reaching implications for the entire U.S. transportation sector and beyond that are impossible to capture in their entirety. As an example, the U.S. trucking and rail industries, as well as the ports, would be affected in complex ways, if the Jones Act were to be repealed. Perhaps most importantly for our focus, the domestic maritime industry would, at least in the beginning, most likely be largely uncompetitive given its higher cost structure, leading to a decline in the size of the domestic fleet, as only the most efficient and low-cost domestic firms would be able to compete. For a complete cost-benefit analysis, such losses in domestic producer surplus need to be aggregated and compared with the total increase in consumer surplus. The resulting net effect will determine the desirability of a potential policy change.

There are very few studies by economists considering the implications of repealing the Jones Act. Stopfordi provides a comprehensive treatment of several topics related to maritime economics. Smithii documents the decline in U.S. merchant marine employment since the Jones Act was implemented. Papavizas and Gardneriii discuss changes to the coastal shipping market that might occur should the Jones Act be repealed. Lewisiv computes a low bound for the losses associated with the Jones Act.

Importantly, even if rigorous analysis convincingly concludes that repealing the Jones Act would lead to overall welfare (surplus) gains, this would likely be far from sufficient to make progress towards repealing the act. Since any potential changes to the act will create big losers, as well as (even bigger) winners, a discussion is needed on how the winners might at least partially “compensate” the losers, at least in the short run. As we have been painfully witnessing over several decades, absent such compensation, it will be difficult to create the consensus that is necessary to implement changes. Yet, critics of the Jones Act seldom discuss the size and the form of the “carrot” that will be necessary to induce cooperation from the Jones Act industry.

