Landes and Posner (1978) are the first to reference adoption agencies’ misaligned incentives, though only briefly. Gronbjerg, Chen, and Stagner (1995) and Zullo (2002, 2008a, 2008b) discuss private agencies’ use of leverage to win contracts and the prioritization of earnings over permanency outcomes. This article provides an updated evaluation of the role of incentives, and, drawing on references to rent-seeking behavior and public choice theory, discusses how the interplay between contracted agencies and corresponding government officials’ incentives hinders adoption out of foster care. First, I briefly characterize the market setting. Next, I analyze each party’s incentives, and, finally, I conclude with a discussion of limitations and policy implications.

How Misaligned Incentives Hinder Foster Care Adoption

Adoption, particularly adoption out of foster care, has not been well studied within the field of economics.

Adoption, particularly adoption out of foster care, has not been well studied within the field of economics. Researchers may avoid this topic because the adoption market greatly deviates from a typical market, and the system and data collection are highly fragmented, with relatively little federal coordination. Rubin et al. (2007) and Thornberry et al. (1999) show that instability in foster care placements produces negative welfare outcomes, and Hansen (2006), Barth et al. (2006), and Zill (2011) demonstrate that adoption out of foster care is socially and financially beneficial. Yet, children waiting to be adopted out of foster care are in excess supply, which has been exacerbated in recent years. I hypothesize that this is, in part, due to misaligned incentives of government officials and the contracted foster care agencies. I show that earnings are prioritized over ensuring permanent child placement, which hinders the potential for adoption, and government oversight fails to correct such iniquities because of career interests.

Characterizing the Market

While adoption is not frequently characterized in the context of a market, in its most basic form, adoption constitutes a transaction, with the “good”—the child—being transferred from the “supplier”—the foster care agency—to the “demander”—the parents. Government is a strong intermediary to help ensure the protection of child welfare (Moriguchi 2012).

The Supply Side

Children are placed in the foster care system either voluntarily, when parents who are unable to care for their child surrender their parental rights, or involuntarily, by court order in the case of abuse or neglect. For this reason, the children in foster care come disproportionately from troubled families. Although the total number of people under the age of 19 has not changed significantly in the last five years, the number of children in the foster care system has increased (Miller 2020). Neglect is the most common reason for the child’s removal (62 percent), but the opioid epidemic has become an increasingly important factor. Drug abuse accounts for 36 percent of the removals (USCB 2019a), though it is higher in some states, including Ohio, where it is estimated to be 50 percent (Reynolds 2017). If a child remains in foster care for 15 of the most recent 22 months, or if the state deems the parents unfit for guardianship (Children’s Bureau 2017), then the agency no longer aims to reunify the child with previous guardians; instead, parental rights are permanently terminated and the child becomes classified as “waiting to be adopted” (Bernal et al. 2007). The children will wait, on average, four years for adoption (USCB 2019a).

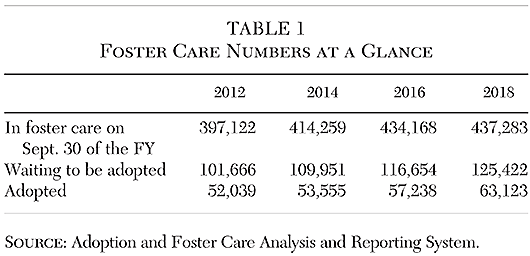

Currently, over 125,000 children in foster care await adoption (USCB 2019a). This “excess supply” has increased 25 percent between 2012 and 2018 (see Table 1), and for the past decade only about 50 percent of the number of children waiting for adoption actually do get adopted each year (USCB 2019b). Legislation has tried to promote reinstatement of birth parents’ rights as a way to address this glut, but a steady increase in legal orphans aging out of the system has persisted (Taylor Adams 2014).

The Demand Side

Parents who adopt out of foster care are frequently characterized as having “a big heart and limited resources” (Bernal et al. 2007). Among these parents, 86 percent were found to be motivated by altruism (i.e., to provide a permanent home for a child) and 39 percent by infertility (multiple answers allowed in the survey). Parents often select foster care over other adoption venues because it is less expensive; concordantly, foster care adoptive parents typically come from lower income backgrounds (Bernal et al. 2007; Bethmann and Kvasnicka 2012).

