Our work on “reverse” monetary policy transmission is the first analytic work on how transmission takes place from collateral in the market to short-term market rates (Singh and Goel 2019). The use of long-dated securities as collateral for short tenors—for example, in securities lending, derivatives, repo markets, and prime brokerage funding—also impacts the risk premia (or moneyness) along the yield curve. In this article, we show that transactions using long-dated collateral, post-Lehman (i.e., following the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008), are fewer, and have adversely impacted the transmission to short-term market rates. Our results suggest that the unwind of central bank balance sheets will likely strengthen the monetary policy transmission.

Some Background

Historically, most monetary policy research tries to explain the term “premia” using the expected path of future short-term rates. This approach is in line with the standard monetary policy transmission mechanism whereby central banks generally target a short-term rate. These short-term rates, combined with investors’ preferences at different maturities of the yield curve (also called the “preferred habitat hypothesis”) and fundamental economic factors, pass through to the long-term rates. This transmission channel has been researched extensively in the literature (e.g., Del Negro et al. 2017). We all have been taught that short-term policy rates drive the whole yield curve—specifically, that market expectations about the future path of the overnight federal funds rate are reflected in 10-year yields and beyond.

In recent years, that transmission mechanism has broken down, with policy rate hikes not percolating to the long end of the yield curve. Since the Fed’s lift-off in December 2015, from zero to 2.5 percent, the 10-year Treasury yield actually declined from 2.30 percent to around 2.0 percent (before the most recent rate cut(s) starting in July 2019, and now to zero on the back of Covid-19).

Less well understood is the reverse transmission mechanism, from long-term bonds to short-end rates. This happens as a result of the reuse of long-tenor bonds as collateral in repo, prime brokerage, derivatives, and securities lending markets. The use of longer-term bonds as collateral in money markets can change the effective supply and demand dynamics at the long end, which then feeds back into short-term rates. For instance, if there is a greater supply of long-term collateral available to pledge in the repo markets, money market funds will increase overnight lending and purchase fewer T‑bills, causing short-term rates to rise. This is even more relevant in the postglobal financial crisis era, when the collateral market has declined sharply and the expected short-term rates were bolted near zero by quantitative easing (QE). As background, in the aftermath of QE or a variant thereof, expanded central bank balance sheets that silo sizable holdings of U.S. Treasuries, U.K. gilts, Japanese government bonds, German bunds, and other AAA (or somewhat lower) eurozone collateral have placed central bankers in the midst of market plumbing that determines the short-term rates. Given their sizable footprint in the market for such collateral, it will be very difficult for them to walk away from that role. Thus, this channel and the potential implications for the monetary policy transmission are critical to examine.

Our research shows that a $1 trillion change in pledged collateral can move short-term rates by as much as 20 basis points (bp). However, this reverse transmission mechanism has also broken down of late. The 2008 financial crisis led to a structural change in the collateral markets. The longer-term pledged collateral market grew to about $10 trillion pre-Lehman. Immediately after Lehman’s bankruptcy, this market collapsed to about half its peak and remained unchanged until 2016. This decline was initially due to crisis-related haircuts and counterparty risk in dealers and was cemented by QE and regulatory changes.

Initially, QE lowered long-tenor spreads as central banks took duration risk out of the market. This also meant there were fewer long-tenor bonds to pledge in the collateral markets, which compressed short-term rates. Then, regulatory changes—such as the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR), which requires banks to maintain sufficient holdings of high-quality liquid assets (HQLAs) to cover stressed outflows—had a similar effect.

Research Intuition

In general, high quality bonds, when pledged with title transfer, are constantly reused in a process that is akin to the money creation that takes place when banks take deposits and make loans. For global banks that are active in the pledged collateral market, there are two primary sources that pledge collateral to the banking system: hedge funds and other financial intermediaries. In 2007, the collateral velocity (or reuse rate) was $10 trillion/$3.3 trillion, or about 3.0.1 Collateral velocity has been lower in recent years, initially due to the Lehman crisis and elevated counterparty risk in global systematically important banks (GSIBs). In subsequent years, the reuse of collateral was constrained due to regulations that restrict dealer banks’ balance sheet space (e.g., via the leverage ratio), and due to central banks’ purchases of good collateral (under various QE programs). However, as of year-end 2018, the pledged collateral received by the major banks that could be repledged in their own name was around $8.1 trillion, an increase of 33 percent relative to year-end 2016, with almost all GSIBs active in peddling pledged collateral globally.

