The Trump administration has proposed a new regulation that would greatly expand an old rule banning legal residence to immigrants deemed “likely to become a public charge” — that is, someone who the government has the responsibility to care for (USCIS 2018). The rule does not, nor could it, change eligibility for welfare programs for noncitizens in the United States. Instead, it requires applicants to prove that they are not likely, in the future, to become so dependent on welfare that they become a “public charge.” Therefore, the question regarding this regulation is not whether it is appropriate for noncitizens to become dependent on welfare, but whether the government will accurately predict their likelihood of doing so.

An accurate prediction would require the government to establish three things: (1) a workable definition of a public charge, (2) a threshold probability for considering someone “likely” to become one, and (3) a valid methodology for determining an applicant’s individual probability. The new regulation from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) fails on all counts. Its overbroad definition of a public charge will reject applicants who the government itself determines will primarily support themselves. In addition, it establishes no threshold probability for considering someone “likely” to become a public charge, and its methodology for determining someone’s likelihood is simply nonpredictive. Due to these inadequacies, DHS entirely fails to estimate how many people the rule will deny status.

If the department corrected the regulation, however, the regulation should deny few immigrants because few immigrants are likely to become public charges. The regulation primarily affects family-sponsored immigrants who already need a U.S. relative capable of supporting them at 125 percent of the poverty line, and very few applicants trying to receive permanent status to the United States are already using welfare, which census data indicate is one of the only certain predictors of future public benefits use. But the ambiguity and uncertainty in the regulation will certainly result in many applicants wrongly charged as “likely to become a public charge.” DHS should reissue its regulation to guarantee that the legal system is still a viable option for future immigrants.

DHS Defines “Public Charge” to Include Nearly Wholly Self-Sufficient Immigrants

Congress first enacted the statute on which the current public charge rule is based in the Immigration Act of 1882.1 The theory behind it was the same as for rules — enacted in the same legislation — that prevented the immigration of thieves and criminals. If the immigrant’s reason for relocating was to steal from or live off Americans, the government could protect its citizens from them. But this theory only extended to those who could not support themselves apart from public aid. If the government assisted people who would not be destitute without it, then that was the government’s choice — not a duty thrust upon it by the individual receiving aid.2

Thus, in its original understanding, “public charge” always had two components: substantial assistance from the government and inability to support oneself without it. In the 19th century, public charges were identified as “paupers” who lived in state- or locally funded almshouses — they were “wards of the state” for whom the government had near-total responsibility (Hirota 2017). The current DHS guidance accounts for both aspects of its historic meaning, defining “public charges” as those whose primary source of cash income (i.e., more than 50 percent) will come from means-tested government welfare programs (INS 1999).3

DHS’s new regulation disregards this twofold understanding. It states, “although a 50 percent threshold creates a bright line that may be useful for certain purposes, it is possible and likely probable that individuals below such threshold will lack self-sufficiency and be dependent on the public for support” (USCIS 2018: 51). But rather than lower the threshold to 40 percent, 30 percent, or even 20 percent of a person’s income, DHS plans to impose an absolute standard that ignores entirely the degree to which immigrants will support themselves.

The new definition will consider immigrants public charges if the government claims that they will likely use more than 15 percent of the poverty line — that is, $1,821 annually or $5 per day for a single individual. DHS determined Medicaid cannot be “monetized,” so it will treat enrollment for 12 months or more in any 36-month period as equal to the 15 percent figure. For example, someone who will make 150 percent of the poverty line ($18,210) and is projected to receive $1,821 ($5/day) in means-tested benefits would be deemed a “public charge,” even though they are 90 percent self-sufficient. Indeed, even people who the government itself projects will be 95 percent self-sufficient could easily be deemed a public charge.

