Thanks to President’s Trump’s picks for prospective Fed Board nominees, the subject of gold price targeting (or a gold “price rule”) is getting attention once again. The idea, which got a lot of attention back in the 1980s, after Arthur Laffer and other supply-siders, including Alan Reynolds, first began promoting it, is that the Fed could mimic a gold standard, keeping inflation in check and otherwise making the dollar “sound,” by employing open-market operations to stabilize the price of gold.1 The topic has come up again because three of Trump’s prospective nominees have at one time or another suggested that the United States should revive the gold standard, and two of them, Herman Cain and Stephen Moore, are full-fledged supply-siders (see Benko 2019). Although Cain and Moore are no longer in the running, Judy Shelton, the third gold standard fan, is still in the race, along with Chris Waller of the St. Louis Fed (see Matthews and Torres 2019). Shelton also has strong supply-side leanings.

Thanks to President’s Trump’s picks for prospective Fed Board nominees, the subject of gold price targeting (or a gold “price rule”) is getting attention once again. The idea, which got a lot of attention back in the 1980s, after Arthur Laffer and other supply-siders, including Alan Reynolds, first began promoting it, is that the Fed could mimic a gold standard, keeping inflation in check and otherwise making the dollar “sound,” by employing open-market operations to stabilize the price of gold.1 The topic has come up again because three of Trump’s prospective nominees have at one time or another suggested that the United States should revive the gold standard, and two of them, Herman Cain and Stephen Moore, are full-fledged supply-siders (see Benko 2019). Although Cain and Moore are no longer in the running, Judy Shelton, the third gold standard fan, is still in the race, along with Chris Waller of the St. Louis Fed (see Matthews and Torres 2019). Shelton also has strong supply-side leanings.

These facts prompted Representative Jennifer Wexton (D‑Va.) to ask Jerome Powell, following his July 10, 2019, testimony, whether the United States should “go back to the gold standard.” In response, Powell, whether because he had a Laffer-style gold price rule in mind or for some other reason, interpreted the question as one asking whether the Fed should “stabilize the dollar price of gold.” That, he said, wouldn’t be a good idea:

There have been plenty of times in fairly recent history where the price of gold has sent signals that would be quite negative for either [maximum employment or stable prices].… If you assigned us [to] stabilize the dollar price of gold, monetary policy could do that, but the other things would fluctuate, and we wouldn’t care. We wouldn’t care if unemployment went up or down. That wouldn’t be our job anymore [Powell 2019].

Powell’s statement raises three questions. One is whether it’s proper to equate reviving the gold standard with having the Fed target the price of gold, as Powell did. The second is whether Judy Shelton has herself endorsed a gold price rule. The third is whether such a rule would be as disastrous as Powell claims. This article is devoted to answering, or trying to answer, these questions.

A Gold Target Is Not a Gold Standard

Answering the first question is relatively easy. So far as most fans of the gold standard are concerned, and despite what Jay Powell suggested, reviving the gold standard and having the Fed target the price of gold aren’t the same thing. In what many consider to be a genuine gold standard, paper money consists of readily redeemable claims to gold; and it’s that redeemability—and not any central bank “targeting”—that keeps that paper on a par with the gold it represents (see White 2019).

At a still more fundamental level, in a true gold standard, only gold itself is money proper, while paper money consists of legally binding IOUs, exchangeable for definite amounts of gold, not as a matter of policy, but as a matter of contract (Selgin 2015). Making the equivalence of paper money and gold a matter of binding contracts, enforceable in ordinary law courts, rather than one of pledges made as a matter of public policy, makes that equivalence especially credible (Selgin and White 2005). The sovereign immunity enjoyed by most modern central banks, in contrast, renders them unfit to operate genuine gold standards even when their notes are officially redeemable in gold, because they can always change their policy, dishonoring a prior redemption pledge, with impunity. Every older central bank has, in fact, done just that at some point in its history (see Redish 1993).

So although a central bank may target the price of gold, or adhere to a gold “price rule,” by doing so, it creates a “pseudo” rather than a “real” gold standard (see Salerno 1983). Having a real gold standard, in contrast, doesn’t call for having a central bank at all, as many past examples make clear (see Selgin 2019b). Indeed, so far as many fans of the classical gold standard (including this one) are concerned, central banks have mainly served to muck up the gold standard (see Selgin 2010).

Finally, it is by no means clear that the macroeconomic consequences of a gold price rule would be the same as those of a genuine gold standard, in part precisely because such a rule can be more easily set aside and would therefore lack the credibility of a genuine gold standard.

