Central bank independence (CBI) became a globally accepted truth of economics about 30 years ago. It is clearly valuable for ensuring that monetary policy is conducted in a way that is consistent with appropriate central bank objectives and free of political influences. Nevertheless, CBI has been under attack in both the developed world (President Trump is a frequent critic) and in emerging markets (e.g., in Turkey and India). Thus, the time is ripe to take a new look at CBI. An examination of its origins will provide a framework for examining its current status.

In this article, we examine how central bank independence became the cornerstone of central banking in the late 20th century and how the idea has been challenged by recent events. We find that in the developed world, the strong emphasis on CBI led to a narrow view of the role of central banks. As a result, central banks were unaware of financial stability risks and ill prepared to respond to the financial crisis. In the less-developed, emerging market world, CBI improved policy management and governance.

The arguments regarding CBI are focused on the monetary policy role of central banks that emerged in the post-World War II era as economists began to understand the importance of interest rates and credit aggregates to the macroeconomy. Historically, central banks, including some that were private-sector entities, were explicitly agents to carry out government policy (Parkin and Bade 1978). This would be true of the Bank of Japan and the Netherlands’ Bank among others. Other central banks, including the Swiss National Bank and the Bank of England, did not establish their statutory independence until recently.

The traditional view of central bank functions is associated with Walter Bagehot, the 19th-century British journalist who articulated the idea that a central bank should act as the lender of last resort to the financial system. By providing liquidity, the central bank can prevent crises and preserve stability. For example, the Fed was established as a lender, to use discounting to maintain financial stability (“furnish an elastic currency” in the words of the legislation). The lending functions of the Federal Reserve and other central banks diminished in importance through the latter half of the 20th century as macro monetary policy became the focus and new policy tools were developed. By the end of the 20th century, central banks were primarily associated with the macroeconomic policy role. However, the financial crisis of 2007-09 brought a renewed emphasis on the lender-of-last-resort function and the use of central bank lending to ensure financial stability.

While the overwhelming majority of academic and central bank practitioners continue to support central bank independence, it is clear that, while independence continues to be protected, its golden age ended with the crisis a decade ago, and it did not end gently. The first wave of charges against central banks was straightforward: the worst financial crisis since the 1930s took place after central bankers worldwide were handed, or thought they were handed, most of the economic-management levers and were given much discretion in the design and certainly the implementation of their economic policies. Given these perceptions, there is no way they can now avoid blame, and preserve intact their prestige and standing. Indeed, the reputation of “independent central bankers” was severely damaged by the crisis, removing partially the implicit taboo involved in asking the unmentionable: perhaps central banks should not be, nor should aim at being, so independent after all?

However, independence, at least formally, appears to be surviving. There was no lethal follow-up after the initial crisis-induced assaults. This restraint may have been the consequence of the fact that, one way or another, the crisis was controlled and central banks were instrumental in avoiding — with huge help from government and regulators — the complete collapse of the financial system. But the seeds of doubts about independence were planted and more questions and criticism continue to arise. Many claim that in the 2000s, central banks unwittingly fueled the credit expansion that resulted in the crisis. This bad press may eventually translate into the political arena, as voters are chasing those that are seen as responsible for the crash and the austerity policies that ensued.

Moreover, a crucial element in shielding central bankers from the popular wrath is also being questioned — namely, their success in achieving and maintaining price stability. The argument is that the central banks’ role in such success, although relevant, was overstated given the strong exogenous disinflationary consequences of technology and globalization. Even more serious is the near-consensus view that independent central banks spectacularly failed to achieve and preserve financial stability, just as crucial a mission as its macroeconomic companion.

Of course, nobody claims that a country where politicians can overrule the central bank to promote excessive credit expansion or to print too much of their own currency is a good place to invest. But the tendency of independent central banks to focus on price stability and ignore the regulatory/financial stability side is also seen as a dangerous formula.

In summary, recent crises left the impression that central banks paid no price for their collective failure and, in fact, that they emerged even more powerful than before. Moreover, populist sentiment has found that central banks are an attractive target to blame for any economic woes that might exist.

Worse still, independence is further endangered by the fact that the crisis pushed central banks into making choices with lasting distributional consequences. By making massive purchases of government bonds, quantitative easing has held both short- and long-term interest rates low for a very long time. While this may have helped to stimulate declining economies, it has done so by making rich owners of financial assets richer still. At the same time, poorer savers relying on bank deposits have been getting next to nothing.

Recent developments could be a watershed in the public approach to central banks, particularly in countries where the sensitivity to income distribution changes is high. The public may not tolerate leaving decisions with important distributional and fiscal consequences (such as those related to bank resolutions) to unelected bodies.

Central bankers in both developed and emerging market countries are keenly aware that the circumstances that defined CBI and brought it into prominence have changed in the postcrisis world. The broadening role of central banks — to include a responsibility for financial stability — necessitates some review of central bank governance and the relationship between central banks and governments. Nevertheless, many central banks continue to claim that their mandate remains relatively narrow and that independence is crucial although they are agreeable to strengthening transparency and accountability.

We begin our reexamination of CBI with a discussion of its origins, starting with an important essay by Milton Friedman (1962). We then discuss why the idea caught on in the 1980s to become an uncontested element of the economics canon. We then turn to the role of CBI in the years leading up to and after the financial crisis. CBI has had some positive effects in emerging markets. However, in developed economies with an increased emphasis on financial stability, thinking about CBI needs to be modified. Finally, we examine a case study, the independence of the U.S. Federal Reserve in the postwar period. We find that CBI is often more an aspiration than reality. Despite its legislated independence, the Fed has been repeatedly subject to political criticism from both the president and Congress, both of whom have attempted to influence policymaking.

Central Bank Independence: History of an Idea

The earliest mention of CBI that we have been able to identify is Milton Friedman’s 1962 essay titled “Should There Be an Independent Monetary Authority?” Friedman states that the central bank should be organized with the “objective of a monetary structure that is both stable and free from irresponsible government tinkering” (p. 224). He considered three organizing structures beginning with a commodity standard, which he dismissed because a fully automatic standard is not feasible in a complex banking system. Recall that Friedman was writing at a time when the Bretton Woods system tied currency values to the dollar and the dollar to gold.

Friedman (1962: 224) then turns to the idea of an independent central bank and notes that “so far as I know, these views have never been fully spelled out,” which leads us to suspect that the term CBI originates with Friedman. A central bank exists with “a kind of monetary constitution” that specifies its objectives and tools and establishes a bureaucracy to carry out the mandate. An independent central bank is one whose mandate — to achieve responsible control of monetary policy — is unaffected by anything the government might do. An independent central bank would “not be subject to direct control by the legislature” and presumably the executive as well. In Friedman’s argument, a completely private-sector central bank, like the prewar Bank of England, might have such characteristics, although Parliament could always revoke its charter, just as government could change the underlying monetary constitution of an independent central bank. Regarding independent central banks, Friedman (1962: 226–27) avers:

It seems to me highly dubious that the United States, or for that matter any other country, has in practice ever had an independent central bank in this fullest sense of the term. Even when central banks have supposedly been fully independent, they have exercised their independence only so long as there has been no real conflict between them and the rest of the government. Whenever there has been a serious conflict, as in time of war, between the interests of the fiscal authorities in raising funds and of the monetary authorities in maintaining convertibility into specie, the bank has almost invariably given way, rather than the fiscal authority.