Government Intermediary

Each state runs its own foster care system independently, though many rely significantly on federal funding through block grants, particularly Title IV‑E of the Social Security Act (Taylor Adams 2014). Additionally, state governments have increasingly turned to private, often nonprofit organizations to be able to provide the full array of services needed, and thus the state-governmental role is primarily to set policy and provide oversight of private agencies (Krauskopf and Chen 2013). The contracts with private agencies vary widely, though they frequently stipulate some sort of fixed amount of reimbursement per day or month per child in care (USDHHS 2008). Most states give priority to relatives and current foster parents who are looking to adopt (Ledesma n.d.), because states increasingly view foster care as a steppingstone to adoption (Adoption Exchange Association n.d.).

Value of Adoption Out of Foster Care

It is well documented that adoption is an extremely valuable outcome for children in foster care. Placement instability among foster care homes has been shown to have a significant negative effect on a child’s well-being and future success (Rubin et al. 2007; Thornberry et al. 1999). Further, there is mounting evidence that quality parenting is extremely important for success at each stage of life (Reeves and Howard 2013; Kalil 2014), and that parenting need not be provided by a biological parent to achieve the same outcomes (Lamb 2012). Finally, Hansen (2006), Barth et al. (2006), and Zill (2011) have shown that adoption from foster care produces better future welfare and financial outcomes for both the child and society; compared to children who remain in foster care, children who are adopted out achieve better outcomes with regard to education, employment, criminal and disciplinary records, and social skills, among other categories. Adoption provides the government a net savings of $143,000 per child, and each dollar spent on the adoption yields $2.45 to $3.26 in benefits to society (Hansen 2006).

Evaluating Incentives

Given that the choice to adopt a foster child ultimately reduces the government’s fiscal burden and improves child and community outcomes, Hansen (2006) regards foster care adoption as a “positive externality.” Accordingly, it seems logical that parties involved in the market should promote this transaction. It is in the child’s best interest to be placed in a “foster-to-adopt” home as early as possible during their time in the system (Ledesma n.d.). Further, given that foster care parents themselves comprise 78 percent of nonrelative foster care child adoptions (USCB 2019a), placing a child in a safe and caring foster care family is of the utmost importance to promote ultimate adoption. However, it is clear that the current system does not optimally support adoption, as only half the number of children awaiting adoption are actually adopted (USCB 2019b) and children are increasingly aging out of the system (Taylor Adams 2014).

Contracted Agencies: Earnings Focused

Many agencies’ incentives conflict with child welfare and placement permanency goals. Zullo (2008a) suggests that privately contracted foster care agencies make decisions based on financial interests rather than child welfare. These agencies, whether for-profit or nonprofit, are typically paid per child in their care (USDHHS 2008). Therefore, each foster parent represents potential revenue (Zullo 2002) and many agencies provide bonuses to incentivize their workers to bring in more parents (CFUSS 2017). This means there is little incentive to reject inappropriate foster families, investigate concerns, or do anything that might cause the child to leave their program (Zullo 2002; Blackstone and Hakim 2003). In fact, on the contrary, Hatcher (2019) cites contract documents between the state and private foster care agencies that illustrate leadership officials sorting children not based on their needs but rather on how much revenue they can generate. As Zullo states, “What happens is the lives of these children become commodities” (Joseph 2015). As a result, private providers do not spend adequate time and resources on efforts to achieve permanent placement for children (Zullo 2008b).

In 2014, the Mentor Network was a leading provider of human and foster care services, operating in 36 states (CFUSS 2017). In 2015, BuzzFeed News and Mother Jones released a series of reports that suggested that Mentor placed children with neglectful and physically/sexually abusive foster care families as a way to boost profits. Former Mentor staffers stated, “The success of the program is defined by how many heads are in bed at midnight” and, “The bottom line is a dollar, not a child’s well-being” (Joseph 2015). Another former employee admitted, “I became a machine that cared about profits. I didn’t care about kids” (Roston and Singer-Vine 2015). Mentor, like half of surveyed agencies, receives almost 100 percent of its revenue from the government (CFUSS 2017: 7), yet it maintains profit margins in some states (Alabama, Ohio) as high as 31 percent and 44 percent (Roston and Singer-Vine 2015). Mentor’s profit-oriented practice is not an isolated incident; in fact, a Florida agency publicly reports its techniques to “score” foster children to maximize revenue. And in a Maryland assessment report, MAXIMUS, Inc., which has operated in 25 states, refers to foster children as a “revenue generating mechanism” (Hatcher 2019).

