The ratcheting up of tariffs and the Fed’s discretionary conduct of monetary policy are a toxic mix for economic performance. Escalating tariffs and President Trump’s erratic and unpredictable trade policy and threats are harming global economic performance, distorting monetary policy, and undermining the Fed’s credibility and independence.

President Trump’s objectives to force China to open access to its markets for international trade, reduce capital controls, modify unfair treatment of intellectual property, and address cybersecurity issues and other U.S. national security issues are laudable goals with sizable benefits. However, the costs of escalating tariffs are mounting, and the tactic of relying exclusively on barriers to trade and protectionism is misguided and potentially dangerous.

The economic costs to the United States so far have been relatively modest, dampening exports, industrial production, and business investment. However, the tariffs and policy uncertainties have had a significantly larger impact on China, accentuating its structural economic slowdown, and are disrupting and distorting global supply chains. This is harming other nations that have significant exposure to international trade and investment overseas, particularly Japan, South Korea, and Germany. As a result, global trade volumes and industrial production are falling. Weaker global growth is reflected in a combination of a reduction in aggregate demand and constraints on aggregate supply.

The Federal Reserve has achieved its dual mandate, yet it has resumed monetary easing, cutting its policy rate in July, September, and October in response to perceived downside risks associated with trade policy uncertainties. Combined with President Trump’s inappropriate public pressure on the Fed to cut rates, the Fed’s heightened focus on uncertainties and diminished reliance on data dependence increases the risks of a policy mistake that may undercut its public credibility and independence. The rate cuts will have little if any impact in offsetting the negative supply constraints of the tariffs and policy uncertainties on investment and productive capacity. However, by reducing the buffer from the zero lower bound (ZLB), they reduce the Fed’s flexibility to implement effective countercyclical policy in response to a future economic downturn.

The history of tariffs and the ebbs and flows of globalization provide critical lessons and caution about the significant downside risks of the current thrust of U.S. trade policies. The recent era of globalization may have already begun to fade, and the current reemergence of tariffs—imposed primarily by the United States, but also other nations—and tighter immigration laws are accentuating this drift toward protectionism.

In the face of an escalation of trade barriers, the Fed must continue to pursue its dual mandate but not extend monetary policy beyond its capabilities. The Fed should make clear that escalating trade barriers and policy uncertainties that impose supply constraints on productive capacity and distort global supply and distribution channels are beyond the scope of monetary policy to remedy. It must also emphasize the importance of it being independent to conduct policy without political interference or pressure and should rebuff inappropriate pressures from the administration while maintaining its politically neutral stance.

Escalating Tariffs and Their Economic Costs

While campaigning for the U.S. presidency, Donald Trump railed against the current world trade order and touted “America First” with a tilt toward protectionism. These two themes have become a reality, highlighted by disruptions to existing trade agreements and a wave of escalating tariffs, particularly aimed at China. In 2017, President Trump’s primary policy thrusts were aimed at easing burdensome regulations and tax cuts and reform. Economic performance improved decidedly. Beginning in late 2017, President Trump began ramping up tariffs. Most of the tariffs have been imposed without explicit approval of Congress, based on the administration’s interpretation of existing legislation that either protects industries from imports or addresses foreign trade behavior (particularly of China) that is perceived to be unfair, threatens national security, or is considered a national emergency.

President Trump’s preference for tariffs is driven by a combination of beliefs. He dislikes bilateral trade deficits, despite the fallacy that bilateral trade deficits impose economic costs, and tilts toward mercantilism. Trump distrusts China—its ideology, its policies, and its strengthened economic position—and perceives it as a threat to U.S. supremacy and security. Anecdotal evidence of China’s theft of U.S. intellectual property is abundant. Trump distrusts globalism and the established governmental channels for conducting diplomacy and is skeptical—with good reason—of the efficacy of the World Trade Organization (WTO) for conflict resolution of violations of international trade law and enforcement of unfair trade practices. Rather, President Trump eschews establishment protocols and favors rough and tumble one-on-one negotiating.

A chronology of the Trump administration’s trade policies (i.e., the tariffs and other barriers to trade, administrative rationale, and threats) highlights the clear escalation and broadening use of tariffs and foreign retaliation—beginning with solar panels and washing machines (January 2018), steel and aluminum (March 2018), chinaware (March 2018 to present), and automobiles (Chudik 2019; Fajgelbaum et al. 2019). To date, tariffs have been increased on over $300 billion of imports, primarily imports from China, but also imports from Japan, South Korea, Canada, and Mexico (Varas 2019). Trading partners have retaliated with over $110 billion of tariffs on goods and services imported from the United States (Amiti, Redding, and Weinstein 2019). These imposed tariffs have been interspersed with threats of more tariffs and disruptions, back peddling, and adjustments that have heightened uncertainty about future trade policies (Bown and Irwin 2019).