Thus, the irony of Friedman’s ground-breaking effort to define CBI is that he rejects it. He finds it intolerable “in a democracy to have so much power concentrated in a body free from any kind of direct, effective political control” (p. 227). Friedman concludes that an independent central bank with “wide discretion to independent experts” (p. 239) is not the answer. Instead he prefers his third organizing structure — namely, legislation that specifies the rules for the conduct of monetary policy and restricts the central bank’s discretion.1 Rules maintain public control through the legislative process and insulate policy from the whims of politicians.

All in all, Friedman (1962) provided us with a durable definition of CBI — a monetary constitution that defines the objectives of the central bank and establishes an organizational structure that can use policy instruments to pursue those objectives independent of political interference. However, his definition includes a prescient warning that independence exists only so long as there is no real conflict between the central bank and the government. Nevertheless, the idea that a central bank should be able to exercise its policy discretion in pursuit of the goals stipulated by political authorities became a virtually uncontested tenet of modern policymaking.

The arguments in favor of an independent central bank began to crystallize in the 1980s after a decade or more of traumatic inflationary experience that put a spotlight on central bank policymaking and its failures.2

CBI came into prominence as a result of four disparate and largely simultaneous influences. First, the inflationary episodes of the 1970s led to a great deal of dissatisfaction with central banks, which were blamed for allowing it to happen. Central bank organization, governance, and policymaking needed to be rethought. Second, central banks were being established or reconstituted in many countries — in developed countries, newly independent countries, and later, in the transition countries. In every instance, the role and position of the central bank in government structures (Friedman’s monetary constitution) needed to be defined. Third, the rational expectations revolution in macroeconomics led to major changes in thinking about the role of monetary policy. Last, initial empirical investigations suggested that countries with more independent central banks seemed to experience less inflation. By 1990 or so, these four influences came together resulting in the universally held conclusion that central banks should be independent of political influence.

Inflationary Episodes of the 1970s

The inflationary experiences of the 1970s were economically disruptive, politically unappealing, and hard to eradicate. It was appealing to blame central banks and to suggest changes in their governance as a solution. For example, the Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker changed its policy procedures in 1979 in order to address the persistent high inflation. The difficulty in bringing inflation under control made central bank operations more than a matter of technical interest for the first time.

Policy Role of Central Banks

The policy role of central banks only came into focus in the 20th century. Although some central banks have been around for a long time (notably the Rijksbank was founded in 1668 and the Bank of England in 1694), many central banks are of more recent vintage and many started as private institutions. The Federal Reserve opened in 1914 and the Bank of Canada in 1934; the Reserve Bank of India and the Central Bank of Argentina started in 1935 as private institutions. The formal role of central banks and their relationship to the government evolved slowly. Further, in the postwar period, many newly independent countries established central banks and had to define their relationship to the government and planning mechanisms. Finally, many more central banks were formed or reconstituted when transition began around 1989. Thus, there was considerable interest around the world regarding the monetary constitution.

Macroeconomic Modeling

Developments in macroeconomic modeling in the 1970s — including the natural rate of unemployment, the expectations-augmented Phillips curve, and rational expectations — had implications for understanding what a central bank can accomplish. This literature related to the conduct of central banks because policymakers could temporarily bring the unemployment rate below the natural rate by surprising the public with a policy expansion.3

Time inconsistency suggested the existence of a political business cycle where elected officials might take advantage of policy surprises to secure reelection.4 That an opportunistic policymaker can temporarily achieve a low unemployment rate is the basis of the time-inconsistency problem. The policymaker facing an election will have an incentive to introduce an expansionary monetary policy that will reduce unemployment in the short run. The fact that the effect will be temporary and that, in the long run — presumably after the elections — there will be an increase in inflation, and unemployment will return to the natural rate, is of no concern. Since the dynamics of unemployment and inflation effects are different, the elected official has an incentive to follow a short-run policy. Of course, the opportunistic central bank will quickly lose credibility and its ability to control inflation will rapidly erode, which was the experience in the 1970s.

The macrotheory arguments for CBI were strong. It insulates policy from the temptation to exploit political business cycles and also protects against the temptation that governments have to finance their activities by printing money. The advantages of delegating monetary policy to an independent body are strong enough to do so in a democratic society (Drazen 2002).

Empirical Investigations of CBI and Inflation

Finally, the rise of CBI to prominence was driven by empirical work that defined and measured central bank independence and looked at the relationship of CBI with inflation. Parkin and Bade (1978) were the first to measure CBI as indicated in central bank laws, but they only examined 12 major countries and their results did not attract much attention. A few additional papers looked at the relationships but with similarly small samples, rudimentary measures of CBI, and uncertain results (see Parkin 2013).

Cukierman, Webb, and Neyapti (1992) attracted more attention with their results based on detailed data on the characteristics of central banks for 72 countries for the entire postwar period. Along with Alesina and Summers (1993), their work went a long way toward canonizing the empirical observation that more independent central banks do a better job at controlling inflation. These studies introduced broader measures of CBI that included observed characteristics as well as legal structures.

The empirical relationship is complex and some authors challenge the accepted wisdom (see de Haan et al. 2018 and Parkin 2013 for references). First, the construction of indexes of independence involves arbitrary weightings regarding the relative importance of central bank characteristics and judgments regarding the extent of independence conveyed by components of the index. Second, the results are often sensitive to the composition of the sample; the negative relationship is strong among developed countries but less so among emerging market countries. Third, the measures of legal independence might have little to do with actual independence. The latter is hard to measure: indexes use survey responses or limited objective measures such as the tenure (or turnover) of central bank governors to measure functional independence. Fourth, CBI can be endogenous, reflecting the influence of a strong (anti-inflationary) financial sector or associated with strong, accountable, transparent democratic institutions in advanced countries. Acemoglu et al. (2008) show numerous instances where central bank reforms that increased measured CBI were put in place after or as inflation subsided. Finally, the relationship is complicated over time as many countries have responded to the canonization of CBI by changing their central bank laws. Central banks are far more independent now than they were in the 1980s (Crowe and Meade 2007).

From the very start, the proponents of CBI were aware of these shortcomings and tried to address them. However, it is interesting to note that the empirical evidence is rather shaky for a relationship that has been extremely influential to policymakers and thinking about monetary policy. Econometric results can be important even when they are weak.5

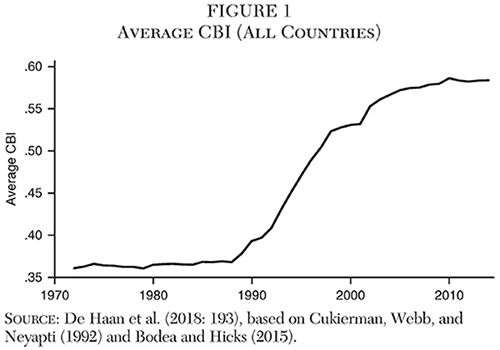

The compelling case for CBI influenced governments around the world. In the 1990s, the mean CBI index around the world rose rapidly and substantially as seen in Figure 1 from de Haan et al. (2018). The figure shows the average for all countries of the CBI index constructed by Cukierman, Webb, and Neyapti (1992) and updated by Bodea and Hicks (2015). The index ranges from zero to one and is based on indicators in four broad categories: the central bank chief executive, policy formation, central bank objectives, and limitations on lending to government. For example, a central bank is more independent if the governor has a long term and is responsible for formulating monetary policy, and if the central bank has a low inflation objective and cannot lend directly to the government. The increase in the CBI index in the 1990s was seen all over the world but most noticeably in transition countries and in Latin America.

