The world lost a great champion of liberty with the passing of Allan Meltzer on May 8, 2017, at the age of 89. A longtime Professor of Political Economy at Carnegie Mellon University, Allan was a prodigious worker who wrote hundreds of articles and more than ten books, including his monumental A History of the Federal Reserve and more recently Why Capitalism? The latter provides a strong defense of limited government, the rule of law, private property, and free markets, which he saw as the surest means to increase the wealth of nations.

A Passion for Ideas and Policy

Allan had a passion for ideas and a desire to influence policy; he sought to make the world a better place by safeguarding economic and personal freedom. He became a major player in the marketplace for ideas—writing, teaching, advising policymakers, serving on editorial boards, cofounding the Shadow Open Market Committee and the Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy with his close colleague and lifelong friend Karl Brunner, acting as president of the Mont Pelerin Society founded by F. A. Hayek, serving on the Council of Economic Advisers, chairing the International Financial Institution Advisory Commission (also known as the “Meltzer Commission”), and participating in numerous conferences.1 He continued working right up until his death.

A Giant in Monetary Economics

I first met Allan in the early 1980s, when he began to participate in Cato’s Annual Monetary Conference. His paper “Monetary Reform in an Uncertain Environment” was delivered at the first conference, in January 1983, and published in the Cato Journal later that year; it was reprinted in The Search for Stable Money (University of Chicago Press, 1987), a book Anna J. Schwartz and I coedited.

In that article, Allan examined alternative monetary regimes and their implications for reducing risk and uncertainty. He sought a rules-based regime that would minimize uncertainty and best allow markets to flourish. He preferred, at the time, a quantity rule that would have the monetary base grow in line with the growth of real output adjusted for changes in the velocity of base money. Such a rule, he argued, would anchor expectations regarding the path of nominal income and achieve long-run price stability. However, the rule had to be credible and be supplemented with a fiscal rule that limited the taxing and spending powers of government. He did not want the Fed to finance government deficits or to allocate credit.

It is important to note that Allan was not opposed to private money. At the 1983 monetary conference, he argued:

Individuals or groups should be permitted to issue and use privately produced money or monies.… The objective of policy rules is to reduce the uncertainty that the community must bear, not to prevent voluntary risk taking [Meltzer 1983: 109].

Allan was open-minded and was willing to change his policy advice based on logic and evidence.

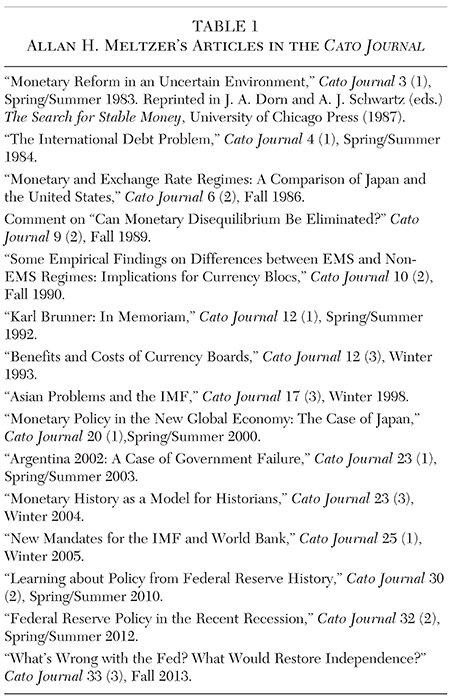

He continued to participate in Cato’s Annual Monetary Conference for many years and contributed 15 articles to the Cato Journal (Table 1). Although he was often critical of Fed policy, he thought Paul Volcker was correct in ending double-digit inflation by slowing the growth of money and credit, and that Alan Greenspan was correct in following an implicit monetary rule to prevent wide fluctuations in nominal income during the “Great Moderation.”

Meltzer, however, was highly critical of the Fed’s unconventional monetary policy and wrote in the Spring/Summer 2012 Cato Journal:

Overresponse to short-run events and neglect of longer-term consequences of its actions is one of the main errors that the Federal Reserve makes repeatedly. The current recession offers many examples of actions that some characterize as bold and innovative. I regard many of these actions as inappropriate for an allegedly independent central bank because they involve credit allocation, fill the Fed’s portfolio with an unprecedented volume of long-term assets, evade or neglect the dual mandate, distort the credit markets, and initiate other actions that are not the responsibility of a central bank [Meltzer 2012: 255].

He kept up his criticism until the end, writing articles for the Hoover Institution, where he was a Distinguished Senior Fellow,2 with such titles as “Fed Up with the Fed” (February 17, 2016), “Fed Failures” (March 9, 2016), and “Reform the Federal Reserve” (October 12, 2016), all of which appeared in Defining Ideas (Hoover’s online journal). His last article appeared on April 25, 2017, less than two weeks before he died.