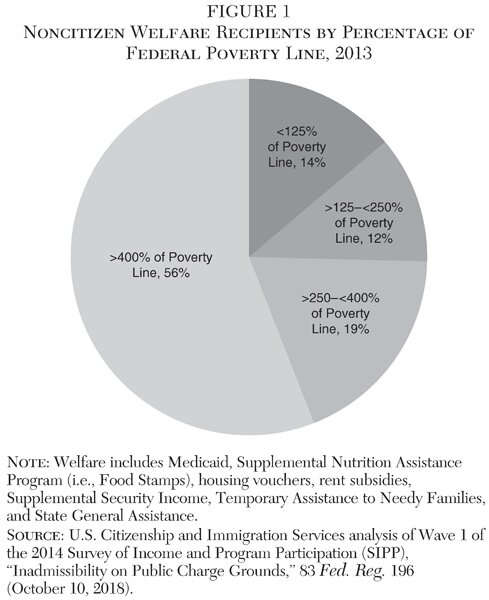

This situation is far from uncommon. According to DHS’s own estimates (see Figure 1), 56 percent of the noncitizens who received at least one means-tested welfare program in 2013 had household incomes greater than 400 percent of the poverty line, and 75 percent had incomes greater than 250 percent of the poverty line, while just 14 percent had incomes below 125 percent of the poverty line (USCIS 2018: 93). The distribution was essentially the same for U.S. citizens. Someone making 400 percent of the poverty line who received $5 per day in benefits would be at least 96 percent self-sufficient.

This illustrates not only how far removed America’s social safety net has become from serving people in desperate need but also why receipt of benefits alone is not sufficient evidence that recipients are unable to support themselves without the aid. Along the same lines, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) has found that only 20 percent of all welfare users received benefits in excess of 50 percent of their income from food stamps, Supplemental Security Income, or Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (Crouse and Macartney 2018: 8). Even perfectly implemented, DHS’s definition of public charge would keep out many immigrants who will be overwhelmingly self-sufficient.

This outcome fails to accord with the original meaning of the statute, but more importantly, it would harm the U.S. economy by excluding workers and taxpayers from legal residence in the country. In 2017, noncitizens receiving welfare paid $3.2 billion in taxes in all levels of government and had a combined income of $21.4 billion, according to the Census Bureau’s Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Current Population Survey.4 While not all noncitizen welfare users are contributing to the United States, many are, and DHS’s regulation fails to consider this fact.

DHS’s current guidance does not consider noncash welfare programs like Medicaid, housing, and food stamps (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program [SNAP]) as part of its projection of who will become “primarily dependent” on public support. While DHS’s new regulation appropriately takes these noncash programs into account when making public charge determinations, it cannot justify, economically or historically, adopting a public charge definition that completely disregards the degree to which individuals support themselves. DHS should maintain the current definition of “primarily dependent” — more than 50 percent of income — while incorporating noncash benefits. This definition is consistent with the historical understanding of the phrase and with the DHHS’s definition of “welfare dependency.” A more accurate definition would ensure that immigrants who will contribute to the U.S. economy can continue to enter and live legally in the United States.

DHS’s Poor Methodology for Predicting Likelihood of Becoming a Public Charge

Before the government can determine whether someone is “likely to become a public charge,” it must first clarify the meaning of “likely.” Yet, despite using it 295 times, DHS’s new regulation does not provide any definition for this key word. The current DHS public charge guidance also lacks one, but because it only factors in cash benefits, and the baseline probability of using cash benefits is so low (roughly 2 percent), denials are only issued in very extraordinary circumstances — essentially only when the person both has almost no income and is already receiving cash benefits (U.S. Department of State 2017: Table XX).5 Because DHS’s new regulation will look also at the likelihood of using noncash benefits, the baseline probability will rise more than tenfold, so the regulation now demands a much more precise estimation of the likelihood of dependency.

Without establishing a threshold of how likely it needs to be that someone will use more than its $5 per day in benefits level, DHS still leaves adjudicators without any real standard for who it should deny. Absent this, the department has not established what it considers a proper rate of wrongful denial (i.e., the share of denials for people who would not actually have become a public charge in the United States if admitted). If DHS intended to deny applications to those who have at least a 70 percent probability of becoming a public charge, then that would mean DHS would deem a wrongful denial rate of up to 30 percent acceptable. Alternatively, if it denied applications to those who have a 30 percent probability of becoming a public charge, then it would accept a wrongful denial rate of 70 percent.