Welfare Analysis: Consumer and Producer Surplus

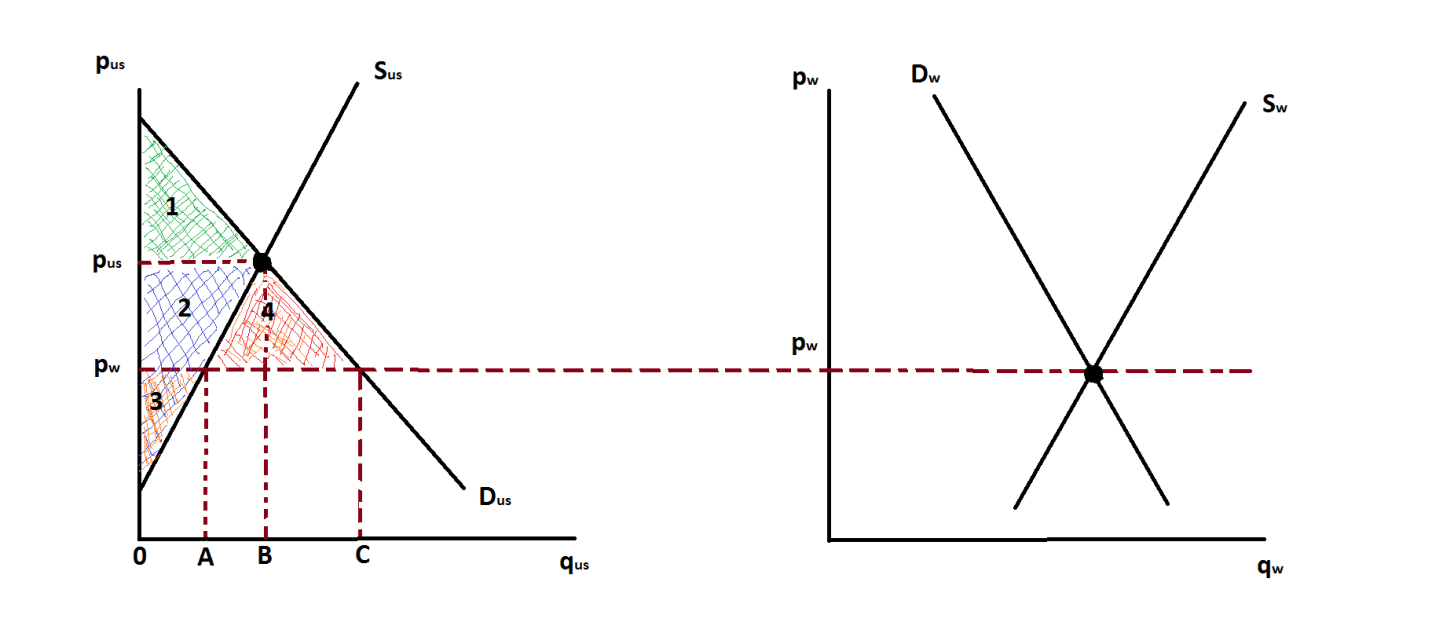

The qualitative aspects of the welfare analysis are summarized in Figure 1 below. To fix ideas, one can consider a single Jones Act market, for example, product tankers. First, let us consider economic equilibrium in the status quo; i.e., in the presence of the Jones Act. The graph on the right represents the world equilibrium product tanker freight-rate, pw, as determined by world supply and demand. This is lower than pus, the resulting freight rate in the U.S. under the Jones Act (left graph). The equilibrium quantity of maritime transport services by Jones Act vessels is represented by the horizontal distance 0B. The total welfare created in the U.S. is then given by the sum of the consumer surplus (area 1) plus the producer surplus (area 2+3).

What if the Jones Act was to be repealed? Once permitted, foreign vessels would find it attractive to enter the U.S. market and supply their capacity at the initially high rate, pus > pw. This would increase the supply of vessels in the U.S., thus, bidding the price down to the world price, pw. The total quantity of maritime transportation services in the U.S. extends all the way to 0C. However, notice that only interval 0A is produced by U.S.-flagged vessels. These are the lowest-cost domestic vessels, which would compete with foreign providers. The remaining supply, as given by distance AC, represents supply by foreign vessels.

The figure tells a robust qualitative story. While repealing the Jones Act would increase the total quantity transported across U.S. ports, the quantity transported by U.S.-flagged vessels is likely to decrease. The overall result is that U.S. consumer surplus would increase to area 1+2+4 (from area 1 previously), while U.S. producer surplus would shrink to area 3 (from area 2+3 previously). Thus, repealing the Jones Act would redistribute some existing surplus (area 2) from U.S. producers to U.S. consumers. However, this is not all. Repealing the Jones Act would also add to overall efficiency, by eliminating a deadweight loss (area 4). Determining the magnitude of these efficiency gains is a quantitative question.

Figure 1. Economic Surplus

Conclusion

Repealing the Jones Act will inevitably lead to an economic surplus redistribution. Domestic consumers of transportation services as well as final consumers of goods currently transported by Jones Act vessels would gain (areas 2+4), while the profits and size of the current Jones Act fleet would decline (area 2). Since the presence of the act implies non-negligible overall deadweight welfare loses (area 4), it is almost certain that there would be overall welfare gains, should the Jones Act be repealed. Two issues arise. First, the gains have to be weighed against the potential implications to U.S. national security (which are rather hard to quantify directly). In other words, we can compute a lower bound on how large the national security benefits of the act need to be in order to justify the welfare losses created by the act. Second, to go from theory to practice, in order to induce legislative change, the winners will need to in some way compensate the losers for the corresponding loss in surplus. The model presented here asserts that this should be possible, as market liberalization would be associated with an overall welfare gain. However, this will require the establishment of an active dialogue between critics of the act and representatives from the Jones Act industry.

Notes:

i Martin Stopford, Maritime Economics (2nd. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis e‑Library, 2003).

ii Richard A. Smith, “The Jones Act: An Economic and Political Evaluation,” Boston: MIT Dept. of Ocean Engineering, 2004.

iii Constantine G. Papavizas and Bryant E. Gardner, “Is the Jones Act Redundant?,” U.S.F. Maritime Law Journal, 21, no.1 (2009).

iv Justin Lewis, “Veiled Waters: Examining the Jones Act’s Consumer Welfare Effect,” Issues in Political Economy, 22, (2013).

Additional References

J. F. Francois, H. M Arce, K. A. Reinert & J. E. Flynn, “Commercial Policy and the Domestic Carrying Trade,” The Canadian Journal of Economics, 29(1), 1996.

The opinions expressed here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Cato Institute. This essay was prepared as part of a special Cato online forum on The Jones Act: Charting a New Course after a Century of Failure.