The last time I saw Allan was in Zurich, in September 2016, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Karl Brunner’s birth at a conference organized by the Swiss National Bank. Allan discussed Karl’s contributions to monetary theory as well as to political economy in general. In his paper, “Karl Brunner, Scholar: An Appreciation,” he emphasized that Brunner

highlighted information, institutions and uncertainty as well as the importance of microanalysis in macroeconomics. Karl Brunner explained that nominal monetary impulses changed real variables by changing the relative price of assets to output prices. And he concluded that economic fluctuations occurred because of an unstable public sector—especially the monetary sector—that disturbs a more stable private sector, a policy lesson forgotten or never learned by many central banks.3

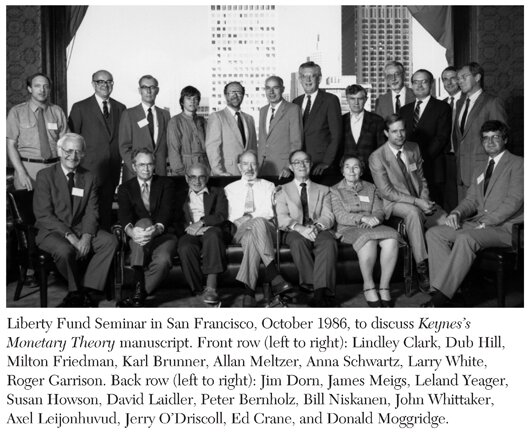

Those ideas also were central to Allan’s work—both with Karl and independently—and they are evident in his interpretation of Keynes’s monetary theory.

John Maynard Keynes and Meltzer’s Monetary Rule

In Keynes’s Monetary Theory: A Different Interpretation, Meltzer (1988) argues that the vast literature on John Maynard Keynes neglected the importance he placed on credible rules, which he thought would reduce uncertainty and improve economic welfare.

In particular, Allan was influenced by Keynes’s classic A Tract on Monetary Reform (1923), which discusses rules for domestic (internal) price stability and for international (external) price stability—that is, exchange rate stability. In thinking about a rule to reduce the variability of unanticipated changes in prices and outputs, Meltzer (1989: 78–81) draws on Keynes’s distinction and his recognition of the benefits of reducing both internal and external instability. The problem, of course, is to choose the appropriate institutional framework. Countries operating independently cannot achieve both internal and external stability, argued Keynes, unless a key country anchors its price level by enforcing a credible rule.

Building upon Keynes’s insights, Meltzer (1989: 78) notes that if each major trading partner makes domestic price stability a priority, then uncertainty about the future path of prices will diminish and exchange rates among the partners will be more stable. To realize both internal and external stability, Meltzer proposes a simple rule: each major country should set “the rate of growth of the monetary base equal to the difference between the moving average of past real output growth and past growth in base velocity” (ibid., p. 83). If each country complies, the rule will reduce the “variability of exchange rates arising from differences in expected rates of inflation.”4

Meltzer’s proposed rule is “forecast free” and adaptable; it is mildly activist but nondiscretionary, similar to Bennett McCallum’s (1984) monetary rule. By choosing to stabilize the anticipated price level rather than the actual price level, monetary authorities will not need “to reverse all changes in the price level,” argues Meltzer (1989: 79). Instead, the actual price level is allowed “to adjust as part of the process by which the economy adjusts real values to unanticipated supply shocks.” In particular, Meltzer’s monetary rule “does not adjust to short-term, transitory changes in level, but it adjusts fully to permanent changes in growth rates of output and intermediation (or other changes in the growth rate of velocity) within the term chosen for the moving averages” (ibid., p. 81).

Under the Fed’s current operating procedure, in which the Fed sets a federal funds rate target range with the rate of interest on excess reserves (IOER) as its upper limit and the Fed’s overnight reverse repurchase (ON RRP) agreement rate as its lower limit, Meltzer’s monetary rule could no longer work as he imagined it might.5 Because the IOER rate is higher than comparable market rates, at least some banks now find it worthwhile to accumulate excess reserves instead of trading them for other assets. The economy is, in other words, kept in a purpose-made “liquidity trap,” so that the traditional monetary “transmission mechanism” linking increases in the monetary base to changes in bank lending, overall spending, and inflation, no longer functions as it once did. Instead, barring vast changes in the quantity of base money (“quantitative easing”), to alter its policy stance the Fed has to change its IOER and ON RRP rates, thereby influencing not the supply of but the overall demand for the Fed’s deposit balances.

Before serious consideration can be given to implementing any rules-based monetary regime, the Fed needs to normalize monetary policy by ending interest on excess reserves and shrinking its balance sheet to restore a precrisis fed funds market. Once changes in base money can be effectively transmitted to changes in the money supply and nominal income, Meltzer’s rule would reduce uncertainty and spur investment and growth.

The key point, however, is that Allan wanted to explore alternative monetary rules and select those he thought would work best to reduce the variability of prices and output. That comparative-institutions approach was evident in all his work. He recognized that, ultimately, the choice of a rule would be heavily influenced by the political economy. His careful scholarship was intended to help shape the climate of ideas and public policy in the direction of what Richard Epstein (1995) has called “simple rules for a complex world.”