When the Central Intelligence Agency studied various measures of uncertainty found in intelligence reports, it found that NATO military officers assigned wildly varying probabilities to the word “likely” — anything from 30 percent to 89 percent (Heuer 1999: 155). “Unlikely” (i.e., not likely) had a smaller but still very significant range from a 64 percent to 98 percent chance of not occurring. Of course, these results may reflect less the uncertainty in the meaning of the words than the uncertainty in the value of intelligence reports claiming events are likely or not likely to occur. Nonetheless, this study underscores the importance of clarifying the term.

Variation in the probability threshold will cause denials for individuals who should receive approvals and approvals for people who should receive denials, just as not defining the term “public charge” would. These wrongful denials are a major cost of the rule that the department has entirely failed to consider. The uncertainty by itself will impose costs on every U.S. employer or U.S. family member attempting to sponsor an employee or relative for legal residence, as the risk of applying will rise.

DHS should revise its regulation to define “likely,” establishing a uniform threshold probability of becoming a public charge that will trigger a denial. Merriam-Webster defines “likely” as “having a high probability of occurring or being true.” In normal parlance, “likely” indicates a likelihood significantly greater than a coin flip but less than a guarantee. A reasonable definition would take the midpoint between 50 percent and 100 percent, yielding a 75 percent threshold. The average NATO officer defined “likely” to mean about a 60 percent probability and “unlikely” (i.e., not likely) to mean about an 80 percent probability of not occurring. The midpoint between these two would result in a similar standard of 70 percent.

DHS’s Nonpredictive Model to Predict Likelihood of Becoming a Public Charge

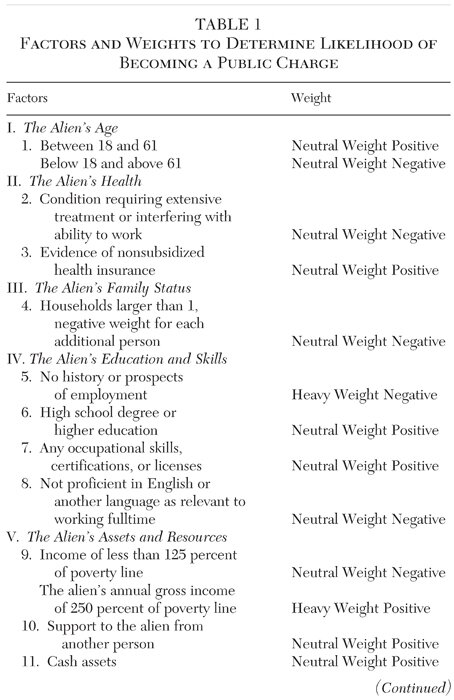

Once they establish precisely who adjudicators should target for exclusion, DHS needs a rigorous methodology to estimate the likelihood of becoming a public charge in particular cases. DHS will consider 8 primary factors and 17 secondary factors to predict future benefits use (Table 1). It plans to weight positively or negatively an applicant’s age, health, family size, financial status, education, length of stay, and U.S. sponsor’s affidavit of support. It categorizes factors as either having a “heavy” weight or a “neutral” weight. But because it never exactly quantifies the magnitude of these weights or how they operate in combination with other factors, adjudicators will decide weights on a case-by-case basis, and no applicant will know in advance whether they qualify or not.

Not only are the precise weights unspecified, DHS claims that the weights will actually change in further unspecified ways on a case-by-case basis. The regulation states, “The weight given to an individual factor not designated as carrying heavy weight would depend on the particular facts and circumstances of each case and the relationship of the factor to other factors in the analysis” (USCIS 2018: 66). This is like a points-based immigration system where neither the operators nor the applicants know the points before an application is adjudicated.