Several of President Trump’s public statements stand out. In March 2018, immediately after imposing tariffs on aluminum and steel imports, the president stated: “Trade wars are good, and easy to win.” The subsequent escalation of tariffs seems to reflect a miscalculation that China would be more willing to negotiate than actually has been the case. As U.S. negotiations with China extended far beyond trade to include issues of treatment of intellectual property, cybersecurity, cross-border investment and financial policies, and national security issues, President Trump’s December 2018 statement, “I am a tariff man,” highlights his preference for imposing tariffs as a lever for achieving other foreign objectives, despite their economic costs. Like many historic diplomatic skirmishes, this one has escalated, and both China and the United States face difficult issues. China’s potential economic growth is slowing independently of the tariffs and dragging down global economies, and its leaders face many economic, financial, and noneconomic issues that complicate the path to resolution. While President Trump has fairly wide bipartisan support for his longer-run objectives with China, his punishing tactics are harming the U.S. economy. Moreover, businesses identify trade-policy uncertainty as a key factor that is inhibiting expansion plans. Until a U.S.-China agreement on trade policies is reached, economic performance will suffer.

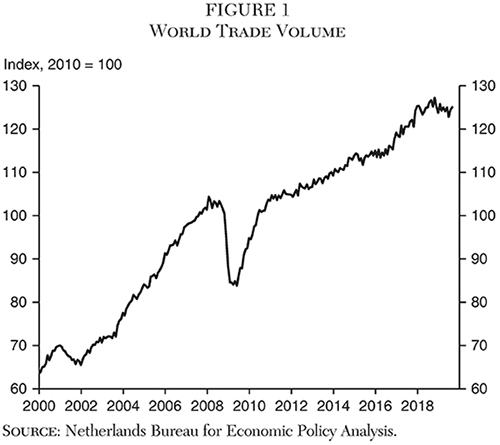

To date, the negative effects on the U.S. economy have been moderate but are more pronounced on global performance. The negative effects of policy-related uncertainties on trade, industrial production, and investment have been as large if not larger than the direct impacts of the tariffs. This is most apparent in declining global trade volumes and industrial production, disruptions to global supply chains, loss in business confidence, and widespread anecdotal evidence (Figure 1).

Conventional trade models find that tariffs have increased the costs of U.S. imported goods, imposing burdens on U.S. manufacturers and their production chains, and raising costs to consumers. Amiti, Redding, and Weinstein (2019) find that tariffs have increased the cost of U.S. manufacturing by 1 percent and are forcing a reorganization of global supply chains. Fajgelbaum et al. (2019), using a model that estimates the impact of targeted tariffs on imports and exports, find reduced import volumes, complete pass-through to prices paid by U.S. importers, and sizable reduction in U.S. exports. They estimate the net impact on U.S. GDP is 0.4 percent. A sustained drag on business investment reduces the capital stock and lowers productive capacity and potential growth.

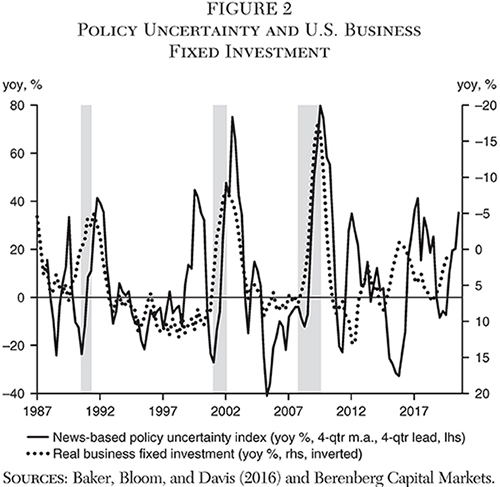

The heightened uncertainty related to economic policy weighed heavily on business decisions and economic performance. Using the economic policy uncertainty index developed by Baker, Bloom, and Davis (2016), we find a simple 49 percent correlation with U.S. business investment (Figure 2). The recent flattening in business investment and declines in exports and industrial production are not surprising in light of the spike in the economic policy uncertainty stemming from the erratic ramping up of tariffs.

