President Trump has delivered on his promise to shake up Washington, arguably nowhere more so than in the policy space of international trade. President Trump’s trade agenda has challenged more than seven decades of bipartisan policy commitment to seeking lower trade barriers at home and abroad through negotiated agreements.

While President Trump pays lip service to pursuing free trade and eliminating tariffs, his trade policies so far have been marked by higher U.S. duties on a range of products, from washing machines to steel. Under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, the administration has imposed duties on $250 billion of imports from China, with those duties set to escalate in 2019 absent an agreement with China. And under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, the president is threatening to impose a 25 percent duty on imported automobiles in the name of national security.

The Trump administration has renegotiated existing trade agreements with Canada, Mexico, and South Korea, but its modifications are as likely to restrict trade as expand it. One of the president’s first actions after assuming office was to withdraw the United States from the pending Trans-Pacific Partnership, which would have eliminated almost all duties with 11 trading partners around the Pacific Rim, including Japan.

President Trump has expressed skepticism about the benefits of trade for more than 30 years. In frequent statements, he asserts that the United States is “losing” hundreds of billions of dollars a year because of the annual deficit in merchandise trade. According to the recent book by Bob Woodward on the Trump presidency, the president told his staff, “Trade is bad” (Woodward 2018: 208). In March 2018, the president tweeted, “When a country (USA) is losing many billions of dollars on trade with virtually every country it does business with, trade wars are good, and easy to win” (Franck 2018).

This article will briefly state the case why, contrary to the president’s assertions, it has been in America’s economic interest to pursue free trade in the postwar era. It will then examine in more detail three main pillars of the Trump trade agenda — reducing the U.S. trade deficit, restricting steel imports, and confronting China with escalating tariffs. And it will conclude with a brief plan to return the United States to the previous path of seeking lower trade barriers through cooperative agreements.

The Blessings of Freer Trade in the Postwar Era

As a nation the United States has been reaping the benefits of freer trade for more than 70 years. For millions of American households, lower trade barriers in the United States have delivered lower prices, more variety, and better quality in the goods and services people buy every day. Because of the increased competition from international trade, Americans can buy more affordable footwear, clothing, electronics, household goods, and food, including fresh fruit in the winter. Lower prices are especially important for lower-income Americans, who spend a higher share of their budget on tradable goods (Furman, Russ, and Shambaugh 2017). For millions of workers, the lower prices from trade translate into higher real wages.

U.S. producers also benefit as importers. Half of U.S. annual imports are not for consumption but for production — raw materials, industrial supplies, capital machinery (U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis 2018: Exhibit 6). U.S. producers depend on access to globally priced inputs to stay competitive. And more obviously, U.S. firms benefit as exporters to world markets. Freer trade opens opportunities to sell to the 95 percent of the world’s people and three-quarters of the world’s spending power that is outside the United States (World Bank 2018). In 2017, Americans exported $2.4 trillion worth of goods and services to people in other countries (U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis 2018: Exhibit 1). American firms sell another $6.0 trillion in goods and services through their affiliates located in foreign countries, with 94 percent of those sales outside the United States (Jennings 2017).

Trade is not about more jobs or fewer jobs. Robust trade is clearly compatible with low unemployment. Through 2018, the U.S. economy has enjoyed the lowest unemployment rate in almost 50 years at a time of record imports. Trade is about better jobs — about specializing in what we do best and doing more of it, while importing what people in other countries are better at making.

As President Trump justifiably touted in the recent mid-year election campaign, the U.S. economy is doing well at the halfway mark of his first term, and trade is an important part of the story. And yet the president also routinely complains about the supposedly damaging effects that trade and trade agreements have imposed on the American economy. His complaints focus on three areas — the persistent U.S. goods deficit, imported steel, and China.

President Trump’s Unbalanced View of the Trade Deficit

On the balance of trade, President Trump says that Americans are “losing” $800 billion a year in goods trade. This is the difference between what Americans spend on imported goods and what foreigners spend on U.S. exported goods. To President Trump, the deficit represents money stolen from Americans, the result of bad trade deals that we must change or scrap. But the trade balance is not a scorecard for trade. Trade is a win-win for Americans, the sum total of millions of mutually beneficial transactions. The trade deficit is not the result of trade policy, but of underlying levels of savings and investment in the economy. In the United States, we save less than what is invested, which means a net inflow of foreign capital, resulting in an overall deficit in the current account.