DHS provides two concrete examples of how it plans to implement this rule in practice (USCIS 2018: 103–4). These examples clearly show that adjudicators will not use statistical analysis. Instead, they will operate what amounts to a simple pro-con checklist, adding up the pros and cons and deciding which one “outweighs” the other. But this methodology will not yield valid results because it implicitly states that two negatives double the predictive power of any single negative, that three negatives triple it, that four negatives quadruple it, and so on. Not only is this obviously incorrect, some negative factors in DHS’s model have zero additional predictive power.

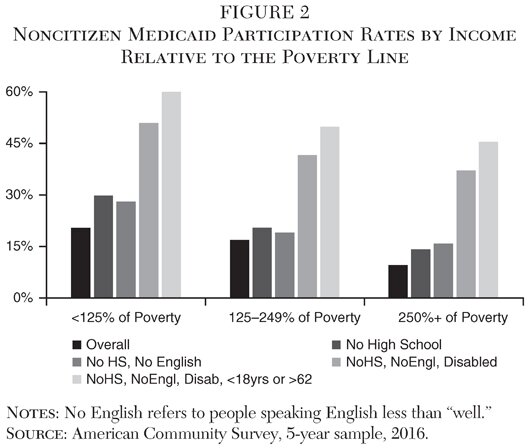

Figure 2 shows noncitizen participation rates in Medicaid — the largest means-tested benefit program — by income relative to the poverty line. DHS considers 250 percent of the poverty line one of the few “heavily weighted” positive factors, and a household income of 125 percent of the poverty line is a requirement. Each bar adds an additional negative factor. As it shows, not having a high school degree and not speaking English well or better are not more predictive together than they are separately. Yet, in DHS’s model, they effectively make the applicant twice as likely to be deemed a public charge. For those with incomes between 125 percent and 250 percent of the poverty line, each separately increases the probability of Medicaid use only slightly — less than 3 percentage points.

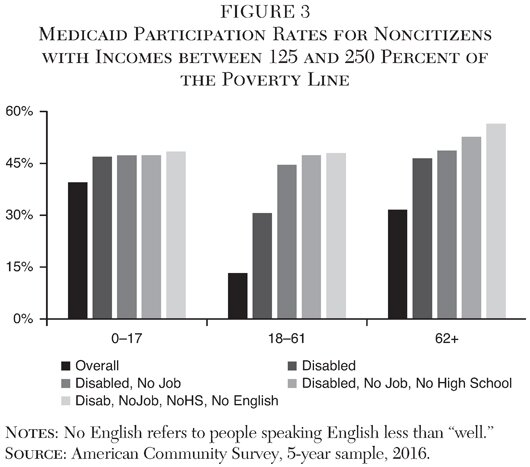

Figure 3 makes the same point but for people with the highest use rates, focusing only on those with incomes above 125 percent of the poverty line and below the heavily weighted 250 percent of the poverty line. It shows, for example, that while ages below 18 or over 61 predict greater use generally, those age groups do not predict significantly greater use for individuals who are disabled and lack jobs. DHS’s model is wrong to assume that age and disability operating together will always make someone far more likely to use benefits than those factors separately. Again, the marginal effect of not speaking English or not having a high school degree is quite minimal.

DHS has the information necessary — from government administrative data and census surveys — to build a statistically valid factor model that would accurately calculate the relative predictive power of each variable. It could make this model available to applicants online, letting them insert their information into the model and calculate their probabilities of becoming public charges. This type of online portal is something that Canada already uses for individuals wishing to immigrate through Canada’s points-based immigration system (Government of Canada 2017). Immigrants enter their ages, employment history, educational attainment, marital status, and English language ability, and the portal instantly calculates an immigration score, which determines eligibility for a visa.

Beyond reducing the number of wrongful approvals and denials, this option would allow immigrants to verify their eligibility before applying, which would reduce the number of unnecessary applications. It would also allow them to ascertain which characteristics or behaviors they would need to change to receive approvals, creating better results for both immigrants and the government. Even if the potential portal cannot estimate precisely the marginal effect of every factor due to data limitations, it could create a baseline probability estimate using factors for which data are available. This baseline would provide applicants and adjudicators with concrete valuations for known variables that each could then use to rationally consider the importance of the unquantified factors. The fact that DHS fails to make any serious attempt to estimate the marginal effect of its factors indicates that it has not fully thought through the implications of its rule.

