When I was at the Federal Reserve, I occasionally observed that monetary policy is 98 percent talk and only two percent action. The ability to shape market expectations of future policy through public statements is one of the most powerful tools the Fed has. The downside for policymakers, of course, is that the cost of sending the wrong message can be high. Presumably, that’s why my predecessor Alan Greenspan once told a Senate committee that, as a central banker, he had “learned to mumble with great incoherence.”

So we made one decision today, and that decision was to lower the federal funds rate by a quarter percentage point. We believe that action is appropriate to promote our objectives, of course. We’re going to be highly data-dependent. As always, our decisions are going to depend on the implications of incoming information for the outlook.

What a difference a few years make. Under Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen, and now Jerome Powell, the Fed has helped to deliver an economy with record low unemployment and near 2 percent inflation, just shy of its self-defined price stability target. But low growth, low inflation, and low interest rates—coupled with challenging policy and political environments—threaten the Fed’s capacity to autonomously extend the current, record-long expansion. These developments leave the Fed exposed to damaging attacks from the president and lawmakers, especially if or when the economy sours.

In October 2019, Federal Reserve Board Vice Chairman Richard Clarida reflected on the impact of these headwinds on the Fed’s approach to monetary policy and observed:

Looking ahead, monetary policy is not on a preset course, and the [Federal Open Market] Committee will proceed on a meeting-by-meeting basis to assess the economic outlook as well as the risks to the outlook, and it will act as appropriate to sustain growth, a strong labor market, and a return of inflation to our symmetric 2 percent objective [Clarida 2019a].

His “meeting-by-meeting” remark suggests that the communications tools used by the Fed to set expectations for future monetary policy—transparency and forward guidance—are less effective in this sluggish, decade-long, postcrisis economy. With rates near the effective lower bound, conventional policy tools struggle to meaningfully raise inflation and inflation expectations, a serious breach of half of the Fed’s statutory mandate. What’s more, recent research reveals the difficulty in understanding the process that generates upside inflation pressure (Yellen 2019). Even the “workhorse” Phillips curve linking unemployment and wages struggles to explain low consumer price inflation. Absent a coherent and effective model to generate higher inflation, communication is harder still.

Most accounts attribute the Fed’s policymaking difficulties to the challenging economic environment. But the origins of the Fed’s dilemma lie in the realm of politics, not just economics. Congressional demands over the past half-century for ever greater transparency push central bankers to justify their policy intentions to their Capitol Hill bosses. But meeting lawmakers’ expectations is difficult, if near impossible, when hyperpartisan politicians and the president send conflicting signals about how the Fed should deploy the tools in its arsenal. What’s more, important economic and political relationships have frayed, compounding the Fed’s difficulties in communicating its policy plans. Retrenching transparency, however, is rarely an option, snarling the Fed in a communications “trap.”

Has the central bank’s communication toolkit passed its “sell by date”? If so, why? Or does the current political economy simply require the Fed—assuming it secures political support—to reengineer those tools just a decade after the Fed last honed them in the wake of the financial crisis? In this article, we examine the economic and political roots of the Fed’s contemporary focus on communication, a component of standard monetary policymaking in which “open mouth policy” plays a key role in setting public, political, and financial market expectations for future policy. We explore how the breakdown of economic rules and political norms threatens the efficacy of Fed communications, especially affecting adoption of the Fed’s inflation target and the implementation of its balance-sheet policy. We conclude by considering the political constraints faced by the Fed as it considers revamping its communications given the institution’s tenuous position at the center of a polarized political system.

Economic and Political Roots of Fed Communication

Why does the Fed today care so much about communicating its intentions to markets, businesses, households, and the public? Economists and political scientists proffer different explanations. For students of macroeconomics and financial markets, central bankers were historically remiss to make plain their policy rationale and decisions. At the start of the 20th century, Montagu Norman (governor of the Bank of England between the world wars) best summed up the attitude when he reportedly offered the maxim, “Never explain, never excuse.” Decades later, Fed chairman Alan Greenspan (1988) famously remarked:

Since I became a central banker, I have learned to mumble with great incoherence.… I might add that on the issues of foreign exchange and interest rates this evening, if you think what I said was clear and unmistakable, I can assure you you’ve probably misunderstood me.1

Up until the mid-1990s, the Federal Reserve offered no post-meeting summary of its interest rate decision. Instead, market participants had to infer a policy change from postmeeting open market operations. For decades, central bankers reasoned that transparency made policy less, not more, effective: opacity limited markets from overreacting to the details of Fed decisions and protected the Fed’s discretion to change policy in light of economic developments (Yellen 2013).

Since Greenspan’s tenure at the Fed, of course, there has been a “revolution” (Yellen 2013) in central bankers’ attitudes toward transparency. Economists credit macroeconomic theory for providing a rationale to bolster Fed communications with businesses, markets, and the public. Especially when interest rates are close to zero, central bankers believe they can influence longer-term rates by shaping public expectations about the course of monetary policy. As Bernanke (2002) explains, if investors, businesses, and the public expect rates to be held low into the future, economic decisions can capitalize on that guidance and lower longer-term rates—thus stimulating demand and growth. As always, but especially with rates near the effective lower bound, the Fed’s influence on the economy depends directly on its ability to shape expectations about the future. And clear guidance about future policy decisions helps that effort. As Yellen (2013) describes the revolution, the Fed “journeyed from ‘never explain’ to a point where sometimes the explanation is the policy.” Or as Bernanke (2015a) put it, monetary policy is “98 percent talk and two percent action.”