In summary, CBI moved to the forefront due to four factors: (1) reactions to high inflation experiences; (2) interest in central bank legislation and constitutions and the establishment of many new or reconstituted central banks; (3) developments in macroeconomics, particularly rational expectations and time inconsistency; and (4) empirical evidence. All of these combined to build a convincing case that CBI is essential to constrain political influence and provide sound monetary policy. By the turn of the century, there was a strong consensus view among economists, central bankers, and governments in support of CBI. Central bankers found that CBI gave them the ability to ignore criticism and maintain policies consistent with long-run objectives.6

Contemporary Role of Central Bank Independence

Before we show how the narrow view of CBI geared to macroeconomic monetary policy has been challenged by the global financial crisis, consider its role in emerging countries. There are several additional arguments to make in favor of CBI in emerging markets. Central bankers in emerging markets might have an advantage over their advanced economies peers in defending independence. They should just point out that central bank independence (real or perceived) has much larger positive effects in emerging markets than in advanced ones. Those effects stem from three sources:

- Institution Building. The need to build, strengthen, and protect institutions in emerging markets is at the core of practically all development strategies. The independence of central banks and their professed success became a benchmark in institutional progress and served to reinforce and emphasize the role of good institutional structures. It definitely helped to buttress the claims for judicial independence, for example, and to gain increasing support for the respect that is due to these concepts as part of the reform process.

- Human Capital Accumulation. There is one aspect of independence that has spread quite generally: within certain parameters, almost all central banks have enough independence to manage their own budgets (or to fight for doing so). That fact allows central banks to attract, train (domestically and abroad), and preserve a highly qualified professional staff (usually the best in the public sector). While this is true also in advanced countries, the impact that such staff has on the rest of the economy is more acute in countries where such skills are scarcer. This observation could be used to defend central bank independence but should be utilized with care to avoid the identification of central bank staff with one of the “elites” that have been made responsible for recent crises.

- The “International Club” Effect. Central banks tend to be more closely associated with their colleagues across the world than other institutions. They have their own international gathering place (the Bank for International Settlements [BIS] in Basel), are very active in multilateral institutions, and are members of many regional groups. They serve as a channel for the transmission of good practices and for the introduction of better transmission mechanisms. They also “protect” each other by publicizing abuses in some circumstances. Central bankers gain stature in the eyes of the local markets by interacting with their peers in the international arena. And independence, real or not, increases the standing of central bankers in their own eyes — difficult to measure but important in the reality of competitive markets and credibility building.

In summary, central bank independence (or even the perception of it) is not to be taken for granted in emerging market countries. However, contemporary arguments in favor of maintaining CBI in advanced economies are more nuanced.

There are three complex and closely related central bank functions: (1) setting monetary policy to attain macroeconomic goals; (2) providing a lender-of-last-resort facility to financial institutions; and (3) maintaining the stability of the financial system as a whole. Historically, central banking started with Bagehot’s lender of last resort. However, the lending and stability functions were almost forgotten in the calm of the postwar period as central banks emphasized macroeconomic monetary policy.

By the end of the 20th century, an idealized notion of central banking emerged. The modern central bank was an institution independent of government influence with a single mandate — to conduct monetary policy in order to maintain price stability. In some countries, notably the United States, there was a dual mandate — price stability and maximum feasible growth. But the idealized notion paid little attention to the stability or crisis-lending functions of the central bank. A narrow view of CBI emphasized monetary policy to the virtual exclusion of the other roles. Writing after the crisis, Stanley Fischer (2015) distinguished between “monetary policy independence” and “central bank independence.” Although always implicit, the distinction was lost in the 1990s, perhaps because the nonmonetary policy roles of central banks fell into disfavor.

In the United States, the eminent monetary historian Anna J. Schwartz (1992: 68) concluded: “A Federal Reserve System without the discount window would be a better functioning institution.” Her conclusion followed from the fact that the Fed’s discount window was sometimes misused to support insolvent institutions (in violation of Bagehot’s dictum). Furthermore, the discount window was viewed as unnecessary because liquid and deep money markets provided adequate private-sector alternatives.7 In the United Kingdom, all regulatory and supervisory functions were separated from the central bank and moved to the Financial Services Agency from 2001–13. This change had disastrous consequences during the financial crisis because the Bank of England was not sufficiently well informed about banks in distress.

Both Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke thought that the Fed should not respond to asset price bubbles because they are hard to predict and the tools to prick them selectively are lacking. Instead, the role of the central bank was to “mop up after the bubble burst.” Thus, the central bank was implicitly ignoring the risk of financial instability and would only tend to the macroeconomic aftermath of a crisis.

Although the term “macroprudential policy” had been introduced by economists at the BIS in the 1980s, there was little discussion of financial stability issues. This is surprising in retrospect because crises occurred amidst the prevailing stability in both developed and emerging economies. For example, both Finland and Sweden experienced costly systemic banking crises in the 1990s. Many Asian economies suffered financial crises in 1997, with serious impact on the real economy. The emphasis on narrow form CBI and macroeconomic monetary policy made developed economies vulnerable and central banks ill prepared to address financial stability.

The 2007-09 crisis experience challenged the holy grail of CBI. The crisis responses placed limits on CBI although there has been no formal retreat in the indexes that measure CBI. Governments rather than independent central banks were the primary decisionmakers in crisis responses including the use of TARP funds in the United States and the takeover of Northern Rock and RBS in the United Kingdom. The European Central Bank (ECB) was established in the heyday of CBI, and Article 130 of the Maastricht Treaty enshrines a very formal conception of the bank’s independence. However, the role of the ECB expanded in two significant ways during the crisis: it was a given a role in bank supervision and a role in providing financial assistance to certain member states. The expanded role calls for a redefinition of independence (see Mersch 2017) and suggests that CBI might not be immutable but evolutionary.

As noted earlier, CBI was developed with the monetary policy role first and foremost. Some (postcrisis) reflection on the three roles of the central bank suggests that they are inseparable and call for a nuanced understanding of CBI. The lender-of-last-resort function is a banking function. The central bank is lending to a customer, and just like any bank, it needs to know its customers. Thus, the central bank has a role in bank supervision partly because it should be familiar with the condition of its potential loan customers. Further, it should be able to maintain some secrecy regarding lending so that solvent banks that borrow from the central bank are not stigmatized or subject to runs. To conduct its banking functions, particularly in a crisis, the central bank needs to operate independently and sometimes out of the public eye.

However, when a systemic crisis looms, lending can go beyond Bagehot’s dictum and represent a decision to bail out or at least support financial institutions in jeopardy of failing with systemic consequences. In that case, the lending is a form of government support or an expenditure for a specific activity. Bailouts are a fiscal decision — a government expenditure that should be subject to political oversight or input. In fact, the crisis responses of the Fed, the Bank of England, and the ECB among others included fiscal decisions and extensive cooperation between the formally independent central banks and their governmental partners.

Crisis responses challenge CBI and bring the central bank closer to the government in two ways. First, as just noted, a bailout can involve a fiscal decision that is the purview of the political structure. Second, bailouts, other crisis responses, and macroprudential policies designed to maintain stability can all have distributional implications. Particular activities (e.g., targeting loans to specific sectors) or particular institutions will be affected differently. Such asymmetries fall in the realm of political decisionmakers.