More rigorous empirical research, based on different measures of policy uncertainty, finds large impacts on business activity. Based on a World Trade Uncertainty (WTU) Index, derived from the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) country reports, Ahir, Bloom, and Furceri (2019) estimated that the jump in their WTU index beginning in 2017 through the first quarter of 2019 reduced global growth by up to 0.75 percentage points in 2019. Using a measure of trade uncertainty aggregated over the European Union, the United States, China, and the United Kingdom based on text-mining techniques, Ebeke and Siminitz (2018) estimate that the investment-to GDP ratio in the Eurozone is on average 0.75 percentage points lower for five quarters following a one-standard deviation increase in the level of trade uncertainty. They find that the negative impacts of policy uncertainty are much larger for nations that rely more heavily on tradable goods.

In a recently released study, researchers at the Federal Reserve Board developed different measures of trade policy uncertainty—one on a firm level and two based on aggregate indicators for the U.S. economy using newspaper coverage and data volatility on import tariffs (Caldara et al. 2019). They then use those measures to test for the impact of trade policy uncertainty on investment and find that, in 2017 and 2018, the rise in trade policy uncertainty predicts a decline in aggregate investment of between 1 and 2 percent. This internal Fed research study has contributed to the Fed’s heightened concerns about trade policy uncertainties.

Consistent with these empirical findings, U.S. real exports, which had grown at a 4 percent average annual rate in the two years ending in the second quarter of 2018, have fallen 1.7 percent in the last year. Industrial production, following a sizable increase in 2017 and early 2018, flattened and has fallen 1.0 percent since late 2018. Business fixed investment growth has slowed dramatically, from a 5.6 percent pace in the two years ending in the second quarter of 2018 to 2.6 percent in the last year—and it fell in the second quarter of 2019, and recent declines in durable goods shipments point to another decline in the third quarter. Other factors may be at play, but the negative impacts of the tariffs and related uncertainties on exports, industrial production, business investment, and confidence have offset the positive impulses of the Trump administration’s deregulatory and tax reform initiatives.

Global trade volumes have declined 1.25 percent year-over-year, a marked reversal from their strong gains that averaged over 4 percent annually before tariffs were ramped up in mid-2018. Global industrial production has declined 0.7 percent in advanced economies, with pronounced impacts among China’s largest trading partners that rely on manufacturing exports. Excluding construction, industrial production is down 2.0 percent year-over-year in Japan, 22.8 percent in South Korea, and 24.9 percent in Germany. This has resulted in declining productivity, which has begun to spill into labor markets and domestic economic activity. China’s growth has clearly softened, and various measures suggest that its official data overstate actual economic performance. Along with the natural deceleration of China’s potential growth, the U.S. tariffs have adversely affected its high-powered export-related manufacturing sector. In the year ending September 2019, exports have fallen 0.6 percent while imports have declined 6.5 percent, compared to their annualized increases of 9.1 percent and 16 percent, respectively, in 2017–18. Industrial production has slowed to 4.4 percent year-over-year, its slowest since early 2009 during the financial crisis and deep global recession.

The longer the tariffs are in place and policy uncertainties persist, the larger the cumulative economic impacts will be (Handley and Limão 2017). Suppressing business investment reduces the stock of capital while disruptions to highly interconnected global supply chains and international flows of human capital constrain aggregate supply and productive capacity.

The Trump administration’s goals for China extend well beyond opening up China’s markets and include preventing China’s unfair treatment of intellectual property, investment practices that violate standard global practices, and cybersecurity violations. Accomplishing these goals would provide significant longer-run benefits. So would shaking up and reforming official channels that are used to resolve illegal practices like the WTO. But relying exclusively on escalating tariffs and threats of higher trade barriers as levers to achieve these objectives is imposing mounting costs on economic performance.

Tariffs and Monetary Policy

Tariffs and trade policy uncertainties add several dimensions of difficulty to the conduct of monetary policy and put the Fed in a bind. The Fed has achieved its dual mandate, with inflation slightly below the Fed’s 2 percent target, strong labor markets, and the unemployment rate at a 50-year low. Where does trade policy fit into the mix? The Fed’s discretionary approach to conducting monetary policy has led it to place a larger weight on the uncertainties of trade policy—both speculating what the policies may be and their economic effects—than on actual economic data. More fundamentally, while the tariffs and related uncertainties have dampened aggregate demand, they are imposing supply constraints on productive capacity that are beyond the scope of monetary policy to address.

Chairman Powell has made it clear that the Fed places a very high priority on avoiding a recession, so that as long as inflation remains below 2 percent, the Fed will tilt monetary policy against downside risks. The heightened policy uncertainties have led the Fed to put more weight on downside risks around its economic forecasts and temporarily abandon its “data dependent” conduct of monetary policy. It cut rates three times—in July, September, and October—even though the actual data clearly indicated that the economy was growing in line with the Fed’s forecast (and along its estimate of potential growth) while the Fed characterized labor markets as being strong. Powell emphasized these uncertainties at his Jackson Hole speech in August (Powell 2019): “In principle, anything that affects the outlook for employment and inflation could also affect the appropriate stance of monetary policy, and that could include uncertainty about trade. There are, however, no recent precedents to guide any policy response to the current situation.… Trade policy uncertainty seems to be playing a role in the global slowdown and in weak manufacturing and capital spending in the United States.”

