Monetary instability poses a threat to free societies. Indeed, currency instability, banking crises, soaring inflation, sovereign debt defaults, and economic booms and busts all have a common source: monetary instability. Furthermore, all these ills induced by monetary instability bring with them calls for policy changes, many of which threaten free societies. One who understood this simple fact was Karl Schiller, who was the German Finance Minister from 1966 until 1972. Schiller’s mantra was clear and uncompromising: “Stability is not everything, but without stability, everything is nothing” (Marsh 1992: 30). Well, Schiller’s mantra is my mantra.

I offer three regime changes that would enhance the stability in what Jacques de Larosière (2014) has asserted is an international monetary “anti-system.” First, the U.S. dollar and the euro should be formally, loosely linked together. Second, most central banks in developing countries should be mothballed and replaced by currency boards. Third, private currency boards should be permitted to enter the international monetary sphere.

On the Dollar-Euro Linkage

In 1944, the Bretton Woods agreement established a new global monetary system. Its hallmark was exchange rate stability. That stability was accompanied by a general acceleration of growth in the postwar golden age. By 1973, the system had been swept into the dustbin by the broom of President Richard Nixon. With that, the world entered an era of flexible, unstable exchange rates, de Larosière’s anti-system.

This exchange rate instability creates problems—big problems. Just look back to the onset of the Great Recession in 2008. As it turns out, one of the few who had a laser focus on what he deems the most important price in the world, the dollar-euro exchange rate, was Robert Mundell. A founding father of supply-side economics, Mundell is always focused on prices. That certainly separates Mundell from Ben Bernanke, who was chairman of the Federal Reserve back in September 2008. Bernanke saw fit to ignore fluctuations in the value of the dollar. Indeed, changes in the dollar’s exchange-rate value did not appear as one of the six metrics on “Bernanke’s Dashboard”—the one the chairman used to gauge the appropriateness of monetary policy (Wessel 2009).

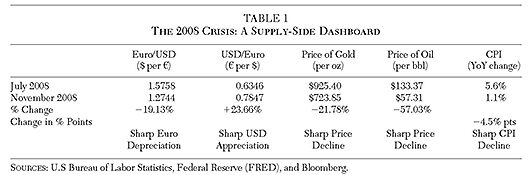

Just what did Mundell take stock of in the months surrounding the collapse of Lehman Brothers, Inc. (Mundell 2009)? He observed a wild swing in the dollar-euro exchange rate (see Table 1). In the July–November 2008 period, the greenback appreciated almost 24 percent against the euro. Accompanying that swing was an even sharper one in the price of oil. It plunged by 57 percent. Gold, too, had a sharp fall of almost 22 percent. And, consistent with Mundell’s supply-side theories, changes in exchange rates transmit inflation (or deflation) into economies, and they can do so rapidly. Not surprisingly, then, the annual rate of inflation in the United States moved from an alarming rate of 5.6 percent in July 2008 to an outright deflation of 2.1 percent a year later. This 7.7 percentage-point swing is truly stunning.

So, in terms of monetary policy, Mundell saw the obvious: the Fed was too tight—massively too tight. The dollar was soaring and commodity prices were collapsing. Fed Chairman Bernanke saw none of this because exchange rates weren’t even on his dashboard. Alas, the Fed’s massive monetary squeeze and resulting unstable dollar plunged the United States into what would become known as the Great Recession. The instability also generated an avalanche of legal and regulatory changes, such as the Dodd-Frank legislation. These changes restricted economic freedom.