As a consequence of the crisis experiences, discussion of the principles of central bank governance has moved away from CBI and now emphasizes goal setting, transparency, and accountability.8 It could well be that independence is not important if these other features are in place as suggested empirically by Campillo and Miron (1997). Another reason why CBI might be less important in the postcrisis environment is that low inflation makes time inconsistency less relevant.9

For monetary policy, the line between CBI and the role of government was helpfully drawn by Debelle and Fischer (1994), who introduced the distinction between goal and instrument independence. The goals of the central bank are the prerogative of the political establishment. CBI then means that the central bank should be able to decide how to use its policy instruments in order to attain those goals. Simply speaking, Congress set down the goals of stable prices and maximum feasible employment and the Federal Reserve sets its policy instruments in order to attain the goals.

As we have seen, the financial crisis added, implicitly if not explicitly, a third goal — namely, financial stability. In this case, the goal is harder to define operationally and the relationship to instruments is less well understood. Some stability actions (e.g., a bailout) are one-off decisions that involve a political decision and some involve policy tools (e.g., macroprudential regulation) that are still being developed. The implication is that the goal of financial stability involves close interaction between the independent central bank and the government; CBI cannot be cleanly separated from the country’s political institutions.10

With all our admiration for CBI and the role it plays in maintaining global price stability and bringing about good governance, central banks are part of the government and have always been involved in the give and take of politics. It is silly to pretend that there is an ideal of CBI that sets them apart. This was a lesson of the financial crisis but, interestingly, it was always true. The idealized version of CBI was not really descriptive of the world inhabited by even the most independent central banks.

Even narrow-form CBI (i.e., independence to conduct monetary policy) is often subject to government interference. When the full range of central bank functions are considered, the central bank is often in a position where it must interact, coordinate, seek approval, or otherwise engage with the government. There are numerous examples of central bank engagement with the government, even with regard to monetary policymaking. In the next section, we provide an overview of the Federal Reserve’s postwar history. CBI notwithstanding, the Fed has always interacted with political authorities. CBI does not mean that the central bank exists in a vacuum.

Postwar CBI in the United States

Every postwar president from Truman to Trump has made an effort, not always successfully, to influence monetary policy (Conti-Brown 2016). Furthermore, Congress — sometimes from the left, sometimes from the right — often has the Fed in its sights (Binder and Spindel 2017; Paul 2009; Wachtel 2017). The statutory independence of the Fed is clear but that does not mean it is removed from political influence or criticism that might influence decisionmaking (Cargill and O’Driscoll 2013).

The Federal Reserve began operating in 1914 as a group of 12 regional banks with weak oversight from the Board of Governors in Washington, D.C. Independence was reinforced in the 1930s with the establishment of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) and the removal of the Secretary of the Treasury from the board. During World War II, everyone agreed that the role of the Fed was to assist in war financing with low interest rates. The Fed continued to peg long-term interest rates at 2.5 percent even as inflation accelerated in the postwar period. Low interest rates were popular and the policy record indicates that the Treasury was in charge; the Fed had little will or desire to resist. As inflation increased during the Korean War, the Fed was ready to tighten policy and assert its independence.

In January 1951, President Truman met with the chair of the Federal Reserve Board and the Secretary of the Treasury and announced afterward that the Fed would support administration policies. Further, the Treasury added that interest rates would not change for the duration of the conflict. A virtual war erupted between the Fed, which thought that its powers had been usurped, and the executive. A few weeks later, Truman called the entire FOMC into the White House for a meeting. The dispute ended in March 1951 with the Fed-Treasury Accord, an agreement affirming that the Fed would assure the government’s ability to finance the war and at the same time minimize the monetization of the debt. The Fed took this to mean that it was free to conduct monetary policy to combat inflation. The accord was a singular event that affirmed the independence of the Fed, although President Truman did not think that the Fed should have absolute monetary independence.

The accord did give the Fed its operational independence, but it by no means ended presidential interference with the conduct of monetary policy. Tax cuts and spending on military operations in Vietnam led the Fed to raise interest rates in December 1965, which angered President Johnson. He called the board chair and other officials to his Texas ranch to criticize monetary policy. Although the Fed stood its ground, the president did not readily accept CBI and tried to influence policymaking (Fessenden 2016).

An important instance of political influence over Fed policy involves President Nixon and Board Chairman Arthur Burns. Burns was a prominent academic economist and a Republican activist who managed Nixon’s 1968 campaign. He remained close to Nixon after he was appointed chairman of the Board of Governors. Monetary policy was expansionary in 1970 and 1971 and the economy grew rapidly in 1972, while inflation was temporarily restrained by wage and price controls that had been introduced in August 1971. Nixon was reelected by a wide margin in November 1972.

Even at the time, observers wondered whether the loose policy was an effort to ensure Nixon’s reelection or a policy error, perhaps an honest misjudgment regarding the effects of price controls, (Cukierman 2010). The issue was clarified when the tapes of Nixon White House conversations were released. Abrams (2006) finds several conversations showing efforts by Nixon to influence Burns. Although it is impossible to tell whether Burns’s policy decisions were determined by electoral considerations, it is clear that the president made every effort to influence the Federal Reserve.

Direct interactions between the president and the chairman of the Board of Governors continue today. President Trump has made repeated public criticisms of the Fed in recent months. Using Twitter, he commented on December 24, 2018, after an increase in the fed funds target, “The only problem our economy has is the Fed.” More specifically, on April 30, 2019, President Trump tweeted:

Our Federal Reserve has incessantly lifted interest rates, even though inflation is very low, and instituted a very big dose of quantitative tightening. We have the potential to go … up like a rocket if we did some lowering of rates, like one point, and some quantitative easing. Yes, we are doing very well at 3.2% GDP, but with our wonderfully low inflation, we could be setting major records &, at the same time, make our National Debt start to look small!

It is impossible to judge whether these recent efforts to influence policymaking have any effect on FOMC discussions or decisions. It is clear that President Trump follows some of his predecessors by having little confidence in CBI. The barrage of criticism makes it more difficult for the Fed to conduct monetary policy and might also erode public trust in the institution.

There does not appear to be any time in the postwar era where the Fed has not been subject to congressional criticism, including threats to take away its independence. Criticism of the Fed has come from the left and from the right, but there has always been criticism of policy and the structure of the central bank. It is impossible to judge whether the criticism, introduction of restrictive legislation and threats have influenced policy, but it does pull the Fed off its perch of independence and into politics. The discussion is unrelenting and it is hard to imagine that the Fed is impervious to political winds around it.

Wright Patman, a populist Texas democrat, spent a long career in the House of Representatives berating the Federal Reserve for keeping interest rates too high (Todd 2012). More substantive criticism came from Hubert Humphrey in the 1970s. Humphrey was a liberal Democratic senator from Minnesota and presidential candidate who sought to place monetary policy under closer, even direct, congressional supervision, because he thought that the Fed paid too little attention to the full employment mandate set out in 1946.11

With the U.S. economy suffering from stagflation, there was considerable interest in Congress to do something or at least to have the Fed do something. Although there was not sufficient support for any legislative change, a “concurrent resolution” (H. Con. Res. 133) in 1975 declared (without any legal force) that the Fed should report its policy moves and money supply targets to Congress regularly. Although this was an attack on the Fed’s independence, it was also the first move toward accountability.

Criticism of the Fed’s inability to control inflation and the intellectual ascendancy of monetarism led to legislative changes in 1977. The dual mandate (maximum employment and stable prices) was formally established, and the Fed was required to report to Congress regarding its policymaking. Prior to that, the Fed, like other central banks, largely operated in secret. Secrecy about short-term intentions — and even about actual policy changes — was thought to preserve the Fed’s discretion and influence over financial markets.