Nevertheless, Mentor’s scathing media coverage prompted the Senate Finance Committee to investigate privatization within foster care, using Mentor as a case study for the broader industry. It found that Mentor falsely reported that its death rate of children in its foster care system was in line with the national rate, when, in fact, it was 42 percent higher (CFUSS 2017: 24). The U.S. Senate Finance Committee found this report to be “inaccurate and misleading” (CFUSS 2017: 23) and found other reports to be ripe with inconsistencies, missing or inaccurate information, and “diagnostically implausible conditions” (CFUSS 2017: 22). Further, private for-profit agencies “too often failed to provide even the most basic protections” or to recognize and prevent dangerous conditions ex ante and ex post (CFUSS 2017: 2). With regard to both nonprofit and for-profit foster care agencies, the Committee ultimately concluded that “profits are prioritized over children’s well-being” (CFUSS 2017: 1).

Nonprofits

Critics may suggest that these aforementioned issues largely arise with for-profit businesses like Mentor and Sequel, and instead the government should only contract with nonprofits. A nonprofit business model theoretically could mitigate the profits-before-welfare mindset exhibited by for-profit businesses. However, given the recent indiscretions of some nonprofit foster care agencies, it is not clear that these businesses actually better utilize funds to promote welfare than do the for-profits. For example, Oregon previously contracted with nonprofit Give Us This Day to support foster care services. Between 2009 and 2015, the organization founder, Mary Holden Ayla, stole approximately $1 million of the federal funds the organization received. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation report, funds chronically ran short from this organization; employees would race to the bank on payday only to have their paychecks still bounce, and when faced with a lack of food in the homes the organization supported, Ayla simply told employees to utilize the food offered at food banks. Ayla did not even have her own bank account, but rather used the Give Us This Day account to pay for her personal expenses, including payments to luxury retailers, spas, her home mortgage, or vacation travels. All of these indiscretions occurred without any state oversight (Federal Bureau of Investigation 2019).

In a similar way, numerous other nonprofits have misappropriated funds. For example, Children’s Trust Fund, a nonprofit contracted by Los Angeles, requested government funds for children it did not even have in its care, and it funneled financial and nonmonetary donations to a personal account rather than to the DCFS as instructed (County of Los Angeles: Department of Auditor-Controller 2017). Child Link, a nonprofit contracted by Chicago, misused government funds for charges such as staff meals, traffic tickets, membership to a private social club, a $1,000 outing to a White Sox game, and a $6,000 Christmas party. These charges were made despite explicit rules dictating that state dollars could not be used on these types of expenses. Child Link was investigated at the urging of the state inspector general, and it marks the first time in six years that the Chicago DCFS actually conducted an extensive audit of one of its private partners (Gutoswki 2019).

Finally, in several states that do not allow or do not prefer to contract with for-profit agencies, a nonprofit agency may win the public contract and then subcontract out the services to for-profit agencies. This practice occurred in Illinois, which allowed Mentor (a for-profit agency) to effectively run state foster care services through a non-profit front called Alliance Human Services, Inc. In this instance, the state inspector general investigation found that rather than working for the best interests of the children and families, the agency staff “cultivated a culture of incompetence and lack of forthrightness,” and ultimately that “the absence of good faith demonstrated by the private agency undermined any faith the department or the public would be able to place in the organization” (Kane 2015: 124). Despite these findings, among others, as well as a strong recommendation for the Illinois DCFS to terminate contracts with this agency, the DCFS still indicated a preference to work with this provider moving forward (Roston 2015).

Government Inaction

Bureaucratic leadership is complicit in allowing these behaviors to occur, which, in part, may serve to encourage these agencies’ indiscretions further. These officials may fail to provide adequate oversight and discipline out of interest in attaining acclaim, money, or career success. As a result, children can be placed with unsuitable families, which prevents the opportunity for them to form a good relationship with their foster parents that could ultimately lead to adoption. This line of reasoning is concordant with public choice theory, which recognizes that government officials are driven by self-interest, and thus they work to maximize their own private interests rather than public interest (Dudley and Brito 2012).