The $800 billion deficit in goods is not a loss, but a gain of useful goods that make our lives better. Almost every American household runs a trade deficit with the neighborhood grocery store. Complaining about the “lost” $800 billion from the U.S. trade deficit is like a shopper grumbling about the $150 he lost at the checkout counter while heading to his car with a cart bulging with groceries.

President Trump also ignores the fact that trade is not just about goods. More than one-third of U.S. exports are services (U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis 2018: Exhibit 1). And Americans also trade in assets — stocks, bonds, bank deposits, real estate — representing the flow of capital. The flip side of the U.S. trade deficit is a capital surplus. The United States remains a magnet for international investment, both direct investment and, even more so, portfolio investment, especially U.S. Treasury bills. It is contradictory to complain about the trade deficit while at the same time to welcome the inflow of foreign investment. If we spend $1 billion on imported cars, and foreigners use that money to buy $1 billion of exported soybeans, we have balanced trade. But if they use the $1 billion to build an automobile factory in the United States, employing thousands of Americans in good paying, sustainable jobs, we have a $1 billion capital surplus, and a $1 billion trade deficit. Why is the first scenario good and the second bad? Why isn’t the “capital surplus” scenario just as good, or better, than the “balanced trade” scenario?

In fact, U.S. trade in the broadest sense is already perfectly balanced. In recent years, about $4 trillion flows out of the United States each year to purchase foreign goods, services, and assets, and $4 trillion flows in from abroad each year to buy American goods, services, and assets.

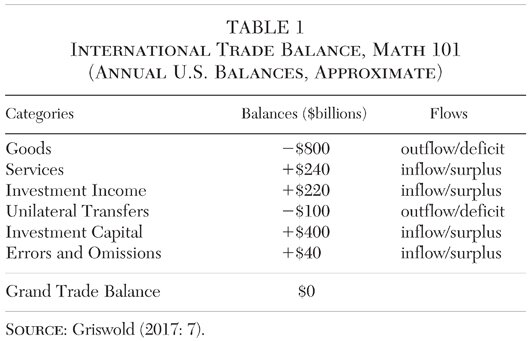

Consider Table 1 summarizing the U.S. balance of trade in recent years. It’s true, as the president says, that a net $800 billion or so flows out of the United States each year in the form of the goods deficit. But those dollars immediately flow back to the United States through different channels. About $240 billion flows back in the form of the U.S. surplus in services trade. Another $220 billion flows back in surplus earnings on foreign investment — profits, dividends, and interest earned on foreign assets. An even larger $400 billion flows back in the form of a capital surplus — the net inflow of investment into factories, real estate, bank deposits, stocks, bonds, and Treasury bills. After factoring in the smaller categories of unilateral transfers and a statistical adjustment for errors and omissions, the grand international trade balance each year for the United States is a big fat zero (Griswold 2017: 7). We don’t lose a dollar in international trade. What we gain is a more efficient, dynamic, and prosperous economy.

One great irony of Trump’s trade policy is that its broader economic policies are contributing directly to expanding trade deficits now and in the years ahead. The investment and growth spurred by the administration’s deregulation efforts and the tax reform bill the president signed in December 2017 will mean more demand for imports by households and producers. The looming $1 trillion annual deficits in the federal budget mean more foreign investment in Treasury bills, with the federal government in effect out-competing U.S. exporters to attract the limited dollars available in foreign exchange markets. The bottom line for Americans should be to not worry about the trade deficit. It distracts us from more important policy goals and leads us to enact bad policies, such as tariffs.

The Spreading Damage of Steel Tariffs

Starting in March 2018, the Trump administration began to impose 25 percent duties on imported steel in the name of “national security.” In June, the duties were extended to the European Union, Canada, and Mexico. As a direct result, steel prices in late 2018 were up 38 percent from a year earlier (Layne 2018). Ironically, the duties have not been an obvious boon to the domestic steel industry. The higher prices have predictably dampened the quantity of steel demanded in the domestic market, and the share prices of major U.S. steel producers such as Nucor have underperformed the overall stock market since the duties were imposed (Perry 2018).

