The internationalization of China’s currency, the Renminbi (RMB) or yuan, has accelerated since the global financial crisis. On the one hand, the rate at which China is overtaking the United States as the largest economy in the world sped up because of the lingering effects of the crisis on U.S. growth and the fact that China weathered the crisis very well. On the other hand, global and Chinese confidence in the dollar and U.S. financial institutions was seriously undermined by the crisis. China’s central bank governor, Zhou Xiaochuan, wrote an article in 2009 criticizing the dependence of the world on the dollar and launching a period in which China actively promoted the internationalization of its currency (Zhou 2009).

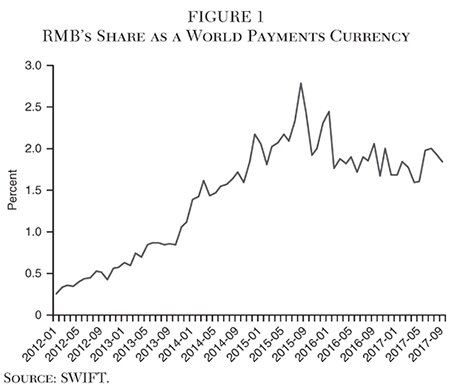

Initially there was steady and rapid increase in measures of internationalization, such as the RMB’s share in global payments (Figure 1). However, the growth came to an end in the middle of 2015, and since then China’s share has declined modestly. There was also an expectation that China’s growing role as a source of development finance would enhance the importance of the RMB. China in the period 2012–14 lent about $40 billion per year to developing countries for infrastructure projects, including along the Belt and Road, according to updated AidData (Dreher et al. 2017). Curiously, most of this lending is in dollars and only 2.6 percent was denominated in RMB.

How do we understand the stalled progress in the emergence of the yuan as a major currency? China’s prospects to be the largest economy in the world in about 10 years have not changed. But other factors that are relevant for reserve currency status are coming increasingly into play. Prasad (2015) identifies several factors that are relevant to reserve currency status, in addition to market size: open capital account, flexible exchange rate, macroeconomic policies, and financial market development.

In addition, there is a significant literature relating financial market development and macroeconomic policies to underlying institutions such as property rights and rule of law and open political institutions. At the moment, China has institutional weaknesses that hamper its emergence as a major reserve currency country. It also has limitations on capital account openness and exchange rate flexibility that are more in the nature of short-term impediments.

The next two sections focus on (1) the institutional weaknesses that are long-term impediments and (2) the current situation with macroeconomic policies, the capital account, and the exchange rate. It is not surprising that the initial enthusiasm over RMB internationalization has waned to some extent: China is a long way from meeting the conditions to be a major reserve currency country.

Evolution of Institutional Quality in China

The issue of institutional quality in China presents something of a puzzle. In general, we think that economic institutions such as property rights and the rule of law are fundamental to long-run growth (Acemoglu, Johnson, and James 2001). However, China appears to have rather poor institutions, and yet has grown at about 10 percent per year for four decades. One resolution of this paradox is to think of institutions relative to development level. China emerged from the Mao era and the Cultural Revolution as one of the poorest countries in the world, poorer than Sub-Saharan Africa. It began its economic reform under Deng Xiaoping with a series of institutional reforms that dramatically increased incentives to invest and produce: the household responsibility system that restored family farming, opening of a growing number of cities to foreign investment and trade, and legalization of private firms (Eckaus 1997). Unfortunately, there are no consistent measures of institutional quality from this early era, but the basic picture emerges from an examination of data from the mid-1990s.

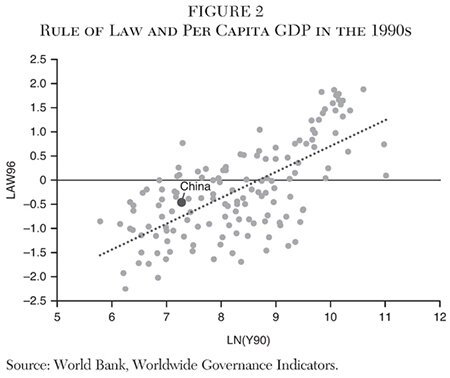

Empirically, there are a number of options for measuring economic institutions. I prefer the Rule of Law Index from the World Governance Database, which “captures perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence.” The index, which has a mean of zero and standard deviation of 1.0, is available for a large number of countries.

In general, measures such as the Rule of Law Index rise with per capita GDP, though in fact the fit is not that tight and there is a lot of dispersion (Figure 2). Most developing countries have below-average institutional quality, but, as noted, there is large dispersion. Figure 2 illustrates Rule of Law 1996 (first year available) and log per capita GDP in 1990.