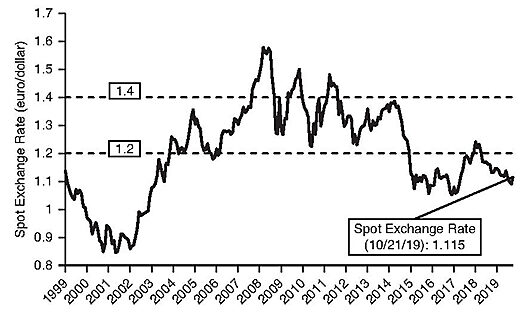

So, in the interest of stability and economic freedom, it is time to jettison the international monetary anti-system. Just what has to be stabilized? The world’s two most important currencies—the dollar and the euro—should, via formal agreement, trade in a zone of stability ($1.20–$1.40 per euro, for example). Under such an agreement, the European Central Bank (ECB) would be obliged to maintain this zone of stability by defending a weak dollar via dollar purchases. Likewise, the U.S. Treasury (UST) would be obliged to defend a weak euro by purchasing euros. Just what would have happened under such a system (counterfactually) since the introduction of the euro in 1999 is depicted in Figure 1. When the euro-dollar exchange rate was less than $1.20 per euro and the euro was weak, the UST would have been purchasing euros (in the 1999–2003 and the 2014–2019 periods). When the euro-dollar exchange rate was above $1.40 per euro and the dollar was weak, the ECB would have been purchasing dollars (in some of the 2007–2011 period).

FIGURE 1: EURO/DOLLAR EXCHANGE RATE ($ per €)

SOURCE: Bloomberg.

On Currency Boards for Developing Countries

On Private Currency Boards

For many years, my long-time currency board collaborator Kurt Schuler and I have advocated on behalf of private currency boards (Hanke and Schuler 1994). In our draft law for such a currency board, we proposed that its home offices and reserves be located in Switzerland and that it be governed under Swiss law.

With the advent of cryptocurrencies, the prospect of our idea, or something close to it, is close to becoming a reality. Indeed, the white paper issued by the Libra Association (2019) explicitly states that the Libra cryptocurrency would be similar to a currency board. In broad terms, that is correct. However, Libra is not yet a reality and, as Steve Forbes (2019: 15) recently pointed out:

Nonetheless, regulatory pressures have forced a number of companies that were partnering with Facebook on this project to drop out. And this gets to the real reason the idea of Libra is so troubling to so many politicians, government bureaucrats, banks and economists the world over: Libra could do to central banks what Uber and Lyft did to the taxi cartels—bust up their monopolies, or, to coin a phrase, give them a run for their money.

Central banks are clearly feeling the competitive threat posed by the prospect of private currency boards (like Libra). Indeed, a recent report on digital currencies by the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum in London and IBM presents results from a survey of 23 central banks (OMFIF and IBM 2019). Half of the respondents indicated that they perceived the widespread use of decentralized, private digital currencies as a real threat. As the central bankers put it, private currencies would potentially “disturb the global financial system and undermine the sovereignty of monetary authorities” (OMFIF and IBM 2019: 19).

Not surprisingly, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has recently changed its position toward digital currencies. The BIS had been opposed to the introduction of such currencies, whether they be private or public. Now, the BIS has tasked Benoît Coeuré, who sits on the BIS Executive Board, with the development of central bank digital currencies to combat private challengers. As Financial Times reportage recently recounted: “BIS officials believe central banks should pool their resources to fend off potentially disruptive competition from better funded private sector rivals” (Kaminska 2019: 4).

Conclusion

To thrive, free societies must experience stable money. With the advent of central banking, particularly in developing countries, a great deal of instability ensued. And with instability, laws and regulations have been introduced that have restricted individuals’ economic freedom.

Stability in the monetary realm would be promoted if the center was made stable by linking the U.S. dollar and euro exchange rates. The periphery would be made stable by mothballing central banks and replacing them with currency boards that issue currencies that are clones of the currencies issued at the center—the U.S. dollar or euro. The prospect of private currency boards—which are backed by fiat currencies, baskets of currencies (like SDRs) or gold—appear to be a promising reality. The competitive forces that will be unleashed by the private alternatives would be a great stabilizer and enhance economic freedom and free societies.

References

Agence France-Presse (1998) “US Should Be More Tolerant Toward Indonesia: Japanese Economist.” Agence France-Presse (June 20).

__________ (1999) “Former Aussie PM says US Used Asia Crisis to Oust Suharto.” Agence France-Presse (November 11).

Coats, W. (2007) One Currency for Bosnia: Creating the Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Ottawa, Ill.: Jameson Books.

de Larosière, J. (2014) “Bretton Woods and the IMS in a Multipolar World?” Keynote Speech at Conference on “Bretton Woods at 70: Regaining Control of the International Monetary System,” Workshop No. 18 (February 28). In Workshops: Proceedings of OeNB Workshops, 180–85. Vienna: Oesterreichische Nationalbank.

