In many countries, the rising cost of publicly funded health care, retirement, and other welfare programs is forecast to put increasing pressure on government budgets. As a result, many governments are seeking to reform their welfare states so that costs to the taxpayer can be reduced, quality of outcomes increased, and the plight of low- and middle-income earners improved. Regrettably, there are currently at least three problems with much of the debate about reform of the welfare state.

First, disagreements are often focused around two opposing ideological viewpoints. One side is demanding more welfare spending and higher taxes, whereas the other is arguing for less welfare spending and lower taxes. Second, even when economists and others propose a welfare reform that appears promising in theory, designing the transition so that it is politically feasible is often overlooked. Third, the debates are typically quite narrow. They seldom focus on a comprehensive reform that would rewrite the rules governing the welfare and tax system as a whole, with the aim of making them work more fairly and efficiently.

This article shows how a country can move from a publicly funded welfare system to one that relies largely on private funding coming from compulsory savings accounts. The reforms we propose are designed to overcome the problems outlined above. We use New Zealand, a nation with which we are familiar, as a case study, although the comprehensive reform we recommend can be adapted elsewhere.

How does it work? Taxes currently paid on personal earnings up to $50,000 for single taxpayers go directly into the compulsory savings accounts.1 A drop in the corporate tax rate and the removal of other government-imposed employee costs help employers fund contributions. These changes allow for privately funded welfare payments to substitute for public ones. Total spending levels can be maintained across most welfare categories, and transparent pricing of health care services and out-of-work cover can be introduced.

Provided that special privileges in the form of subsidies to businesses (i.e., corporate welfare) and grants to affluent families are discontinued, tax cuts can be made sufficiently deep to allow people to establish significant savings balances, while largely retaining pre-reform disposable incomes.

Even after our proposed tax cuts, the government retains sufficient revenues to act as an insurer of last resort, helping to pay for those individuals who cannot meet all of their own welfare expenses out of their savings accounts (e.g., the chronically ill).

Our “savings not taxes” reform offers the scope for efficiency gains, particularly in health care. While we believe these gains are plausible, they have not been factored into our estimated budgetary forecasts, which as a consequence probably understate the benefits of our reforms. One example of the scale of the possible gains comes from the experience of the pro-market reforms in New Zealand in the 1980s and 1990s (see Evans et al. 1996). Another example is Singapore, which uses compulsory savings accounts and currently spends just 4.8 percent of GDP on health and long-term care, compared with 17.2 percent in the United States and 9.5 percent in New Zealand, and yet maintains one of the highest quality services in the world.

More broadly, our “savings not taxation” reform is aimed at changing beliefs away from a culture of dependency to one of independence, whereby lower-income earners are given the opportunity to build up their own capital via tax relief and employer contributions, and can then choose from among a range of affordable services.

Background: The Long-Run Viability of Publicly Funded Welfare

Large publicly funded welfare states are under threat. The dependency ratio, which is the proportion of elderly to younger, economically active workers, is expected to rise all over the world. Severe pressures will be brought to bear on pensions and, in particular, public health systems.

The ratio of public health and long-term care expenditure to GDP has already been rising steadily for several decades. The latest projections for the next several decades highlight the growing pressures. In the OECD’s “cost-pressure” scenario, average health and long-term care public expenditures are projected to almost double, reaching approximately 14 percent of GDP by 2060. Furthermore, public pension spending is forecast to grow from 9.5 percent of GDP in 2015 to 11.7 percent of GDP in 2050 across OECD countries (OECD 2013).

Having recognized the welfare state problems that face almost every developed nation, we must ask ourselves, “What can we do about it?”

First, we need to quantify the problem in a way that politicians, economists, the news media, and others cannot ignore. One way is to forecast health and pensions spending as a fraction of GDP over the next several decades. As noted above, the OECD (2013) reports strongly rising trends. Another way is to measure the “fiscal gap,” which is the present value of projected future government expenditures net of the present value of future taxes. Using this approach, Kotlikoff (2013) argues that the true U.S. fiscal debt is not the $US 13 trillion usually reported by the government, but is instead over $US 200 trillion.

