Akerlof, G. (1970) “The Market for Lemons: Quantitative Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 84: 488–500.

Aoki, M. (2001) Toward a Comparative Institutional Analysis. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Bank for International Settlement (BIS) (2019) BIS Quarterly Review (December). Basel, Switzerland: BIS.

Campbell, T., and Kracaw, W. A. (1980) “Information Production, Market Signalling, and the Theory of Financial Intermediation.” Journal of Finance 35: 863–82.

Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR (2020) Hong Kong Monthly Digest of Statistics (June).

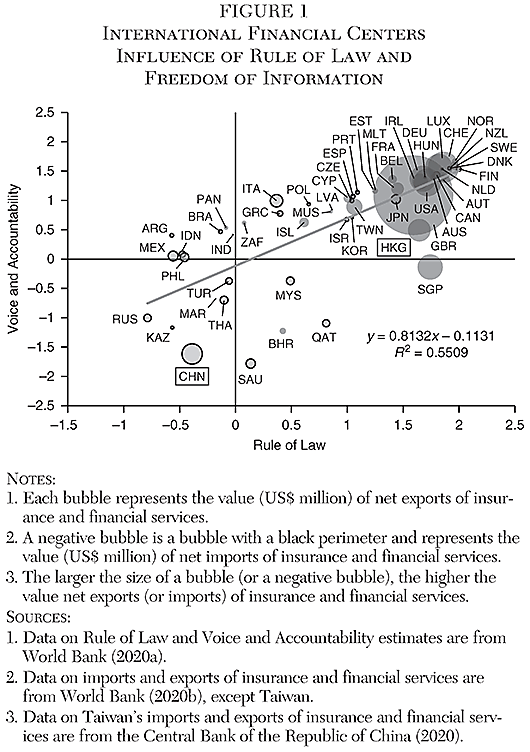

Central Bank of the Republic of China (2020) National Statistics, Republic of China. Available at https://eng.stat.gov.tw/mp.asp?mp=5.

Chu, K. H. (1999) “Free Banking and Information Asymmetry.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 31: 748–62.

Diamond, D. (1984) “Financial Intermediation and Delegated Monitoring.” Review of Economic Studies 51: 393–414.

Dorn, J. A. (1998) “China’s Future: Market Socialism or Market Taoism?” Cato Journal 18 (1): 131–46.

________ (2019) “China’s Future Development: Challenges and Opportunities.” Cato Journal 39: 173–88.

Gilroy, T.; Owens, I.; and Tovar, A. (2020) “President Trump Signs into Law the Hong Kong Autonomy Act.” SanctionsNews, BakerMcKenzie blog (July 14). Available at https://sanctionsnews.bakermckenzie.com/president-trump-signs-into-law-the-hong-kong-autonomy-act.

Hanson, D. (2012) “Positive Non-Interventionism: The Policy that Unleashed Hong Kong.” AEIdeas (March 22).

Hayek, F. A. (1937) “Economics and Knowledge.” Economica 4 (13): 33–54.

________ (1940) “Socialist Calculation: The Competitive ‘Solution.’” Economica 7 (26): 125–49.

________ (1944) The Road to Serfdom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

________ (1945) “The Use of Knowledge in Society.” American Economic Review 35 (4): 519–50.

________ (1960) The Constitution of Liberty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

________ (1967a) “The Result of Human Action but Not of Human Design.” In Studies in Philosophy, Politics and Economics, 96–105. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

________ ([1955] 1967b) “Degrees of Explanation.” In Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, 3–21. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

________ ([1964] 1967c) “The Theory of Complex Phenomena.” In Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, 22–42. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

________ (1973) Law, Legislation and Liberty. Volume I: Rules and Order. London: Routledge.

________ (1978a) “Competition as a Discovery Procedure.” In New Studies in Philosophy, Politics, Economics and the History of Ideas, 179–90. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

________ (1978b) Denationalization of Money: The Argument Refined. London: Institute of Economic Affairs.

________ (1988) The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Heritage Foundation (2020) Miller, T.; Kim, A. B.; and Roberts, J. M. (eds.), 2020 Index of Economic Freedom. Washington: Heritage Foundation.

Hicks, J. R. (1969) A Theory of Economic History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hu, X. (2020) “Pompeo Makes Arrogant, Hysterical Statements about HK Autonomy.” Global Times (May 28).

Huang, Y., and Ge, T. (2019) “Assessing China’s Financial Reform: Changing Roles of the Repressive Financial Policies.” Cato Journal 39: 65–85.