Forbes, S. (2019) “With Libra, Zuck Is a Hero.” Forbes Magazine (November 30): 15.

Greenwood, J. (2008) Hong Kong’s Link to the U.S. Dollar: Origins and Evolution. Aberdeen, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Hanke, S. H. (1996/1997) “A Field Report from Sarajevo and Pale.” Central Banking 7 (3).

__________ (2000) “The Disregard for Currency Board Realities” Cato Journal 20 (1): 49–58.

__________ (2002a) “Currency Boards.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 579: 87–105.

__________ (2002b) “On Dollarization and Currency Boards: Error and Deception.” Journal of Policy Reform 5 (4): 203–22.

__________ (2008) “Why Argentina Did Not Have a Currency Board.” Central Banking 18 (3): 56–58.

__________ (2016) “Remembrances of a Currency Reformer: Some Notes and Sketches from the Field.” Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise Studies in Applied Economics Series (55).

Hanke, S. H., and Boger, T. (2018) Inflation by the Decades. Washington: Cato Institute.

Hanke, S. H.; Jonung, L.; and Schuler, K. (1993) Russian Currency and Finance: A Currency Board Approach to Reform. New York: Routledge.

Hanke, S. H., and Krus, N. (2013) “World Hyperinflations.” In R. E. Parker and R. Whaples (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Major Events in Economic History, 367–77. New York: Routledge.

Hanke, S.H., and Li, E. (2019) “The Cayman Currency Board: An Island of Stability.” Cayman Financial Review 54: 26–27.

Hanke, S. H., and Schuler, K. (1991) “Keynes’s Russian Currency Board.” In S. H. Hanke and A. A. Walters (eds.), Capital Markets and Development, 43–58. San Francisco: ICS Press (Institute for Contemporary Studies).

__________ (1994) Currency Boards for Developing Countries: A Handbook. San Francisco: ICS Press (Institute for Contemporary Studies).

Hanke, S. H., and Sekerke, M. (2003) “St. Helena’s Forgotten Currency Board.” Central Banking 13 (3).

Hanke, S. H., and Tanev, T. (2020) “Bulgaria: Long Live the Currency Board.” Central Banking 30 (3): 140–45.

Hicks, J. (1967) Critical Essays in Monetary Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

__________ (1989) A Market Theory of Money. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Kaminska, I. (2019) “BIS Turns to Cœuré in Push Towards Digital Currency.” Financial Times (November 12).

Libra Association (2019) “An Introduction to Libra.” Available at https://libra.org/en-US/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2019/06/LibraWhitePaper_en_US.pdf (June 23).

Marsh, D. (1992) The Bundesbank: The Bank that Rules Europe. London: Mandarin Paperbacks.

Mundell, R. (2009) “Financial Crises and the International Monetary System.” Columbia University, New York (March 3). Available at: www.slideshare.net/bartonp/mundell-financial-crises-and-the-intl-monetary-system.

Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum (OMFIF) and International Business Machines (IBM) Corporation (2019) “Retail CBDCs: The Next Payments Frontier.” Available at: www.omfif.org/ibm19/ (October 29).

Sanger, D. E. (1999) “Longtime I.M.F. Director Resigns in Midterm.” New York Times (November 9): C1–C3.

Schuler, K. (1996) Should Developing Countries Have Central Banks? Currency Quality and Monetary Systems in 155 Countries. London: Institute of Economic Affairs.

__________ (2005) “Ignorance and Influence: U.S. Economists on Argentina’s Depression of 1998–2002.” Econ Journal Watch 2 (2): 234–78.

Tyson, J. L. (1999) “‘Dollar Diplomacy’ Rises Again as Foreign-Policy Tool.” Christian Science Monitor (February 10): 2.

Wessel, D. (2009) In Fed We Trust: Ben Bernanke’s War on the Great Panic. New York: Crown Business.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.