There is widespread evidence that state oversight agencies are aware of neglectful or failing contracted agencies, but government leadership takes little action to end the contract, impose consequences, or improve the situation. For example, in a 2018 New York Department of Investigation report, auditors found that 21 out of 22 contracted foster care providers fell short on the federal maltreatment guidelines, and 19 out of 22 fell short by more than double; the lowest three providers scored 2, 19, and 10 out of a possible 100 for maltreatment, and 47, 50, and 55 (out of 100) for safety. The Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) recognized that these were “very bad scores,” but did not regard any scores as “failing,” and typically took no action to address performance issues (Peters 2018: 8). Actually, the ACS renewed contracts with all foster care providers without instituting any additional performance or safety standards (Peters 2018).

In Oregon, a 2018 audit found that the Department of Human Services (DHS) compliance staff noted concerns and recommended not to renew the license of the contracted agency Give Us This Day in 2005, 2009, and 2014. Instead, DHS leadership continued to extend the contract until 2015, when the Department of Justice forced the provider to cease operations. The auditors noted that Oregon DHS and Child Welfare suffer from “chronic and systemic management shortcomings that have a detrimental effect on the agency’s ability to protect child safety,” with managers completely unwilling to take responsibility for shortcomings, even within the program they directly oversee (Richardson and Memmott 2018).

In Oklahoma, the reviewers found that while the Oklahoma DHS itself had admitted serious accuracy issues with their reporting, staff had only taken “the most limited steps” to address them (Miller 2011: 2). There was a “lack of leadership, accountability, and there [was] no clear vision of the agency’s priorities” (ibid.). While in some ways this lack of oversight may be confounded or exacerbated by a lack of resources, in many cases, as in New York (Stein 2016) and Texas (United States District Court: Southern District of Texas 2015), investigative superiors have explicitly stated that failed oversight was not due to budget issues.

Revolving Door

This inaction reflects weak prioritization of child welfare. In fact, when the Senate Finance Committee requested information from all 50 states for their 2017 investigation, 17 states never responded to the request; the lead senator on the committee reacted by saying, “It’s kind of like some of these managers in states just consider protecting the children an afterthought, not a priority” (Grim and Chavez 2017). Instead, leadership’s priority may be personal career interests, as evidenced by the history of a “revolving door” between government and the private sector in this industry, which has been documented in other areas (Tabakovic and Wollmann 2018; Blanes-i-Vidal, Draca, and Fons-Rosen 2012; Cohen 1986). In order to encourage a future job possibility at a private agency, it is in the best interest of government leaders to award contracts and minimize discipline of private foster care agencies.

Many directors’ tenure forcibly ends due to ethical violations or failed oversight, but in the case of those who voluntarily resign, many leave to work at a contracted foster care agency. For example, when Mentor was founded, its chief customer was Massachusetts Division of Youth Services (DYS), headed by Edward Murphy. Murphy soon abdicated that position to become chief executive officer (CEO) of Mentor (Roston and Singer-Vine 2015). Bruce Naradella took over for Murphy at Massachusetts DYS, before then also taking over for Murphy as CEO of Mentor (United States Securities and Exchange Commission 2018). In Los Angeles, David Sanders and Jackie Contreras, two DCFS directors within the past decade, both resigned to work at Casey Family Services, a private foster care provider (Casey Family Programs n.d.; Council of State Governments 2020). In fact, the current Casey CEO used to be commissioner of the New York ACS, and the executive vice president of Child and Family Services was executive director of the Colorado DHS (Casey Family Programs n.d.). In Georgia, over the last decade, two of the DCFS directors have left to work at private foster care agencies: Ron Scroggy at Together Georgia (Together Georgia 2017), and Virginia Pryor also at Casey (Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services n.d.).

Deflecting Criticism

Even without the suggestion of a “revolving door,” it seems clear that there is a desire of government leadership to deflect criticism, which at the very least suggests that officials are more concerned about their reputation than addressing welfare issues. In the Oklahoma audit, the reviewers stated, “there is evidence that senior managers have massaged these reports to make the numbers look better” (Miller 2011: 26), and that their quality control standards are monitored as to whether the reports “look like they will work” (Obradovic 2011: 3). In Los Angeles, an independent review reasoned that the DCFS’s extensively inconsistent classification of child deaths may be precipitated by incentives to deflect criticism (Office of Independent Review: Los Angeles County 2010). While the Los Angeles DCFS director said the inconsistencies were honest mistakes, a superior stated that “there are some reasons to believe that this is not just an accidental disconnect” (Zev Yaroslavsky: Los Angeles County Supervisor 2010). In 2015, a Texas judge presiding over the state foster care system ruled that the system was unconstitutional because it violated the 14th amendment right to be free from harm caused by the state (USDC: SDT 2015). Recently, the judge called the state’s inaction to improve the unconstitutional system “shameful” (Morris 2019). Further, with regard to its communication with her since 2015, she stated, “I cannot find DFPS [Department of Family and Protective Services] to be credible at any level” (ibid.). The judge is now choosing to rely only on court-appointed monitors to convey progress updates. Finally, former Georgia senator Nancy Schaefer has published public remarks stating: “I believe Child Protective Services nationwide has become corrupt and that the entire system is broken almost beyond repair. I am convinced parents and families should be warned of the dangers” (Schaefer 2007). She describes Georgia’s DCFS as a “protected empire” and refers to them as “the ‘Gestapo’ at work” (ibid.).