A Breadth of Knowledge

Although Allan was known primarily for his work on monetary theory and history, he was deeply interested in the role of government in a free society; the relation between institutions, incentives, and behavior; the determinants of economic growth; the theory of public choice; the damaging effects of official foreign aid; and the distribution of income.6 He wrote many articles for the popular press, including the Wall Street Journal, Los Angeles Times, and Financial Times, and he was always willing to help younger scholars and students understand the complexities of political economy.

A Man of Integrity

Allan Meltzer was a great scholar and teacher, a friend of liberty, a man of integrity who kept his word,7 and a fine human being. He was persistent in his research and his life. Allan taught at Carnegie Mellon for 60 years and was married to his lovely wife Marilyn for 67 years.

When Allan was five years old, he lost his mother and went to live with his grandmother for several years until he moved to Los Angeles where his family ran a business. Reflecting on his early years with his grandmother, Allan said, “Her most important influence on my career and my outlook was her strongly held belief that, in America (and only in America), there were no real limits other than ability to what one could achieve by personal effort” (Meltzer 1990: 22).

In his many accomplishments and honors, Allan certainly realized the American Dream, and had a life well lived.8 He will be sorely missed, but his work will live on.

References

Brunner, K. (1987) “Policy Coordination and the Dollar.” Shadow Open Market Committee: Policy Statement and Position Papers (PPS 87-01): 49–51. Center for Research in Government Policy & Business, University of Rochester (March).

Dorn, J. A. (2017) “Allan H. Meltzer: A Life Well Lived (1928–2017).” Alt-M (May 12).

Epstein, R. A. (1995) Simple Rules for a Complex World. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Ihrig, J.; Meade, E.; and Weinbach, G. (2016) “The Federal Reserve’s New Approach to Raising Interest Rates.” FEDS Notes (February 12). Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Available at www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/notes/feds-notes/2016/the-federal-reserves-new-approach-to-raising-interest-rates-20160212.html.

Keynes, J. M. (1923) A Tract on Monetary Reform. London: Macmillan.

McCallum, B. T. (1984) “Monetary Rules in the Light of Recent Experience.” American Economic Review 74 (May): 388–96.

Meltzer, A. H. (1983) “Monetary Reform in an Uncertain Environment.” Cato Journal 3 (1): 93–112.

__________ (1988) Keynes’s Monetary Theory: A Different Interpretation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

__________ (1989) “On Monetary Stability and Monetary Reform.” In J. A. Dorn and W. A. Niskanen (eds.) Dollars, Deficits, and Trade, 63–85. Boston: Kluwer. This paper was originally presented at the Third International Conference of the Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies at the Bank of Japan, June 3, 1987.

__________ (1990) “My Life Philosophy.” American Economist 34 (1): 22–32.

__________ (2012) “Federal Reserve Policy in the Great Recession.” Cato Journal 32 (2): 255–63.

__________ (2016) “Karl Brunner, Scholar: An Appreciation.” Paper presented at the Swiss National Bank Conference “Karl Brunner Centenary,” Zurich (September 9). Available as Hoover Institution Economics Working Paper No. 15116, Stanford University (October 2015).

Selgin, G. (2017) “Monetary Policy v. Fiscal Policy: Risks to Price Stability and the Economy.” Testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Financial Services (July 21). Available at www.cato.org/publications/testimony/monetary-policy-v-fiscal-policy-risks-price-stability-economy.

__________ (2018) “FLOORED! How a Misguided Fed Experiment Deepened and Prolonged the Great Recession and Why the Fed—or Congress—Ought to End It.” Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives (February 7). Washington: Cato Institute.

Taylor, J. B. (2017) “Making the Rules and Breaking the Mould (Allan Meltzer: 1928–2017).” Central Banking (June 19). Available at www.centralbanking.com/central-banks/economics/3260601/making-the-rules-and-breaking-the-mould-allan-meltzer-1928-2017.

1 For an excellent summary of Meltzer’s contributions to public policy, see Taylor (2017).

2 Before Meltzer moved to the Hoover Institution, he was a Visiting Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., for many years.

3 See Meltzer’s “Abstract” in his Hoover Institution Economics Working Paper No. 15116 (October 2015).

4 Meltzer’s proposal is similar to Brunner’s call for a “club of financial stability” (Brunner 1987: 50).

5 For an analysis of the Fed’s postcrisis operating system, see Ihrig, Meade, and Weinbach (2016); Selgin (2017, 2018).

6 Meltzer viewed economics as “a policy science, not a branch of applied mathematics.” He argued that “economics will be poorer if it does not include institutions and the incentives embodied in the rules, institutions or arrangements that we call society” (Meltzer 1990: 27).

7 In the foreword to volume 1 of Meltzer’s A History of the Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan wrote, “Allan Meltzer has spent a lifetime inquiring into monetary economics, and he calls the evidence as he sees it” (Greenspan 2003: x).

8 Meltzer’s many honors include: Distinguished Fellow, American Economic Association; Irving Kristol Award, American Enterprise Institute; Distinguished Professional Achievement Medal, UCLA; The Adam Smith Award, National Association for Business Economics; The Bradley Foundation Award; The Harry Truman Award for Public Policy; and the Distinguished Teacher Award, International Mensa Foundation.