At the “heart of MMT,” writes Kelton (2020), is the “distinction between currency users and the currency issuer” (original italics, p. 18). A currency issuer is a country that has monetary sovereignty. Four conditions, she contends, are needed to attain monetary sovereignty: (1) a country must issue its own currency (p. 19); (2) it must borrow in that currency (p. 145); (3) it must let its currency float against other currencies (p. 145); and (4) the currency in question must be inconvertible—that is, it is “also important that [countries] don’t promise to convert their currency into something of which they could run out (e.g., gold or some other country’s currency)” (pp. 18–19). Countries like the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, and “many more,” Kelton asserts, are currency issuers. These countries “never [have] to worry about running out of money.” The United States, for example, “can always pay the bills, even the big ones” (p. 19) because it can always print enough dollars to pay those bills.2 Kelton writes: “Congress has the power of the purse. If it really wants to accomplish something, the money can always be made available … spending should never be constrained by arbitrary budget targets or a blind allegiance to so-called sound finance” (p. 4). Fiscal deficits, she argues, are not a problem so long as the deficits do not lead to inflation (more about that shortly). “This book,” Kelton audaciously asserts, “aims to drive the number of people who believe the deficit is a problem closer to zero” (p. 8).

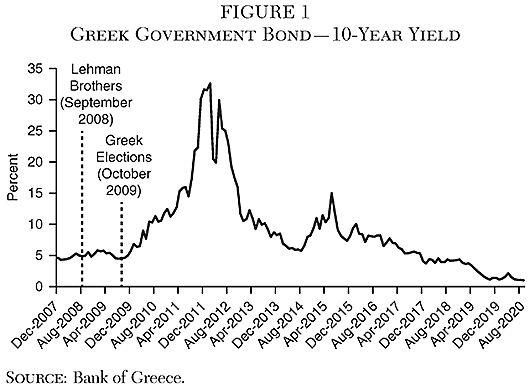

The situation for currency users is very different. The countries that fall into this category have either (1) fixed their exchange rates, “like Argentina did until 2001,” or (2) “taken on debt denominated in a foreign currency, like Venezuela has done,” or (3) abandoned their national currency, as “Italy, Greece and other eurozone countries,” have done (p. 19). Those countries do not have access to the printing press to backstop their debts. Thus, we are told: “The US can’t end up like Greece, which gave up its monetary sovereignty when it stopped issuing the drachma in order to use the euro” (p. 19).

As mentioned, Kelton (pp. 60–63) acknowledges that MMT is guided by the idea of functional finance, developed by Lerner. Let’s take a look at what Lerner had to say about functional finance. In his 1944 book, The Economics of Control, Lerner argued that the government should not hesitate to incur fiscal deficits required to achieve full employment. If the attainment of this objective entails persistent fiscal deficits (or surpluses), so be it. The size of the national debt, Lerner argued, is not important: “The [size of the] debt is not a burden on posterity because if posterity pays the debt it will be paying the same posterity that will be alive at the time when the payment is made. The national debt is not a burden on the nation because every cent in interest or repayment that is collected from the citizens as taxpayers to meet the debt service is received by the citizens as government bondholders” (Lerner 1944: 303).3 Likewise, argued Lerner, “the interest on the debt is not a burden on the nation” because those payments “are merely transferred to the recipient from taxpayer or from new lenders, and if it should be difficult or undesirable to raise taxes the interest payment can be met, without imposing any burden on the nation as a whole, by borrowing the money or printing it” (Lerner 1944: 303).

Kelton believes that Lerner “turned conventional wisdom on its head,” since Lerner showed that the size of a nation’s debt and its fiscal position are unimportant. Kelton states: “Instead of trying to force the economy to generate enough taxes to match federal spending, Lerner urged policy makers to think in reverse. Taxes and spending should be manipulated to bring the overall economy into balance” (p. 61). Such a policy might require “sustained fiscal deficits over many years or even decades” (p. 61). So long as inflation remains under control, “Lerner saw this as a perfectly responsible way to manage the government budget” (p. 61). Kelton’s depiction of Lerner’s argument that fiscal deficits and the size of a nation’s debt do not matter is accurate so long as a very important qualification made by Lerner is taken into account. In particular, Lerner made it clear that a necessary condition had to be in place for a nation’s fiscal position, including its debt level, not to matter. This condition, which I discuss below, is not taken into account by Kelton.

After describing Lerner’s concept of functional finance, Kelton expresses the following view: “Lerner’s insights are important to MMT, but they don’t go far enough.… We think Lerner’s prescriptions will still leave too many people without jobs” (p. 63). Lerner, argues Kelton, thought that attaining what he called full employment would be accompanied by a level of involuntary unemployment, leaving some people out of work. To ensure that everyone has a job, “MMT recommends a federal job guarantee, which creates a nondiscretionary automatic stabilizer that promotes both full employment and price stability” (p. 63).

Here is the way MMT’s economic program would work. The Federal Reserve would become subservient to the U.S. Treasury. To ensure that “funding … can always be made available” (pp. 234–35) for whatever purpose is deemed worthwhile, “the Federal Reserve carries out an authorized payment on behalf of the Treasury” (p. 235). Specifically, the Fed would print whatever money was needed to finance the government’s spending intentions: “[W]e must recognize that the US government can supply all the dollars our private sector needs to reach full employment, and it can supply all the dollars the rest of the world needs to build up their reserves and protect their trade flows” (original italics, p. 151). What spending would be worthwhile? In addition to the federal job guarantee, the ability to print currency would provide the fiscal space to fund Medicare for all; free college; middle-class tax cuts; a full Green New Deal; free child care; the cancelation of student debt; affordable housing for everyone; a national high-speed rail; a Civilian Conservation Corps, the responsibilities of which would include fire prevention, flood control, and sustainable agriculture; and expanded Social Security. MMT’s program would reduce racial inequalities, decrease poverty, build stronger communities, and more (pp. 229–63).