The Reform Act of 1977 increased congressional oversight by requiring the Fed to “consult with Congress at semiannual hearings about the Board of Governors’ and the Federal Open Market Committee’s objectives and plans with respect to the ranges of growth or diminution of monetary and credit aggregates for the upcoming twelve months, taking account of past and prospective developments in production, employment, and prices.” Congress specified a policy approach, a monetarist emphasis on growth targets and formalized accountability for the first time. However, it went on to add: “Nothing in this Act shall be interpreted to require that such ranges of growth or diminution be achieved if the Board of Governors and the Federal Open Market Committee determine that they cannot or should not be achieved because of changing conditions.”12 A year later, the Humphrey-Hawkins Act called for a broader written report, the semiannual “Monetary Policy Report to Congress” on both monetary policy and macroeconomic performance. These reports continue today, long after the legislated requirement expired (in 2000) and monetary growth targets were abandoned.13

Another element of congressional oversight introduced in the 1977 Reform Act made the president’s designation of the chairman and vice chairman of the Federal Reserve Board (from among the governors) subject to Senate confirmation and introduced a four-year term. This tied the appointment of the leading policymakers to the political cycle. Unlike his predecessors for several decades, President Trump declined to reappoint a board chair originally selected by President Obama.

These 1970s reforms were a reflection of congressional criticism and a desire to rein in or take control of the Fed. However, the steps taken did not reduce formal Fed independence in any significant fashion. Of greater consequence were the changes that forced the Fed toward greater transparency. Increased transparency and accountability are now viewed as important features of good policymaking. Transparency and communication are the modern hallmarks of good central banking, perhaps more so than independence.14

Congressional criticism of the Fed shifted across the aisle around the turn of the century. The gadfly of note was Ron Paul, a Republican congressman from Texas, who wrote a book called succinctly, End the Fed, and ran for president on that issue. His support for legal challenges to the constitutionality of the independent central bank, introduction of a gold standard, and congressional audits of all policymaking activity were not taken seriously by many. Nevertheless, they may well have been influential; Paul’s anger at the Fed resonated with many during the financial crisis.

After the crisis, the landmark 2010 Dodd-Frank Act introduced extensive changes to financial regulation but did not change the way monetary policy is conducted. Early drafts of the act included adding a goal — maintaining financial stability — to the dual mandate but it is not part of the act. However, the act introduced new Fed functions and responsibilities that make such a goal implicit, and the Fed’s own mission statement does include “maintaining the stability of the financial system and containing systemic risk that may arise in financial markets.”15 Nevertheless, Dodd-Frank placed severe limits on the ability of the Fed to use its lending authority in response to crisis. Thus, it limits CBI with regard to the Fed’s financial stability goals.

The Fed made vigorous use of its lending authority as the financial crisis unfolded, some of it under its emergency lending authority. Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, which had not been used in modern times, stated that, in “unusual and exigent circumstances,” the Fed could lend to just about any institution. The use of emergency lending in the crisis generated a great deal of controversy.16 Even some officials in the Federal Reserve were uncomfortable with the use of 13(3) lending authority to support “too-big-to-fail” institutions. Charles Plosser (2010: 11), then the president of the Philadelphia Fed, argued that “Such lending should be done by the fiscal authorities only in emergencies and, if the Fed is involved, only upon the written request of the Treasury.”

The negative public reaction to the Fed’s “bailouts” resulted in provisions in Dodd-Frank designed to restrict the use of section 13(3) emergency lending, which had been very open ended.17 This was a significant reduction of CBI, albeit with regard to crisis response rather than monetary policy. Proponents of Dodd-Frank argued that other provisions, such as the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), mitigated the restrictions on emergency lending. Significantly, FSOC is chaired by the treasury secretary and includes, in addition to the chair of the Federal Reserve Board, other financial sector regulators and an independent member appointed by the president. The awkward structure of FSOC runs the risk of delaying and politicizing decisionmaking — just the opposite of what would be desirable in a crisis. In the Trump administration, FSOC has removed the SIFI (systemically important financial institutions) status of several banks and nonbanks, thereby weakening the new Dodd-Frank safeguards. Whether the crisis response mechanisms work or not is yet to be seen, but it is clear that crisis response has been pulled back to the political world — it is not the exclusive purview of the independent central bank.

The Fed was also criticized for the secretiveness of its actions during the crisis. As a result, Dodd-Frank also requires full public disclosure, with a time delay, of the terms and details of all Fed transactions. While transparency is valuable, the detailed disclosure policies (even with a lag) might inhibit the Fed’s willingness to use its lending authority in a crisis.

Dissatisfaction with an independent central bank did not end with the passage of Dodd-Frank. Until the 2018 election, Texas Republican Jeb Hensarling chaired the House Financial Services Committee. Under his leadership, the House of Representatives approved the Financial CHOICE Act, which warrants a close look even though there is no current likelihood that it will move forward in the current Congress.

From start to finish, the CHOICE Act provisions that relate to monetary policy reflect anger at the Fed’s history and practice (see Wachtel 2017). There is an underlying motif that the Fed consistently does the wrong thing and needs to be admonished and controlled; it is an institution that cannot be trusted. Short of replacing it with some other institution, the act attempted to place monetary policy on a short leash and under a degree of scrutiny that would clearly compromise the independence of policymakers. The independent central bank would be subject to constant detailed oversight from Congress and the executive branch that is designed to influence policy and limit CBI.

All previous legislation has been consistent with the principle that Congress sets the objectives of policy (the central bank does not have goal independence) and the central bank determines how best to achieve the goals (instrument or operational independence). The CHOICE Act takes a drastically different approach: it specifies a fixed reference rule as a benchmark for assessing monetary policy and introduces complex procedures for GAO (Government Accountability Office) and congressional oversight of the Fed’s policymaking or adherence to that rule. The act specifies the well-known Taylor Rule as the determinant of the policy interest rate, and the legislation includes data definitions and coefficients as if an economics research paper is being presented in legislative language.

There is a long history of economists who support the use of policy rules for monetary policy. Our discussion began with Milton Friedman’s (1962) disdain for central bank independence. He was arguing for a rule and would probably support this legislation. A rule provides the public with a context for understanding policy decisions and interpreting the intermediate-term objectives of policy. A publicly known rule makes the central bank’s objectives clear and shows how it will use its policy targets to achieve those objectives. Importantly, a rule also helps the policymaker to maintain a stable policy designed to achieve long-term objectives. In an ideal world, the rule guides policy and provides the public with a full understanding of policy decisions, thus enhancing economic stability and confidence. Monetary policy should be systematic, predictable, and focused on its long-run objectives; a rule can be a useful part of a communication strategy as it does not preclude the ability of policy to respond flexibly in certain instances.

The upshot of this discussion is that CBI in the United States cannot be taken for granted. Presidents have tried to influence the Fed and Congress seems to be perpetually at odds with the idea of CBI. In fact, congressional challenges to CBI in the 1970s and 1980s were beneficial in that they forced the Fed to start considering the value of accountability and transparency in policymaking. In the postcrisis period, the independence of the Fed to take action in crisis situations has been compromised.

A similar observation can be made in Germany regarding the Bundesbank, which was renowned for its emphasis on price stability. Its ability to follow this hardline approach was a reflection of German political values as much as a consequence of CBI. In other instances, when the Bundesbank’s policy views differed from those of the government, the political decisionmaker prevailed. Specifically, the Bundesbank objected to the ostmark conversion in 1989, opposed providing support for the French franc in 1992–93, and was not keen on joining the eurozone a decade later. In every instance, the government prevailed.