Excess reserves held at central banks and collateral available to pledge have very different implications for market functioning. Collateral in the market, with reuse, is likely to lubricate markets, while excess reserves have remained idle in recent years. Movements in short-term rates will be more elastic (and higher) if collateral reuse and/or supply of collateral increases. With a large U.S. Treasury pipeline for the issuance of short-tenor bills, the supply of collateral is likely to increase relative to cash (and recent market rates show this trend).2 For example, overnight rates in the eurozone would probably be much more negative if not for securities lending activity by national central banks. This has helped contain negative yields by effectively replacing longer-term bonds bought via QE with similar collateral and “moneyness” services to the market (see Appendix).

Analytics and Results

For almost a decade after the Lehman crisis, there was a continuous decline in collateral reuse due to a combination of QE, regulatory changes, and balance sheet constraints at large dealer banks. During this period, transmission to short-end rates remained muted. The effect has been most noticeable in the 6- to 12-month part of the curve, where the utility of collateral peaks, with enough tenor for reuse and limited duration risks. In our recent research paper (Singh and Goel 2019), we document the impact of collateral demand on the yield-curve risk premia.3 We regress the risk premia variable—the actual yield minus overnight index swap (OIS) forwards—at the 3‑, 6‑, 12‑, and 24-month points against our measure of global collateral and a proxy:

Risk Premia = α + β * Global Colleteral + ∑γ * Proxy.

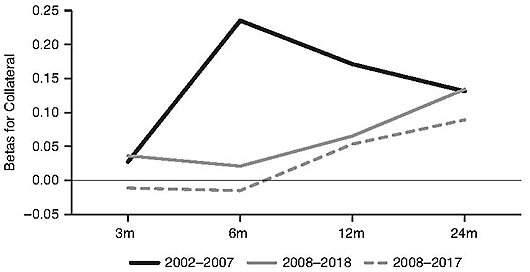

Figure 1 shows the change in risk premia associated with a $1 trillion change in the supply of collateral over a 3- to 24-month horizon. The kink in the 6- to 12-month points confirms the “moneyness” concept in the pledged collateral market (Jiang, Krishnamurthy, and Lustig 2019; also Appendix). The price volatility of longer-term bonds diminishes their value as collateral, while very short-term securities must be replaced frequently, at a cost. Thus, securities with six months to two years to maturity occupy a “sweet spot,” which is reflected in risk premia.

FIGURE 1: REVERSE TRANSMISSION IS WEAKER NOW: BETA COEFFICIENTS ACROSS DIFFERENT TENORS

Prior to the collapse of Lehman, a $1 trillion change in pledged collateral (the black line in Figure 1) resulted in an approximately 20bp change in this sweet spot. Post-Lehman, that relationship largely vanished and became statistically insignificant (the gray lines in Figure 1). In other words, monetary transmission from the long-tenor collateral market is weaker and near absent relative to pre-Lehman days.

Since 2017, the role of pledged collateral markets has started to improve. Large banks that are active in peddling collateral globally are optimizing their businesses to accommodate new regulations that constrain balance sheet space. The unwind of QE (until July 2019) has also contributed to the recovery of collateral markets, as excess reserves are drained, and securities are released. This should be good news for markets—and would increase short-term rates in the 6- to 24-months parts of the curve. However, dealer balance sheet space remains constrained. This was evident from the Fed stepping in initially to intermediate and “complete” markets that large dealer banks should have done (e.g., swap off-the-runs Treasuries to on-the-run Treasuries for their clients and their own books). Subsequently, Covid-19 related issues forced the Fed (with U.S. Treasury and Congress’s approval under the Dodd-Frank Act) to use “unusual and exigent” circumstances, in March 2020, and provide funding to the nonbank sectors.