DHS’s Rule Shouldn’t Affect Many Immigrants (Even If It Will)

Possibly due to these inadequacies, DHS also failed to estimate the most important effect of the rule: the number of immigrants and foreign travelers who the rule will deny the ability to come to the United States or who it will persuade not to apply due to a significant increase in the rate of denials. The only statement on this all-important point is that “DHS is not able to quantify the number of aliens who would possibly be denied admission based on a public charge determination pursuant to this proposed rule, but is qualitatively acknowledging this potential impact” (USCIS 2018: 147). DHS likely cannot quantify this figure because it cannot predict how adjudicators will implement its rule with any serious margin for error because it fails to define its key terms.

The public charge rule will theoretically affect almost all foreign visitors — tourists, students, and temporary workers — as well as three subsets of permanent residents: those sponsored by employers, those sponsored by family members, and diversity lottery winners. The statute exempts immigrants admitted for humanitarian reasons. In practice, however, most temporary foreign visitors will pass a public charge determination on the grounds that their visit will be brief, and they are already ineligible for most benefits during their stays in the United States. Moreover, of employer-sponsored immigrants, DHS states that it “believes that by virtue of their employment, such immigrants should have adequate income and resources to support themselves without resorting to seeking public benefits” (USCIS 2018: 10). Its single example of an applicant who passes a public charge determination is also an employer-sponsored immigrant.

As a practical matter then, the immigrants most likely to be excluded under this regulation rule will be diversity lottery winners and family-sponsored immigrants. Collectively these two groups accounted for 70 percent of legal immigration to the United States in FY 2017 — about 750,000 out of 800,000 of them are family-sponsored immigrants (in FY 2017) (DHS 2017: Table 6). This population can be divided into two groups: those who are already living in the United States in a temporary status and those who are entering the country from abroad. The public charge rule will affect each group differently.

Two-thirds of lottery winners and family-sponsored immigrants in FY 2017 entered the country for the first time from abroad (DHS 2017: Table 6). This means that they are guaranteed not to be on any public benefits when they apply for permanent residence. Moreover, because current law already requires a household income at or above 125 percent of the poverty line for family-sponsored immigrants, none are in poverty when they apply for green cards. Diversity lottery winners also need to show the capability of supporting themselves at a similar level of income (under the current public charge guidance).

Unfortunately, the available data are not precise enough to drill down on the exact population that the public charge rule affects. However, what data do exist indicate that few immigrants who are not currently on benefits and who have an income over 125 percent of the poverty line should be considered “likely” to become a public charge, even at the low $5 per day monetary threshold.

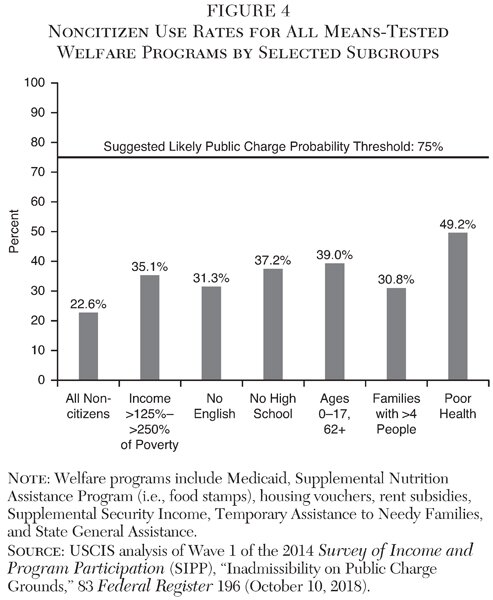

Figure 4 shows use rates of all means-tested welfare programs covered by the rule for different subpopulations of noncitizens. The rate of use of any means-tested public benefits in any amount for noncitizens with an income over 125 percent of the poverty line is just 35.1 percent, according to DHS’s own estimate.6 Moreover, as Figure 4 shows, DHS even failed to identify any subpopulation of noncitizens with use rates higher than 50 percent. Less than 40 percent of those above 61 or below 18 years of age used any welfare; as did just 30.8 percent of those in families with five or more people; 37.2 percent of noncitizen high school dropouts; 31.3 percent of noncitizen non-English speakers; and 49.2 percent of noncitizens with poor health (USCIS 2018: 49, 68, 73, 79, 83, 90).