Focusing exclusively on the economic origins of Fed communication, however, misses the equally important political roots of and motivation for heightened Fed transparency. Communications are a critical part of central bankers’ efforts to meet legislators’ demands for greater transparency. Lawmakers value transparency for two reasons. First, transparency offers a political mechanism for members of Congress to hold the central bank accountable for its performance in meeting the mandates cemented in the 1977 Federal Reserve Reform Act: maintaining low and stable prices and maximum sustainable employment. Second, transparency empowers politicians to blame the Fed when things go wrong. A recurring, countercyclical political dynamic drives lawmakers to impose new transparency demands on the Fed (Binder and Spindel 2017). In the wake of economic downturns when lawmakers blame the Fed for the economy’s poor performance, Congress often reopens the Federal Reserve Act to impose new requirements on the Fed, challenging central bankers to explain their policy decisions, how they are using their tools, and their process for making policy. The more Congress understands central bankers’ policy choices and projections, the easier it is to blame them when the economy sours. Of course, the same dynamic holds for the executive branch: The more the president knows about the future path of monetary policy, the easier it is to demand self-serving policy choices or to blame the Fed when (or if) things go south. In short, words and legislative/presidential pressure for greater transparency are rarely motivated by optimal economics.

Believers in central bank independence will question whether congressional demands for transparency shape Fed policy choices and tools. But the political roots of Fed transparency have the potential to constrain monetary policymakers. To be sure, institutionally the Fed is insulated from the rest of the government. Its funds come not from Congress but from its own operations, and Fed governors have extraordinarily long terms. But from inception to its current role as the most important economic policymaker in the world, the Fed faces pressures not only from lawmakers but also from presidents, bankers and the banks, the public, and global markets. Fed officials inevitably need to balance political pressures (and motives) against what they view as optimal monetary policy. Why? Because the threat of legislative action affecting the Fed—whether to impose new responsibilities or clip the Fed’s wings and tools—can discipline the Fed to heed both formal and informal congressional demands. The Fed can rarely risk getting out of step with the public or lawmakers, because Congress can revise the Federal Reserve Act to change the Fed’s mandate, its powers, or its responsibilities.2 The Fed’s dependence on Congress of course is not a one-way street. At the same time, Congress relies on the Fed to fulfill its mandate and to take the blame when the economy sours, making the two institutions interdependent.

Politicians can bring about greater transparency from the Fed in at least three ways: writing new mandates into statute, threatening to legislate if the Fed fails to act, or jawboning the Fed (particularly from the president’s bully pulpit).3 These pressures create incentives for the Fed—or can force it—to communicate more clearly to Congress, the public, and financial markets. Politicians do not always get what they want from the Fed. But neither can central bankers simply ignore political pressure. Indeed, however applied, pressure creates incentives or mandates for Fed officials to communicate more clearly and broadly. Below, we briefly review two such interactions between Congress and the Fed that drove key expansions in Fed transparency despite resistance from the Fed chair.4

Consider first the origins of the Fed’s macroeconomic objectives: revisions to the Federal Reserve Act in the mid-1970s that imposed audits on the Fed required the Fed chair to testify twice a year before the Fed’s House and Senate committee overseers and cemented the Fed’s dual mandates, among other changes. Congress and the president imposed these goals after years of interactions between Fed chair Arthur Burns and House Banking Committee chair, Rep. Wright Patman (D‑Illinois). As revealed in an exchange of letters between Burns and Patman that began in April 1975, Patman asked Burns to share verbatim transcripts for several years’ worth of recent FOMC meetings (Lindsey 2003: 11–15). Burns, unwilling to disclose the committee’s monetary policy deliberations to his congressional bosses, declared that the committee routinely disposed of verbatim records. After more fruitless exchanges, Burns and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) declined to provide any materials, arguing that disclosure would inhibit their policy deliberations.

But Patman and his banking committee successors held the upper hand. Over the next several years, a Democratic Congress backed by President Carter amended the Federal Reserve Act and other statutes to require increasing degrees of transparency from the Fed. With inflation at 10 percent and unemployment at its highest level since the Great Depression, amid an 18-month-long recession, lawmakers’ power to open up the Federal Reserve Act endowed Patman and his colleagues with critical leverage over the Fed. Long before the communications revolution in monetary theory that would later encourage the Fed to communicate clearly with its multiple audiences, congressional pressure forced the Fed to accommodate lawmakers’ demands for greater transparency.

Legislators’ threats can also compel the Fed to communicate its actions more clearly to Congress, markets, and the public. Starting in 1994, Greenspan greenlighted the release of the FOMC’s post-meeting statement, adding increasing details over time. In 1995, the Fed began releasing transcripts of past FOMC meetings (with a five-year lag). Fed officials took these steps not because they thought greater communication would contribute to better monetary policy. Greenspan and the committee acquiesced to greater transparency because the chairman of the House Banking Committee, Rep. Henry Gonzales (D‑Texas), threatened to revise the Federal Reserve Act and require the release of FOMC transcripts and videos within 60 days of each meeting.

Here, we briefly review a multiyear showdown that began in 1992 between Gonzales and Greenspan. Once again, congressional Democrats pushed the Fed to disclose verbatim transcripts of FOMC deliberations, asking whether public release would impair the Fed’s capacity to make sound policy (Auerbach 2006). But in congressional testimony in 1993, Greenspan denied that the Fed held any permanent electronic record of their discussions. It took some time for Greenspan to admit that the FOMC retained written transcripts, claiming that records existed for meetings beginning in early 1976. That acknowledgment undermined Greenspan’s strategy of dealing with Congress. With the House ratcheting up its threat to make timely release of transcripts and videos of each meeting, Greenspan and the FOMC relented and began to implement postmeeting statements and lagged release of the transcripts.