China was measured to be about half a standard deviation below the mean on the index: it did not have especially good economic institutions. However, it was above the regression line, indicating that it had good institutions for its level of development. Another way to express this is that China’s Rule of Law Index in 1996 was at the 45th percentile among countries. Its per capita GDP in 1990 was at the 23rd percentile among countries.

Think of China competing with other low-income countries in the early 1990s to attract foreign direct investment (FDI), generate exports, and begin the growth process. It was a very low-wage economy. Among the countries with which it was competing, China proved to be an attractive production location and subsequently grew well. A poor country that can manage to put reasonably good institutions in place has all of the convergence advantages: it can attract FDI, borrow technology from abroad, and start the catch-up process.

Thinking about institutions relative to level of development naturally leads to some questions: Are institutions keeping up? Is there regular institutional improvement as the economy develops? For China, the answer is basically, “no.” China’s per capita GDP has grown enormously: by 2016 it was at the 58th percentile of countries for per capita GDP in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms. Its rule of law ranking, on the other hand, has barely changed over time and in 2016 was at the 46th percentile. Over 20 years there has been no measurable improvement. China’s reform program has stalled (Naughton 2014), and now it has poor economic institutions for its level of development.

What about the relationship between political institutions and economic institutions? Acemoglu and Robinson (2012), in their book Why Nations Fail, emphasize the link from political institutions to economic institutions to outcomes. In their model, countries with democratic political institutions tend to develop inclusive economic institutions, which, in turn, lead to innovation and productivity growth, and, hence, sustained improvements in living standards.

An alternative view these days is the “Beijing consensus” model: democratic countries seem incapable of making the difficult decisions and investments needed to sustain prosperity, whereas an authoritarian “developmental” state is capable of operating more efficiently.1 Huntington (1968) offers something of an intermediate argument—namely, that premature increases in political participation, including early elections, could destabilize fragile political systems. His argument laid the groundwork for a development strategy that came to be called the “authoritarian transition,” whereby a modernizing dictatorship provides political order, rule of law, and the conditions for successful economic and social development. Once these building blocks were in place, other aspects of modernity like democracy and civic participation could be added. What does the evidence from the past 20 years suggest about this debate?

To measure political institutions, I use Freedom House’s Civil Liberties Index.2 Freedom House also has a Political Rights Index that focuses on democratic political institutions. I prefer the Civil Liberties Index that measures aspects such as freedom of speech, the media, assembly, and association. In practice the two series are highly correlated and will not produce different empirical results. I prefer the Civil Liberties measure because I think of it as more closely connected to the environment for innovation and competition—that is, the economic institutions.

The Civil Liberties Index is available for a large group of countries starting in 1994. It ranges from 1 (completely free) to 7 (completely unfree). Among the poorer half of countries in the world, there is little correlation between economic institutions and political institutions (correlation coefficient equals −0.33). I have already highlighted that authoritarian countries such as China had relatively good economic institutions among poor countries in the 1990s. Vietnam would be another example, as would South Korea and Taiwan in an earlier era. The latter two are the best examples of economies that made the transition to political openness in middle income. Among the richer half of countries, on the other hand, there is fairly high correlation (−0.67) between political freedom and rule of law. There are few historical cases of achieving truly strong property rights and rule of law without political openness.

China so far is not following the path of political liberalization as it transits through middle income. The civil liberties measure for China has remained at 6 for a long time. Xi Jinping has made it clear that he wants to pursue economic reform without political reform.3 Not only has there not been political reform, but also most observers feel that there has been recent backsliding in terms of freedom of ideas and debate.

Challenges of Capital Account and Financial Liberalization

In addition to the long-run challenge of improving property rights and rule of law, China also faces short-term challenges of financial stability. Its capital account is largely closed, and it would be risky to open in the current macroeconomic environment. Credit has been growing very rapidly in China, and such excessively fast growth of credit is a good predictor of financial crises. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) calculates the “credit gap” as the difference between actual credit growth and trend. Drehmann and Tsatsaronis (2014) find that “historically, for a large cross section of countries and crisis episodes, the credit-to-GDP gap is a robust single indicator of the build-up of financial vulnerabilities.” Martinez (2016) similarly argues that domestic credit to the private sector as a percent of GDP is the most common significant indicator in forecasting banking crises. In earlier crises in Japan, Thailand, and Spain, growth of credit ran well ahead of trend for a few years. There was an investment boom that was somewhat different in each case, but with a similar end result: that a lot of poor investments were financed. Eventually these investments failed to provide sufficient return to service the loans, bad loans became manifest both in banking and in bond defaults, and a financial crisis ensued. One of the key features of these crises is that, as bad loans start to build up, banks are unsure about which clients will fail and tend to restrict lending even to potentially good clients. That drying up of credit is a key reason why the real impact of these crises is so severe. In each of the previous cases the crisis was followed by a period of deleveraging in which the stock of credit relative to GDP fell sharply.