Policy Considerations

The reemergence of an active collateral market also raises new questions about the continuing need for large central bank balance sheets. As a result, the dealer banks that connect the money pools and collateral pools will unwind such connections. Without money, the dealer banks will return the U.S. Treasury and agency MBS back to the securities-lenders in exchange for corporates/equities. The dealer banks will also give back securities to the hedge funds, as banks will not have funds from money market and other sources. So, the cost of funding long positions for nondealers, like hedge funds in the bilateral collateral market, will go up and demand for (and price of) securities will go down. Thus, the value of the pledged collateral (such as U.S. Treasuries) falls—whether the Fed sells them from their balance sheet or does reverse repos directly with nonbanks. Going forward, the role of central banks in market plumbing, due to large balance sheets that have kept collateral velocity muted, will impact their monetary policy.

If central banks remain part of the plumbing and take money directly from nonbanks, the financial plumbing that relies on such money gets rusted—this was the crux of the recent mid-September 2019 crisis when the money/collateral ratio decreased (causing a spike in market rates such as repo). Such “direct pipes,” which take money straight to the Fed, skirt the market plumbing and disconnect the dealer banks from the money pools and collateral pools—an important nexus that determines market rates.

In many respects, collateral availability and ample excess reserves both contribute to well-functioning money markets. Traditionally, the former market-oriented approach played a more prominent role. It is not immediately clear why reserves are now preferred to money-like U.S. Treasuries or bunds. New liquidity regulations (e.g., resolution liquidity funding needs, and/or intraday stress testing) suggest a bias toward reserves over U.S. Treasuries.

The holdings of HQLA across global banks do vary, with some banks holding more collateral and others biased toward reserves. There are several reasons for this, including the fact that some banks make a market in reserves (Kaminska 2019), while others prefer collateral and its reuse potential to reserves. As an analogy, oil is only needed for lubricating a car’s engine; similarly, excess reserves are needed only to smooth out the intraday need for reserves in the financial system. They were close to zero before the Lehman crisis. Now instead of an “oil change” we are carrying the oil in the car trunk, in our homes, everywhere.

Federal Reserve research suggests that removing the asymmetry of reserves holdings will reduce the overall need for reserves in the financial system (Afonso, Armenter, and Lester 2018). Creating a Fed standing repo facility (SRF), which could be used during a crisis to provide credit at a slightly punitive rate to market rates, if designed well, could make systemic intraday payment overdrafts less risky—and remove the bias of cash over Treasuries (Andolfatto and Ihrig 2019; Ihrig et al. 2019). However, with dealer balance sheets now relatively more elastic than at any point since the financial crisis, a smaller footprint of central banks will likely improve the financial system’s plumbing and monetary policy transmission.

European Central Bank economist Ulrich Bindseil, in his Jackson Hole speech (Bindseil 2016), suggested that lean balance sheets would reflect a healthy focus of central banks on their core mandate (long-run price stability) and that large balance sheets should therefore be linked to exceptional periods in which the effective lower bound to short-term interest rates is binding (although postcrises balance sheet normalization takes time). In his words:

[An] outstandingly lean central bank balance sheet was the one of the Fed precrisis, where the total balance sheet length was only around 1.1 times the total amount of bank notes in circulation. In general, the objective of a lean balance sheet should remain valid in the future long-term Operating Framework, even if monetary and FX policies, or in some cases auxiliary central bank tasks, can justify some lengthening.… [T]he idea that the central bank permanently injects monetary accommodation through a longer balance sheet with substantial holdings of a portfolio of less liquid assets with long maturity and possibly some credit riskiness does not appear sufficiently convincing.

Conclusion

Looking forward, what does the central banks’ balance sheet unwind and forthcoming regulatory tweaks entail for money market rates? First, excess reserves are not the only way to satisfy HQLA need; good collateral like U.S. Treasuries or German bunds also substitute as HQLA. Second, the unwind of good collateral like U.S. Treasuries or bunds from central bank balance sheets to the market is likely to improve transmission to the short-end money market rates. Deposits with the banks doubled after the demise of Lehman. That is a huge change for the banking system to absorb in a span of three to five years. The banks’ asset side also has to grow in line with deposit growth, but the new regulatory rules (e.g., the leverage ratio) leave “little space” and thus constrain nondeposit activity such as repo transactions.

