In the decade since the global financial crisis, there has understandably been great concern about potential threats to global financial stability, and policymakers have wisely remained vigilant in watching for warning signs of possible economic risk. At the International Monetary Fund (IMF), we remain committed to providing our 189 member countries with farsighted analyses of trends in the financial markets, thus guiding them toward sound policy choices that help maintain economic stability.

Risks for the Global Economy

Global economic growth has remained strong, and the IMF’s latest analysis suggests that a global recession is not around the corner. However, as we look ahead, the risk of a decline in global growth has increased. Global financial conditions have tightened appreciably in the past few months of 2018, with a significant global sell off in many major financial markets in the last quarter of the year. While there has been a partial retracement of that sell off in 2019 — globally, markets are now looking for signs that the financial cycle may finally be turning. That is especially true in the United States, which has been further ahead in the economic and financial cycle compared to most other regions. In addition, investors are focused on the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), trying to judge whether the Federal Reserve may be close to ending — or at least pausing — its recent series of interest-rate hikes. Other key concerns include the slowdown in the Chinese economy, continuing trade tensions, and political risks such as Brexit.

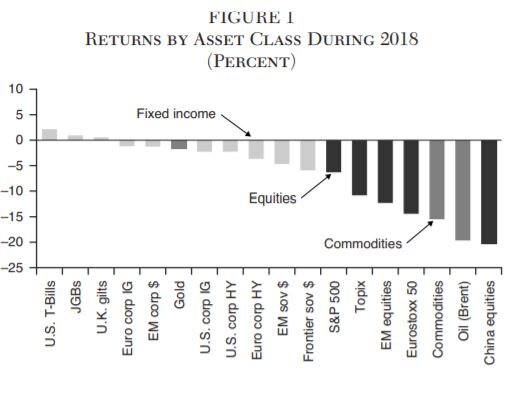

In fact, 2018 was the most difficult year for markets since the global financial crisis (Figure 1). Almost every asset class saw negative returns. The few major areas that showed positive results were “safe haven” assets such as U.S. Treasuries, U.K. gilts, and Japanese government bonds. Global financial markets also saw the return of significant volatility in 2018. The VIX index, which is often seen as a proxy for market anxiety, saw several spikes over the course of the year. Markets have recovered somewhat in the new year — with stocks making up about half of their 2018 losses, and with credit spreads tighter by about one-third.

The IMF’s Growth-at-Risk Approach

The tightening in financial conditions is important because it can have an impact on downside risks to growth. This relationship is encapsulated in the IMF’s Growth-at-Risk approach, which was first introduced in the October 2017 edition of our Global Financial Stability Report (IMF 2017).

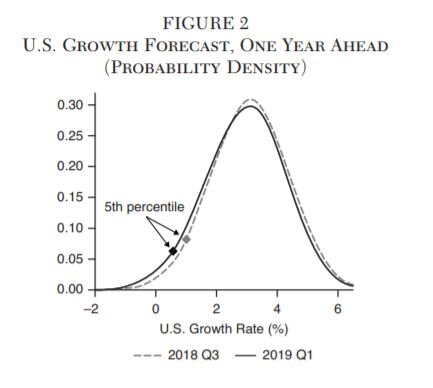

Using statistical techniques, we project a distribution of possible outcomes — which, in turn, helps us identify the most adverse scenarios located in the “left tail” of the distribution (with a 5 percent likelihood of occurring). Over time, we can track the changes in these 5 percent tail scenarios, and we can analyze how they respond to changing economic and financial conditions.

Running our growth-at-risk model for the United States, we find that risks to U.S. growth have increased somewhat. The distribution has moved slightly to the left compared to the third quarter of 2018, even after accounting for the partial retracement of the market selloff (Figure 2).

One key driver for the tightening of global financial conditions was the negative data surprises we saw in parts of the world in 2018. Eurozone economic data were weak; data from emerging markets were often disappointing; and even the strong U.S. economy began to show signs of a slowdown. Another important catalyst was a pessimistic season of “forward guidance” from corporate management — underscoring trade fears, political uncertainty (especially in Europe and the United Kingdom), rising labor costs, and slowing economies worldwide. In the United States, corporate earnings growth is projected to decline in 2019.