Under the federal job-guarantee program, if “the economy were to crash the way it did in 2008, the job guarantee would catch hundreds of thousands of people instead of allowing them to fall into unemployment” (p. 67). Moreover, the government would steer spending to preferred sectors of the economy. Thus, Kelton argues that: “With decent jobs guaranteed for all, workers can engage in a public-led industrial policy aimed at producing sustainable infrastructure and a wider array of public services” (italics supplied, p. 152). The program would establish a wage floor of “say $15 per hour” (p. 68). That floor, in and of itself, would help “to stabilize inflation by anchoring a key price [i.e., the wage rate] in the economy” (p. 67). Yet, despite the foregoing menu of spending intentions, Kelton tells the reader that MMT “is not a plot to grow the size of government” (p. 235).

Apart from the minimum wage’s anchoring role under the federal job program, how would Kelton keep inflation in check? She is very vague: “MMT would make us safer [against inflation] because it recognizes that the best defense against inflation is a good offense” (original italics, p. 72). What is a good offense against inflation? She continues: “We want agencies like the CBO helping to evaluate new legislation for potential inflation risk before Congress commits to funding new programs so that the risks can be mitigated preemptively.” In this connection, “If the CBO and other independent analysts concluded it [higher spending] would risk pushing inflation above some desired inflation rate, then lawmakers could begin to assemble a menu of options to identify the most effective ways to mitigate that risk” (original italics, p. 72). What are these options? Congress would “work backward” to identify areas where spending could be cut, thus ensuring “that there is always a check on any new spending. The best way to fight inflation is before it happens” (original italics, pp. 72–73). Essentially, Kelton maintains that there is always spare capacity in the economy such that the aggregate supply curve is flat. Consequently, a large, sustained fiscal stimulus, financed by money creation, would neither crowd out private expenditure nor ignite inflation.

With fiscal policy bearing the heavy work in economic stabilization, Kelton asks: “Can fiscal policy really take over the economic steering wheel? What’s left for monetary policy?” (p. 242). With the Federal Reserve having become an arm of the Treasury, monetary policy—open-market operations, changes in the discount rate, and changes in reserve requirements—merit essentially no role in Kelton’s scheme: “MMT considers fiscal policy a more potent stabilizer [than monetary policy]” (original italics, p. 243).

Two points about the financing of the fiscal deficits under MMT are important. First, as indicated in the foregoing synopsis of Kelton’s book, money creation would be the primary means of financing increases in government spending. Kelton argues that money and government bonds are essentially identical assets in private-sector portfolios. Why, then, does the government borrow? Why not just pay for government spending by running the printing press? Kelton states: “[The government] chooses to offer people a different kind of government money, one that pays a bit of interest. In other words, US Treasuries are just interest-bearing dollars” (original italics, p. 36). It follows that the government can make “the national debt disappear” by letting the Federal Reserve purchase all the outstanding government debt (p. 99).4 Thus, “the purpose of auctioning US Treasuries—that is, borrowing—isn’t to raise dollars for Uncle Sam” (p. 36).5

Second, as is the case with sovereign borrowing, Kelton believes that taxation should not normally be used to finance government spending. Nevertheless, she maintains that taxes serve several key functions within an economic system: (1) “taxes enable governments to provision themselves without the use of explicit force”—without that tax obligation, people would not have a reason to demand the government’s fiat currency (p. 32); (2) should the need arise, taxation provides a means to combat inflation (p. 33); (3) “taxes are a powerful way to alter the distribution of wealth and income” (p. 33); and (4) taxes are a way “to encourage or discourage certain behaviors” (p. 34).

The MMT framework, including Kelton’s rendition of that framework, has been subjected to considerable, tough criticism from leading economists. Kelton’s rendition, for example, has been criticized for (1) its neglect of the 1970s, a period during which expansionary policies led to increases in both inflation and unemployment (Cochrane 2020); (2) the likelihood that it would induce unexpected inflation, reducing the purchasing power of those caught holding “old money” as “new money” is printed (Andolfatto 2020, Dowd 2020); (3) its strong proclivity to increase the size of the government in the economy, thereby diverting resources from productive firms to the quixotic public sector (Coats 2019, Tenreiro 2020); (4) its neglect of the fact that, in the absence of monetary accommodation, fiscal expansion can be a weak policy instrument (Greenwood and Hanke 2019); and (5) its neglect of the literatures on central-bank independence, the term structure of interest rates, and the effects of portfolio-balance decisions by investors on the way that policies interact with key economic variables (Edwards 2019).6 Krugman (2019) likened MMT to Calvinball, a game under which its adherents keep changing their arguments in response to criticisms; Rogoff (2019) called MMT “nonsense”; and Summers (2019) wrote that it is “a recipe for disaster.” Yet, in the present low-inflation environment, MMT continues to thrive in certain political circles and to be the focus of debate among academics while Kelton has become the leading spokesperson for the movement. After all, if inflation has remained below 2 percent in most major economies despite the highly expansionary monetary and fiscal policies of the past decade, why not take advantage of the benefits that MMT promises to deliver? Let me, therefore, assess MMT through the lens of Kelton’s “poster child” currency user.