This back-and-forth reveals the interdependence of Congress and the Fed. It took years for lawmakers to determine that the Fed kept verbatim records of FOMC deliberations. Similarly, Greenspan and the FOMC members only slowly came to appreciate how serious Gonzales was about compelling near-immediate release of FOMC records. Small concessions summarizing past meetings would hardly suffice in face of lawmakers intent on mandating sweeping changes to Fed communications. A credible threat to legislate was both necessary and sufficient to compel the Fed to communicate with greater clarity and transparency about its current (and past) policy choices.

Viewed from the vantage of interdependence, the political basis for Fed transparency has implications for Fed communication strategies and tools. First, because the Fed is required to reveal its policy plans to Congress, the expectation of transparency limits the Fed’s ability to retrench its communications. The Fed has to tell Capitol Hill what it is up to, even if central bankers find it difficult—for economic or political reasons—to forecast where they see policy headed. That, no doubt, is why Bernanke’s first advice to Yellen for interacting with lawmakers was to remind her that “Congress is the boss” (Binder and Spindel 2017).

Second, Congress’s demand for transparency can constrain the range and shape of communications tools available to the Fed. This dynamic has played out in recent years when Republican lawmakers leaned on successive Fed chairs to commit to reducing the Fed’s balance sheet (still bloated with trillions of dollars of assets purchased in the wake of the financial crisis).5 As recently as November 2018, “some” FOMC members considered whether sticking with their commitment to shrink their assets might “demonstrate the Federal Reserve’s ability to fully unwind the policies used to respond to the crisis and might thereby increase public acceptance or effectiveness of such policies in the future” (FOMC 2018a: 3). At the same time, Democratic lawmakers have weighed in on the liability side of the Fed’s large balance sheet, particularly bank reserve balances, on which the Fed pays interest. Yellen was asked to “explore the alternative approaches that may exist that … does [sic] not rely so heavily on paying massive sums to private sector banks” (United States Congress 2016). More than economics and bank liquidity needs shape communications, and thus policy, about expected balance sheet size. Because influential lawmakers (namely, pivotal committee leaders) care about the Fed’s financial footprint, political (or as Fed officials seem to prefer to call them, “public”) concerns matter in shaping Fed communications about this elemental policy tool.

Economic and Political Threats to Fed Communication

Both economic and political pressures complicate effective monetary policymaking today. In both spheres, models that influence monetary policymakers appear to be fraying. The Phillips curve, the Fed’s inflation target, balance-sheet adjustments, low rates, and other features of contemporary monetary policy seem less reliable guideposts for central bankers than they were in the past. Given today’s economy, Summers and Stansbury (2019) even question whether or not interest rates are still useful for stimulating economic growth. Political norms are also under fire by a White House unrestrained by prior presidential policy of “hands off the Fed” and by polarized partisanship that often sends conflicting signals to the Fed about appropriate policy. We review these twin economic and political developments, and then turn in the next section to consider their implications for the effectiveness of the Fed’s communications arsenal.

Economic Challenges

Very low interest rates and a weakened relationship between growth and inflation present primary challenges for the Fed. To be sure, a combination of factors has depressed the Fed’s estimate of the neutral rate—that is, the policy rate that keeps the economy in equilibrium. But regardless of its causes, a declining neutral rate is problematic for the economy and for central bankers. As Clarida (2019b) explains, the lower the neutral rate, the more likely (all else equal) interest rates will reach the effective lower bound in future economic downturns. That in turn, Clarida warns, “could make it more difficult during downturns for monetary policy to support spending and employment, and keep inflation from falling too low” (Clarida 2019b). Unless elected officials are willing to provide sufficient fiscal stimulus during the next downturn, monetary policy, on its own, could be woefully inadequate.

At the Fed’s annual Jackson Hole conference in 2018, Chair Powell outlined these broader policy challenges by asking two key questions (Powell 2018). First, with the unemployment rate “well below the estimates of its longer-term normal level,” why wasn’t the FOMC contemplating more aggressive monetary tightening to “head off inflation”? Second, and paradoxically, “with no clear sign of an inflation problem, why is the FOMC tightening policy at all”? In the past, the Fed’s Phillips curve approach would measure more obvious tradeoffs between wages and unemployment and then consider how wage inflation translates into overall prices. But inflation, Powell argued, was sending “a weaker signal” on the back of successfully “anchored inflation expectations and the related flattening of the Phillips curve.”

Here is the dilemma for monetary policymakers: A low unemployment rate alone might no longer indicate a tight labor market. Thus, even with economic outcomes near the Fed’s congressional mandates, the economy no longer conforms to Fed expectations. Low unemployment often generates higher inflation. Growth below trend should put upward pressure on unemployment. As Powell reveals, these developments complicate estimates of macroeconomic speed limits, which are vital for calibrating monetary policy. In other words, is the Fed’s current policy stance stimulative or constraining?

A year later, in his semiannual congressional testimony, Powell was clear: “The relationship between the slack in the economy or unemployment and inflation was a strong one 50 years ago … and has gone away” (Powell 2019b). In recent high-profile speeches and additional congressional testimony, Powell admits that one could easily argue for tighter or looser monetary policy—given the dimming of the Fed’s past navigational stars and the weakening of its workhorse macroeconomic model. As we explore below, given these economic developments, central bankers have mostly mothballed the Fed’s postcrisis policy tool of forward guidance. Setting market expectations of future policy is near impossible in light of the Fed’s uncertainties.