The Outlook for Inflation

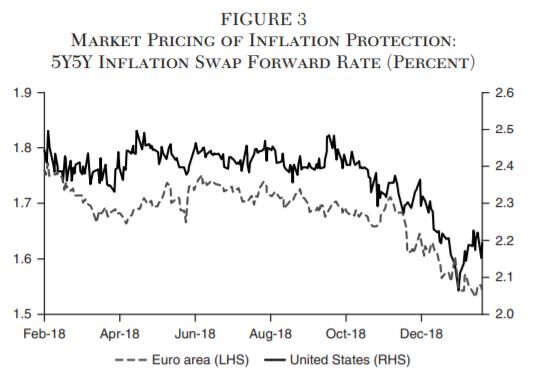

Together, these two trends led to lower market expectations for inflation. We can see this clearly when looking at inflation swaps, which are among the most important instruments for determining market inflation forecasts for the United States and the eurozone. In both regions, markets are predicting that inflation will remain subdued over the next five years (Figure 3). Options on inflation swaps allow us to estimate the implied probabilities for potential inflation outcomes in the future. These options suggest that inflation is likely to remain low with there being little chance of U.S. or eurozone inflation hitting 3 percent for a full year, over the next five-year period.

This outlook for inflation has led markets to expect a more dovish path for central banks. In the United States, markets now expect the Fed to stay “on hold” in 2019–20. By contrast, the current “dot plot” from the FOMC has a median forecast of two hikes in 2019. How these Fed projections and market forecasts are reconciled, will be one of the key questions for 2019. For the European Central Bank (ECB), markets predict the first hike in 18 months — up from 12 months as recently as October.

Signs of Late-Cycle Behavior

Meanwhile, many observers foresee that the end of the current financial cycle may be getting closer in the United States. A variety of economic and financial variables display late-cycle behavior. Although financial conditions are tightening, credit spreads are still narrow by historical standards, and M&A activity has been strong — a factor that we often see near the end of cycles. The yield curve has begun to flatten — a process that tends to occur before the onset of a downturn. Corporate margins may have peaked; wage growth is picking up; and unemployment is very low.

There are additional signs of late-cycle behavior, especially in the U.S. bond market. Term premia and credit spreads are compressed today, as they usually are near the end of the cycle. In addition, bond markets may be underpricing credit risk. Probabilities of default, calculated using widely used models, are very low despite a much higher level of corporate debt. Easier financial conditions lead to lower default forecasts in these models, causing investors to tolerate higher credit risk. That is when credit problems tend to build up in markets.

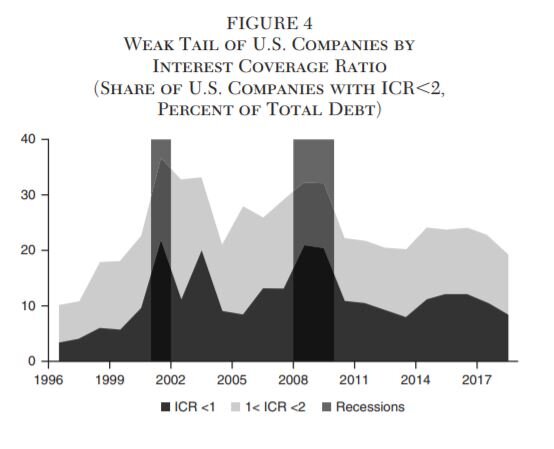

A deterioration in corporate credit quality is a growing concern among market participants, as well as among regulators. In some countries, corporate debt levels have spiked in the decade since the global financial crisis, and they have remained high in other major markets (see Adrian 2018). The increasing issuance of lower-rated debt, with fewer covenants or other investor protections, has led to heightened scrutiny by the Federal Reserve, European regulators, and others. Weaker corporate credit could become a major problem if forecasts of lower earnings turn out to be correct. The weak tail of corporations, whose earnings are only just high enough to cover their interest costs, could become vulnerable to default if the economy slows down and if their earnings become insufficient to service their debt (Figure 4). This weak tail could grow larger if the downturn is severe, as it did in the United States in 2000 and in 2008.

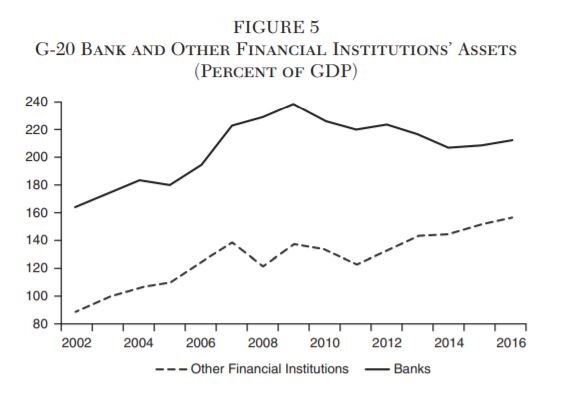

Moreover, the nonbank financial sector has come to play an increasingly important role in the provision of credit, as banks have reined in their lending due to competitive pressures, regulation, and other factors (Figure 5). As a result, the market for leveraged loans has grown significantly worldwide — and, remarkably, in the United States it is now larger than the high-yield bond market (Adrian, Natalucci, and Piontek 2018). Collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) and loan mutual funds now play a dominant role in the leveraged loan sector. Private equity, hedge funds, and pension funds also have a large footprint in nonbank lending, both through CLOs and direct loans. Worries about credit quality made 2018 a bumpy year for U.S. credit markets. There were major episodes of investor selling during the year, and December was the first month in a decade where there was no issuance in the U.S. high-yield market.