Limitations and Policy Implications

In sum, private foster care agencies contracted by the state are financially incentivized to keep children in their care, no matter if conditions are unsafe, rather than prepare the child for adoption. They exhibit rent-seeking behavior to win and maintain contracts, which extends their hold on the industry. Government agencies provide little oversight, which may encourage this behavior further. As predicted by public choice theory, officials are more strongly motivated to protect their reputations and develop their careers than to discipline these agencies. As a result, foster care adoption has suffered; the number of children waiting for adoption has increased by 25 percent since 2012, and only about half of the number of children waiting for adoption actually do get adopted each year (USCB 2019b).

It is important to recognize limitations of this work. First, a few other documented factors also contribute to why adoption has not been optimally supported. Demand from parents to adopt from foster care is somewhat limited by a mismatch of parental preferences and child characteristics (Baccara et al. 2010). Other negative factors include the increasing availability of Assistive Reproductive Technologies (Gumus and Lee 2010) and the stigma attached to adoption (Small 2013). Second, some flaws in the foster care adoption system are already well recognized, including the system fragmentation and the scarcity of resources devoted to providing adoption services and social work (Hansen and Hansen 2006). There is also mounting evidence that the subsidy rate is too low and increasing it would improve the adoption rate out of foster care (Hansen 2007; Duncan and Argys 2007; Argys and Duncan 2013). All of these factors are significant, and their roles should not be understated. To better guide the focus of child welfare reform, future work should be done to quantify the relevant significance of misaligned incentives as presented in this article compared to these other factors.

Third, while I have provided evidence from many different systems to indicate that these problems are ubiquitous, this is not to say that the identified problems occur everywhere. Some contracts may be more clearly stipulated or better enforced. Many private agencies may not exploit the system in the ways I have mentioned, and many children do end up in good homes with loving foster parents; my motivation is rather to show that in many cases the current system largely provides such opportunity for exploitation, which can and does occur. My hope is that this initial thesis will lead to more targeted future work, including exploration of these results within each state, so that needs specific to each state can be identified and addressed precisely. Regardless, it seems clear that governments should rebid contracts with clearly specified quality expectations (Blackstone and Hakim 2003), and payment structures should better emphasize performance quality and permanency outcomes, which has been successful in some regions (Rubin et al. 2007). Creating greater competition within the market, with the government submitting bids to compete with private providers (managed competition), may help promote better performance as well (Blackstone and Hakin 2003). Finally, revolving door restrictions need to be in place for chief officials at the government offices.

References

Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) (2012, 2014, 2016, 2018) Available at www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/afcars.

Adoption Exchange Association (n.d.) “About Adoption from Foster Care.” Adopt US Kids. Available at www.adoptuskids.org/adoption-and-foster-care/overview/adoption-from-foster-care.

Argys, L., and Duncan, B. (2013) “Economic Incentives and Foster Child Adoption.” Demography 50 (3): 933–54.

Baccara, M.; Collard-Wexler, A.; Felli, L.; and Yariv, L. (2010) “Gender and Racial Biases: Evidence from Child Adoption.” Centre for Economic Policy Research Working Paper No. 2921.

Baptist Children’s Homes (2016) “Family First Update: Please Call Washington and Pray.” Available at www.bchblog.org/post/2016/11/29/family-first-update-please-call-washington-and-pray.

Barth, R. P. (2002) “Institutions vs. Foster Homes: The Empirical Base for a Century of Action.” Chapel Hill, N.C.: Jordan Institute for Families, School of Social Work.