Alternatively, one can bring the gross value of unfunded liabilities into the government accounts using accrual accounting principles.2 New Zealand had a 2015 fiscal deficit of 4 percent of GDP once an allowance was made for the increased accrued cost of health and pensions spending, which is due to the higher number of retirees at the end of the year compared with the beginning. That deficit stands in contrast to the cash surplus usually reported.

Second, we need to set aside traditional myths and return to fundamentals. This involves adopting several principles related to successful structural change (Douglas 1989):

• Only medium-term quality decisions, and not quick-fix solutions, make a difference. We must get the incentives and framework right to help ensure everyone acts more effectively.

• Decisions relating to welfare should identify and exploit economic and social linkages, so that every action will improve the working of the system as a whole. We should not treat every problem separately, as most countries do.

• Only large-scale reform packages provide the flexibility needed to demonstrate that any losses suffered by a group of people from one policy would be offset by gains for the same group in some other area.

Third, any fundamental reform of the welfare system would need to be based on improving opportunity, incentives, and choice if people are to accept widespread changes of the kind implemented in, for example, Singapore.

Singapore provides universal health care coverage at a lower cost than any other high-income nation. By most measures, such as infant mortality and life expectancy, outcomes are excellent. The cornerstone of the system is a compulsory medical savings account called MediSave. It is based on the idea that people should be helped to save for their own health care expenses. Individuals and their employers are required to contribute a specified portion of wages into each individual’s account. The accounts are held within the government-managed Central Provident Fund.

Although MediSave funds belong to the contributing worker, the government has guidelines as to how the money can be spent. Its aim is to balance affordable health care against overconsumption and prevent the premature depletion of funds. For large bills that could otherwise drain one’s MediSave funds, insurance schemes are available. The government offers a low-cost one called MediShield, under which individuals are automatically insured unless they choose to opt out.

Another component of Singapore’s system is MediFund, which is a government safety net. It is a multibillion dollar endowment fund designed to help the lowest-income earners receive a level of care that they otherwise could not afford, even in the most highly subsidized public hospital wards.

Haseltine (2013: 51) believes that the MediSave account plays a crucial role in keeping high-quality health care affordable because,

when people have to spend their own money, as the Singapore system requires, they tend to be more economical in the solutions they pursue for their medical problems. In contrast, in countries with third-party reimbursement systems … since someone else is paying—government programs, insurance companies—there is little incentive to be prudent.

Our proposed reform includes the establishment of individual mandatory health savings accounts (HSAs), similar to the Singapore model.

Aside from the challenges that stem from maintaining a quality health care system, a large literature has discussed the challenges faced by public pension schemes due to population aging. When the number of recipients rises, governments often reduce the per capita generosity of publicly funded programs to help fit their budget constraints.

To prepare for this future, one might expect private savings rates to rise in nations with large publicly funded systems. However, this trend does not appear to be happening. Various ways of increasing savings in these nations are often debated (Shiller 2004). For example, some commentators advocate changes to the tax system to encourage savings. Others argue that there is a self-control problem biasing people toward overconsumption. In this case, automatically enrolling people in a savings plan, whereby one is joined up unless specifically electing to opt out, may be a solution. An example is New Zealand’s Kiwi Saver scheme. Another response is to introduce compulsory retirement savings accounts, which are a feature of Singapore’s system. While our proposed reform also introduces these types of accounts, it differs from the Singapore model by retaining the New Zealand state pension.

Last, we continue New Zealand’s tradition of providing protection for the out of work. However, changes are made to the existing system by establishing compulsory risk cover accounts to help pay expenses should one be unemployed, regardless of cause. In this sense, we depart from Singapore’s zero unemployment benefit policy.