Policymakers have limited means to take remedial action in nonbank lending, even as credit quality deteriorates. Liquidity and maturity mismatches among asset managers are a significant concern. With banks no longer willing to provide liquidity, a flood of investor redemptions could lead to significant market dislocations if asset managers need to sell. Today, much of the nonbank sector remains uncovered by macroprudential policies. Few policy tools are now available, because some only apply to money-market funds rather than the wider set of investment funds. Authorities should explore a wider range of macroprudential measures to address these issues.

Emerging markets have also been affected by the market selloff. Portfolio inflows fell, although they have come off their lows in recent weeks. Rising spreads and higher volatility have caused emerging market and frontier issuers to face higher funding costs and lower investor demand.

China and Europe

China remains front-and-center for global financial markets, with a great deal of focus on the health of the economy and the tariff dispute with the United States. Volatility in Chinese markets could have a negative impact on other emerging markets. The correlation between Chinese stocks and other emerging-market equities has been rising since trade tensions flared up last year. Another area of vulnerability for emerging markets is a stronger dollar, because emerging-market corporates ramped up their dollar borrowing in recent years to take advantage of low funding costs.

China’s stock market was the worst-performing major market in 2018, as trade tensions flared up amid regulatory tightening. Stocks with significant U.S. exposure were especially hard hit. Although the authorities have introduced measures to ease conditions, funding costs did not fall appreciably, perhaps due to lenders’ concern about the creditworthiness of corporate borrowers. This year, the authorities have introduced several additional measures to ease conditions, and local markets have started the year on a modestly positive note.

Turning to Europe, Brexit-related uncertainty remains very high. U.K. stocks have significantly underperformed global equities over the past few years. Volatility in the sterling foreign-exchange options market has spiked, and the demand for protection against depreciation grows, especially around key risk periods such as the run-up to Brexit.

In Europe, another risk facing investors is the “sovereign-bank” nexus. This is the negative feedback loop that builds up when banks face problems because of the credit woes of their home countries. Banks typically have large holdings of government bonds issued by their home countries, but these bonds lose value when markets begin to worry about the home country’s credit risk. An escalation of credit-related worries about a country leads to an escalation in credit risk for the banks themselves.

Italy was in the spotlight for much of the year amid the budget standoff with the European Union, given its banks’ large holdings of Italian government securities, or “BTPs.” Yield spreads between BTPs and German bunds flared up in the summer, and they have yet to fully recover, while Italian equities underperformed at the height of the tension.

Summary

To summarize what I have outlined: global financial conditions tightened in the fourth quarter of 2018, on the back of a correction in corporate valuations. They saw a partial retracement in early 2019, with equities recovering about half of their losses, and with credit spreads tightening by about one-third. But global conditions are still tighter on net.

Moreover, the data suggest that the financial cycle in the United States could be approaching its end. Other key risks on the horizon include additional weakening in economic activity, a further tightening of financial conditions, trade policy concerns, and political risks as exemplified by the Brexit issue.

At the IMF, we are committed to monitoring global financial trends very carefully, aiming to help national authorities shape sound policies that protect against financial vulnerabilities. As we approach our spring meetings in April, when we will publish the next edition of our Global Financial Stability Report, we are continuing to study global financial developments very closely, remaining watchful for any factors that could put economic growth at risk.

References

Adrian, T. (2018) “The Financial System Is Stronger, but New Vulnerabilities Have Emerged in the Decade Since the Crisis.” IMFBlog (October 9). Available at https://blogs.imf.org/2018/10/09/the-financial-system-is-stronger-but-new-vulnerabilities-have-emerged-in-the-decade-since-the-crisis.

Adrian, T.; Natalucci, F.; and Piontek, T. (2018) “Sounding the Alarm on Leveraged Lending.” IMFBlog (November 15). Available at https://blogs.imf.org/2018/11/15/sounding-the-alarm-on-leveraged-lending.

IMF (International Monetary Fund) (2017) Global Financial Stability Report: Is Growth at Risk? (October). Washington: International Monetary Fund. Available at www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2017/09/27/global-financial-stability-report-october-2017.