The Fed and the Bundesbank (and its successor, the ECB) may have substantial monetary policy independence, though it is impossible to determine whether policymakers are affected by political criticism and pressure. However, CBI is not absolute since central banks are increasingly involved in other policy actions related to a financial stability mandate and these actions often have fiscal and political implications. In this regard, there is often conflict with government policy, and as Friedman suggested a half-century ago in the quotation shown earlier (Friedman 1962: 226): “Even when central banks have supposedly been fully independent, they have exercised their independence only so long as there has been no real conflict between them and the rest of the government.”

Conclusion

Central bank independence, like the law of comparative advantage or the role of money in inflation, is part of the accepted wisdom of modern economics. It attained that elevated status around 1990 and led to an idealized view of central banking. The ideal central bank was an institution that was free of any political influence so it could use monetary policy instruments to pursue price stability or an inflation target.

The idealized view was thrust forward by four developments in the 1970s and 1980s. First, central banks of most major economies were unable to curb the inflationary outbursts in the 1970s associated with oil price shocks. Second, the macro literature developed a firm theoretical basis for understanding time inconsistency and why governments might exhibit an inflationary bias. Third, central banking laws were being introduced in many countries, sometimes for the first time (in newly independent countries and emerging markets) and sometimes being modernized as central banks moved from a private-sector role to a clearly defined relationship to the government. Finally, characteristics of central bank organization and governance were used to construct indexes of CBI that seem to correlate with inflation experience. The simple correlation of “more CBI with less inflation” seemed to provide the finishing touch on the canonization of CBI. Governments around the world took note of these developments, and legislated changes to give central banks more independence were common through the 1990s.

In some important respects, the rise of CBI was and continues to be very valuable. It contributed to the global disinflation of the period. And, in emerging markets, CBI had externalities that influenced the quality of governance generally. In developed economies, CBI contributed to a very narrow view of central bank functions, which made economies more vulnerable to crisis. The rise of CBI coincided with the era when the monetary policy functions of the central bank were paramount and other roles receded into the background.

A decade past the financial crisis, there is a different view of CBI that recognizes the constraints on CBI. Insofar as monetary policy is concerned, it is still widely accepted that the policy tools should be set by a policy committee that is independent of political influence. But even then, monetary policy might have political implications. For example, at the zero lower bound, asset purchases by the central bank can have distributional impacts that can involve political choices.

However, the regulatory, lending, and stability functions of the central bank came to the forefront very quickly during the financial crisis. Crisis responses — whether to intervene and support institutions — have distributional implications and also involve fiscal expenditures. These are inherently political decisions that should not be left to unelected bodies. The modern view of constrained CBI recognizes that central banks must often work with or listen to political authorities.

The modern central bank is a more complex institution whose responsibilities overlap with other government functions. Central bank efforts to avoid a systemic crisis might involve fiscal or expenditure decisions and have distributional implications that are political in nature. Crisis response cannot be totally independent of political decisionmaking. Central banks and governments have not entirely sorted out how to maintain the balance between political responsibility and independence for central banks with a broad mandate. Buiter (2014) warns that CBI will only be maintained if a clear distinction is drawn between the monetary policy and liquidity provision functions of a traditional central bank and other policy interventions with fiscal and distributional consequences. Governance structures that provide adequate crisis responses by an independent central bank and respect the role of political decisionmaking in bailouts have yet to be developed. Thus, CBI is a more nuanced and complex concept than it seemed 30 years ago as the role of central banks evolve.

References

Abrams, B. A. (2006) “How Richard Nixon Pressured Arthur Burns: Evidence from the Nixon Tapes.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 20 (4): 177–81.

Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Querubin, P.; and Robinson, J. A. (2008) “When Does Policy Reform Work? The Case of Central Bank Independence.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 39: 351–429.

Alesina, A., and Summers, L. (1993) “Central Bank Independence and Macroeconomic Performance: Some Comparative Evidence.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 25 (2): 151–62.

Binder, S., and Spindel, M. (2017) The Myth of Independence: How Congress Governs the Federal Reserve. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Bodea, C., and Hicks, R. (2015) “Price Stability and Central Bank Independence: Discipline, Credibility, and Democratic Institutions.” International Organization 69 (1): 35–61.

Buiter, W. (2014) “Central Banks: Powerful, Political and Unaccountable?” CEPR Discussion Paper DP10223 (November 17).

Buol, J., and Vaughan, M. (2003) “Rules vs. Discretion: The Wrong Choice Could Open the Floodgates.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Regional Economist (January).

Campillo, M., and Miron, J. A. (1997) “Why Does Inflation Diverge across Countries?” In C. D. Romer and D. H. Romer (eds.), Reducing Inflation: Motivation and Strategy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cargill, T. F., and O’Driscoll., G. P. Jr. (2013) “Federal Reserve Independence: Reality or Myth?” Cato Journal 33 (3): 417–35.

Conti-Brown, P. (2016) The Power and Independence of the Federal Reserve. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Crowe, C., and Meade, E. E. (2007) “The Evolution of Central Bank Governance around the World.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 21 (4): 69–90.

Cukierman, A. (2010) “How Would Have Monetary Policy During the Great Inflation Differed, If It Had Been Conducted in the Styles of Volcker and Greenspan with Perfect Foresight.” Comparative Economic Studies 52 (2): 159–80.

Cukierman, A.; Webb, S. B.; and Neyapti, B. (1992) “Measuring the Independence of Central Banks and Its Effect on Policy Outcomes.” World Bank Economic Review 6 (3): 353–98.

Debelle, G., and Fischer, S. (1994) “How Independent Should a Central Bank Be?” In J. C. Fuhrer (ed.), Goals, Guidelines and Constraints Facing Monetary Policymakers, 195–221. Conference Series No. 38. Boston: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

de Haan, J.; Bodea, C.; Hicks, R.; and Eijffinger, S. (2018) “Central Bank Independence Before and After the Crisis.” Comparative Economic Studies 60: 183–202.

Dennis, R. (2003) “Time-Inconsistent Monetary Policies: Recent Research.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter No. 2003-10 (April 11).

Drazen, A. (2001) “The Political Business Cycle After 25 Years.” NBER Macroeconomics Annual 15 (2000): 75–138.

_________ (2002) “Central Bank Independence, Democracy, and Dollarization.” Journal of Applied Economics 5: 1–17.

Fessenden, H. (2016) “1965: The Year the Fed and LBJ Clashed.” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Econ Focus (Third-Fourth Quarter): 4–7.

Fischer, S. (2015) “Central Bank Independence.” Available at www.bis.org/review/r151109c.pdf.

Friedman, M. (1962) “Should There Be an Independent Monetary Authority?” In L. B. Yeager (ed.), In Search of a Monetary Constitution, 219–43. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

_________ (1982) “Monetary Policy: Theory and Practice.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 14 (1): 98–118.

Geithner, T. (2005) “Perspectives on Monetary Policy and Central Banking.” Available at www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/speeches/2005/gei050329.

Goodman, J. B. (1991) “The Politics of Central Bank Independence.” Comparative Politics 23 (3): 329–49.

Labonte, M. (2016) “Federal Reserve: Emergency Lending.” Available at https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44185.pdf.

Mersch, Y. (2017) “Central Bank Independence Revisited.” Symposium on Building the Financial System of the 21st Century: An Agenda for Europe and the United States, Frankfurt am Main, March 30. Available at www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2017/html/sp170330.en.html.