Designing the Shift to a “Savings Not Taxes” Welfare System

We now address the question of how to design a policy reform that allows a welfare system heavily reliant on public funding to be changed into one that increasingly draws on private funding. New Zealand is used as a case study, although we also discuss how the reform could be applied to the United States. A distinguishing feature of our new regime is that it proposes a unified approach to the funding of health care, retirement, and risk cover through the establishment of a set of compulsory savings accounts. In getting the framework right, we needed to adjust the tax system so that most New Zealanders of working age could provide for themselves.

Tax Reform

With respect to personal income tax (PIT) the rate is presently set at 10.5 percent for incomes from $0 to $14,000 and 17.5 percent for those between $14,000 and $48,000. Tax rates rise to 30 percent for incomes between $48,000 and $70,000. The top rate of PIT is 33 percent for incomes over $70,000.

Under the new regime, PIT falls to zero for single taxpayers (i.e., a single person or couple with two incomes) earning less than $50,000. It becomes 17.5 percent for incomes between $50,000 and $70,000, and 23 percent beyond $70,000. For single-income families with dependent children, PIT rates fall to zero for incomes less than $65,000. The corporate tax rate in New Zealand is cut from 28 to 17.5 cents per dollar of profit, and the goods and services tax (GST) rate is increased from 15 percent to 17.5 percent.

In total, taxes are cut by $21.9 billion, or 9.1 percent of GDP (= $239.5bn). This reduction is made up of a $21 billion cut in personal taxes, a $4.1 billion cut in company taxes, and a $3.2 billion rise in GST.

Welfare Reform

At present, the New Zealand government funds welfare out of general taxation. In addition to health and risk cover (for unemployment, sickness, and disability) it also pays a pension. Under the new “savings not taxes” regime, the funds from the above tax cuts on income below $50,000 (or $65,000 for single-income families with children) go directly into the compulsory accounts. They are supplemented by an individual’s own contributions, and by the individual’s employer. Single taxpayers contribute 5 percent of earned income up to $50,000. Their employers pay another 12.5 percent of income up to $50,000. These add up to savings of $17,500 per year for each person earning $50,000 or more (and $22,750 for a single-income family with children on $65,000 or more).

The funds are used to help meet current health care and risk cover costs, as well as to build up savings for future payments in retirement. Smaller medical bills are paid directly whereas larger ones are funded by the purchase of catastrophic insurance plans. The government underwrites health and risk cover payments for those with insufficient savings (e.g., anyone who has been out of work for more than three years). Aggregate compulsory savings equal $28 billion.

Health Care

The share of public health care spending in New Zealand has remained relatively constant over the last decade at around 80 percent of total spending (well above the average of 72 percent in OECD nations). In the OECD’s upside “cost-pressure” scenario, public health and long-term care spending is forecast to increase to 15.3 percent of GDP by 2060.

Our new regime changes the health system’s source of funding and introduces transparent pricing of health care services. Each person builds up an HSA that receives 45 percent of the total compulsory savings or $7,875 (= 45% × $17,500).3 Most of one’s medical bills are paid out of this account. A prescribed level of savings is set for each person, and after it is reached the level of required savings is cut, increasing one’s disposable income. Total contributions to the health accounts are $12.6 billion (= 45% × $28bn) each year.

An annual catastrophic health insurance policy must also be taken out to cover medical events costing more than $20,000 in any one year (in 2015 dollars). This is paid for out of one’s savings account. Those earning more than $65,000 are expected to pay for part of their own health care, before drawing down their savings accounts. A 12.5 percent levy on the yearly health savings contributions of $1.6 billion (= 12.5% × $12.6bn) is made to help pay for the chronically ill, retired, and beneficiaries.

On the expenditure side, estimated drawdowns on the private HSAs in the first year of the reform equal $7.5 billion. The government funds a further $8.1 billion. As a result, the total amount spent on health remains the same at $15.6 billion. In other words, the drop in public spending is fully offset by more spending from the compulsory accounts.

One would expect significant gains in service provision for this same level of funding. Efficiency gains arise from more transparent pricing of health care services, the ending of third-party funding, and the encouragement of more personal responsibility. As people directly spend their own money to pay for smaller health care bills and purchase their own insurance plans rather than having others do it on their behalf, behavior should change.