Some Gold Standard Proponents Still Favor a Gold Price Rule

Despite its possible shortcomings, gold price targeting has continued to have advocates since the 1980s. Jack Kemp pleaded its case again in a 2001 Wall Street Journal op-ed, and Steve Forbes has been carrying the gold price rule torch ever since. Referring to then-Representative Ted Poe’s (R‑Tenn) 2013 Federal Reserve Transparency Act, Forbes wrote:

Unlike in days of old we don’t need piles of the yellow metal for a new [gold] standard to operate. Under Poe’s plan—an approach I have long favored—the dollar would be fixed to gold at a specific price. For argument’s sake let’s say the peg is $1,300. If the price of gold were to go above that, the Federal Reserve would sell bonds from its portfolio, thereby removing dollars from the economy to maintain the $1,300 level. Conversely, if the gold price were to drop below $1,300, the Fed would “print” new money by buying bonds, thereby injecting cash into the banking system [Forbes 2013].

Nathan Lewis is another gold standard fan who considers a stable gold value for the dollar the essence of a gold standard, no matter how that stability is achieved (see Lewis 2018).

Former prospective Fed nominees Herman Cain and Stephen Moore both spoke and wrote of the benefits of having the Fed target the price of gold. Although he was better known for his notorious 9–9‑9 plan, Cain also had a plan for establishing a “21st Century Gold Standard.” According to Charles Kadlec (2012), that plan would have assigned the Fed a single target—the value of the dollar in terms of gold—and the tools to achieve that target. Open market operations would be used for the sole purpose of increasing or decreasing the supply of dollars in order to maintain the dollar/gold exchange rate. Other than setting the discount rate to fulfill its role as lender of last resort, the Fed would be prohibited from targeting or manipulating interest rates.

Although Steve Moore would rather have had the Fed target a broad index of commodity prices (see Selgin 2019a), according to a report in The New York Times, he agrees with Steve Forbes that having the Fed target the price of gold would be “a lot better than what we have now” (Tankersley 2019).

Judy Shelton Is Not One of Them

Powell was very careful, in answering representative Wexton’s question, to make clear that his remarks shouldn’t be taken as referring to the views of Judy Shelton or any other prospective Fed board nominee. That’s just as well, because although she certainly favors a gold standard of some sort, so far as I can determine, Shelton has never recommended gold price targeting.

It is true that in her book, Money Meltdown, Shelton (1994: 298–301) discusses the idea of having the Fed target the price of gold (which many thought it was then doing under Greenspan’s leadership), showing much sympathy for it. But she ultimately concludes, for several reasons, that the policy would be a poor alternative to a real gold standard founded upon actual convertibility of paper dollars into gold.

Taking the same subject up again more recently, in her pamphlet Fixing the Dollar, Shelton comes to the same conclusion, to wit: that despite the greater challenges involved, “the advantages of forging an inviolable link between the value of U.S. money and gold through fixed convertibility seem to make it well worth tackling the difficulties” (Shelton 2011).

Finally, as if to settle any doubts, in a CNBC interview in June 2019, Shelton declared,

I’m sure I’ve never said that the Fed should have a price rule to ratchet up or down interest rates in accordance with the daily price of gold. But I’m sure that if anything I would have said a price rule I don’t think is a good idea. I’ve never suggested that. I’m not badmouthing the gold standard. I’m saying look to see what you like about prior systems that have worked and see if we could develop a future system that would incorporate the virtues of things that worked in the past [Shelton 2019a].

Consequently, the drawbacks of gold price targeting, whatever they may be, cannot fairly be laid at Judy Shelton’s door, whether implicitly or explicitly (see Shelton 2019b). For while a gold price targeting regime may resemble a convertibility-based gold standard in one respect, it also differs greatly from it in others. Its flaws aren’t the flaws of the Bretton Woods system (see IMF and World Bank n.d.), just as the flaws of the Bretton Woods system aren’t those of the classical gold standard (see Koning 2015). Perhaps they are all faulty. Still, each deserves a separate hearing.

Is Powell Right? Some Econometric Results

So we come to the third question, which calls for giving proposals for targeting the price of gold a proper hearing. Although such proposals can be assessed in all sorts of ways, one popular approach involves asking how well things would have gone had the Fed actually targeted the price of gold in the past, and comparing the answer to how well things went in fact. While this approach has its drawbacks, it at least avoids the “nirvana fallacy,” which consists of pointing to how some alternative policy or regime falls short of some blackboard (or whiteboard) ideal, and rejecting it on that basis, instead of comparing it to an existing, also imperfect arrangement (see White 2012).