Political Challenges

As the Fed grapples with vexing macroeconomic challenges, it operates under abnormally intense political pressure—particularly from President Donald Trump. Political attacks on the Fed are not new, neither from presidents nor lawmakers. But political pressure from legislators comes with the territory: Congress created the Fed, and as Paul Volcker once put it, “Congress can uncreate us” (Greider 1989: 473). Such pressure was understandably especially intense in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, when Congress amplified attacks on the Fed from populist movements on both the far left (“Occupy the Fed”) and right (“End the Fed”). But Fed officials expect lawmakers to criticize their conduct of monetary policy, especially when the economy is weak. Notably, legislators are more likely to threaten to sanction the Fed when unemployment, not inflation, rises (Binder and Spindel 2017: chap. 2). Moreover, with unemployment at a record half-century low today, lawmakers have turned down the temperature in their interactions with the Fed.6

Not so for President Trump. For the past 25 years, presidents have mostly restrained from directly and publicly criticizing the Fed. But Trump routinely castigates the Fed for insufficiently dovish policies—even though the Fed paused its three-year tightening campaign in January 2019 and began cutting rates that July. Via tweets or comments from the White House driveway, President Trump’s central bank broadsides run the gamut from caustically attacking Chairman Powell to exhorting the Fed to cut rates. Since the president took office in January 2017, he has assailed Powell or the Fed’s performance on Twitter more than 80 times, with the frequency increasing over the course of the 2019 reversal.7 “Bonehead” Fed officials are often “clueless,” or worse, such as when Trump (August 23) tweeted “My only question is, who is our bigger enemy, Jay Powell or [China’s] Chairman Xi?”8

Trump is not the first president to pine for electorally valuable monetary accommodation. Past presidents have certainly pushed—literally, in the case of President Johnson (Bremner 2004)—Fed chairs to lower rates to bolster economic growth. Episodes of presidential pressure appear in Arthur Burns’s diary in recounting his interactions with President Nixon (Ferrell 2010). News stories in the early 1960s report President Kennedy’s public statements on interest rates. And the New York Times gave above-the-fold coverage to President Johnson summoning Fed chairman William McChesney Martin down to the LBJ ranch late in 1965 to take him to the woodshed (literally) over rate hikes (Semple 1965). But the expectation that presidents would keep their “hands off the Fed” took root publicly early in the Clinton administration after Greenspan convinced the president to restrain from openly commenting on monetary policy (Mallaby 2016: 424–26). Clinton’s forbearance did not stem from a principled commitment to Fed “independence.” Instead, in concert with Clinton’s Treasury secretary, Lloyd Bentsen, and National Economic Council director, Robert Rubin, Greenspan eventually convinced Clinton that reducing the deficit—not pressuring the Fed—would help engineer a recovery from the 1991 recession. Clinton’s ambition to win reelection better explains the onset of the practice than a newfound respect for norms.

Unrestrained by precedent, President Trump ignored prior “hands off the Fed” protocol. And so the Fed today operates under both broken economic and political rules, exposing the Fed on both dimensions. The president’s economic policies—especially the imposition of tariffs on myriad trade partners—compound those pressures as they generate stiff headwinds for the Fed to consider in setting rates. The president defies rules in multiple ways: conducting a trade war, attacking the Fed and its policy choices, and exerting procyclical pressure for more dovish policy. That combination—compounded by already low rates and an enfeebled Phillips curve—raises steep challenges for the Fed. If the Fed lowers rates even further, it looks co-opted by the president—undermining market and public trust in the credibility of the Fed. If the Fed resists rate cuts, it incurs the wrath of the president and risks overly tight money. In this context, the Fed seems to have put aside its communications toolkit and limited itself to meeting-by-meeting policy choices.

Communication Challenges

The Fed’s new political and economic environments complicate how Fed officials shape and deploy their communications toolkit. We see this vividly in the Fed’s use of two key tools: its formal inflation target and its balance sheet policy in the wake of the financial crisis. The economic rationale underlying the Fed’s use of these tools receives ample attention. Here, we focus on how the Fed’s need to secure political support shapes the Fed’s adoption and efforts to revamp its communications tools.

Targeting Inflation

Close observers often point to the FOMC’s January 2012 “Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy” as the origins of the Fed’s formal inflation target. The statement announced that the FOMC judged “inflation at the rate of 2 percent, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures, is most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve’s statutory mandate” (Board of Governors 2012). Notably, the statement made plain that “communicating this inflation goal clearly to the public” was essential for securing both sides of its dual mandate. In other words, communicating the existence of the 2 percent target to markets, businesses, and the public was itself an instrument of monetary policy. Keeping longer-term inflation expectations anchored would enhance the Fed’s ability to maximize employment. The Fed viewed formalizing and revealing the target integral for Fed communications. The target was both a goal (reflecting the Fed’s congressional mandate to secure price stability) and an instrument (a tool for anchoring 2 percent inflation expectations).

However, inflation targeting predates the 2012 statement. Discussion about an inflation target occurred nearly two decades before. Most importantly, previous deliberations routinely considered how Congress might react if the Fed announced a specific numeric target for inflation, especially given the Fed’s other objective to maximize employment. Concern about reactions from Capitol Hill was reasonable given the contentious legislative politics of the 1970s when Congress revised the Federal Reserve Act to crystallize the Fed’s dual mandate in law (see Binder and Spindel 2017: chap. 6).

Sensitivity to Congress is visible in 1996 when the Greenspan Fed debated the definition of price stability and which numeric target might best approximate that goal. Keep in mind that the discussions occurred in the wake of congressional fireworks over Greenspan’s begrudging acknowledgment that the Fed had been withholding verbatim transcripts from Congress. As we explored earlier, the Fed slowly became more transparent in that era—for example, releasing minutes and transcripts of FOMC (with long lags) and announcing changes in the federal funds rate target and rationale for policy action. But the communications revolution observed by Yellen (2012) was not yet underway. As such, Greenspan is clear during a July 1996 FOMC meeting that he had no intention of making public the Fed’s informal 2 percent definition of price stability. He cautioned his colleagues that formalizing an inflation target was not a decision that central bankers could or should make themselves:

I think the type of choice is so fundamental to a society that in a democratic society we as unelected officials do not have the right to make that decision. Indeed, if we tried to, we would find that our mandate would get remarkably altered [FOMC 1996: 67].