Barth, R. P.; Lee, C. L.; Wildfire, J.; and Guo, S. (2006) “A Comparison of the Governmental Costs of Long-Term Foster Care and Adoption.” Social Services Review 80 (1): 127–58.

Bernal, R.; Hu, L.; Moriguchi, C.; and Nagypal, E. (2007) “Child Adoption in the United States: Historical Trends and the Determinants of Adoption Demand and Supply, 1951–2002.” Working Paper. Available at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.700.14&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Bessen, J. (2016) “Accounting for Rising Corporate Profits: Intangibles or Regulatory Rents?” Boston University School of Law, Law & Economics Working Paper No. 16–18.

Bethmann, D., and Kvasnicka, M. (2012) “A Theory of Child Adoption.” Ruhr Economic Paper No. 342. Available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2084186.

Blackstone, E. A., and Hakim, S. (2003) “A Market Alternative to Child Adoption and Foster Care.” Cato Journal 22 (3): 485–94.

Blanes-i-Vidal, J.; Draca, M.; and Fons-Rosen, C. (2012) “Revolving Door Lobbyists.” American Economic Review 102 (7): 3731–48.

Casey Family Programs (n.d.) “Executive Team.” Casey Family Programs. Available at www.casey.org/who-we-are/executive-team.

CFUSS (Committee on Finance: United States Senate) (2017) An Examination of Foster Care in the United States and the Use of Privatization. Washington: Senate Finance Committee (October).

Children’s Bureau (2017) “Grounds for Involuntary Termination of Parental Rights.” Available at www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/groundtermin.pdf.

Cohen, J.E. (1986) “The Dynamics of the ‘Revolving Door’ on the FCC.” American Journal of Political Science 30 (4): 689–708.

Council of State Governments (2020) “Strategy 2020: Safely Reducing Foster Care by Half.” Council of State Governments. Available at www.csg.org/events/annualmeeting/policy_sessions_am09/policy2020_session.aspx.

County of Los Angeles, Department of Auditor-Controller (2017) “Department of Children and Family Services: Children’s Trust Fund Unit Review.” Los Angeles, Calif.: Department of Auditor-Controller (May).

County of Los Angeles, Department of Children and Family Services [DCFS] (2020) “Statement from the Department of Children and Family Services on ‘the Trials of Gabriel Fernandez’ Netflix Documentary Series.” Los Angeles, Calif.: Department of Children and Family Services (March).

County of Los Angeles, Department of Public Social Services (2016) “Department of Public Social Services: GAIN Case Management Services.” Los Angeles, Calif.: Department of Public Social Services (March).

Dake, L. (2019) “Out of State, Out of Mind.” Oregon Public Broadcasting (December 11).

Dozier, M.; Kaufman, J.; Kobak, R.; O‘Connor, T. G.; Sagi-Schwartz, A.; Scott, S.; Shauffer, C.; Smetana, J.; van IJzendoorn, M. H.; and Zeanah, C. H. (2014) “Consensus Statement on Group Care for Children and Adolescents: A Statement of Policy of the American Orthopsychiatric Association.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 84 (3): 219–25.

Dudley, S. E., and Brito, J. (2012) Regulation: A Primer. Arlington, Va.: Mercatus Center.

Duncan, B., and Argys, L. (2007) “Economic Incentives and Foster Care Placement.” Southern Economic Journal 74 (1): 114–42.

Federal Bureau of Investigation (2019) “Foster Care Agency Shut Down.” Federal Bureau of Investigation (September 24).

Grim, R., and Chavez, A. (2017) “Children Are Dying at Alarming Rates in Foster Care, and Nobody Is Bothering to Investigate.” The Intercept (October 18).

Gronbjerg, K. A.; Chen, T. H.; and Stagner, M. W. (1995) “Child Welfare Contracting: Market Forces and Leverage.” Social Services Review 69 (4): 583–613.

Gumus, G., and Lee, J. (2010) “The ART of Life: IVF or Child Adoption?” IZA Discussion Paper No. 4761. Bonn: IZA.

Gutowski, C. (2019) “DCFS Says Nonprofit Misused Taxpayer Dollars, Demands Repayment of $100K.” Chicago Tribune (June 5).

Hansen, M. E. (2006) “The Value of Adoption.” Working Paper No. 2006–15. Washington: American University, Department of Economics.

________ (2007) “Using Subsidies to Promote the Adoption of Children from Foster Care.” Journal of Family Economic Issues 28 (3): 377–93.