Parkin, M. (2013) “Central Bank Laws and Monetary Policy Outcomes: A Three Decade Perspective.” University of Western Ontario, EPRI Working Paper No. 2013–1 (January).

Parkin, M., and Bade, R. (1978) “Central Bank Laws and Monetary Policies: A Preliminary Investigation.” In M. G. Porter (ed.), The Australian Monetary System in the 1970s, 24–39. Melbourne, Australia: Monash University.

Paul, R. (2009) End the Fed. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

Plosser, C. I. (2010) “The Federal Reserve System: Balancing Independence and Accountability.” Speech at the World Affairs Council of Philadelphia, February 17.

Powell, J. (2018) “Financial Stability and Central Bank Transparency.” Available at www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/files/powell20180525a.pdf.

Schwartz, A. J. (1992) “The Misuse of the Fed’s Discount Window.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review (September/October).

Summers, L. (2017) “Central Bank Independence.” Available at http://larrysummers.com/2017/09/28/central-bank-independence.

Todd, T. (ed.) (2012) The Balance of Power: The Political Fight for an Independent Central Bank, 1790–Present. Kansas City, Mo.: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Wachtel, P. (2017) “Monetary Policy and the Financial CHOICE Act.” In M. Richardson, K. Schoenholtz, B. Tuckman, and L. J. White (eds.), Regulating Wall Street: CHOICE Act vs. Dodd-Frank. New York: Stern School of Business, New York University (March).

_________ (2018) “Credit Deepening: Precursor to Growth or Crisis?” Comparative Economic Studies 60: 34–43.

Cato Journal, Vol. 40, No. 1 (Winter 2020). Copyright © Cato Institute. All rights reserved. DOI:10.36009/CJ.40.1.7.

Paul Wachtel is Professor of Economics at New York University Stern School of Business. Mario I. Blejer is Visiting Professor in the Institute of Global Affairs at the London School of Economics. This article builds on presentations by Wachtel at the Colloquium on “Money, Debt and Sovereignty,” Université de Picardie Jules Verne, December 11–12, 2017; the XXVI International Rome Conference on Money, Banking and Finance, LUMSA University, Palermo, Italy, December 14–16, 2017; and the Center for Advanced Studies on the Foundations of Law and Finance, Goethe University, May 20, 2019; and by Wachtel and Blejer at the Conference on Financial Resilience and Systemic Risk, London School of Economics, January 30–31, 2019; and the 25th Dubrovnik Economic Conference, June 15–16, 2019. This article is part of the LSE IGA Financial Resilience project supported by the Rockefeller Foundation.

1On the history of rules versus discretion, see Buol and Vaughan (2003).

2Friedman did not change his view that independence does not provide an adequate incentive to pursue monetary stability (see Friedman 1982).

3See Dennis (2003) for a short introduction and references to Finn Kydland and Ed Prescottt, and Robert Barro and David Gordon.

4See Drazen (2001) for a summary of the early literature and the contributions by William Nordhaus and Alberto Alesina.

5Another such example (Wachtel 2018) is the empirical work on the finance-growth nexus. It dates to the early 1990s and changed the way economists think about the influence of the financial sector on growth. The results from panel data studies were very influential but in many respects — appropriateness of the measures, sensitivity of the results, and lack of causality — not very strong.

6For a central banker’s explanation of the importance of independence, see Timothy Geithner’s address at the Central Bank of Brazil, a country that has suffered the consequences of nonindependence (Geithner 2005).

7The Fed did not follow Schwartz’s advice but instead took several steps in the 1990s to strengthen the discount window and encourage bank borrowing.

8See, for example, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell’s (2018) remarks at the conference on the 350th anniversary of the Sveriges Riksbank.

9Thanks to Vedran Sosic for pointing us to comments by Lawrence Summers (2017). However, low inflation may not be permanent.

10For an early recognition of this in the political science literature, see Goodman (1991).

11It is ironic that in the 1970s, the most liberal wing of Congress was eager to control the Fed, while 40 years later, it is the rallying cry of the most conservative elements. In fact, populist elements on both sides of the aisle — from Rand Paul to Bernie Sanders — are often critical of the Fed’s independence.

12Section 2A of the Act from https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/95/hr9710/text.

13The act required the Fed to report money supply target growth ranges to Congress at just the time when confidence in the efficacy of the monetarist approach was waning.

14The Fed itself did not start moving toward greater transparency and improved communication until the 1990s. It was only in 1994 that the Fed began to announce the numerical value of its fed funds rate target, and only in 2011 that the board chair began to hold a press conference after the FOMC meeting. The FOMC now regularly publishes forecasts for key economic variables, along with projections for the policy interest rate.

15See www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/mission.htm.

16The proper scope of emergency lending by the central bank and whether it should extend to nonbank entities is a difficult question that has been the subject of much debate (see Labonte 2016).

17The Dodd-Frank Act requires that emergency lending to nonbanks go only to those participating in a broad-based program. The provision was specifically designed to prohibit the extension of credit to individual nonbanks. It also introduced some external oversight of Fed lending. The original provision only required the approval of not less than five members of the Board of Governors, while Dodd-Frank requires prior approval by the Secretary of the Treasury. In addition, the act requires reporting to congressional committees within seven days of the use of 13(3) and allows for Government Accountability Office auditing.

Central bank independence (CBI) became a globally accepted truth of economics about 30 years ago. It is clearly valuable for ensuring that monetary policy is conducted in a way that is consistent with appropriate central bank objectives and free of political influences. Nevertheless, CBI has been under attack in both the developed world (President Trump is a frequent critic) and in emerging markets (e.g., in Turkey and India). Thus, the time is ripe to take a new look at CBI. An examination of its origins will provide a framework for examining its current status.

In this article, we examine how central bank independence became the cornerstone of central banking in the late 20th century and how the idea has been challenged by recent events. We find that in the developed world, the strong emphasis on CBI led to a narrow view of the role of central banks. As a result, central banks were unaware of financial stability risks and ill prepared to respond to the financial crisis. In the less-developed, emerging market world, CBI improved policy management and governance.

The arguments regarding CBI are focused on the monetary policy role of central banks that emerged in the post-World War II era as economists began to understand the importance of interest rates and credit aggregates to the macroeconomy. Historically, central banks, including some that were private-sector entities, were explicitly agents to carry out government policy (Parkin and Bade 1978). This would be true of the Bank of Japan and the Netherlands’ Bank among others. Other central banks, including the Swiss National Bank and the Bank of England, did not establish their statutory independence until recently.

The traditional view of central bank functions is associated with Walter Bagehot, the 19th-century British journalist who articulated the idea that a central bank should act as the lender of last resort to the financial system. By providing liquidity, the central bank can prevent crises and preserve stability. For example, the Fed was established as a lender, to use discounting to maintain financial stability (“furnish an elastic currency” in the words of the legislation). The lending functions of the Federal Reserve and other central banks diminished in importance through the latter half of the 20th century as macro monetary policy became the focus and new policy tools were developed. By the end of the 20th century, central banks were primarily associated with the macroeconomic policy role. However, the financial crisis of 2007-09 brought a renewed emphasis on the lender-of-last-resort function and the use of central bank lending to ensure financial stability.