In China’s case the BIS calculates a credit gap of about 30 percentage points of GDP—that is, the actual build-up of the stock of credit outstanding is about 30 percentage points of GDP higher than would have been predicted by trend. This is alarming, and Chinese officials have spoken of the need to reduce leverage—most recently in Governor Zhou’s warning of a “Minksy moment” for China (see Reuters 2017). Yet the growth of credit continues at a rate well in excess of the growth of nominal GDP.

While many outside analysts worry about a financial crisis in China, there are reasons to think that it will not take the predictable form. There are some special features of the Chinese financial system. First, this credit growth is domestically financed. China has a very high savings rate, around 50 percent of GDP, and does not rely on external financing in any meaningful way. In contrast, earlier credit booms in Thailand and Spain were to a large extent funded by external capital. Consequently, as their boom–bust crises unfolded, capital outflows accelerated domestic credit contraction. Japan’s case was more similar to contemporary China in that the country’s credit and investment boom was self-financed. A second, related feature of China is that the main backing for credit expansion is household deposits in banks. These tend to be very stable. This is somewhat less true in the past year as financing from nonbank institutions (shadow banking) has played a big role in credit expansion. The formal banking system primarily consists of state-owned banks lending to SOEs, including local government investment vehicles. It is hard to see a traditional banking crisis in this sector. Already many SOEs are in distress and cannot service their loans. But banks continue to lend to them and others, and it is hard to see households losing confidence in the system and pulling their deposits out. What is less clear is how the shadow banking system will operate in an incipient crisis. As some of the wealth management products backing shadow lending start to fail, it is possible households will withdraw significant amounts from these products and nonbank lending will contract. But given the state’s role in the financial sector, it seems unlikely that overall financing would contract as in a traditional financial crisis.

A second risk that is building up concerns China’s exchange rate and capital account. Until recently China had “twin surpluses” on the current and capital accounts. Large-scale reserve accumulation was required to prevent rapid appreciation of the Chinese currency. China had pegged its currency to the dollar at a rate of 8.3:1 in 1994, not an unreasonable choice for a developing economy. But by the mid-2000s productivity growth in China had resulted in the currency being increasingly undervalued. China moved off the peg in 2005, and gradually allowed some appreciation vis-à-vis the dollar. Over the past decade China’s effective exchange rate has appreciated more than any other major currency, rising by about 40 percent. The fact that the U.S. dollar had little trend between 2006 and 2013 means the RMB was rising against the dollar during that period.

China’s balance of payments situation began to change around 2014. First, the dollar began rising quite sharply against other currencies; effective appreciation was about 20 percent over a year. Initially, China followed the dollar up but began to worry that the appreciation was too much, especially if the Fed was going to normalize interest rates. Second, the capital account shifted from a surplus to a deficit. With diminishing returns to capital in China and ongoing restrictions on inward investment in many sectors, China’s capital account began to be dominated by state enterprises going out for investment and private Chinese capital moving some assets abroad. For a short period in 2014 the net capital outflows roughly matched the continuing current account surplus: China’s exchange rate was stable without any significant central bank intervention. But as 2015 began, the net capital outflows accelerated and China started selling reserves in order to prevent the currency from depreciating.

In August 2015 China carried out a “mini-devaluation” that was poorly executed and communicated. This was mostly a technical adjustment in the daily fixing system carried out under IMF advice. But it was coupled with a small, discrete devaluation that spooked global markets. It was taken as a sign that China’s economy was much weaker than previously thought and as a herald of a new exchange rate policy. Capital outflows accelerated. In a little more than a year, China’s reserve holdings went from $4 trillion to $3 trillion.

China’s officials have said publicly and privately that they have no intention to devalue the currency to spur exports and that they see no foundation for sustained depreciation of the currency. In terms of fundamentals, they are right that there is no foundation for depreciation. China has a large current account surplus, and its share of global exports hit a new historical high in 2015. Clearly, there is no competitiveness problem. Given China’s large trade surplus, any significant depreciation now would be disruptive to the world economy and could well spark trade protection from China’s partners. The problem that the country faces is that it is still fighting large capital outflows. The national savings rate has come down only a small amount from the 50 percent of GDP level, and it is likely that saving behavior will change only slowly. With diminishing investment opportunities within the country, it makes sense that significant amounts of capital are trying to leave. The reserve loss and the outflow pressure also create a reasonable fear that, whatever authorities say, they may not be able to prevent a large depreciation. That just encourages capital to try to leave sooner.

In 2016 the balance of payments stabilized to some extent. Pressures on capital outflows were eased by the clear communication from the authorities that devaluation is not the policy, the somewhat better data from the real economy, and ongoing credit stimulus of investment. Also, the government tightened up on its capital controls to make moving money more difficult.

