Donald Trump was a trade “hawk” long before he became president. In the late 1980s, he went on the Oprah Winfrey show and complained about Japan “beating the hell out of this country” on trade (Real Clear Politics 2019). As president, he has continued with the same rhetoric, using it against a wide range of U.S. trading partners, and he has followed it up with action (often in the form of tariffs).

While many countries have found themselves threatened by Trump’s aggressive trade policy, his main focus has been China. As a result, the United States and China have been engaged in an escalating tariff, trade, and national security conflict since July 2018, when the first set of U.S. tariffs on China went into effect and China retaliated with tariffs of its own.

In this article, we explore the U.S.-China economic conflict, from its origins to the trade war as it stands today. We then offer our thoughts on where this conflict is heading and when it might end.

U.S.-China Trade Relations in the Pre-Trump Era

China was an original signatory of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the multilateral trade agreement that came into force in 1948. A year later, however, the Communist Party of China came to power and established the People’s Republic of China, with the government of the Republic of China retreating to Taiwan. Soon after, the Republic of China notified the GATT of China’s withdrawal (Gao 2007).

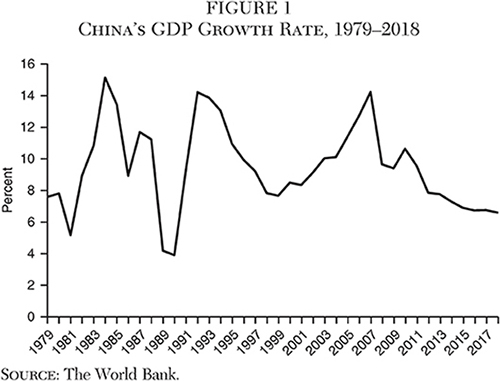

After several decades of heavy state intervention under Mao, in 1978 Deng Xiaoping began his push for economic reforms in the People’s Republic, including state-owned enterprise reform, private enterprise development, and the “household contract responsibility system” in rural areas. With this liberalization in place, economic growth and industrial development took hold quickly. As illustrated in Figure 1, China’s GDP has grown at a steady pace, with certain fluctuations, since 1979.

As part of its liberalization efforts, China began to develop formal economic relationships with the rest of the world. Starting in the 1980s, it negotiated bilateral investment treaties with a wide range of countries, and in 1982, it obtained observer status at the GATT. China submitted its application for GATT membership in 1986. Over a period of 15 years, it conducted bilateral negotiations with 37 GATT/WTO members, and concluded the negotiation with the United States, one of the toughest, in 1999 (see USTR 2001).

China’s WTO Accession and Economic Rise

As part of its accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), China made a series of commitments to open its market, including lowering tariffs on goods, limiting subsidies for agricultural products, strengthening intellectual property protection, and opening some of its services markets. In addition to agreeing to these basic obligations under various WTO agreements, China made some additional commitments in its Accession Protocol. For instance, China committed to forgo the special and differential treatment granted to developing countries in some areas; it made additional commitments related to transparency, judicial review, national treatment of foreign investors, economic reform, and compliance review; and finally, it agreed to accept treatment as a nonmarket economy in antidumping proceedings for 15 years, which meant it would be subject to a more onerous calculation methodology (Qin 2003).

China’s WTO accession was mainly negotiated during the Clinton era, but the first president to have to deal with China as a WTO member was George W. Bush. China’s economy had already been growing quickly in the pre-WTO era, and its rise continued after entry into the WTO. The continued high growth and the shift to production of more sophisticated industrial products put Chinese companies in competition with American companies to a degree not seen before. The Bush administration faced a difficult decision on how to respond.

Trade journalist Paul Blustein (2019) describes the Bush administration’s trade policy response as “sluggish,” and says: “It is reasonable to wonder why a more forceful approach wasn’t taken.” He offers the following explanations for why more was not done about Chinese trade practices that violated the letter or spirit of WTO rules: optimism that China would continue moving toward freer markets on its own; fear of a U.S.-China trade war; U.S. companies were making money in China and wanted to avoid disruptions, and thus did not complain much; the administration needed Chinese support on its “anti-terrorism” policies; and finally, the global financial crisis weakened the ability of the Bush administration to make demands.