The dealer balance sheets are still constrained. Q4, 2019, trends in triparty repos suggest that dealer balance sheets are constrained for all collateral flows; hence triparty repos pick up the slack and are now inching higher (Gabor 2019).

However, they have been adjusted to the new regulations for transactions that are profitable per unit of balance sheet space. In the new regulatory era, there is a bias toward collateral transactions that straddle securities lending, prime brokerage, and derivatives since they are more attractive relative to repos involving a U.S. Treasury (a low margin and thus unattractive transaction from a bank’s profit-and-loss angle). Since dealer balance sheet space is the only alternative to a central bank balance sheet supporting the repo market, regulations should be tweaked so that cash (i.e., central bank reserves) and U.S. Treasuries are as equal as possible (Quarles 2020). On this front, suggestions include that resolution liquidity tests assume a “maximum” haircut on U.S. Treasuries that will be no larger than the discount window (i.e., the banks’ models will recalibrate the worst-case scenario and thus reduce the need for holding reserves, freeing up their balance sheets for making a market in U.S. Treasuries). However, Covid-19–related bailouts will keep central banks’ footprint for even longer, unless regulations are softened to allow dealer banks more balance sheet capacity. (We are happy to see regulations are now softened to allow dealer banks more balance sheet capacity—for example, exempting U.S. Treasuries and reserves from the leverage ratio.)

Central bank arguments for large balance sheets in normal times warrant further research. For example, there need to be underlying economic arguments about why reserves should be preferred over money-like U.S. Treasuries. Also, the need for large excess reserves for a cyber-attack event are not obvious when liquidity coverage and related regulations for a wholesale deposit “run” are more apt. Some recent attempts to show the impact of QE on limiting collateral reuse from long-tenor bonds (Jank and Moench 2020) are in the right direction, but data are limited to the eurozone and the German bunds, whereas the pledged collateral market is global.

More frequent data reporting on all collateral flows by global banks that are active in this market will be a welcome move to enhance our understanding of the transmission from long-term bonds to short-end market rates. For example, FR2004 (a Federal Reserve form used to collect information on market activity from primary dealers in U.S. government securities) has a weekly frequency, but it does not provide details of all collateral flows (e.g., prime brokerage or derivative margins). Bilateral collateral transactions straddle not only repo and securities lending, but also a sizable pool is from prime brokerage and increasing derivative margins as central clearing counterparty (CCP) regulations are implemented in 2020.

It would also be useful to discern to what extent the regulatory need for collateral has adversely impacted the pledged collateral market. The market plumbing in the aftermath of new regulations and QE has changed. This makes pinning down the collateral velocity metric difficult because collateral flows have taken new directions—for example, the growth in ETFs since equity markets buoyed at the expense of fixed income, and securities lending programs by national banks.

Finally, none of the commonly used financial conditions indices (FCIs) adjusts for dealer balance sheet space. Given the increasingly important role these FCIs play in policy objectives, it is important to understand empirically the role played by the pledged collateral market.

Appendix: Moneyness

As discussed earlier, regression models used in the literature are asymmetric because they ignore the possibility that changes in supply and demand for long bonds could also affect the short-term market rates, and in turn, the management of the policy rate. There are premia for holding tenor that reflects the services—collateral, alternatives to deposits, regulatory need for HQLA, duration, and so on—that long-term bonds provide to pension, insurers, sovereign wealth funds, hedge funds, and the banking system, in addition to any required compensation for uncertainty about the future level of short rates.

The utility value of securities as collateral—the ease with which this instrument can be used to provide credit support for some (continuing) exposure—itself has several features. These include: (1) acceptability to counterparties worldwide; (2) ease of use—how likely it is to suddenly become special, how stable supply is; and (3) stability of price (i.e., expected frequency of posting and recalling margin).