Minutes later, Greenspan was more blunt: “I will tell you that if the 2 percent inflation target gets out of this room, it is going to make more problems for us than I think any of you might anticipate” (FOMC 1996: 72). Disclosing the FOMC discussion about an inflation target could, in Greenspan’s thinking, expose the Fed to congressional efforts to revamp the Fed’s mandate. Greenspan also likely preferred not to bind the Fed to meeting a particular target since it would limit his discretion. Keeping markets and politicians in the dark arguably protected his own power as chairman. For either or both reasons, Greenspan in this period deemed staying mum on inflation targeting essential.

Bernanke saw things differently. He notes in his memoir that when he joined the board in 2002, he began encouraging his colleagues to consider a numerical inflation target (Bernanke 2015b). Still, it took the Fed a full decade to adopt a target. Why the delay? During the several years Fed officials debated whether to adopt a formal target, FOMC members were acutely sensitive to the political costs of failing to get Congress on board with its plan. Consider, for example, an FOMC debate in October 2006, when Federal Reserve Bank of Boston president Cathy Minehan, argued: “We do need to consider the likely interaction with the Congress as we set a target for one of our goals but not another.… What else might that interaction with the Congress provoke? The possibility for unintended consequences is clear” (FOMC 2006: 153). Two years later, Donald Kohn, Fed vice chairman, similarly advised his colleagues: “Having an inflation target won’t have any effect if it is repudiated by the Congress. As soon as we make it, it could have a negative effect” (FOMC 2008: 68).

In his memoir, Bernanke (2015b: 526–27) explains that the need to secure political support delayed formalizing a target. In January 2009, Bernanke consulted with Representative Barney Frank (D‑Mass.)—then chairman of the House Financial Services Committee—about adopting a target. Frank declared that he would oppose the change. According to Bernanke, Frank understood the policy logic favoring an inflation target, but also recognized the poor politics of adopting a target for only half the Fed’s statutory mandate in the midst of recession: “He [Frank] thought that the middle of a recession was the wrong time to risk giving the impression, by setting a target for inflation but not employment, that the Fed didn’t care about jobs.” With Frank opposed—and the financial crisis overwhelming Fed officials—Bernanke deferred formal adoption of an inflation target until unemployment had dropped significantly. By December 2010, Bernanke suggested to his colleagues that “I think we’re at a moment that if we wanted to do something like that, it would actually be welcomed by the political world” (FOMC 2010: 109). It took another year to get it done.

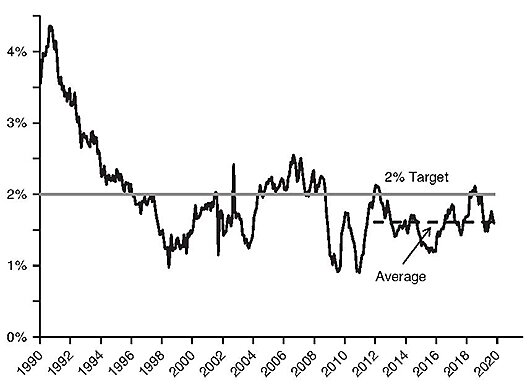

Most economists and Fed watchers would argue that the Fed’s inflation target worked well, anchoring inflation expectations appropriately. Others (including the current president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, John Williams) have suggested that the target might have worked too well (see Williams’s remarks in Brookings 2018: 10). Indeed, since adopting the 2 percent target in 2012, inflation (as measured by the Fed’s preferred core metric) has averaged only 1.6 percent (Figure 1).9

FIGURE 1: YEAR-OVER-YEAR CHANGE IN CORE (PCE) INFLATION (January 1990 to October 2019)

SOURCE: Bloomberg.

NOTE: Realized core inflation has averaged 1.6 percent since the Fed adopted its 2 percent target in January 2012.

Indeed, many argue that one solution to stubbornly low inflation would be to raise the Fed’s inflation target to 3 or 4 percent to telegraph the Fed’s desire for higher inflation (Blanchard, Dell’Ariccia, and Mauro 2010). Putting aside whether or not communicating a higher target would actually raise inflation, both Bernanke and Yellen argued against such a move. A key reason was Congress. As Bernanke observed in 2018:

The Federal Reserve is not going to adopt the 4 percent inflation target; it’s just not going to happen.… The political objection is that the U.S. public is not going to be very open to a 4 percent or 5 percent inflation target. In particular, I do worry that some of the people who are pushing this, so many of them are pro expansionists. They might find if they open this up too much, they’re going to end up with a change in the law that eliminates the employment goal rather than reasserts the price stability goal rather than what they’re hoping for (Bernanke as cited in Brookings 2018, 18).

Yellen (2018: 22), in turn, warned fellow central bankers that, absent congressional support, increasing the current target to raise inflation expectations would be “tricky business,” because Congress might consider it inconsistent with price stability. Powell, at his February 2019 post-FOMC meeting press conference (as cited in Cox 2019), took the hint: “We are not looking at a higher inflation target, full stop,” Current and former Fed chairs make plain that implementing a critical communications tool requires consent from Capitol Hill.