In terms of actions not taken, Blustein focuses on the Bush administration’s rejection of domestic industry complaints under Section 421, which provides for a product-specific “safeguard” tariff/quota on Chinese imports. But there is also the possibility of WTO complaints, which the administration was slow to pursue at first, although the complaints picked up in later years: one complaint in 2004, one in 2006, three in 2007, and two in 2008. According to U.S. trade officials from this era, there was a sense initially that China deserved a chance to settle in at the WTO before complaints were brought. By 2005, it was clear that complaints were needed. However, U.S. companies were not pressing the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) to bring claims, and without the evidence they could provide, the cases were unlikely to be successful. As a result, cases emerged slowly.

The Bush administration also found a diplomatic way to press forward, with an approach called the Strategic Economic Dialogue and the Senior Dialogue. This led to some minor successes, but when the financial crisis hit in 2008, the administration became consumed with domestic issues and was not in a position to make demands of China.

Obama’s TPP Strategy

President Obama took office in the middle of that financial crisis, and his initial focus was on domestic policy. Eventually he turned to trade and foreign policy, however, and Asia and China were a big part of that. Obama’s “pivot to Asia” involved giving greater prominence to the Pacific region, with the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) as a key element. The TPP has several goals, but one of them was to respond to China’s rise.

President Obama himself explained how he saw TPP as targeting China:

[The TPP] would give us a leg up on our economic competitors, including China. As we speak, China is negotiating a trade deal that would carve up some of the fastest-growing markets in the world at our expense, putting American jobs, business and goods at risk.… America should write the rules. America should call the shots. Other countries should play by the rules that America and our partners set, not the other way around.… The United States, not China, should write them [Obama 2016].

While Obama and others in his administration spoke mostly of “writing the rules,” many commentators emphasized that the TPP would “contain” China. As law professor Daniel Chow put it: “The U.S. led the TPP negotiations and deliberately excluded China from the negotiations. This ploy by the U.S. was a calculated effort to contain China and to shift power in trade in the Asia-Pacific from China to the U.S. China now appears to face a difficult choice” (Chow 2016). And others noted that, “Washington’s words are all about constructive engagement, but its deeds mostly smack of containment” (Naughton et al. 2015).

The characterization of the TPP as “containment” or simply a competition over rule-writing is perhaps more about rhetoric than reality, and presumably there were different views within the administration about the purpose in relation to China. Regardless of its true purpose, however, the U.S. involvement in TPP ended when domestic politics got in the way of congressional passage, so its potential impact on China as a U.S.-led initiative is unknown (other TPP parties are going forward with the agreement).

In addition to the TPP as a way to address concerns with China, the Obama administration imposed tariffs on Chinese tires under Section 421. It was also a frequent user of the WTO dispute settlement mechanism: during his eight years in office, his administration brought 14 complaints against China.

At the same time, the Obama administration also tried to engage with China through negotiations. It continued the bilateral negotiating approach started by the Bush administration, replacing the Strategic Economic Dialogue and Senior Dialogue with the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue. The Obama administration also carried out a bilateral investment treaty negotiation with China, but the talks were never completed.

The Trump Era

That brings us to the Trump era, which has certainly seen some aggressive tactics against China, although perhaps not effective ones. Trump once declared that he was the “chosen one” to take on China (Breuninger 2019), and he asserts that past U.S. administrations have been weak in this regard (Phillips 2017). As seen above, that is not entirely true, and we may not find out what actually works in relation to promoting liberalization in China until a future administration. Trump’s tactics may be tough, but it is not clear that they will work.

Bilateral trade talks began soon after President Trump took office. (During his campaign he had promised that the trade deficit with China would be high on his priority list if elected.) The initial result was the so-called 100-Day Action Plan, the results of which were announced in May 2017 (see U.S. Department of Commerce and Department of the Treasury 2017). The plan covered issues such as China’s purchases of U.S. agricultural products and the opening of China’s financial services market. However, the limited outcomes and economic impact of the plan were overtaken by the quick escalation of the trade war that came soon after.

Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 authorizes the U.S. Trade Representative’s Office to investigate and take action against unfair trade practices by trading partners, including practices that violate trade agreements, are “unjustifiable” and “burden or restrict U.S. commerce,” or are “unreasonable or discriminatory” and “burden or restrict U.S. commerce.” The Trump administration launched a Section 301 investigation into certain Chinese trade practices in August 2017. After eight months of investigating, USTR found that China’s laws and policies had harmed U.S. economic interests in the following ways:

- “China uses joint venture requirements, foreign investment restrictions, and administrative review and licensing processes to require or pressure technology transfer from U.S. companies;

- “China deprives U.S. companies of the ability to set market-based terms in licensing and other technology-related negotiations;

- “China directs and unfairly facilitates the systematic investment in, and acquisition of, U.S. companies and assets to generate large-scale technology transfer;

- “China conducts and supports cyber intrusions into U.S. commercial computer networks to gain unauthorized access to commercially-valuable business information.”1

- Drop the trade wars with U.S. allies;

- Liberalize trade with those allies to put economic pressure on China;

- Work with those allies in a coordinated effort to press China to liberalize, including filing WTO complaints against China and negotiating with China in a good faith manner (and being willing to make concessions of our own so that China can present the deal as a balanced one).

As a response to these practices, President Trump announced the imposition of tariffs on Chinese imports. In reaction, China retaliated with tariffs of its own. Since then, the two sides have continued to escalate the rates and product coverage, and of this writing U.S. products exported to China are now facing 21.1 percent tariffs on average (compared to an average of 6.7 percent applied to products from other nations). Similarly, Chinese goods are subject to a 21 percent tariff on average in the U.S. market (as compared to the 3.1 percent average U.S. tariff rate that applied prior to all of the Trump administration’s recent tariffs) (see Bown 2019a, 2019b).

The tariffs have reduced bilateral trade significantly. But the reduction in bilateral trade with China does not mean that jobs are coming back to the United States. Instead, imports from China have been replaced with imports from other countries. China has dropped from the largest trading partner of the United States to the third largest, having been surpassed by Mexico and Canada. European countries, Japan, South Korea, and Vietnam have also witnessed a surge in trade with the United States. For instance, Vietnam’s exports to the United States grew 33 percent in the first half of 2019 (Kiernan and DeBarros 2019).

The U.S.-China trade negotiations have continued, but the talks have produced only limited results so far. At the beginning, the Trump administration focused on trade deficit reduction, technology and intellectual property (IP) protection, subsidies, tariff reduction, services, investment, and implementation (Rabinovitch 2018). China, in return, asked for a number of items, including market access in government procurement, opening the e‑payment market, recognizing China’s market-economy status, and lifting the export ban on sales to ZTE (Curran and Zhai 2018).

In early 2019, there was some hope that an agreement could be reached on certain issues. However, the talks broke down in May 2019 after the Trump administration accused China of “backtracking” (Lawder, Mason, and Martina 2019). Since then, talks have been focused on a narrow subset of issues, as it became difficult to resolve all issues at once. On October 11, 2019, USTR announced an agreement in principle on a “phase one” deal, and a final deal was announced in December, with a fact sheet giving general details. The agreement was to be signed in January, with the legal text released some time thereafter (Brunnstrom and Spetalnick 2019). The “phase one” deal covered China’s commitment to purchase U.S. goods and services, intellectual property protection and technology transfer, agricultural nontariff barriers, currency issues, China’s financial services market, and a dispute process (Shalal and Lawder 2019).

It is important to keep in mind that Trump has not imposed tariffs only on China. If his aggressive trade actions had only targeted China, they might have worked better and his claims about Chinese trade practices might be taken more seriously. Instead, though, Trump has imposed and threatened tariffs on many countries, including close allies. Most famously, the Trump administration has launched five investigations related to the impact of imports on national security (Section 232 investigations). Two of them, on steel and aluminum, have led to tariffs being imposed on a wide range of countries, including China. (Some countries have been able to secure exemptions from these tariffs with the exemptions usually tied to bilateral agreements with the Trump administration.) This approach suggests that perhaps his concern about China is not as high a priority as it sometimes sounds, and the issues with China could be settled through a bilateral trade deal as well. Indeed, his general skepticism about trade liberalization may be undermining his efforts to take on China, which might go better in a coordinated approach with others.

What Does the Future Hold?

The “phase one” deal will not be the end of the story. The Trump administration expects a continuation of trade talks, as “phase two” or even “phase three.” The subsequent trade talks could cover China’s opening of nonfinancial services markets (possibly telecommunications) and forced technology transfer (Shalal and Lawder 2019). China’s industrial policy, subsidies, and data regulations are other issues that have drawn strong criticism in the United States. It is unclear whether all of them will be raised or agreed upon. The two sides remain far apart on most of them, and any deadlock in negotiations may result in more tariffs and other punitive actions by both sides.