Everyone will accept short-term Treasury bills (T‑bills) for everything, but not everyone will accept long bonds—so T‑bills will be preferred to bonds on the basis (metric 1). A collateral possessor will have to replace a one-week T‑bill every week, and replacing a maturing security entails a larger and more costly operation than holding a non-maturing security—so somewhat longer-term securities possess more collateral value (metric 2). Long bonds have a much higher price volatility, so their value as collateral is diminished (metric 3). Thus, a bill or short coupon with six months to two years to maturity occupies a “sweet” spot, where collateral is easily traded; it provides the highest collateral utility value—intuitively there is a “kink” at the sweet spot.

At the long end, where collateral utility value is eroded by price volatility, the value of duration-matching services for pension and life insurance investors tends to overwhelm the value of collateral services in setting term premia. For instance, the demand for long principal strips with a 3 percent yield seems to be a cap on long U.S. Treasury rates, as demonstrated by the recent tussle at the 3 percent rate for the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond. In the eurozone, the general collateral overnight rate for the German bund is about negative 50 bps.4 These rates would probably be much more negative if not for recent securities lending activity by the European Central Bank. This has helped contain negative yields by effectively replacing longer-term bonds bought via QE, with similar collateral and moneyness services to the market. At the very shortest end (e.g., three months), the value of the securities to nonbank institutions as a direct alternative to holding bank deposits (i.e., the moneyness) generally overwhelms the reuse value of collateral.

So, short-intermediate collateral, generally speaking, contributes most to collateral reuse and the overall liquidity of the financial system. We mention moneyness in relation to short securities, but it is important to note that this characteristic exists on a spectrum. It is not binary.

References

Afonso, G.; Armenter, R.; and Lester, B. (2018) “A Model of the Federal Funds Market: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Staff Report No. 840.

Andolfatto, D., and Ihrig, J. (2019) “Why the Fed Should Create a Standing Repo Facility.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, On the Economy Blog (March 6).

Bindseil, U. (2016) “Evaluating Monetary Policy Operational Frameworks.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole Symposium on “Designing Resilient Monetary Policy Frameworks for the Future.”

Del Negro, M.; Giannone, D.; Giannoni, M. P.; and Tambalotti, A. (2017) “Safety, Liquidity and the Natural Rate of Interest.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Spring): 235–316.

Gabor, D. (2019) “How RTGS Killed Liquidity: U.S. Triparty Repo Edition.” Financial Times Alphaville (October 11).

Ihrig, J.; Kim, E.; Kumbhat, A.; Vojtech, C. M.; and Weinbach, G. C. (2019) “How Have Banks Been Managing the Composition of High-Quality Liquid Assets?” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 101 (3): 177–201.

IMF (2018) Global Financial Stability Report April 2018: A Bumpy Road Ahead. Washington: International Monetary Fund.

Jank, S., and Moench, E. (2020) “Safe Asset Shortage and Collateral Reuse.” (Forthcoming).

Jiang, Z. Y.; Krishnamurthy, A.; and Lustig, H. (2019) “Foreign Safe Asset Demand and the Dollar Exchange Rate.” NBER Working Paper No. 24439.

Kaminska, I. (2019) “Don’t Fear the Year-End Funding Squeeze.” Financial Times Alphaville (January 29).

Quarles, R. K. (2018) “Liquidity Regulation and the Size of the Fed’s Balance Sheet.” Remarks at the Hoover Institution Monetary Policy Conference, Stanford University (May 4).

___________ (2020) “The Economic Outlook, Monetary Policy, and the Demand for Reserves.” Remarks at New York University (February 6).

Singh, M. (2019) “Collateral Velocity Is Rebounding.” Financial Times Alphaville (May 22).

___________ (2020) Collateral and Financial Plumbing. 3rd ed. London: Risk Books.

Singh, M., and Goel, R. (2019) “Pledged Collateral Market’s Role in Transmission to Short-Term Market Rates.” IMF Working Paper No. 19/106 (May).

About the Authors

Manmohan Singh and Rohit Goel both work for the IMF’s Monetary and Capital Markets Department. Singh is the author of Collateral and Financial Plumbing (2020). All views expressed are of the authors only, and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its executive board, or its management.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.