Basing monetary policy on speculation about President Trump’s complex negotiating positions and their outcomes and hunches on risk probabilities moves the Fed’s discretion beyond data-dependence in a way that is inconsistent with its historical response to nonmonetary policy changes. Traditionally, the Fed has adjusted monetary policy in response to actual economic conditions following the enactment of fiscal policy legislation. That approach is different than changing monetary policy in anticipation of policies that may change and how the Fed perceives the economy will be affected. For example, in 2017, the Fed purposely stated that it would not adjust monetary policy to anticipated changes in fiscal policy but would respond to how any legislation may affect the economy.

The Fed’s current assessment that risks are to the downside—that is, acting now to avoid a recession later, may end up being correct or incorrect. Nevertheless, such an approach to policymaking moves the Fed further from any kind of systematic, rule-like behavior and toward discretion and guessing, which increases the probability of policy error that may undercut the Fed’s credibility and independence.

A more fundamental challenge facing the Fed is that monetary policy influences aggregate demand and is incapable of addressing supply constraints that are adversely affecting productive capacity. Like taxes, tariffs clearly reduce aggregate demand in the United States and globally. They raise prices, whose burdens are shared by global businesses, workers, and consumers—and they distort production and consumer behavior, generating deadweight losses. Global supply chains are also disrupted, which increases production costs and reduces economic efficiencies. Supply chains take time—in many cases, years—to adjust. Businesses cut back their expansion plans and decrease investment spending, which lowers GDP. Lower business investment reduces the capital stock, which weighs on productivity and potential growth.

Interest rates and the real costs of capital are already very low, while trade policy uncertainties dominate the business environment. Hence, a modest Fed rate cut will not boost business confidence and generate faster capital spending. Rate cuts may lift housing and wealth, or push down the U.S. dollar, but they cannot offset the constraints that trade barriers and distortions to global supply chains impose on productive capacity or clear up trade policy uncertainties (Levy 2019). Persistent monetary ease in the face of supply constraints will not stimulate growth but will have negative consequences. If the monetary easing actually stimulates aggregate demand, it would generate higher inflation. If aggregate demand is not stimulated, the lower rates are not harmless: they generate misallocations of resources, excess reliance on debt, and other distortions. They punish savers and benefit borrowers. By reducing the costs of debt service, low interest rates facilitate government deficit spending. And by lowering bond yields, they accentuate wealth inequality. Also, by giving the impression that monetary policy is ineffective, lower policy rates may undercut the Fed’s credibility.

Another nagging issue facing the Fed is President Trump’s public criticism of the Fed and his intertwining of the administration’s trade policies with China and Fed policy. Trump’s statements such as “who is our bigger enemy, Jay Powell or Chairman Xi?” (August 23, 2019) have led some observers to believe that the administration’s trade policy tactics are being used as a lever to force the Fed to cut rates. However inappropriate President Trump’s behavior or inaccurate the interpretation, it puts the Fed in a bad position and serves to undermine the Fed’s credibility in the public’s eye.

These observations provide several suggestions. The Fed should be more systematic and guided by rules in its conduct of monetary policy, rely more on data dependence, and not succumb to basing policy on hunches about risks and uncertainties. This is particularly true under current circumstances with the economy growing at potential, labor markets strong, bond yields at historic lows, and the Fed’s policy rate already uncomfortably close to the zero-lower bound.

Second, the Fed must be cognizant of the proper scope of monetary policy and explicitly communicate that it is limited in its abilities. Specifically, the Fed must be careful to acknowledge the differences between supply and demand effects on the economy and explicitly communicate what monetary policy is capable of achieving and how supply constraints imposed by tariffs and uncertainties are beyond its scope. It must avoid communications that only add to monetary policy uncertainties that add unnecessary volatility to financial markets and harm economic performance.

Third, the Fed should take every step and opportunity to emphasize its independence in pursuing the dual mandate that was established by Congress. It should also emphasize its political neutrality and sidestep any political debate.