The steel duties are based on a false premise. Steel imports pose no threat to the steel industry or our national security. The United States produces about 80 million tons of steel a year, making it the world’s fourth largest producer (World Steel Association 2018). The U.S. Commerce Department’s own Section 232 report on steel and national security found that, “In 2017, [the Department of Defense] estimates for U.S. steel needs is now calculated to be 3 percent of U.S. steel production” (U.S. Department of Commerce 2018a: Appendix H, 4). There is no danger of the United States running short of steel capacity for the U.S. military in any conceivable national security scenario.

The long-term decline in employment in the U.S. steel industry is not because of imports or trade deals, but because of fundamental and positive shifts in the U.S. economy. Consolidation in the steel industry began decades ago. On September 19, 1977, in Youngstown, Ohio, on a day still remembered there as “Black Monday,” the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company laid off 5,000 well-paid, unionized steelworkers (Boney 2017). That occurred more than 40 years ago, long before anyone even dreamed about the North American Free Trade Agreement or China’s entry into the World Trade Organization.

Two driving forces in the steel sector led to the layoffs that day in Youngstown and to declining steel employment since then, neither of them directly connected to trade. Since the 1970s, per capita consumption of steel in the United States has dropped by almost half, from an average of 1,415 pounds per year (World Steel Association 1982: 38–39) to 758 pounds per year in 2012–16 (World Steel Association 2017: 83–84). This is a natural development in an advanced economy where technology and the service sector play an increasingly important role. Over that same period, productivity in the steel industry has soared. In the early 1980s, it required an average of 10 man hours of labor to produce a ton of steel; today it requires less than 2 hours (American Iron and Steel Institute 2018: 4). It is simple math that if fewer units of steel are demanded, and it requires fewer inputs of labor to produce each unit, then the total demand for labor in the industry will go down. Tariffs on imported steel will not bring those jobs back to Youngstown or to the steel industry as a whole. In fact, the higher prices imposed by the tariffs will keep less efficient producers in business while reducing the long-term demand for steel by encouraging the use of substitutes.

Higher domestic steel prices have inflicted immediate and significant damage on consumers and downstream industries. While those higher prices may confer temporary benefits for the 140,000 workers in the steel industry, they are bad news for the 6 million workers in steel-using industries (Pearson 2016). The largest consumers of domestic steel are the construction industry and automobile manufacturers. The news media provide a daily stream of reports on U.S. companies, large and small, that are suffering from the artificially imposed higher steel prices. The nation’s largest nail manufacturer, Mid-Continental Nail Co. in Missouri, has laid off a third of its 500 workers and is facing closure without relief (Lobosco 2018). Hundreds of U.S. companies have filed thousands of exemption requests with the U.S. Commerce Department claiming the steel tariffs are preventing them from buying the steel they need to maintain production (McDaniel 2018).

U.S. steel tariffs have provoked retaliation from other countries. In March 2018, President Trump’s trade adviser Peter Navarro confidently predicted, “I don’t believe any country is going to retaliate for the simple reason that we are the most lucrative and biggest market in the world” (Stelzer 2018). That assumption has proven to be spectacularly wrong. In response to the steel tariffs, major U.S. trading partners have imposed selective duties on billions of dollars of U.S. exports. One iconic U.S. company caught in the crossfire is Harley-Davidson, the motorcycle maker based in Wisconsin. Harley has been squeezed on the production side by higher steel prices, while its exports to Europe now face retaliatory tariffs. In response, the company plans to shift production offshore, not to import back to the United States, but to meet demand in other countries (Gibson 2018).

The Trump administration’s steel tariffs are a self-inflicted wound on the U.S. economy. The administration first declares a commodity to be vital to the economy and national security and then takes steps to make that commodity more scarce and expensive. Imagine if a foreign power tried to restrict U.S. access to international steel supplies with a blockade. Americans would rightly consider it an act of war. Yet this is just what the administration is doing to its own country. It brings to mind the observation of the 19th century American economist Henry George that, “What protection teaches us, is to do to ourselves in time of peace what enemies seek to do to us in time of war” (George [1886] 1992: 47).