Balancing Act

Communication about policy—an essential element of the Fed’s toolkit for achieving its dual mandate—became especially difficult after the Fed lowered rates to near zero in the depths of the financial crisis. Unwilling to lower short rates below zero, the Fed tried to lower longer rates by dramatically increasing the size, composition, and complexity of its balance sheet. Such a strategy sparked criticism from both the left and right on Capitol Hill and exposed the Fed to numerous attacks from President Trump. These political pressures matter at least at the margins in shaping the Fed’s decisions about whether or not to shrink its balance sheet.

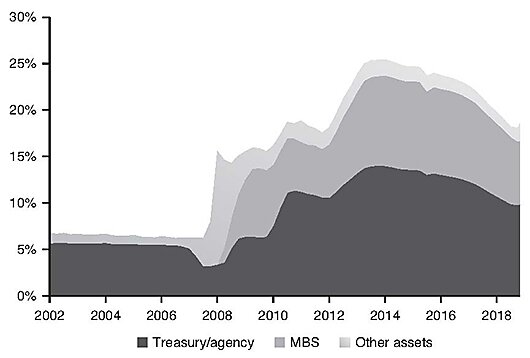

In the original Federal Reserve Act (1913), Congress authorized the purchase and sale of U.S. government bonds, empowering the Fed to expand and contract the money supply by adjusting its balance sheet. By statute, assets are required to be safe, typically government bonds. Standard accounting identities hold that when the Fed makes purchases, the balance sheet is equally inflated with central bank liabilities—that is, currency in circulation and bank reserves. Before the financial crisis, the balance sheet was a relatively small percentage of the economy; anodyne open market operations helped target the key federal funds rate. After the crisis, as Fed officials began to provide additional monetary accommodation by purchasing longer-term bonds and U.S. agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS), the balance sheet increased massively. Importantly, and by design, the maturity of the Fed’s assets became longer and less dominated by U.S. Treasuries. As shown in Figure 2, the balance sheet, at its peak, exceeded a quarter of the economy.

FIGURE 2: COMPOSITION AND SIZE OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE BALANCE SHEET, QUARTERLY, DECEMBER 2002 TO OCTOBER 2019 (Percent of GDP)

SOURCES: Bloomberg (GDP) and Federal Reserve H 4.1 Report.

The unconventional run-up in the balance sheet created political problems for central bankers. Legislators in the past have expanded and revised Section 14 of the Federal Reserve Act governing asset purchases. But in the wake of the financial crisis, politicians seemed to finally become aware of a range of issues associated with this new, old tool. Unlike straight-forward short-rate adjustments, the size, maturity, and makeup of the Fed’s balance sheet determine and complicate the efficacy of this blunt tool. As Fed officials adjusted and readjusted these parameters, they invited a range of critical questions from legislators attempting to shape and limit monetary policy.

One challenge for Fed officials posed by their balance sheet transformation is its sheer complexity. Asset purchases are just harder to calibrate and explain. For example, the Fed struggled to define their actions. Initially, they referred to the program as large-scale asset purchases (LSAPs), focusing attention on the U.S. Treasury bonds and MBS they were buying. Ultimately, the Fed adopted the market’s language and more traditional description, quantitative easing (QE). The nomenclature changes underscore the challenge. Was the Fed targeting liabilities (i.e., bank reserves) through QE or assets via LSAPs? What’s the distinction? Even Bernanke quipped about his unconventional efforts: “Well, the problem with QE is it works in practice, but it doesn’t work in theory” (Bernanke 2014: 14). Lack of conceptual clarity likely contributed to two misguided notions pushed by conservative Fed critics: first, purchasing U.S. government bonds on the open market was tantamount to debt monetization (which is forbidden under the Federal Reserve Act); and second, debt monetization leads to hyperinflation. A decade after the crisis with inflation still below target, both preconceptions appear to be false.

Key members of Congress continued to pressure the Fed years after the crisis. They questioned whether central bank bond purchases, particularly MBS, transforms broad monetary policy into targeted credit allocation and fiscal policy. To be sure, the housing-induced credit crunch compelled the Fed to buy MBS to put downward pressure on mortgage rates.10 But the policy’s success led Hill critics to accuse the Fed of picking winners and losers with quasi-fiscal policy. It was a tough charge for central bankers to refute. Congress had done relatively little to address the nation’s mortgage foreclosure crisis, even though losses from the catastrophic bust of the U.S. housing market helped to precipitate the financial crisis. Absent fiscal intervention from Congress, monetary policy was the only game in town.

Criticisms came first from the right. Jeb Hensarling (R‑Texas), the chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, warned then-Fed chair Janet Yellen that the large balance sheet raised the risk that “we may wake up one day to find our central bankers have instead become central planners” (CQ 2017: 2). Conservative members of Congress amplified their frustration with the Fed’s perceived allocation of credit, a key legislative responsibility. More obviously, these fiscal hawks saw the Fed’s large balance sheet enabling debt issuance, violating a key tenet of their ideology. Democrats, including the ranking member on the House Financial Services Committee, Rep. Maxine Waters of California, were equally agitated that the Fed’s large balance sheet policies created ample bank reserves, on which the Fed (authorized by Congress) was paying interest.11 For lawmakers on both sides of the aisle, the political optics of apparently subsidizing banks not to lend swamped rewards to the economy from the Fed’s expanding balance sheet.