Former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Bill Dudley weighed in on this issue with a statement (Dudley 2019a) that required an explanatory follow-up that illustrated the bind the Fed is in, but Dudley really stumbled badly and his suggestions would wind up as jeopardizing the Fed’s credibility as an apolitical, nonpartisan policymaker. Dudley correctly viewed President Trump’s escalating tariff policies as harming the economy and his barbs at the Fed as encouraging the Fed to become politicized. But while Dudley later disavowed (Dudley 2019b) his original suggestion that the Fed should consider adjusting monetary policy to influence the upcoming presidential election, he still recommended that the Fed should play different political angles in its responses and communications to President Trump’s economic policies. Moreover, he presumed that monetary policy is capable of offsetting the supply constraints imposed by trade policies. Dudley also suggested that the Fed’s policies should hinge in part on how the Fed perceives they will affect future trade policy. These notions suggest that the Fed should pursue political tactics in order to remain nonpolitical, and they convey a misunderstanding of the proper role of the Fed and monetary policy (Thornton 2019). The best way for the Fed to maintain political neutrality and operational independence is to conduct monetary policy independently of political pressures and the way it perceives that its policies may affect other (nonmonetary) policies. Along with this should be a full understanding of the proper scope of monetary policy and its communication publicly. This involves standing up to President Trump and steering clear of any politics or partisan maneuvering.

The Big Risk: Ending the Second Era of Globalization

The Trump tariffs on China and other countries, the retaliation against the United States, and the increase in trade policy uncertainty has resonance for what happened to the global economy during the interwar period when the first great era of globalization collapsed and contributed to a plunge into autarky and depression.

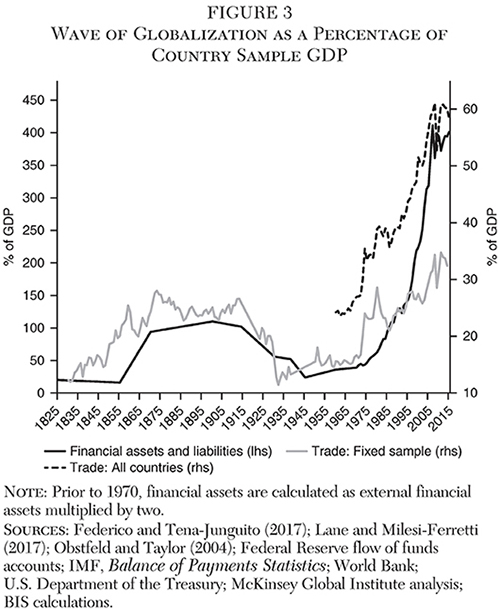

Although history never repeats, it often rhymes. Hence, understanding the lessons from the past can aid us in avoiding a recurrence of its serious policy errors. The world has experienced two eras of globalization in the past two centuries (Bordo 2017); see Figure 3. An understanding of what happened to end the first era of globalization is a very important cautionary tale for the considerable risks that the global economy faces from the current trade policies pursued by the Trump administration.

The first era of globalization, from the mid-19th century to August 1914, witnessed a massive transformation in international trade, financial globalization, and mass migration. The growth of trade relative to population and income began in earnest in the early 19th century, driven by technological change that vastly reduced the costs of shipping goods (the steamship and railroads) and political stability (the Treaty of Vienna and the Pax Britannica).

Empirical evidence for global trade integration comes in two dimensions: (1) the growth of trade relative to income, and (2) convergence in the prices of traded goods (Findlay and O’Rourke 2004). On both dimensions, although the process of international integration began with the opening up of the world with the Age of Discovery in the 16th century, the major thrust in globalization did not really occur until after the Napoleonic Wars.

The growth of trade from 1500 to 1800 averaged a little over 1 percent per year, far outpacing population growth of 0.25 percent. Between 1815 and 1914, trade measured by exports grew by 3.5 percent versus income growth of 2.7 percent. Commodity prices converged dramatically in the 19th century. For example, reflecting the sharp decline in transportation costs, the price of wheat in Liverpool relative to its price in Chicago that was 58 percent in 1815, fell to 16 percent in 1913. In addition to falling transport costs, globalization was spread by big reductions in tariff protection, beginning with Britain’s reduction of the corn tariffs after the Napoleonic Wars, culminating in their repeal in 1846. The movement toward free trade spread across Europe in a series of reciprocal agreements beginning with the Cobden Chevalier Treaty in 1860 between Great Britain and France. Within the next two decades, virtually all of Europe reduced tariffs—from 35 percent to 10–15 percent—in a series of bilateral agreements incorporating most favored nation clauses.