Economists usually use statistical techniques to try to answer “what if” questions. So I turned to my former University of Georgia colleague Bill Lastrapes, who worked on a similar project with me years ago. That project investigated claims to the effect that Greenspan’s Fed had actually been practicing gold price targeting. Although Lastrapes and I concluded that those claims contained rather more than a kernel of truth, we made no attempt to say whether the policy was or wasn‘t a good idea (Lastrapes and Selgin 1996).

There are all sorts of ways to go about such a counterfactual exercise, each with its drawbacks. One way is to rely on a simple reduced-form regression of the price of gold on the fed funds rate—the Fed’s immediate target—and then infer from it, first, where the fed funds target would have had to be set at any given time to maintain a fixed value of gold and, second, how inflation and output would have responded to that rate setting. Using this approach (or the first part of it) to assess Herman Cain’s gold price rule proposal, Menzie Chinn (2019) concluded that, had that policy been put into effect in January 2000, between then and March 2019, the Fed would have had to increase its fed funds target by 14.89 percentage points, whereas, in fact, it reduced it by 3.04 percentage points, to a level that President Trump, and many others besides, still consider too high.

While Chinn’s approach is certainly suggestive, it suffers in treating the fed funds rate itself as an “exogenous” variable, and thereby failing to allow for the simultaneous determination of the price of gold and interest rates. More generally, Chinn ignores general equilibrium effects. To take those effects into account, Lastrapes and I used a simple, structural VAR (vector auto regression) model. The model has four equations for as many variables: real GDP, the inflation rate, the fed funds rate, and the price of gold. In the “factual” regression we take to the data, we assume that the Fed sets the funds rate in response to changes in both GDP and the price level, but not in response to changes in the price of gold. In contrast, in the “counterfactual” regression, we let the Fed adjust the funds rate so as to either rigidly fix the nominal price of gold or stabilize it around a constant mean. In both cases, we rely on various other identifying restrictions to distinguish the Fed’s rule from the effect of non-Fed instigated interest rate changes on gold prices.

All that still leaves open plenty of options, so we considered several, based on data starting either in 1973 or in 1979. The results in every case, like those from Chinn’s simple regression, support Powell’s position. Indeed, they suggest that a gold price rule would be an even worse idea than Chinn’s findings imply.

To drive that point home, I’ll report here results from only one of the many regressions Lastrapes and I considered: the one that yielded results most favorable to a gold price rule. (The complete study is not yet ready for distribution.) That regression refers to the post-1979 sample period only. Going back to 1973 makes gold price targeting look worse. The regression also assumes, again in gold price targeting’s favor, that instead of trying to keep the price of gold absolutely constant, the Fed allows it to vary somewhat above and below its targeted value.

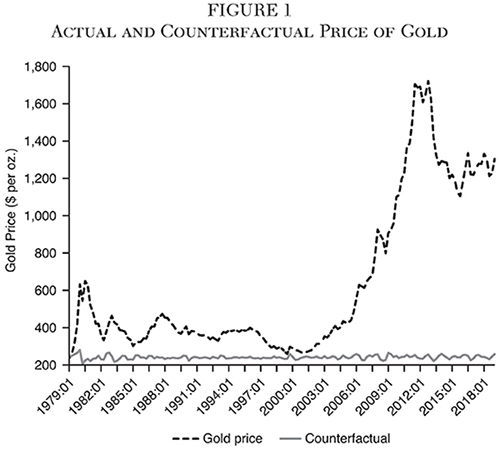

Looking first at the findings for the price of gold itself, Figure 1 compares gold’s actual price during the sample period to its counterfactual price, where the latter reflects our assumption that a gold-targeting Fed tolerates some fluctuations in that price.