In addition to a tariff war, the Trump administration and Congress have taken various other actions related to economic relations with China aimed at tightening rules on both investment and trade, including on data and technology. China has said that it would like to address these issues in negotiations. Both sides will face constraints in reaching a deal, though. For its part, China is in a position where it does not have many options, as its economy has been harmed by the trade war. However, any appearance of caving in to apparent U.S. bullying will be politically harmful for the Chinese leadership. On the other side, President Trump does not seem willing to compromise on the core trade issues (perhaps he is more willing on certain technology issues), but even if he were, Congress is pressing for even stronger actions in some areas.

There is probably greater hope with a future Democratic administration. Congressional concern with China is strong, so whoever is president in the future will not be able to ignore the trade concerns with China. But a Democratic president will have an incentive to change strategies. If the goal is to push China to liberalize, the Trump strategy has not been working. A Democrat could consider a different approach, with the following components:

Conclusion

There has been a lot of talk recently about a “decoupling” of the U.S. and Chinese economies, as well as the possibility of a new “cold war” between the countries. The economic and political consequences of such a development would be disastrous. As long as Trump is president, the trade war is likely to stay where it is or escalate. Under a future administration, however, there are options to deescalate and to push China to take on greater responsibility (i.e., liberalize more) in the international trading system.

References

Blustein, P. (2019) “The Untold Story of How George W. Bush Lost China.” Foreign Policy (October 2).

Bown, C. P. (2019a) “US-China Trade War: The Guns of August.” Washington: Peterson Institute for International Economics (September 20).

_________ (2019b) “US-China Trade War Tariffs: An Up-to-Date Chart.” Washington: Peterson Institute for International Economics (October 11).

Breuninger, K. (2019) “‘I Am the Chosen One,’ Trump Proclaims as He Defends Trade War with China.” CNBC (August 21).

Brunnstrom, D., and Spetalnick, M. (2019) “U.S.-China Trade Deal Signing Could Be Delayed to December; London a Possible Venue–Source.” Reuters (November 6).

Chow, D. C. K. (2016) “How the United States Uses the Trans-Pacific Partnership to Contain China in International Trade.” Chicago Journal of International Law 17 (2): 370–402.

Curran, E., and Zhai, K. (2018) “Here’s What the U.S., China Demanded of Each Other on Trade.” Bloomberg (May 4).

Gao, H. (2007) “China’s Participation in the WTO: A Lawyer’s Perspective.” Singapore Year Book of International Law 11: 41–74.

Kiernan, P., and DeBarros, A. (2019) “Tariff Fight Knocks Off China as Top U.S. Trading Partner.” Wall Street Journal (August 2).

Lawder, D.; Mason, J.; and Martina, M. (2019) “China Backtracked on Almost All Aspects of U.S. Trade Deal–Sources.” Reuters (May 8).

Naughton, B.; Kroeber, A. R.; De Jonquières, G.; and Webster, G. (2015) “What Will the TPP Mean for China?” Foreign Policy (October 7).

Obama, B. (2016) “President Obama: The TPP Would Let America, Not China, Lead the Way on Global Trade.” Washington Post (May 2).

Phillips, T. (2017) “Trump Praises China and Blames US for Trade Deficit.” The Guardian (November 9).

Qin, J. Y. (2003) “WTO-Plus Obligations and Their Implications for the World Trade Organization Legal System: An Appraisal of the China Accession Protocol.” Journal of World Trade 37 (3):483–522.

Rabinovitch, S. (2018) Twitter (May 4): https://twitter.com/S_Rabinovitch/status/992324675857362944.

Real Clear Politics (2019) “Donald Trump to Oprah in 1988: America a Debtor Nation, ‘Something Is Going to Happen.’” Real Clear Politics blog (July 29).

Shalal, A., and Lawder, D. (2019) “U.S., Chinese Teams Working on Phase 1 Trade Deal Text: Mnuchin.” Reuters (October 16).

U.S. Department of Commerce and Department of the Treasury (2017) “Initial Results of the 100-Day Action Plan of the U.S.-China Comprehensive Economic Dialogue.” Joint Press Release (May 11).

USTR (U.S. Trade Representative) (2001) “USTR Releases Details on U.S.-China Consensus on China’s WTO Accession.” Washington: USTR (June 14).

_________ (2018) “Findings of the Investigation into China’s Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974.” Washington: USTR (March 22).

1 USTR, Section 301 Investigation Fact Sheet. See also, USTR (2018).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.