Hansen, M. E., and Hansen, B. A. (2006) “The Economics of Adoption of Children from Foster Care.” Child Welfare 85 (3): 559–83.

Hatcher, D. L. (2019) “Stop Foster Care Agencies from Taking Children’s Resources.” Florida Law Review Forum 71 (1): 104–12.

Joseph, B. (2015) “The Brief Life and Private Death of Alexandria Hill.” Mother Jones (February 26).

Kalil, A. (2014) “Proposal 2: Addressing the Parenting Divide to Promote Early Childhood Development for Disadvantaged Children.” Hamilton Project. Washington: Brookings Institution.

Kane, D. (2015) Report to the Governor and the General Assembly. Illinois. Office of the Inspector General: Illinois Department of Children and Family Services (January).

Krauskopf, J., and Chen, B. (2013) “Administering Services and Managing Contracts: The Dual Role of Government Human Services Officials.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 29 (3): 625–28.

Lamb, M. E. (2012) “Mothers, Fathers, and Circumstances: Factors Affecting Children’s Adjustment.” Applied Developmental Science 16 (2): 98–111.

Landes E. M., and Posner A. R. (1978) “The Economics of the Baby Shortage.” Journal of Legal Studies 7 (2): 323–48.

Ledesma, K. (n.d.) “Adopting from Foster Care.” Adoptive Families. Available at www.adoptivefamilies.com/how-to-adopt/foster-care-adoption/adopting-from-foster-care.

Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services (n.d.). “Virginia Pryor.” Available at https://dcfs.lacounty.gov/about/who-we-are/leadership/virginia-pryor.

Mass Inc. (n.d.) “Greg Torres.” Available at https://massinc.org/author/gregtorres.

Mentor Network (n.d.). “Executive Team: Maria McGee.” The Mentor Network. Available at www.thementornetwork.com/team-member/maria-mcgee.

Miller, A. (2020) “Adoption & Child Welfare Services in the US.” Industry Report 62411. IBISWorld. Available at www.ibisworld.com/united-states/market-research-reports/adoption-child-welfare-services-industry.

Miller, V. P. (2011) “A Review of the Oklahoma Department of Human Services’ Child Welfare Practices from a Management Perspective.” Independent review prepared for the plaintiffs in D.G. v. Henry. Available at www.childrensrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/2011–03-15_ok_miller_management_review_final.pdf.

Moriguchi, C. (2012) “The Evolution of Child Adoption in the United States, 1950–2010: Economic Analysis of Historical Trends.” Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, Discussion Paper Series A No. 572. Tokyo: Hitotsubashi University Repository.

Morris, A. (2019) “Judge Fines Texas $50K a Day over ‘Broken’ Foster Care System.” San Antonio Express News (November 5).

Obradovic, Z. (2011) “Report on the KIDS System: Review and Analysis.” Analysis prepared for the plaintiffs in D.G. v. Henry. Available at https://www.childrensrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/2011–03-15_ok_obradovic_kids_system_review_final.pdf.

Office of Independent Review: Los Angeles County (2010) Re: Status of Implementation of SB39: Current Challenges. Los Angeles, Calif. Department of Independent Review (August). Available at http://zevyaroslavsky.org/wp-content/uploads/dcfs-08–30-10-BOS-Ltr-DCFS-SB39-Report.pdf.

Peters, M. G. (2018) “DOI Report Finds the City Administration for Children’s Services Did Not Sufficiently Hold Foster Care Providers Accountable for Safety of Children in Their Care.” Report on the Administration for Children’s Services’ from the City of New York’s Department of Investigation. Available at www1.nyc.gov/assets/doi/reports/pdf/2018/Oct/ACS_Rpt_Release_Final_10122018.pdf.

Reeves, R. V., and Howard, K. (2013) “The Parenting Gap.” Brookings Institution Report, Center on Children and Families. Available at www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/09-parenting-gap-social-mobility-wellbeing-reeves.pdf.

Reynolds, D. (2017) “Ohio Foster Care System Flooded with Children Amid Opioid Epidemic.” CBS News (August 7).

Richardson, D., and Memmott, K. (2018) “Foster Care in Oregon: Chronic Management Failures and High Caseloads Jeopardize the Safety of Some of the State’s Most Vulnerable Children.” Oregon Audits Division, Report No. 2018-05. Available at https://sos.oregon.gov/audits/Documents/2018–05.pdf.