Jao, Y. C. (1997) Hong Kong as an International Financial Centre: Evolution, Prospects, and Policies. Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press.

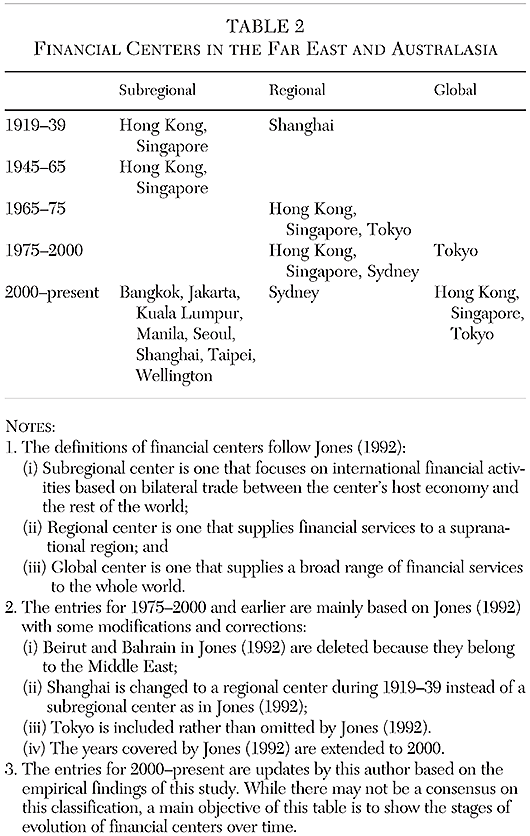

Jones, G. (1992) “International Financial Centers in Asia, the Middle East, and Australia: A Historical Perspective.” In Y. Cassis (ed.), Finance and Financiers in European History, 1880–1960, 405–28. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kirzner, I. (1984) “Economic Planning and the Knowledge Problem.” Cato Journal 4 (2): 407–18.

Leland, H. E., and Pyle, D. H. (1977) “Information Asymmetries Financial Structure, and Financial Intermediation.” Journal of Finance 32: 371–81.

McCarthy, I. (1979) “Offshore Banking Centers: Benefits and Costs.” Finance and Development 16: 45–48.

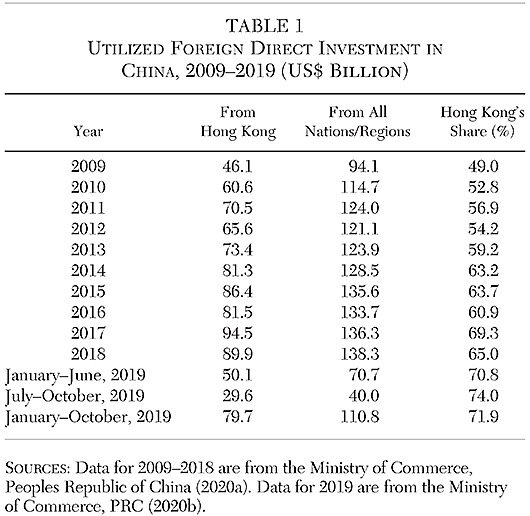

Ministry of Commerce, People’s Republic of China (2020a) Statistical Bulletin of FDI in China 2019.

________ (2020b) News Release of National Assimilation of FDI, various issues. Available at http://mofcom.gov.cn.

Mises, L. V. ([1920] 1990) Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth. Auburn: Ludwig von Mises Institute.

O’Driscoll, Jr., G. P. (1994) “An Evolutionary Approach to Banking and Money.” In J. Birner and R. Zijp (eds.), Hayek, Co-ordination and Evolution: His Legacy in Philosophy, Politics, Economics, and the History of Ideas, 126–40. London: Routledge.

White House (2020) “The President’s Executive Order on Hong Kong Normalization” (July 14). Available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/presidents-executive-order-hong-kong-normalization.

Wong, D. (2020) “Hainan FTZ Masterplan Released to Establish China’s Biggest Free Trade Port by 2035.” China Briefing, Dezan Shira & Associates (June 5).

World Bank (2020a) Worldwide Governance Indicators Database. Washington: World Bank. Available at https://databank.worldbank.org/source/worldwide-governance-indicators.

(2020b) World Development Indicators Database. Washington: World Bank. Available at https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

Yeager, L. B. (1994) “Mises and Hayek on Calculation and Knowledge.” Review of Austrian Economics 7 (2): 93–109.

Z/Yen Group (2020) Global Financial Centres Index 27, and also reports in previous years since 2008. London: Long Finance.