/p>

/p>

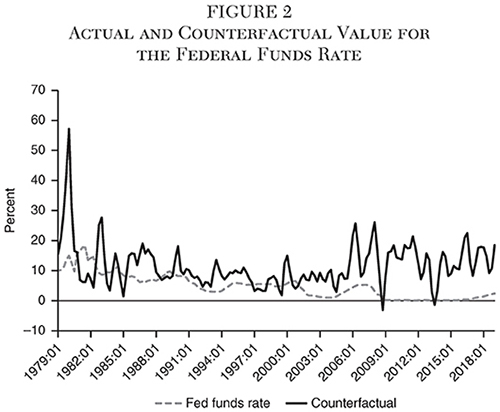

Evidently, even keeping gold’s price within these broadened limits requires substantial changes in the Fed’s monetary policy settings. Just how substantial can be seen in Figure 2, showing actual and counterfactual values for the federal funds rate, where the counterfactual values are those needed to generate the relatively stable price of gold shown in Figure 1. For the period since 2005, which includes the financial crisis and recession, the average counterfactual funds rate exceeds 10 percent; on some occasions it exceeds 20 percent.

These numbers are roughly in agreement with Chinn’s findings. But we can also see some consequences of gold price targeting not evident from Chinn’s simple regression, including the fact that it would have made the fed funds rate highly volatile. During the year 2000, for example, the rate would have had to vary by about 12 percentage points. Other years would have seen still larger movements. Had the Fed instead tried to keep the price of gold absolutely constant, the fed funds rate would have bounced around even more. The greater volatility makes intuitive sense, because under a gold price target, the Fed must respond to fluctuations not only in the absolute but in the relative price of gold.2

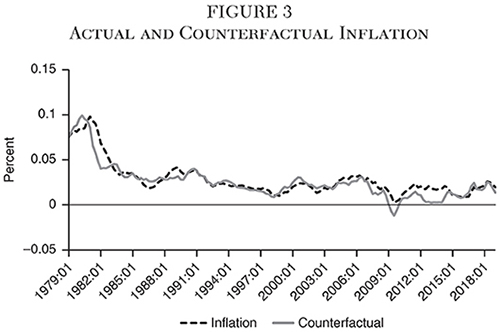

Moving next to inflation, although gold price targeting would have meant more rapid disinflation at the start of the Volcker era, for most of the Great Moderation, it would have made relatively little difference (perhaps in part because Greenspan’s Fed was then using gold as an indicator), resulting in slightly less inflation in some periods, and slightly more in others. Only starting in the mid-2000s does the alternative policy begin to make a big difference again, by yielding (until 2015 or so) persistently lower inflation (Figure 3). But that lower inflation includes severe deflation during much of 2009, which hardly makes the counterfactual inviting, especially when one takes account of corresponding effects on output.

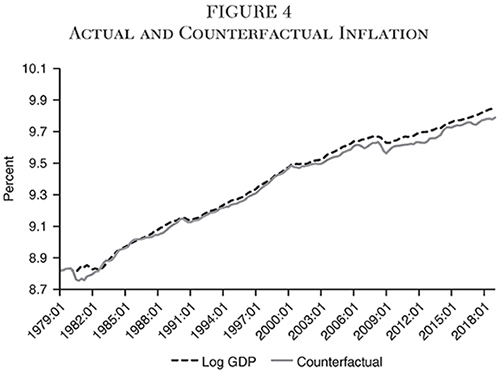

Finally, Figure 4 shows those output effects and more. Counterfactual real GDP runs persistently below actual real GDP from 2000 onward, with a particularly severe dip—that is, relative to the already severe actual dip—during 2008-09, and a substantially lower level from late 2009 onward. Under gold price targeting, in short, the Great Recession would have been more like a second Great Depression. Indeed, since the original Great Depression actually consisted of two separate downturns, it might have qualified as America’s Greatest Depression.

Some Caveats

While econometric findings similar to those I’ve reported no doubt informed Powell’s answer to Representative Wexler, such findings need to be taken with a grain of salt. For while they yield more information than Chinn’s simple regression, they may still be unreliable. In particular, they may still run afoul of the famous “Lucas Critique.”

That critique, as originally summed up by Robert Lucas himself, holds that, because “the structure of an econometric model consists of optimal decision rules of economic agents, and … optimal decision rules vary systematically with changes in the structure of series relevant to the decision maker … any change in policy will systematically alter the structure of econometric models” (Lucas 1976: 41). As Thomas Sargent later explained, VARs are particularly ill-suited for evaluating “the effect of … changes in the feedback rule governing a monetary or fiscal policy variable [because] when one equation … describing a policy authority’s feedback rule changes, in general, all of the remaining equations will also change.” This means, among other things, that the uses to which VARs can safely be put are “more limited than the range of uses that would be possessed by a truly structural simultaneous equations model” (Sargent 1979: 13–14).