Haseltine (2013) suggests that the size of the potential efficiency gains may be enormous. For example, total public and private sector health care spending in Singapore, which uses a similar system of health savings accounts to those proposed here, is nearly one-quarter of the level in the United States. Yet Singapore’s health outcomes are, if anything, better.

Retirement or Superannuation

At present, New Zealand pays a universal pension to people over 65 years of age who have completed modest residence requirements. It is flat rate (i.e., does not depend on previous income and is not means tested). The pension cost 5.1 percent of GDP in 2015 and is forecast to rise to 8.1 percent by 2050.4 The Labour government also introduced the Kiwi Saver scheme in 2007, which is a voluntary retirement savings scheme. Employees are automatically enrolled and contribute a percentage of their gross earnings, unless they choose to opt out. Employers and the government also make contributions.

Under the new regime, individuals build up their own Superannuation Fund account, which receives 35 percent of their total compulsory savings or $6,125 (= 35% × $17,500). For many people these contributions will replace their existing Kiwi Saver payments. Our new regime extends the retirement age from 65 to 70 years old over the next 20 years (i.e., by three months per year) and retains the government pension, although its source of funding changes. At the start of the reform, the pension continues to be funded out of general taxation, though it will be increasingly covered by the increase in retirement age and a 25 percent tax levied on the size of each individual’s Superannuation Fund on the date of retirement.

Total contributions to Superannuation Fund accounts are $9.8 billion (= 35% × $28bn) per year. Of this total, a pension levy of $2.5 billion (in 2015 values) is paid on retirement. The remaining $7.3 billion becomes savings that one is free to spend after retiring. In year one of the reform there are no withdrawals from accounts, whereas the government spends $10.6 billion on pensions. As the age of retirement rises, public spending on pensions falls under the new regime, compared to the present one.

Risk Cover: Unemployment, Sickness, Invalid, and Accident Coverage

Unemployment benefits in New Zealand are currently paid out of general taxation and are unlimited in duration. The government also provides support for people with a health condition, injury, or disability, and sponsors the Accident Compensation Corporation, which pays 80 percent of net wages to employed people who are unable to work due to accidents. These different schemes imply that the size of payments to an individual who is out of work depends on the cause of that unemployment. As a result there is an incentive to try to change category (e.g., from unemployed to sickness) in order to obtain a higher payment.

Under the new regime, individuals have a risk cover fund, which receives 20 percent of their total compulsory savings or $3,500 (= 20% × $17,500). A prescribed level of savings is set for the fund. Once reached, required contributions drop sharply. Should one become out of work, a drawdown occurs. If still out of work after 26 weeks, then a weekly payment is received from a catastrophic risk insurance policy (purchased with money in the fund). If one has insufficient funds in the savings account, or is jobless for more than 156 weeks, leaving one without insurance cover, then government assistance is given.

Total contributions to the risk accounts are $5.6 billion (= 20% × $28bn) per year. Estimated drawdowns in the first year of the reform equal $1.5 billion and the government funds a further $8.4 billion. Individuals have the choice to insure themselves at a higher level than the basic cover out of their own disposable income. Many higher-income earners would undoubtedly do so. Note that the payments that each out-of-work person receives no longer vary depending on the reason for absence from workforce.

Education

Primary and secondary schools in New Zealand are presently funded out of general taxation. Families may choose to pay for private education. The government also helps to fund early childhood education. There are no changes to the budget allocations for these programs under our proposed new regime, although an education tax credit would become available for any child whose family would like one.

University students, on the other hand, currently pay a subsidized fee for their degrees, and are also eligible for public grants. In 1992, the New Zealand government introduced a student loan scheme, which provides students with the opportunity to borrow for tuition fees, course costs, and living expenses. In 2006, student loans were made interest free.

Our reform retains the subsidized fee, but introduces a means test to restrict interest-free loans and grants to students from low-income, low-capital families. Note that university students may gain most from lower personal taxes under the new regime when they get older. The reduction in these grants equals $3.3 billion. As a consequence, education funding falls to $11.9 billion.