A Needless, Damaging Trade War with China

A third priority of the Trump administration’s trade agenda is China. The administration’s trade team shares the assumption of many critics of China that is was a mistake to grant China permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) in 2000 as a condition of its joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. The critics tend to exaggerate the impact of that event. The United States had granted China conditional NTR for two decades before its accession, starting in 1980, which gave imports from China the same duty treatment that the United States grants to almost all other nations in the world. China’s membership in the WTO did not require the United States to alter a single tariff on imports from China, but it did require the U.S. Congress forgo its annual vote on granting NTR access to China.

As part of its accession agreement, China reduced the average tariff rate on imports from the United States from 25 percent before its entry to 7 percent after implementation (U.S. Trade Representative 2015: 42). Between 2001 and 2017, the total value of imports of goods and services from China increased five-fold, while the total value of U.S. exports to China increased more than seven-fold. That means that since China’s accession to the WTO, imports from China have grown at an annual compounded rate of 10 percent, while U.S. exports to China have grown at a rate of 14 percent (U.S. Department of Commerce 2018b; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis 2018).

President Trump routinely complains about the bilateral goods deficit with China, but this number is essentially meaningless. Imports from China contain a huge share of value added from other countries, including the United States. When the components of imports from China are assigned to the country where the value was actually added, the bilateral trade deficit drops by more than one-third (Hoffman and Lundh 2018). Goods that used to come directly to the United States from those other trading partners are now rerouted through China for final assembly. Duties on imports from China will more likely result in the targeted goods being imported from other foreign suppliers rather than from domestic U.S. producers.

Americans have a lot to lose in a trade war with China. China is the fourth largest market in the world for U.S. goods and services exports, behind only the European Union, Canada, and Mexico (U.S. Census Bureau 2018: Exhibit 20). U.S. multinational firms sell another $350 billion in goods and services through their affiliates in China, more than 95 percent sold in China or third countries (Jennings 2017: Table 7.2). China is also an important source of investment capital for the United States. The Chinese purchase of U.S. Treasury bills has helped in the past two decades to keep long-term U.S. interest rates lower than they would be otherwise, saving Americans billions of dollars a year in lower interest payments on their mortgages and the national debt.

President Trump and his trade advisers claim that China’s “economic aggression” threatens America’s long-term security and prosperity. They exaggerate the impact of China’s industrial policies and its violation of intellectual property. No advocate of the free market would defend China’s interventionist policies, but the impact on the United States needs to be considered along with the huge benefits. China is in the middle of the pack in terms of respecting global rules on intellectual property. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce (2018) ranks China 25th out of 50 major trading nations in its protection of intellectual property. According to Nicholas Lardy (2018) of the Peterson Institute, China ranks fourth in the world in payments of licensing fees and royalties for the use of foreign technology. Those payments reached $30 billion in 2017, a four-fold increase from a decade ago.

The U.S. government has real differences with China, but it would be better to work with trading partners to exert collective pressure rather than jeopardize a mutually beneficial trade and investment relationship with a tariff war. A much more promising approach would be to join with our G7 partners in Japan, Canada, and the European Union in a joint effort to bring pressure on China through the World Trade Organization. Unfortunately, the Trump administration seems to be as eager to foment trade conflict with our strategic friends as it does with our rivals.

The Trump administration’s escalating tariff war is inflicting more damage on the U.S. economy than anything the Chinese government has done. Prices are going up on a wide range of consumer goods, with low-income households suffering the most. Walmart, the nation’s largest retailer, has warned it will be forced to raise prices on a large number of products imported from China (Mourdoukoutas 2018). The cleanup from Hurricane Florence is being made more costly because of the tariffs. On top of the duties on lumber, steel and aluminum that the Trump administration has already imposed, the new China tariffs will raise the cost on such products as countertops, furniture, and gypsum, a key ingredient in drywall. Builders estimate that construction costs could be 20 to 30 percent higher than they would have been without these tariffs (Schwartz 2018).