These use rates would be lower if the $5 per day threshold was imposed, if certain exempt noncitizens — like humanitarian immigrants — were excluded, and if only households with an income of 125 percent of the poverty line were included (since they are the only ones eligible to apply for a green card under the regulation). Moreover, as Figures 2 and 3 make clear, multiple factors together do not significantly increase the predictive power of any single factor separately. People with poor health are more likely to use benefits but do not become significantly more likely to use benefits if they also cannot speak English, lack a high school degree, and are not in their prime working years. If DHS adopted a 70 percent probability threshold of becoming a public charge — as it should — it would have to conclude that almost all noncitizens who are not on welfare right now are not “likely” to be public charges.

However, for the third of immigrants applying for permanent residence who are already in the United States, the calculation is different because, while noncitizens without permanent residence are automatically ineligible for federal welfare, the public charge rule considers both federal and state benefits. Some noncitizens in temporary statuses or even illegal status can receive means-tested welfare in a few states — most importantly, state-funded Medicaid. As of September 2015, for example, 29 states and the District of Columbia have expanded Medicaid and the Children Health Insurance Program to noncitizen children and pregnant women who are in any lawful status (Broder, Moussavian, and Blazer 2015).

Because the census surveys do not record the specific types of status that a noncitizen has, however, it is not possible to identify how large this population might be. Given the lack of eligibility in many states, the high probability that many of those adjusting might have just arrived, and the higher education levels for recent family-sponsored and diversity lottery immigrants, this population is probably less than half as likely to be on welfare as other noncitizens. If they are half as likely, then at most 30,000 immigrants (2.7 percent of all immigrants) would be threatened by the public charge, if it were implemented with a 70 percent probability threshold and valid model for predicting the likelihood of future use.

However, the proposed regulation is also clear that noncash benefits received prior to its effective date would not be considered, meaning that anyone now receiving benefits would have time to get off if they intended to apply for permanent residence (USCIS 2018: 93). Some media reports indicate that this may already be happening in states like New York and California (Bottemiller-Evich 2018). While some organizations believe that this harms public health, the available evidence suggests that when noncitizen welfare was last restricted in 1996, immigrants compensated by working more and finding jobs with private health insurance, leading to no significant increases in poverty overall (Borjas 2016: 143–57). Overall, the evidence suggests that, if DHS implemented the regulation with a rigorous methodology, very few immigrants should be deemed a public charge.

Conclusion

The premise of the public charge rule is not wrong, and the Trump administration is correct that there is no good reason to arbitrarily exclude noncash benefits for consideration. The problem with its proposed redefinition is that it refuses to consider the economic and fiscal benefits of noncitizens who may receive more than $5 per day in benefits. This threshold would keep out many noncitizens who are up to 95 percent self-sufficient and contributing in significant ways to the U.S. economy. As importantly, the regulation never defines its key terms and so will lead to wildly variant outcomes depending on the adjudicator, causing denials for many people who should — even under the regulation’s restrictive definition — receive approvals.

The rule never calculates how many people it would keep out or what the fiscal losses to the economy would be of keeping them out. The recent report of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) on the fiscal and economic effects of immigration found that all immigrants in their working years contribute more in taxes than they receive in benefits, that the lifetime net present value for all immigrants who entered before the age of 25 is positive, and that the net present value of all immigrants with a high school degree or above is neutral or positive (NAS 2017: 331, 349). In 2015, nearly 90 percent of adult diversity lottery winners and family-sponsored immigrants had a high school degree or better, and almost half had a college degree or higher, and so are strongly fiscally positive (Bier 2018). The NAS also reported the academic consensus that immigrants — including unskilled immigrants — create a significant economic surplus for U.S.-born Americans (NAS 2017: 127–28).