Other Welfare Expenses: Subsidies to Business, Kiwi Saver, and Working for Families

The government presently engages in a range of subsidies to business, which is sometimes called corporate welfare. It also subsidizes the Kiwi Saver scheme and funds the “Working for Families” (WFF) programme.

Corporate welfare includes a range of subsidies for broadband and fiber connections, movies that are “internationally focused and produced in NZ,” and support designed to maintain the strategic capabilities of industry. The total cost of these kinds of programs was $1.35 billion in 2015. In addition, a range of accelerated depreciation tax allowances are available to businesses in the forestry, farming, bloodstock, and research industries, as well as favorable treatment of rental housing. These subsidies and allowances are discontinued under our new regime.

The WFF program, meanwhile, consists largely of earned income tax credits. Since our new regime cuts taxes for lower-income earners and helps people to establish their own savings accounts, both WFF tax credits and Kiwi Saver subsidies are no longer necessary. Even so, the WFF budget is still largely retained, but is instead reoriented to guarantee that the disposable income of low- and middle-income working families with dependent children doesn’t fall while their accounts are set up.

Of these different types of spending, there is a $2.4 billion cut in subsidies to business and a drop in Kiwi Saver subsidies of $720 million under the new regime (i.e., $3.1 billion in total). As a result, “other” welfare spending falls to $19 billion.

Impact on the New Zealand Government’s 2015–16 Budget

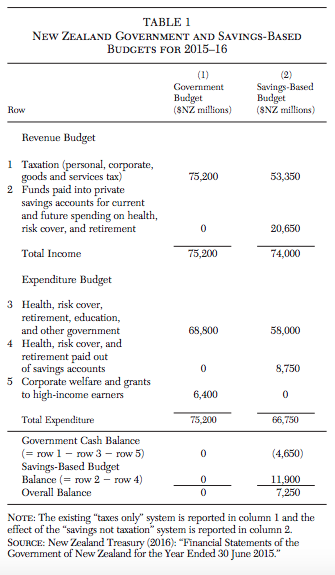

Under the present taxed-based system, revenues equal $75.2 billion. The government spent the same amount of cash, mainly on the welfare state, representing 31.4 percent of GDP. The first major impact of the new savings-based system is to cause tax revenues to fall to $53.4 billion. This comprises lower personal income and company taxes, as well as lower interest and dividend taxes. These reductions are partly offset by a rise in GST revenues. A total of $20.65 billion of the tax cuts is paid into the savings accounts for future welfare needs.

Consequently $74 billion of funds are available for spending by the government and by private individuals on their own welfare needs under the new regime. Funds not spent out of individual accounts in the current year become savings for future expenditures. The impact on the New Zealand budgetary accounts for 2015–16 are summarized in Table 1.

Note that our regime gives the government a somewhat larger role in terms of its being the “insurer of last resort” compared with the current system in Singapore. In other words, we allow the state to provide more assistance to those who cannot fully fund their own catastrophic health insurance, or make payments for smaller bills, or both.

The second major impact of the new regime is the funding of personal savings accounts. A total of $20.65 billion goes into these accounts to help contribute to each individual’s current and future personal health expenses and out-of-work income, and to pay for catastrophic health and risk cover insurance.

In the first year of the reform $58.0 billion of welfare and other spending is paid by government, comprising $8.1 billion on health, $10.6 billion on pensions, $8.4 billion on risk cover, $11.9 billion on education, and $19.0 billion on other expenses. By contrast, a total of $8.8 billion of spending is funded out of the accounts, comprising $7.5 billion on health and $1.3 billion on risk cover.

A total of $6.4 billion of subsidies to businesses and students from wealthy families are cut, which helps allow the tax cuts to be big enough to allow most people to establish significant savings balances. For a full set of current and forecast accounts, showing fiscal impacts, as well as details of the policy changes, see Douglas and MacCulloch (2016).