Financial market integration also burgeoned between 1870 and 1914. Many of the instruments of international finance, such as the bill of exchange, were invented in Italy in the Middle Ages and were perfected in Amsterdam in the 17th century (Goetzmann 2016). London succeeded Amsterdam as the key center of international finance by the 19th century. Obstfeld and Taylor (2004) portray the first era of financial globalization in the 19th century as centered in London but including the other advanced Western European countries as participants. Capital flowed from the mature economies of Western Europe that by then had gone through the Industrial Revolution and faced a reduced marginal productivity of capital (real rate of return) to the countries of new settlement that had abundant resources and higher real returns (Bordo 2002). The stock of global foreign assets relative to world GDP reached a peak of 20 percent in 1913 and was not surpassed again until late in the 20th century. The British held the lion’s share of overseas investments in 1914 at 57 percent, followed by France at 22 percent, Germany at 17 percent, and the Netherlands at 3 percent. These claims financed up to half of the capital stock of Argentina and 20 percent for Canada and Australia. Net capital outflows reached a peak of 9 percent of GDP for Great Britain just before World War I. For Canada, net capital inflows in the decade before the war were on a similar scale. The key factors that fostered the rapid development of global finance were technological change—the telegraph and the transatlantic cable, which was sucessfully laid between Britain and North America in 1866 starting a network still used today—and the classical gold standard with London as the center.

Adherence to gold convertibility by the major nations of the world ensured stable exchange rates and acted as a commitment mechanism or a “good housekeeping seal of approval” for countries seeking access to the London capital market (Bordo and Rockoff 1996).

Finally, like global commodity markets and capital flows, international migration surged in the 19th century and declined after World War I. The waves of migration in the later 19th century were driven largely by economic factors (e.g., the lure of higher real wages in the Americas and the supply-enhancing reduced transportation costs).

All of this came to an end with World War I and, subsequently, the Great Depression, but many of the seeds of its own destruction were planted earlier. In turn, globalization may have contributed to the wave of nationalism that led to World War I. The consequences of trade and factor mobility in the Golden Age were the convergence of real wages and per capita incomes between the core countries of Western Europe and much of the periphery. This outcome reflected the operation of classical trade theory (Williamson 1996).

These forces had important effects on the distribution of income. The massive migrations in the 1870 to 1914 period reduced the returns to landowners in the land-scarce, labor-abundant countries of Europe. At the same time, immigration threatened to worsen the income distribution for unskilled workers in countries of recent settlement, as immigrants competed with established workers for jobs in certain sectors. A political backlash ensued in each region. In Europe, landowners in France and Germany successfully lobbied for increased tariff protection of agriculture in the last two decades of the 19th century (O’Rourke and Williamson 1999; James 2001).

By the end of the century, the era of mass migration gave way to a wave of restrictions on the movement of people. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, passed by the U.S. Congress, was the culmination of decades of social and political lobbying against immigrants. At the end of 1901, Australia, with a much shorter history of immigration than the United States, passed its own Immigration Restriction Act aimed at stopping nonwhite immigration. Other countries introduced their own similar restrictions after 1919, and by the early 1920s, free migration ceased. The political and social limits to globalization through migration had therefore already been reached in the decades before 1914.

Financial globalization also led to a backlash but much later in the interwar period. Open capital accounts were associated with private investment booms and busts leading to financial crises (both currency and banking crises). Capital flowed from the capital-rich mature countries of Western Europe to the capital-scarce peripheral countries. But many countries lacked the institutional development to fully convert the new funds into productive investments and the funds-fueled asset-price booms (Bordo and Meissner 2017). Currency crises and banking panics often would lead to severe economic distress and sovereign debt crises.

Moreover, the classical gold standard that underpinned the first era of globalization was under attack. Under the gold standard, the world price level incurred long swings of deflation and inflation reflecting the growth of the real economy relative to the glacially slow growth of the world gold stock. Gold shortages (deflation) would ultimately stimulate technical innovation in gold mining and new discoveries (Bordo 1981; Rockoff 1984). But the timing of these events was adventitious (Keynes 1925). In the United States and elsewhere, the Great Deflation of 1873 to 1896 led to a populist outcry against gold and in favor of free silver and bimetallism (Eichengreen 2018).

The eruption of World War I in 1914 marked the end of the first era of globalization. Virtually all countries left the gold standard de jure or de facto once Britain suspended convertibility of sterling into gold after the financial crisis in 1914 (Roberts 2013). Both exchange controls and capital controls were widely imposed (Eichengreen 1992). World War I disrupted trade with tariffs and quotas.

Following the war, the movement toward protectionism increased. The United States was the worst offender with the Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act of 1922 and then the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930. Other countries retaliated: Great Britain, for example, used Imperial Preference, established with the Ottawa agreement of 1932, to discriminate against the United States. The Great Depression led to increasing tariffs intended to stimulate recovery. By the eve of World War II, multilateral trade collapsed into a system of bilateral trade and quotas. Finally, capital flows virtually ceased in the early 1930s following widespread sovereign debt defaults and the imposition of controls.