While the overwhelming majority of academic and central bank practitioners continue to support central bank independence, it is clear that, while independence continues to be protected, its golden age ended with the crisis a decade ago, and it did not end gently. The first wave of charges against central banks was straightforward: the worst financial crisis since the 1930s took place after central bankers worldwide were handed, or thought they were handed, most of the economic-management levers and were given much discretion in the design and certainly the implementation of their economic policies. Given these perceptions, there is no way they can now avoid blame, and preserve intact their prestige and standing. Indeed, the reputation of “independent central bankers” was severely damaged by the crisis, removing partially the implicit taboo involved in asking the unmentionable: perhaps central banks should not be, nor should aim at being, so independent after all?

However, independence, at least formally, appears to be surviving. There was no lethal follow-up after the initial crisis-induced assaults. This restraint may have been the consequence of the fact that, one way or another, the crisis was controlled and central banks were instrumental in avoiding — with huge help from government and regulators — the complete collapse of the financial system. But the seeds of doubts about independence were planted and more questions and criticism continue to arise. Many claim that in the 2000s, central banks unwittingly fueled the credit expansion that resulted in the crisis. This bad press may eventually translate into the political arena, as voters are chasing those that are seen as responsible for the crash and the austerity policies that ensued.

Moreover, a crucial element in shielding central bankers from the popular wrath is also being questioned — namely, their success in achieving and maintaining price stability. The argument is that the central banks’ role in such success, although relevant, was overstated given the strong exogenous disinflationary consequences of technology and globalization. Even more serious is the near-consensus view that independent central banks spectacularly failed to achieve and preserve financial stability, just as crucial a mission as its macroeconomic companion.

Of course, nobody claims that a country where politicians can overrule the central bank to promote excessive credit expansion or to print too much of their own currency is a good place to invest. But the tendency of independent central banks to focus on price stability and ignore the regulatory/financial stability side is also seen as a dangerous formula.

In summary, recent crises left the impression that central banks paid no price for their collective failure and, in fact, that they emerged even more powerful than before. Moreover, populist sentiment has found that central banks are an attractive target to blame for any economic woes that might exist.

Worse still, independence is further endangered by the fact that the crisis pushed central banks into making choices with lasting distributional consequences. By making massive purchases of government bonds, quantitative easing has held both short- and long-term interest rates low for a very long time. While this may have helped to stimulate declining economies, it has done so by making rich owners of financial assets richer still. At the same time, poorer savers relying on bank deposits have been getting next to nothing.

Recent developments could be a watershed in the public approach to central banks, particularly in countries where the sensitivity to income distribution changes is high. The public may not tolerate leaving decisions with important distributional and fiscal consequences (such as those related to bank resolutions) to unelected bodies.

Central bankers in both developed and emerging market countries are keenly aware that the circumstances that defined CBI and brought it into prominence have changed in the postcrisis world. The broadening role of central banks — to include a responsibility for financial stability — necessitates some review of central bank governance and the relationship between central banks and governments. Nevertheless, many central banks continue to claim that their mandate remains relatively narrow and that independence is crucial although they are agreeable to strengthening transparency and accountability.

We begin our reexamination of CBI with a discussion of its origins, starting with an important essay by Milton Friedman (1962). We then discuss why the idea caught on in the 1980s to become an uncontested element of the economics canon. We then turn to the role of CBI in the years leading up to and after the financial crisis. CBI has had some positive effects in emerging markets. However, in developed economies with an increased emphasis on financial stability, thinking about CBI needs to be modified. Finally, we examine a case study, the independence of the U.S. Federal Reserve in the postwar period. We find that CBI is often more an aspiration than reality. Despite its legislated independence, the Fed has been repeatedly subject to political criticism from both the president and Congress, both of whom have attempted to influence policymaking.

Central Bank Independence: History of an Idea

The earliest mention of CBI that we have been able to identify is Milton Friedman’s 1962 essay titled “Should There Be an Independent Monetary Authority?” Friedman states that the central bank should be organized with the “objective of a monetary structure that is both stable and free from irresponsible government tinkering” (p. 224). He considered three organizing structures beginning with a commodity standard, which he dismissed because a fully automatic standard is not feasible in a complex banking system. Recall that Friedman was writing at a time when the Bretton Woods system tied currency values to the dollar and the dollar to gold.

Friedman (1962: 224) then turns to the idea of an independent central bank and notes that “so far as I know, these views have never been fully spelled out,” which leads us to suspect that the term CBI originates with Friedman. A central bank exists with “a kind of monetary constitution” that specifies its objectives and tools and establishes a bureaucracy to carry out the mandate. An independent central bank is one whose mandate — to achieve responsible control of monetary policy — is unaffected by anything the government might do. An independent central bank would “not be subject to direct control by the legislature” and presumably the executive as well. In Friedman’s argument, a completely private-sector central bank, like the prewar Bank of England, might have such characteristics, although Parliament could always revoke its charter, just as government could change the underlying monetary constitution of an independent central bank. Regarding independent central banks, Friedman (1962: 226–27) avers:

It seems to me highly dubious that the United States, or for that matter any other country, has in practice ever had an independent central bank in this fullest sense of the term. Even when central banks have supposedly been fully independent, they have exercised their independence only so long as there has been no real conflict between them and the rest of the government. Whenever there has been a serious conflict, as in time of war, between the interests of the fiscal authorities in raising funds and of the monetary authorities in maintaining convertibility into specie, the bank has almost invariably given way, rather than the fiscal authority.

Thus, the irony of Friedman’s ground-breaking effort to define CBI is that he rejects it. He finds it intolerable “in a democracy to have so much power concentrated in a body free from any kind of direct, effective political control” (p. 227). Friedman concludes that an independent central bank with “wide discretion to independent experts” (p. 239) is not the answer. Instead he prefers his third organizing structure — namely, legislation that specifies the rules for the conduct of monetary policy and restricts the central bank’s discretion.1 Rules maintain public control through the legislative process and insulate policy from the whims of politicians.

All in all, Friedman (1962) provided us with a durable definition of CBI — a monetary constitution that defines the objectives of the central bank and establishes an organizational structure that can use policy instruments to pursue those objectives independent of political interference. However, his definition includes a prescient warning that independence exists only so long as there is no real conflict between the central bank and the government. Nevertheless, the idea that a central bank should be able to exercise its policy discretion in pursuit of the goals stipulated by political authorities became a virtually uncontested tenet of modern policymaking.

The arguments in favor of an independent central bank began to crystallize in the 1980s after a decade or more of traumatic inflationary experience that put a spotlight on central bank policymaking and its failures.2

CBI came into prominence as a result of four disparate and largely simultaneous influences. First, the inflationary episodes of the 1970s led to a great deal of dissatisfaction with central banks, which were blamed for allowing it to happen. Central bank organization, governance, and policymaking needed to be rethought. Second, central banks were being established or reconstituted in many countries — in developed countries, newly independent countries, and later, in the transition countries. In every instance, the role and position of the central bank in government structures (Friedman’s monetary constitution) needed to be defined. Third, the rational expectations revolution in macroeconomics led to major changes in thinking about the role of monetary policy. Last, initial empirical investigations suggested that countries with more independent central banks seemed to experience less inflation. By 1990 or so, these four influences came together resulting in the universally held conclusion that central banks should be independent of political influence.

Inflationary Episodes of the 1970s

The inflationary experiences of the 1970s were economically disruptive, politically unappealing, and hard to eradicate. It was appealing to blame central banks and to suggest changes in their governance as a solution. For example, the Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker changed its policy procedures in 1979 in order to address the persistent high inflation. The difficulty in bringing inflation under control made central bank operations more than a matter of technical interest for the first time.

Policy Role of Central Banks