A Welfare “Savings Not Taxation” Reform for the United States

Although our focus has been on the New Zealand case study, the question arises as to whether this kind of reform would also be possible in the United States. Our answer is an emphatic “yes,” provided there is the political leadership and will to do it, and the required policies are packaged and presented in an appropriate way.

But why do we answer with a simple “yes”? Because the United States has so much room for reforming personal and business taxes. It would be relatively easy to lower tax rates dramatically, in return for the removal of various privileges. A reform of this nature would have many features that should appeal to both Republicans and Democrats. Since it replaces taxes and purchases of welfare services by third parties with mandatory savings that can be spent directly by individuals, the reform expands personal responsibility and freedom of choice. Furthermore, tax rate cuts are largest, percentage-wise, for low- and middle-income earners, and universal coverage is supported.

While we do not claim to be experts on the U.S. government’s revenue and expenditures, we are able to provide an outline of how the reform could be applied in this context.

Contributions to the personal savings accounts would be higher than in New Zealand, to cover higher health care costs. For an individual earning $US 60,000, there would be a total of around $US 21,000 in contributions each year. Of this total, the health care account would receive $US 11,375, the retirement account $US 6,125, and the risk account (for out-of-work coverage) $US 3,500. As in the New Zealand version of the reform, annual catastrophic health and risk insurance policies would be taken out by each individual, with smaller bills paid directly from one’s mandatory savings accounts.

So how would these savings, equal to 35 cents on the dollar for someone earning $US 60,000, be funded? It would look something like the following. Around $US 10,500 comes by way of personal income tax cuts, $US 3,000 from individual contributions, and $US 7,500 from employers (totaling $US 21,000). Although the government would lose $US 10,500 in tax revenues (for our base-case individual), this loss is offset, in the main, by a cut in current and future health, retirement, and out-of-work public expenditures.

The individual contributions of $US 3,000 would be paid in lieu of existing out-of-pocket health payments and retirement savings. As for the employer contributions of $US 7,500, these are largely offset by reductions in the health, retirement, and out-of-work payments that they presently make. The reform would also include significant tax cuts for employers (including corporations).

Government retains certain important roles, however, both as “insurer of last resort” in the health care and out-of-work areas, and as provider of vital information (e.g., prices for health services). As an example of how transparency can be promoted, the Singaporean Health Ministry publishes prices on its website for medical conditions, surgeries, procedures, ward classes, and more. The aim is to empower people with information for making the best decisions regarding high-quality, low-cost care, and to encourage competition between providers.

We believe the United States has the opportunity to cut taxes well beyond what is necessary to fund the savings accounts, as set out above. One way to achieve this goal, while reducing the fiscal deficit, would be to cut government spending on huge privileges for special interest groups. These include grants to individuals—such as tax deductions on mortgage interest, low-income housing, business use of cars, and interest on student loans—as well as corporate welfare (i.e., subsidies to small businesses, large corporations, and industry organizations). Corporate welfare forms part of the programs of the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Energy, and Housing and Urban Development (De Haven 2012). Hundreds of billions of dollars could suddenly become available for personal and business tax cuts.

As noted earlier, the size of the potential efficiency gains from these changes is likely to be enormous. In health care alone, where the annual tax subsidy to employer-provided insurance has fueled the purchase of first dollar insurance plans, total public and private spending is presently 17.2 percent of GDP. However, Singapore’s experience suggests that, when individuals pay directly for smaller bills and buy catastrophic insurance cover out of their own savings accounts, health care spending can be reduced while outcomes improve. The welfare “savings not taxation” reform is designed to ensure that everyone has the funds to make these payments. It seeks to remove third-party payers, whether they are the government or employers.

In other words, the United States has a choice. It can maintain its complex tax code with all sorts of exemptions or, for example, have a tax system along the following lines: zero taxes on incomes from $0 to $US 60,000, a 20 percent rate from $US 60,000 to $US 120,000, and a 25 percent rate on incomes greater than $US 120,000. People would, in these circumstances, become responsible for any additional health care, retirement, or risk cover they wished to take out beyond what they received from their savings accounts.