The situation today has some similarities to the interwar period but some key differences. Tariffs were increased markedly in both episodes, but so far today, the magnitude and scope of the imposed tariffs are dramatically less than in the 1930s. Also, while migration is being restricted, the scale and magnitude of the restrictions are a small fraction of those in the 1930s.

The differences are considerable:

- So far, the widespread imposition of capital controls that occurred in the interwar has not occurred.

- The structure of the world economy has changed. The advanced economies, which by the interwar period had already shifted from primary production (agriculture) to manufacturing, have now become much more dependent on services. The economies of many of the emerging countries (e.g., China and East Asia) have grown and matured to where the advanced countries were in earlier decades. This suggests that tariffs on manufacturing will have more of an impact on the emerging countries.

- There also has been greater integration in the production process across the globe. The most important development has been the global supply chain, which developed slowly in the 1980s between the advanced countries of North America, Europe, and Japan on the one hand and China and other emerging Asian economies on the other (Baldwin 2016). The development of just-in-time production techniques led to the formation of completely integrated global enterprises that combined advanced countries know-how with emerging markets lower cost labor (e.g., Walmart). There is evidence that the Trump tariffs have disrupted these processes. However, the global supply chain had already run into diseconomies of scale, which has led many multinational corporations to localize their production (Economist 2019).

Despite these considerable differences between present and historic conditions, there still is a risk that the rise in tariffs and other barriers and increased trade policy uncertainty may lead to a recessionary chain of events.

Fortunately, so far the effects of the U.S. tariffs and the retaliation are far less than what occurred in the 1930s. Research on Smoot-Hawley suggests that those onerous tariffs were not the primary cause of the Great Depression, but rather a serious exacerbating force (Irwin 2019). Crucini and Kahn (1996, 2003) show that based on a DSGE model, the Smoot-Hawley tariffs and the retaliation that followed created a recession that would be comparable to the garden variety recessions of the post-WWII era, with real GDP falling by about 2 percent. Moreover, their research finds that accounting for the impact of the tariffs on intermediate goods in the supply chain accounted for most of the drop in output. Today’s much more integrated and developed supply chains (with China as the linchpin) increase the potential economic costs of a trade war. Indeed, cutting China out of the supply chain, which President Trump recently urged in a tweet, could accentuate the negative impact. The process of substituting production away from China to other emerging countries would eventually alleviate the problem, but such adjustments are very costly and take considerable time. It is important to remember that it took several decades of learning-by-doing for China to have become so tightly integrated with the United States and Europe, and it will be very costly for the other emerging market economies to replicate this.

On the other hand, policymakers today have a far deeper understanding of how to stabilize the economy (even when interest rates hit the zero-lower bound) with a broader array of policy tools that did not exist 80 years ago. The presence of monetary and fiscal policy tools, automatic stabilizers, and international monetary and fiscal policy coordination, as well as the heightened sophistication of financial markets and capital flows, greatly reduces the likelihood of a 1930s-type disaster.

The risk remains, however, that further increases in trade protection and barriers that slow the flows of migration will reverse the economic advances of the second era of globalization (which accelerated following the collapse of Bretton Woods in the 1970s). This would greatly harm U.S. economic performance and lower long-run growth prospects. In present-value terms, this would translate into significant losses in standards of living and well-being. This scenario would be a tragedy because it would have been caused by preventable policy errors.

References

Ahir, H.; Bloom, N.; and Furceri, D. (2019) “Caution: Trade Uncertainty Is Rising and Can Harm the Global Economy.” VOX CEPR Policy Portal (July 4).

Amiti, M.; Redding, S.; and Weinstein, D. (2019) “The Impact of the 2018 Trade War on U.S. Prices and Welfare.” NBER Working Paper No. 25672 (March).

Baker, S.; Bloom, N.; and Davis, S. (2016) “Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 131 (4): 1593–636.

Baldwin, R. (2016) The Great Convergence. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Bordo, M. D. (1981) “The Classical Gold Standard: Some Lessons for Today.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 63 (May): 2–17.

_________ (2002) “The Globalization of Financial Markets: What Can History Teach Us?” In L. Auernheimer (ed.), International Financial Markets, 29–78. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

_________ (2017) “The Second Era of Globalization Is Not Yet Over: An Historical Perspective.” NBER Working Paper No. 23786 (September).