The economic and fiscal benefits must enter the DHS calculation. DHS needs to rework its public charge rule to guarantee that only those immigrants who are likely to become public charges, and a significant burden on the government, are excluded. It should not finalize the regulation without first identifying how it will affect legal immigration and what burdens it will impose on legal immigrants, their sponsors, and the U.S. economy. This regulation is sloppy and ill-thought out, and the department should not implement it as written.

References

Bier, D. (2018) “Family & Diversity Immigrants Are Far Better Educated Than U.S.-Born Americans.” Cato at Liberty (January 25).

Borjas, G. (2016) “Does Welfare Reduce Poverty?” Research in Economics 70: 143–57.

Bottemiller-Evich, H. (2018) “Immigrants, Fearing Trump Crackdown, Drop Out of Nutrition Programs.” Politico (September 3).

Broder, T.; Moussavian, A.; and Blazer, J. (2015) “Overview of Immigrant Eligibility for Federal Programs.” Washington: National Immigration Law Center.

Crouse, G., and Macartney, S. (2018) “Welfare Indicators and Risk Factors: Seventeenth Report to Congress.” Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (May 4).

DHS (U.S. Department of Homeland Security) (2017) “Table 6. Persons Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident Status by Type and Major Class of Admission: Fiscal Years 2015 to 2017.” Available at www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/yearbook/2017/table6.

Government of Canada (2017) “Comprehensive Ranking System (CRS) Tool: Skilled Immigrants (Express Entry).” Available at www.cic.gc.ca/english/immigrate/skilled/crs-tool.asp.

Heuer, R. J. Jr. (1999) Psychology of Intelligence Analysis. Central Intelligence Agency. Available at www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/books-and-monographs/psychology-of-intelligence-analysis/PsychofIntelNew.pdf.

Hirota, H. (2017) Expelling the Poor. New York: Oxford University Press.

INS (Immigration and Naturalization Service) (1999) “Field Guidance on Deportability and Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds,” 64 Federal Register 28689 (May 26). Available at www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-1999-05-26/pdf/99-13202.pdf.

Locke, J. ([1693] 2004) “For a General Naturalisation.” In M. Goldie (ed.) Locke: Political Essays, 322–25. New York: Cambridge University Press.

NAS (National Academy of Sciences) (2017) “The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration.” Washington: National Academies Press. Available at https://doi.org/10.17226/23550.

USCIS (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services) (2018) “Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds,” 83 Federal Register 51114 (October 13). Available at www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2018-10-10/pdf/2018-21106.pdf.

U.S. Department of State (2017) “Table XX: Immigrant and Nonimmigrant Visa Ineligibilities.” Available at https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/visas/Statistics/AnnualReports/FY2017AnnualReport/FY17AnnualReport-TableXX.pdf.

1Immigration Act of 1882, 22 Stat 214 (August 3, 1882). Available at http://library.uwb.edu/Static/USimmigration/22%20stat%20214.pdf.

2An apt explanation of the traditional view can be found in John Locke’s essay, “For a General Naturalisation.” According to Locke ([1693] 2004: 325):

Another objection very apt to be made is that [immigration] will increase the number of the poor. If by poor are meant such as have nothing to maintain them but their hands, those who live by their labour are so far from being a burden that ’tis to them chiefly we owe our riches. If by poor are meant such as want relief and being idle themselves live upon the labour of others; if there be any such poor amongst us already who are able to work and do not, ’tis a shame to the government and a fault in our constitution and ought to be remedied, for whilst that is permitted we must ruin, whether we have many or few people.

3This includes Supplemental Security Income, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and State General Assistance.

4See www.census.gov/programs-surveys/saipe/guidance/model-input-data/cpsasec.html.

5A net of 1,221 applicants received a denial in FY 2017 (3,237 found ineligible; 2,016 overcame the finding).

6This is only the 2017 annual rate, but DHS admits that there is not significant annual turnover in the welfare-receiving population.