In New Zealand, most corporate welfare was abolished in the 1980s and 1990s, based partly on a view that individuals are better investment managers than the state. Those changes also helped balance the government budget. For example, business concessions such as export incentives, accelerated depreciation allowances, and subsidies to agriculture were ended. Many individual concessions were also stopped, such as life insurance tax exemptions and rebates on interest payments for first home mortgages (Walker 1989).

The savings (and corresponding extra government income) that followed these changes allowed a key political strategy to be implemented in the form of large cuts in tax rates (e.g., the top personal income tax rate was halved from 66 percent to 33 percent). While corporate rates were also cut dramatically, the overall package proved to be politically popular, with the government of the day increasing the number of seats it held at the next election.

A similar package to the one outlined above, except this time for the United States, would prove to be equally popular, in our opinion. Significant efficiency gains are likely to arise from the changes to health care and risk cover, the removal of corporate welfare and other forms of privilege, and the tax cuts. Those changes would also allow individuals to accumulate large balances in their savings accounts to meet future health care and other needs in retirement. The fiscal gap of the U.S. government can be closed, and the system as a whole can become fully funded.

Conclusion

What kinds of outcomes can we expect from the new “savings not taxation” regime? First, consumers would now spend their own money (for health and risk cover) and save for their retirement. A culture of greater personal responsibility should develop, helping to control costs and increase quality. Consumers would become the principal buyers of welfare services, as they are for other goods and services, instead of third parties. Choice would become available for most people, not just the rich, creating a sense of empowerment.

Second, transparent price comparisons would become possible, particularly in the health services area, which should improve efficiency. Third, the primary role of government changes from funder and provider to regulator, information provider, and insurer of last resort. Fourth, the personal goals of disadvantaged people would be recognized.

In summary, a reform of this type has the potential to lead to significant efficiency gains. It should also help secure the future of the welfare state, while at the same time retaining the necessary tax revenues to ensure universal coverage and equitable outcomes.

References

Cannon, M. (2006) “Health Savings Accounts: Do the Critics have a Point?” Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 569.

De Haven, T. (2012) “Corporate Welfare in the Federal Budget.” Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 703.

Douglas, R. (1989) “The Politics of Successful Structural Reform.” Paper presented at the Mont Pelerin Society, Christchurch, New Zealand (November 28).

Douglas, R., and MacCulloch, R. (2016) “Welfare: Savings Not Taxation.” Working Paper No. 31890, University of Auckland Economics Department.

Evans, L.; Grimes, A.; Wilkinson, B.; and Teece, D. (1996) “Economic Reform in New Zealand 1984–95: The Pursuit of Efficiency.” Journal of Economic Literature 34 (4): 1856–1902.

Haseltine, W. (2013) Affordable Excellence: The Singapore Healthcare Story. Washington: Brookings Institution.

Kotlikoff, L. (2013) “Assessing Fiscal Sustainability.” Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

New Zealand Treasury (2016) “New Zealand: Economic and Financial Overview 2016.”

OECD (2013) “What Future for Health Spending?” OECD Economics Department Policy Notes No. 19 (June).

Shiller, R. (2004) “Saving a World that Doesn’t Save.” Project Syndicate (February 6).

Walker, S. (1989) Rogernomics: Reshaping New Zealand’s Economy. Auckland: New Zealand Centre for Independent Studies and GP Books.

1All currency amounts in this article are in New Zealand dollars, unless otherwise stated (e.g., $US).

2The Public Finance Act 1989 in New Zealand promoted a move in this direction.

3Cato Institute scholars first proposed (voluntary tax-incentivized) HSAs in the 1980s and were leaders in popularizing them among the public and policymakers. See, for example, Cannon (2006).

4Although the pension is paid out of general taxation, the Labour government established a Superannuation Fund in 2001 to help partially prefund future payments. Contributions are financed out of taxes but were suspended in 2009. Latest estimates suggest that about 8 percent of the expected cost of the pension in 2050 will come from the Superannuation Fund.