The issue of capital controls is of crucial importance. Kaminsky, Lizondo, and Reinhart (1998) find that the ratio of broad money to international reserves is a good leading indicator of currency crises. The IMF (2015) argues that a ratio of broad money to reserves of 5:1 is a warning level for a country with bank-dominated finance, limited exchange rate flexibility, and an open capital account. Since 2010, however, there has been an alarming rise in the ratio from below 4:1 to nearly 8:1. China would be at risk of a currency crisis if it had an open capital account. Hence, it is rational that China has tightened up its capital controls over the past year. China will need to carry out significant deleveraging and financial reform before it can safely open its capital account.

Conclusion

China faces both short-run and long-run challenges to achieving the status of a major reserve currency country. In the short run, it needs to open its capital account, but it makes sense to approach this cautiously as a large overhang of debt creates a risk of financial crisis. China needs to strengthen financial institutions first through greater interest rate flexibility and a more effective resolution regime, including exit of zombie firms. It needs to introduce more exchange rate flexibility though this is hard to do when there are risks of large capital outflow and downward pressure on the currency. It is easier to introduce flexibility in the good times when market pressures will push the currency up.

In the longer run there are issues about confidence in property rights in China. Will global investors have enough confidence in China’s institutions to place large amounts of wealth there? That is the fundamental question. After an initial set of property rights reforms at the beginning of China’s reform and opening, there has been relatively little progress on that front. China now has poor economic institutions for its income level. It is a unique case of an economy that likely will be the largest in the world while still having serious institutional weaknesses. Its size alone will give the RMB a certain global status, but it is not likely to emerge as a major currency until its institutional and policy weaknesses are addressed.

References

Acemoglu, D., and Robinson, J. A. (2012) Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty. 1st ed. New York: Crown.

Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; and James, A. R. (2001) “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation.” American Economic Review 91: 1369–1401.

Dreher A., Fuchs, A.; Parks, B.; Strange, A. M.; and Tierney, M. J. (2017) “Aid, China, and Growth: Evidence from a New Global Development Finance Dataset.” AIDData (a research lab at William and Mary), Working Paper No. 46 (October).

Drehmann, M., and Tsatsaronis, K. (2014) “The Credit-to-GDP Gap and Countercyclical Capital Buffers: Questions and Answers.” BIS Quarterly Review (March). Available at www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt1403g.pdf.

Eckaus, R. S. (1997) “China.” In P. Desai (ed.) Going Global: Transition from Plan to Market in the World Economy, 415–38. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Huntington, S. P. (1968) Political Order in Changing Societies. New Haven: Yale University Press.

IMF (International Monetary Fund) (2015) “Assessing Reserve Adequacy: Specific Proposals.” Available at www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2014/121914.pdf.

Kaminsky, G.; Lizondo, S.; and Reinhart, C. M. (1998) “Leading Indicators of Currency Crises.” IMF Staff Papers 45 (1): 1–48.

Martinez, N. (2016) “Predicting Financial Crises.” Wharton Research Scholars, Paper 136. Available at http://repository.upenn.edu/wharton_research_scholars/136.

Naughton, B. (2014) “China’s Economy: Complacency, Crisis and the Challenge of Reform.” Daedalus 143 (2): 14–25.

Prasad, E. (2015) “Global Ramification of the Renminbi’s Ascendance.” In B. Eichengreen and M. Kawai (eds.) Renminbi Internationalization: Achievements, Prospects, and Challenges, 85–110. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

Ramo, J. C. (2004) “The Beijing Consensus.” London: Foreign Policy Centre (May).

Reuters (2017) “China Central Bank Warns Against ‘Minsky Moment’ Due to Excessive Optimism.” (October 19).

Williamson, J. (2012) “Is the ‘Beijing Consensus’ Now Dominant?” Asia Policy 13 (January): 1–16.

World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators. The World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) Project. Available at www.govindicators.org.

Zhao, S. (2010) “The China Model: Can it Replace the Western Model of Modernization?” Journal of Contemporary China 19 (65): 419–36.

Zhou, X. C. (2009) “Reform the International Monetary System.” Available at www.pbc.gov.cn/english/130724/2842945/index.html (March 23).

1Ramo (2004) argues that China has created a superior development model with an authoritarian system and state capitalism. Williamson (2012) and Zhao (2010) acknowledge that the model has produced rapid growth for China up to a point, but argue that the model is unsustainable.

2See Freedom House’s annual Freedom in the World reports (https://freedomhouse.org).

3The resolutions that came out of the important Third Plenum meeting in the fall of 2013 make clear that political reform is not on the agenda. See “Decision of the CCCPC on Some Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening the Reform” (www.china.org.cn/chinese/2014-01/17/content_31226494_3.htm).