Bordo, M. D, and Meissner, C. M. (2017) “ Growing Up to Stability? Financial Globalization, Financial Development and Crises.” In P. L. Rousseau and P. Wachtel (eds.), Financial Systems and Economic Growth: Credit Crises and Regulation from the 19th Century to the Present, 14–51. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bordo, M. D., and Rockoff, H. (1996) “The Gold Standard As a ‘Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval.’” Journal of Economic History 56 (2): 389–428.

Bown, C., and Irwin, D. (2019) “Trump’s Assault on the Global Trading System.” Foreign Affairs (September/October).

Caldara, D.; Iacoviello, M.; Molligo, P.; Prestipino, A.; and Raffo, A. (2019) “The Economic Effects of Trade Policy Uncertainty.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (August).

Chudik, A. (2019) “President Trump’s Tariff Spree.” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas (June 7).

Crucini, M. J., and Kahn, J. A. (1996) “Tariffs and Economic Activity: Lessons from the Great Depression.” Journal of Monetary Economics 38: 427–67.

_________ (2003) “Tariffs and the Great Depression Revisited.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Staff Reports No. 172.

Dudley, B. (2019a) “The Fed Shouldn’t Encourage Trump’s Trade War.” Bloomberg Opinion (August 27).

_________ (2019b) “What I Meant When I Said ‘Don’t Enable Trump.” Bloomberg Opinion (September 4).

Ebeke, C., and Siminitz, J. (2018) “Trade Uncertainty and Investment in the Euro Area.” IMF Working Paper WP/18/281 (December).

The Economist (2019) “Special Report: Global Supply Chains” (July 11).

Eichengreen, B. (1992) Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and The Great Depression, 1919–1939. New York: Oxford University Press.

_________ (2018) The Populist Temptation: Economic Grievance and Political Reaction in the Modern Era. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fajgelbaum, P.; Goldberg, P.; Kennedy, P.; and Khandelwal, A. (2019) “The Return to Protectionism.” NBER Working Paper No. 25638 (March).

Federico, G., and Tena-Junquito, A. (2019) “World Trade, 1800–1938: A New Synthesis.” Revista de Historia Economica 37 (1): 9–41.

Findlay, R., and O’Rourke, K. (2004) “Commodity Market Integration, 1500–2000.” In M. D. Bordo, A. Taylor, and J. G. Williamson (eds.), Globalization in Historical Perspective, 13–64. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Goetzmann, W. (2016) Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Handley, K., and Limão, N. (2017) “Policy Uncertainty, Trade, and Welfare: Theory and Evidence for China and the United States.” American Economic Review 107 (9): 2731–83.

Irwin D. (2019) “U.S. Trade Policy in Historical Perspective.” NBER Working Paper No. 26256 (September).

James, H. ( 2001) The End of Globalization: Lessons from the Great Depression. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Keynes, J. M. (1925) The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill. London: Macmillan.

Lane, P. R., and Milesi-Ferreti, G. M. (2017) “International Financial Integration in the Aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis.” IMF Working Paper WP/17/115 (May).

Levy, M. (2019) “Monetary Policy Realities Facing the ECB, Fed and BoJ: More Easing Won’t Stimulate Economies.” Center for Financial Stability (July 12).

Obstfeld, M., and Taylor, A. (2004) Global Capital Markets: Integration, Crisis and Growth. Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press.

O’Rourke, K., and Williamson, J. G. (1999) Globalization and History: The Evolution of a Nineteenth Century Atlantic Economy. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Powell, J. (2019) “Challenges for Monetary Policy.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Jackson Hole Symposium (August).

Roberts, R. (2013) Saving the City: The Great Financial Crisis of 1941. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rockoff, H. (1984) “Some Evidence on the Real Price of Gold, Its Cost of Production and Commodity Prices.” In M. D. Bordo. and A. J. Schwartz (eds.), A Retrospective on the Classical Gold Standard: 1821 to 1931, 613–44. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Thornton, D. L. (2019) “Protecting the Fed’s Independence Dudley’s Way.” Common Sense Economics Perspective, No. 11 (September 8).

Varas, J. (2019) “The Total Cost of Trump’s Tariffs.” American Action Forum (October 25).

Williamson, J. G. (1996) “Globalization, Convergence and History.” Journal of Economic History 56: 277–306.

About the Authors

Michael D. Bordo is Distinguished Professor at Rutgers University and Distinguished Visiting Scholar at the Hoover Institution. Mickey D. Levy is Chief Economist for the Americas and Asia at Berenberg Capital Markets. Both are members of the Shadow Open Market Committee (SOMC). The authors thank Andrew Filardo, Owen Humpage, Bernie Munk, and George Shultz for helpful comments. An earlier version of this article was presented at the SOMC’s September 27, 2019, meeting.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.