Of particular concern to both Lucas and Sargent are instances in which agents’ expectations of the policy process are likely to change when policymakers change their own behavior (see Rudebusch 2002). As Christopher Sims puts it, “evaluating changes in policy rule as if they could be made permanently, while leaving expectations formation dynamics unchanged, is a mistake” (Sims 1998).

That concern is clearly relevant in the present instance. Consider our VAR model’s gold price equation, the coefficients of which are functions of the supply of and demand for gold. Our counterfactual assumes that those coefficients stay the same whether or not the Fed targets the price of gold. But that assumption is suspect. Gold is, after all, demanded in part as an inflation hedge (Ghosh et al. 2004). Consequently, by credibly switching to a gold price rule, the Fed might reduce that demand by dampening fears of inflation. Put another way, the shocks in our gold price equation could be smoothed under gold price targeting. Because it doesn’t allow for this, our counterfactual exercise may overstate the shortcomings of a gold price rule, especially by exaggerating the fed funds rate changes needed to implement it.

If, on the other hand, the Fed’s gold price rule is less than fully credible, our findings might still be misleading, because that less-than-credible rule could itself give rise to a speculative demand for gold based on fears that the rule will change. In that case, the Fed’s (unconvincing) switch to a gold price rule could end up making the fed funds rate more rather than less volatile than if it did not pretend to target gold at all.

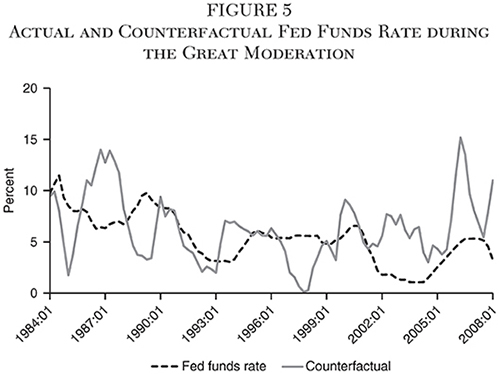

Were our sample period one during which changing fears of inflation were not an important source of innovations to the demand for gold, our counterfactual estimates would be less vulnerable to the Lucas Critique. With this understanding in mind, Bill repeated our counterfactual analysis for the Great Moderation (1984–2008) sub-period, during which inflation fears are generally understood to have been quieted. Although the counterfactual fed funds rate for this period, shown in Figure 5, is somewhat less volatile, it still swings dramatically, while the other counterfactual series show results similar to those from the longer sample period.

Conclusion

The findings reported here suggest that, though our results are subject to the Lucas Critique, they may not be all that misleading. Thus we might echo Sims’s claim, made with regard to counterfactual work of his own, that the possibilities raised by Lucas are “reasons to be somewhat cautious about these results, not a reason for ignoring them” (Sims 1998: 156). Indeed, these findings are consistent with the hypothesis that while Greenspan’s Fed may have treated the price of gold as a policy indicator, as my and Lastrapes’s earlier research suggests, had the Fed gone further by trying to limit gold’s price within still-narrower bounds, it would have had to tolerate much more dramatic swings in its fed funds target.

But Sims’s thinking mustn’t be stretched too far. However useful our counterfactual exercise may be for assessing the likely consequences of gold price targeting, that exercise is far less capable of telling us what consequences might result from a return to a more genuine gold standard, including a Bretton-Woods type arrangement of the sort Judy Shelton has sometimes recommended (see, e.g., Shelton 2018). For that more radical regime change would almost certainly involve still more far-reaching changes in the coefficients of our models’ equations, making any results it might yield especially dubious. That doesn’t mean, of course, that reviving Bretton Woods, or establishing any other sort of “genuine” gold standard, would be a good idea (see Steil 2014). It is just that, whether it is or isn’t, is not something one can hope to decide, even very tentatively, just by running a few regressions.

References

Benko, R. (2019) “Stephen Moore and Herman Cain Are Just What the Fed Needs.” The American Spectator (April 17).

Chinn, M. (2019) “What Would It Take to Implement Cain’s Gold Standard, Interest-Rate-Wise?” Econbrowser (April 7).

Cochrane, J. H. (2019) “Forget the Gold Standard and Make the Dollar Stable Again.” Wall Street Journal (July 17).

Forbes, S. (2013) “Advance Look: What the New Gold Standard Will Look Like.” Forbes (May 27).

Ghosh, D.; Levin, E.; Macmillan, P.; and Wright, R. (2004) “Gold as an Inflation Hedge.” Studies in Economics and Finance 22 (1): 1–25.