The Trump administration’s fears about China betray a fundamental lack of confidence in the American model of a free and open economy. The White House trade team has yet to receive the memo that central planning lost its Cold War confrontation with the more open free-market democracies of the West. China’s government can draw up any plan it wants about dominating key industries, but central planning will not make it a reality.

Thirty years ago, the focus of U.S. trade skeptics (including a certain prominent New York real estate developer named Trump) was Japan. Their view at the time was that the Japanese government also had a plan to take over the commanding heights of the global economy — through unfair trade practices, a bulging bilateral trade surplus with the United States, and an industrial policy orchestrated by its mighty Ministry of International Trade and Industry. Yet that model proved to be far less effective and threatening than feared.

Our confidence should be in the free market, not in central planning. America remains the world’s technological and economic leader because we also remain, for now, the most open, competitive and dynamic major economy in the world. For all its challenges, the United States retains the advantage of flexible and open markets, relative openness to immigration, a world-class technology sector, and a stable democratic system. The greatest threat to our standard of living is not the policies pursued by a foreign power, but those that our own government could impose on us in a misguided and misinformed response to an exaggerated threat from abroad.

For all its growth in the past three decades, China is not a viable or attractive alternative to the democratic capitalist model. China’s per capita gross domestic product (on a purchasing power parity basis) was $16,700 in 2017, still only one third the level of Taiwan’s $50,300, and an even smaller share of the United States’s level of $59,500 (U.S. Central Intelligence Agency 2018). China’s economy faces long-term headwinds that no central planning can fix. Its one child policy has led to a plunging birthrate, a shrinking workforce, and a rapidly aging population, imposing enormous costs on the Chinese economy in the coming decades. Adding to China’s burden are its inefficient state-owned enterprises and a financial system burdened with bad debt. The last thing U.S. policymakers should do is make the U.S. system more like theirs.

The Path to Recovering U.S. Trade Leadership

The right response by the U.S. government should be to reassert America’s commitment to a postwar trading system based on nondiscriminatory tariffs, dispute settlement through the WTO, and lower trade barriers at home and abroad through either unilateral liberalization or reciprocal trade agreements.

Specifically, the United States should repeal the misguided and damaging duties that have been imposed on imported steel, aluminum, and other products, as well as the Section 301 duties imposed on imports from China. The administration should abandon its threats to seek higher duties on imported motor vehicles through an abuse of the Section 232 trade law. Such duties would inflict damage on the U.S. economy that would be multiples greater than the damage already caused by the steel tariffs.

To advance trade liberalization, the administration should pursue a free-trade agreement with the United Kingdom after its formal exit from the European Union in March 2019. This would deepen ties to a major trading partner and the world’s fifth largest economy (Griswold 2018; Ikenson, Lester, and Hannan 2018). The United States should also seek to rejoin the reconfigured Trans-Pacific Partnership, which will soon go fully into effect with the other 11 partner nations but not the United States.

Finally, Congress must reassert control of U.S. trade policy. Article 1, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution gives Congress exclusive power to collect duties and “to regulate commerce with foreign nations.” Congress should repeal or revise its existing trade statutes to guard against the kind of manifest abuse this administration has exercised. U.S. trade policy was not meant to be made by a small, insulated group inside the White House, at the expense of millions of American families and our long-term national interest.

References

American Iron and Steel Institute (2018) Profile 2018: Strength for Our Future. Washington: American Iron and Steel Institute.

Boney, S. (2017) “40 Years Later, Effects of Black Monday Still Apparent in Youngstown.” WKBN News (September 16).

Franck, T. (2018) “Trump Doubles Down: ‘Trade Wars Are Good, and Easy to Win.’” CNBC.com (March 2).

Furman, J.; Russ, K.; and Shambaugh, J. (2017) “US Tariffs Are an Arbitrary and Regressive Tax.” Vox (January 12).

George, H. ([1886] 1992) Protection or Free Trade. New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation.

Gibson, K. (2018) “Harley-Davidson’s U.S. Sales Skid in Quarter That Included Trump Spat.” CBS News (October 23).

Griswold, D. (2017) “Plumbing America’s Balance of Trade.” Mercatus Center Research Paper, George Mason University (March).