Even a decade after the financial crisis, Fed officials still struggle with sizing the balance sheet. Central bankers continue to face multiple, often conflicting, signals from politicians at both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue. Consider the pressures confronting Powell from Capitol Hill. To help secure consent by a Republican-led Senate, Powell committed during his confirmation hearing in November 2017 to reducing the Fed’s footprint (U.S. Congress 2017: 5–6). Both parties criticized the Fed for paying interest to banks on their ample excess reserves held at the Fed, adding additional pressure to normalize the balance sheet. At the same time, lawmakers occasionally tap Federal Reserve profits (a partial by-product of large balance sheet policies) to help fund political priorities—including a multiyear highway bill in 2015 and a budget deal in 2018. Political pressure backed by congressional raids of the Fed’s capital accounts undermines the Fed’s autonomy and heightens risks posed in shrinking its balance sheet (Condon 2018). What’s more, lawmakers’ prescriptions for monetary (and fiscal) policy can change with congressional and presidential elections, scrambling the cues Fed officials receive from the Hill. In sum, powerful lawmakers still care about the Fed’s balance sheet and Federal Reserve officials are sensitive to those concerns.

Quantifying the economic, regulatory, and financial impact of the bloated balance sheet remains a challenge. This is especially so after recent developments in the Fed-assisted funding (or “repo”) market for U.S. government bonds led to an October 2019 FOMC decision to steadily increase the balance sheet by almost half a trillion dollars (Timiraos 2019a).12 Recent debates about “normalization” reveal Federal Reserve officials’ acute sensitivity to the public’s interpretation of the balance sheet’s size (see FOMC 2018a, 2018b). Reflecting that concern, Powell insists that this latest, unexpected increase in the size of the balance sheet “is not QE. In no sense is this QE.”13

Piling onto market frustration, President Trump added balance sheet wind-down to his list of Fed transgressions—demanding that the Fed stop tightening monetary policy via a smaller balance sheet. Just as FOMC members were gathering in December 2018, Trump tweeted:

I hope the people over at the Fed will read today’s Wall Street Journal editorial before they make yet another mistake. Also, don’t let the market become any more illiquid than it already is. Stop with the 50 B’s [basis points]. Feel the market, don’t just go by meaningless numbers.14

The Fed hiked rates, Powell remarked that balance sheet runoff was on “automatic pilot” (Board of Governors 2018), markets tumbled, and Trump reportedly considered firing Powell (Jacobs, Mohsin, and Talev 2018). The Fed paused its hiking campaign and wind-down of the balance sheet soon thereafter. In sum, more than economics and bank liquidity needs matter. Political as well as economic imperatives shape communications about this unconventional, if elemental, policy tool.

Conclusion

One thing we’ve discovered about communication policy is that, once you make changes, they are really hard to take back. So we need to get clear among ourselves what we are doing, why we are doing it, and what the implications are for our own deliberations, for our communication with the public, and for the material we might get from the staff for meetings [FOMC 2006: 124].

Kohn’s precrisis observation crystallizes Fed officials’ current communications dilemma. Economic theory reveals the enhanced potency of policy transparency, especially near the effective lower bound (Woodford 2005). Clarity often yields macroeconomic benefits by reducing uncertainty about the future. And the Fed’s multiple audiences crave policy commitments. Congress demands transparency from the Fed, so that lawmakers can hold the Fed accountable to congressional mandates and/or blame them for inevitable downturns. So do investors, businesses, and individuals, who want to know what to expect so they can plan accordingly.

The economic and political conditions that gave rise to a regime of forward guidance have evolved, ensnaring Fed officials in a communications trap, talking about policy “one meeting at a time.” Their favored tools, shaped partially by legislators, are losing their efficacy. At the same time, lawmakers and the president compete to push the process in their favor. These uncertainties sparked the Fed’s 2019 year-long introspection (dubbed “The Fed Listens” tour) to reconsider the Fed’s monetary policy strategy, tools, and communications (Timiraos 2019b).

The Fed’s current efforts to meet its inflation target, manage the balance sheet, and reduce uncertainty about the future illustrate the trap. Satisfying political demands for greater transparency dogs the Fed with potentially economically suboptimal communications strategies and complicated instruments. With record low unemployment and a procyclical fiscal boost, President Trump’s attacks on the Fed for failing to deliver ever-more accommodative policy—even after the Fed’s dovish turnaround—compound the Fed’s difficulties. The Fed’s legitimacy is at risk. As Greenspan (FOMC 1996: 82) defined that term over two decades ago, “the public has to have confidence that the Fed knows what it is doing.” Revamping its communications without losing public support remains a high bar for the Federal Reserve.

References

Auerbach, R. (2006) “The Painful History of Fed Transparency.” Marketwatch (May 8).

Bernanke, B. S. (2002) “Deflation: Making Sure “It” Doesn’t Happen Here.” Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke before the National Economists Club, Washington, D.C. (November 21).

___________ (2014) “Central Banking after the Great Recession: Lessons Learned and Challenges Ahead. A Discussion with Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke on the Fed’s 100th Anniversary.” Brookings Institution (January 14).

___________ (2015a) “Inaugurating a New Blog.” Brookings Institution (March 30).

___________ (2015b) The Courage to Act: A Memoir of a Crisis and Its Aftermath. New York: Norton.

Binder, S., and Spindel, M. (2017) The Myth of Independence: How Congress Governs the Federal Reserve. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Blanchard, O.; Dell’Ariccia, G.; and Mauro, P. (2010) “Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy.” IMF Staff Position Note (February 12).

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2012) “Federal Reserve Issues FOMC Statement of Longer-Run Goals and Policy Strategy.” Press release (January 25).

___________ (2018) “Chairman Powell’s Press Conference.” Transcript (December 19).

Bremner, R. P. (2004) Chairman of the Fed: William-McChesney Martin Jr. and the Creation of the American Financial System. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Brookings Institution (2018) Transcript Panel 1: The Options—Keep It, Tweak It, or Replace It. “Should the Fed Stick with the 2 Percent Inflation Target or Rethink It?” Brookings Institution (January 8). Available at www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/panel-1-transcript.pdf.