International Monetary Fund and World Bank (n.d.) “The Flaws of the IMF Bretton Woods System.” Available at www.americanforeignrelations.com/E‑N/International-Monetary-Fund-and-World-Bank-The-flaws-of-the-imf-bretton-woods-system.html#ixzz64ujdIOBU.

Kadlec, C. (2012) “Herman Cain’s Path to a 21st Century Gold Standard.” Forbes.com (May 21).

Kemp, J. (2001) “Our Economy Needs a Golden Anchor.” Wall Street Journal (June 28).

Koning, J. P. (2015) “Was Bretton Woods a Real Gold Standard?” Moneyness (December 24).

Laffer, A. B. (1980) “Reinstatement of the Dollar: The Blueprint.” Rolling Hill Estates, Calif.: A. B. Laffer Associates.

Laffer, A. B., and Kadlec, C. W. (1982) “The Point of Linking the Dollar to Gold.” Wall Street Journal (October 13): 32.

Lastrapes, W. D., and Selgin, G. (1996) “The Price of Gold and Monetary Policy.” Working Paper, Department of Economics, University of Georgia (September).

Lewis, N. (2018) “Did We Just Enjoy the ‘Yellen Gold Standard’?” Forbes.com (April 2).

Lucas, R. E. Jr. (1976) “Econometric Policy Evaluation: A Critique.” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 1: 19–46.

Matthews, S., and Torres, C. (2019) “St. Louis Fed’s Waller Joins Bullard in a Dovish Duo at the Fed.” Bloomberg (July 3).

Powell, J. (2019) Q&A following Chairman Powell’s Testimony before the Committee on Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives. CNBC (July 10). Available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=2tnvNfCWGsw.

Redish, A. (1993) “Anchors Aweigh: The Transition from Commodity Money to Fiat Money in Western Economies.” Canadian Journal of Economics 26 (4): 777–95.

Reynolds, A. (1983) Why Gold? Cato Journal 3 (1): 211–38.

Rudebusch, G. D. (2002) “Assessing the Lucas Critique in Monetary Policy Models.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Working Paper No. 2002-02.

Salerno, J. T. 1982) “The Gold Standard: An Analysis of Some Recent Proposals.” Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 16 (September 9).

_________ (1983) “Gold Standards: True and False.” Cato Journal 3 (1): 239–75.

Sargent, T. J. (1979) “Estimating Vector Autoregressions Using Methods Not Based on Explicit Economic Theories.” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 3 (3): 8–15.

Selgin, G. (2010) “Central Banks as Sources of Financial Instability.” The Independent Review 14 (4): 485–96.

_________ (2015) “Law, Legislation, and the Gold Standard.” Cato Journal 35 (2): 251–72.

_________ (2019a) “More on Commodity Price Targeting.” Alt‑M (April 9).

_________ (2019b) “Is There Such a Thing as a Free-Market Gold Standard?” Alt‑M (July 9).

Selgin, G., and White, L. H. (2005) “Credible Currency: A Constitutional Perspective.” Constitutional Political Economy 16: 71–83.

Shelton, J. (1994) Money Meltdown: Restoring Order to the Global Currency System. New York: The Free Press.

_________ (2011) Fixing the Dollar Now: Why U.S. Money Lost Its Integrity and How We Can Restore It. Washington: Atlas Economic Research Foundation.

_________ (2018) “The Case for a New International Monetary System.” Cato Journal 38 (2): 379–89.

_________ (2019a) Interview with CNBC Commentator Gina Heeb (June 6).

_________ (2019b) “Protecting the Federal Reserve.” Interview with Money & Banking. Available at www.moneyandbanking.com/commentary/2019/7/6/protecting-the-federal-reserve (July 8).

Sims, C. A. (1998) “The Role of Interest Rate Policy in the Generation and Propagation of Business Cycles: What Has Changed since the ’30s?” In Proceedings of the 1998 Annual Research Conference, 121–67. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Steil, B. (2014) “The Myth of Bretton Woods.” Wall Street Journal (July 28).

Tankersley, J. (2019) “Trump Taps Fed Critic Stephen Moore for Board Seat.” New York Times (March 22).

White, L. H. (2012) “Recent Arguments against the Gold Standard.” Free Market Forum.

_________ (2019) “A Gold Standard Does Not Require Interest-Rate Targeting.” Alt‑M (April 18).

1 See Laffer (1980), Laffer and Kadlec (1982), and Reynolds (1983). Salerno (1982) provides an analysis of supply-siders’ proposals for a gold price rule.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.