Roca (n.d.). “Board of Directors: Dwight Robson.” Roca. Available at https://rocainc.org/team/dwight-robson.

Roston, A. (2015) “‘Culture of Incompetence’: For-Profit Foster-Care Giant Is Leaving Illinois.” BuzzFeed News (April 17).

________ (2016) “Foster Care Company’s ‘Abnormal Level of Lobbying.’” BuzzFeed News (January 12).

Roston, A., and Singer-Vine, J. (2015) “Fostering Profits: Abuse and Neglect at America’s Biggest For-Profit Foster Care Company.” BuzzFeed News (February 20).

Rubin, D. M.; O’Reilly, A. L. R.; Luan, X.; and Localio, A. R. (2007) “The Impact of Placement Stability on Behavioral Well-Being for Children in Foster Care.” Pediatrics 119: 336–44.

Schaefer, N. (2007) “The Corrupt Business of Child Protective Services.” Available at http://fightcps.com/pdf/thecorruptbusinessofchildprotectiveservices.pdf.

Shatzkin, K. (2015) “Every Kid Needs a Family: Giving Children in the Child Welfare System the Best Chance for Success.” Annie E. Casey Foundation, Policy Brief.

Small, J. (2013) “Adopted in America: A Study of Stigma.” Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=2280517.

Stein, J. (2016) “Three Arrested as City DOI Releases Scathing Report on Close to Home Oversight.” NYNMEDIA (April 14).

Tabakovic, H., and Wollmann, T. G. (2018) “From Revolving Doors to Regulatory Capture? Evidence from Patent Examiners.” NBER Working Paper No. 24638. Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Taylor Adams, L. (2014) “Legal Orphans Need Attorneys to Achieve Permanency.” American Bar Association (December 1).

Therolf, G. (2008) “Low-Rated Firm Fights to Keep Rich County Work.” Los Angeles Times (October 30).

Thornberry, T. P.; Smith, C. A.; Rivera, C.; Huizinga, D.; and Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (1999) “Family Disruption and Delinquency.” Available at www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/178285.pdf.

Together Georgia (2017) “Former TG Director, Ron Scroggy, Receives Big Voice Award.” Together Georgia (September 6).

United States District Court: Southern District of Texas (USDC: SDT) (2015) Memorandum Opinion and Verdict of the Court in “M.D. et al. v. Abbott et al,” entered on December 17. Available at https://cases.justia.com/federal/district-courts/texas/txsdce/2:2011cv00084/876792/368/0.pdf?ts=1450456518.

United States Securities and Exchange Commission (2018) “Civitas Solutions, Inc.” Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14 (a) of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934. Available at www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1608638/000160863818000003/fy17proxy.htm.

USCB (U.S. Children’s Bureau) (2019a) “Adoption and Foster Care Reporting System (AFCARS) Report No. 26.” Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families.

________ (2019b) “Trends in Foster Care and Adoption: FY 2009–FY 2018.” Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families.

USDHHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) (2008) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. “Preparing Effective Contracts in Privatized Child Welfare Systems.” Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (August 30).

Wiltz, T. (2019) “The Feds Are Cutting Back on Group Homes. Some Say That’s a Big Mistake.” Pew Charitable Trusts (July 8). Available at www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2019/07/08/the-feds-are-cutting-back-on-foster-group-homes-north-carolina-says-thats-a-big-mistake.

Wulczyn, F.; Alpert, L.; Martinez, Z.; and Weiss, A. (2015) “Within and Between State Variation in the Use of Congregate Care.” Report for the Center for State Child Welfare Data, University of Chicago (June).

Zev Yaroslavsky: Los Angeles County Supervisor (2010) “Secret Child-Death Records to Be Revealed.” Zev Yaroslavsky (August).

Zill, N. (2011) “Adoption from Foster Care: Aiding Children While Saving Public Money.” Brooking Institution, Center for Children and Families Brief No. 43 (May).

Zullo, R. (2002) “Private Contracting of Out-of-Home Placements and Child Protection Case Management Outcomes.” Child and Youth Services Review 24 (8): 583–600.

________ (2008a) “Child Welfare Privatization and Child Welfare: Can the Two Be Efficiently Reconciled?” Ann Arbor, Mich.: Labor Studies Center, University of Michigan.

________ (2008b) “Is Social Service Contracting Coercive, Competitive, or Collaborative?” Administration in Social Work 30 (3): 25–42.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.