Clarida, R. H. (2019a) “U.S. Economic Outlook and Monetary Policy.” Speech delivered at the Fixed-Income Management Conference, “Late Cycle Investing: Opportunity and Risk,” sponsored by the CFA Institute and the CFA Society of Boston (October 18).

___________ (2019b) “The Federal Reserve’s Review of Its Monetary Policy Strategy, Tools, and Communication Practices.” Speech delivered at the U.S. Monetary Policy Forum, sponsored by the Initiative on Global Markets at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, New York (February 22).

Condon, C. (2018) “Congress Raids Fed’s Surplus for $2.5 Billion in Budget Deal.” Bloomberg News (February 9).

Cox, J. (2019) “Fed Chair Powell Says Balance Sheet Decision Market Is Waiting for Is ‘Close’ to Happening.” CNBC (February 27).

CQ (2016) “House Financial Services Committee Holds Hearing on Monetary Policy.” Congressional Transcripts. Final transcript (February 10).

___________ (2017) “House Financial Services Committee Holds Hearing on Monetary Policy with Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen.” Congressional Transcripts. Final transcript (July 12).

Davidson, K. (2019) “House Republican McHenry Asks for Details on Fed Balance-Sheet Operations.” Wall Street Journal (October 18).

Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) (1996) “Meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee” (July 2–3). Available at www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/FOMC19960703meeting.pdf.

___________ (2006) “Meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee” (October 24–25). Available at www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/FOMC20061025meeting.pdf.

___________ (2008) “Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee” (December 15–16). Available at www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcminutes20181216.pdf.

___________ (2010) “Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee” (December 14). Available at www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/FOMC20101214meeting.pdf.

___________ (2018a) “Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee” (November 7–8). Available at www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcminutes20181108.pdf.

___________ (2018b) “Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee” (December 18–19). Available at www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcminutes20181219.pdf.

Ferrell, R. H., ed. (2010) Inside the Nixon Administration: The Secret Diary of Arthur Burns, 1969–1974. Lawrence, Kan.: University of Kansas Press.

Gagnon, J.; Raskin, M.; Remache, J.; and Sack, B. (2010) “Large-Scale Asset Purchases by the Federal Reserve: Did They Work?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports. Staff Report No. 441 (March).

Greenspan, A. (1988) “Informal Remarks before a Dinner Meeting of the Trilateral Commission.” Washington, D.C. (June 23).

Greider, W. (1989) Secrets of the Temple: How the Federal Reserve Runs the Country. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Jacobs, J.; Mohsin, S.; and Talev, M. (2018) “Trump Discusses Firing Fed’s Powell after Latest Rate Hike, Sources Say.” Bloomberg News (December 21).

Lawler, J. (2016) “Key House Democrats Warm to Fed Payments to Banks.” Washington Examiner (May 17).

Lindsey, D. (2003) “A Modern History of FOMC Communication: 1975–2002.” Typescript. Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat. Available at https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/books/20030624_lindsey_modhistfomc.pdf.

Luciani, M., and Trezzi, R. (2019) “Comparing Two Measures of Core Inflation: PCE Excluding Food & Energy vs. the Trimmed Mean PCE Index.” FEDS Notes (August 2).

Mallaby, S. (2016) The Man Who Knew: The Life and Times of Alan Greenspan. New York: Penguin Press.

Miller, R., and Torres, C. (2018) “The Fight to Protect the Fed from Trump’s Rate-Hike Barbs.” Bloomberg BusinessWeek (September 20).

Powell, J. (2018) “Monetary Policy in a Changing Economy.” Speech delivered at “Changing Market Structure and Implications for Monetary Policy,” a symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyo. (August 24).

___________ (2019a) “Transcript of Chair Powell’s Press Conference” (September 18). Available at www.federalreserve.gov/mediacenter/files/FOMCpresconf20190918.pdf.

___________ (2019b) “Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee Holds Hearing on the Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to Congress” (July 11). CQ Transcripts.

Semple, R. B. Jr. (1965) “President Meets Martin at Ranch; They Talk 2 Hours.” New York Times (December 7): 1.

Summers, L. H., and Stansbury, A. (2019) “Whither Central Banking?” Project Syndicate (August 23).

Timiraos, N. (2019a) “Fed Will Purchase Treasury Bills at Least into Second Quarter of 2020.” Wall Street Journal (October 11).

___________ (2019b) “Clarida Outlines Scope for Fed Review of Interest-Rate Policy Strategies.” Wall Street Journal (February 22).

United States Congress (2016) House Committee on Financial Services, 2001–. “Monetary Policy Oversight: House of Representatives Hearings, 1978–2019” (February 10). Available at https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/672/item/553651.

___________ (2017) Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs. Nomination of Jerome H. Powell (November 28). S. HRG. 115–157. Available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-115shrg28661/pdf/CHRG-115shrg28661.pdf.

Woodford, M. (2005) “Central Bank Communication and Policy Effectiveness.” In The Greenspan Era: Lessons for the Fed, 399–474. Proceedings: Economic Policy Symposium, Jackson Hole, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City (August).

Yellen, J. L. (2012) “Revolution and Evolution in Central Bank Communications.” Speech given at the Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley, November 13.

___________ (2013) “Communication in Monetary Policy.” Address delivered at the Society of American Business Editors and Writers 50th Anniversary Conference, Washington, D.C.

___________ (2018) “A Fed Duet: Janet Yellen in Conversation with Ben Bernanke.” Brookings Institution (February 28).

___________ (2019) “Former Fed Chair Janet Yellen on Why the Answer to the Inflation Puzzle Matters.” Brookings Institution (October 3).

About the Authors

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.