__________ (2018) “Leading the Way with a US-UK Free Trade Agreement.” Mercatus Center Research Paper, George Mason University (October 30).

Hoffman, D., and Lundh, E. (2018) “‘Huge’ Trade Deficits Are Smaller Than You Think.” Bloomberg (March 18).

Ikenson, D. J.; Lester, S.; and Hannan, D. (2018) “The Ideal U.S.-U.K. Free Trade Agreement: A Free Trader’s Perspective.” Cato Institute White Paper (September 18).

Jennings, D. (2017) “Activities of U.S. Multinational Enterprises in 2015,” Table 7.2. Selected Statistics for Majority-Owned Foreign Affiliates by Country of Affiliate, 2015. Survey of Current Business (December 2017). Washington: U.S. Department of Commerce.

Lardy, N. (2018) “China: Forced Technology Transfer and Theft?” Peterson Institute for International Economics (April 20).

Layne, R. (2018) “Trump’s Tariffs Have U.S. Companies Cutting Their Forecasts.” CBSNews.com (November 2).

Lobosco, K. (2018) “Largest U.S. Nail Manufacturer Clings to Life under Steel Tariffs.” CNN.com (September 4).

McDaniel, C. (2018) “Trump Team Wildly Underestimated the Costs of Tariffs.” The Hill (September 24).

Mourdoukoutas, P. (2018) “China Tariffs Could Spoil Christmas Shopping for Low-Income Americans and Walmart.” Forbes.com (October 20).

Pearson, D. (2016) “Global Steel Overcapacity: Trade Remedy ‘Cure’ Is Worse than the ‘Disease.’” Cato Institute Free Trade Bulletin No. 66 (April 11).

Perry, M. (2018) “Trump’s Tariffs Are Backfiring Even on Industries That Were Supposed to Benefit from Trade Protectionism.” Carpe Diem Blog, American Enterprise Institute (October 28).

Schwartz, N. (2018) “Tariffs to Raise Cost of Rebuilding after Hurricane Florence.” New York Times (September 21).

Stelzer, I. (2018) “Is the Trump Economy Sustainable?” Weekly Standard (August 4).

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (2018) “U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services.” Available at www.bea.gov/data/intl-trade-investment/international-trade-goods-and-services.

U.S. Census Bureau (2018) “U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services (FT900), U.S. Trade in Goods and Services by Selected Countries and Areas-BOP Basis.” Available at www.census.gov/foreign-trade/Press-Release/current_press_release/index.html.

U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (2018) CIA World Factbook, “Country Comparison: GDP per Capita (PPP).” Available at www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2004rank.html.

U.S. Chamber of Commerce (2018) U.S. Chamber International IP Index, 6th ed. (February). Available at www.uschamber.com/press-release/us-chamber-releases-sixth-annual-international-ip-index.

U.S. Department of Commerce (2018a) “The Effects of Imports of Steel on the National Security: An Investigation Conducted under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1961, as Amended.” Bureau of Industry and Security and Office of Technology Evaluation (January 11).

__________ (2018b) “Country and Product Trade Data, U.S. Trade in Goods by Country.” Available at www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/index.html.

U.S. Trade Representative (2015) “2015 Report to Congress on China’s WTO Compliance.” (December) Available at ustr.gov/sites/default/files/2015-Report-to-Congress-China-WTO-Compliance.pdf.

Woodward, B. (2018) Fear: Trump in the White House. New York: Simon & Schuster.

World Bank (2018) “World Bank Open Data.” Available at https://data.worldbank.org.

World Steel Association (1982) Steel Statistical Yearkbook 1982, Table 14, Apparent Steel Consumption per Head, pp. 38–39. Brussels: World Steel Association.

__________ (2017) Steel Statistical Yearkbook 2017, Table 40, Apparent Steel Use per Capita, pp. 83–84. Brussels: World Steel Association.

__________ (2018) “World Crude Steel Output Increases by 5.3% in 2017.” (January 24). Available at https://www.worldsteel.org/media-centre/press-releases/2018/World-crude-steel-output-increases-by-5.3–in-2017.html.