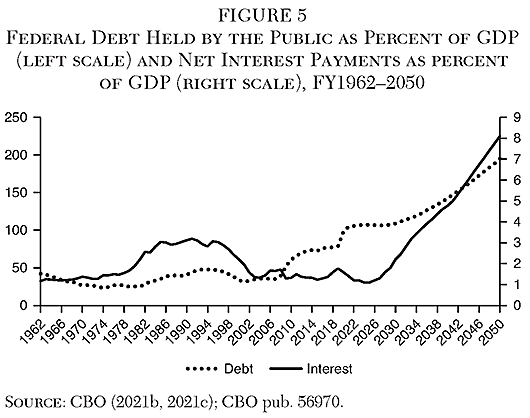

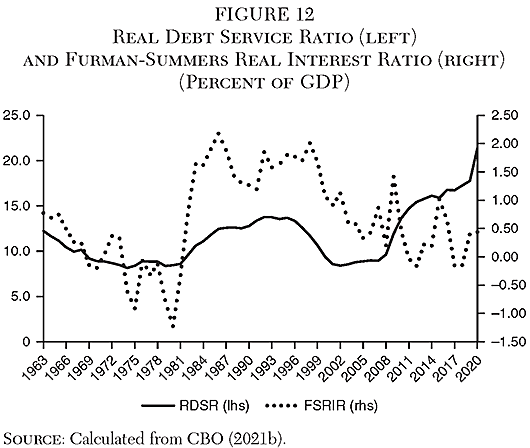

… there is now widespread agreement among economists that debt is far less of a problem than conventional wisdom asserted. Among other things, while the level of federal debt may seem high, low interest rates mean that the burden of servicing that debt is actually very low by historical standards.

The political sphere has been quick to seize on the new view. As Thomas Friedman (2021) wrote in the New York Times, “a powerful consensus … has taken hold on both parties”—“we are in a new era of permanently low interest rates, so deficits don’t matter .…”

Among economists, the new nonchalance about debt is by no means unanimous. The Congressional Budget Office (2021c: 5) emphasizes the risks associated with debt on track to exceed 200 percent of GDP by 2051:

Debt that is high and rising as a percentage of GDP boosts federal and private borrowing costs, slows the growth of economic output, and increases interest payments abroad. A growing debt burden could increase the risk of a fiscal crisis and higher inflation as well as undermine confidence in the U.S. dollar.

Likewise, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (2021) has consistently been among the most vocal critics of the outlook for rising public debt. Moreover, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen stated in 2017 that the United States was on an “unsustainable debt path,” and in confirmation hearings, she reiterated that “there are long-term budget challenges” (Yellen 2021: 26).

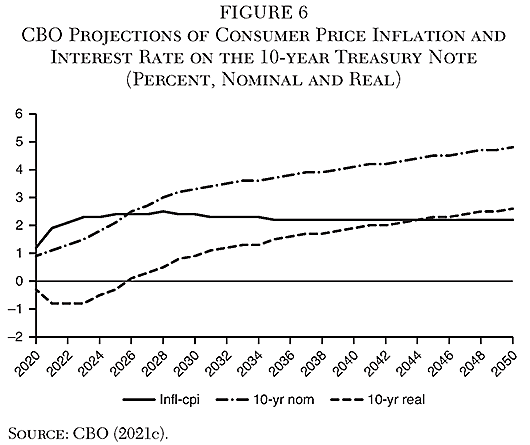

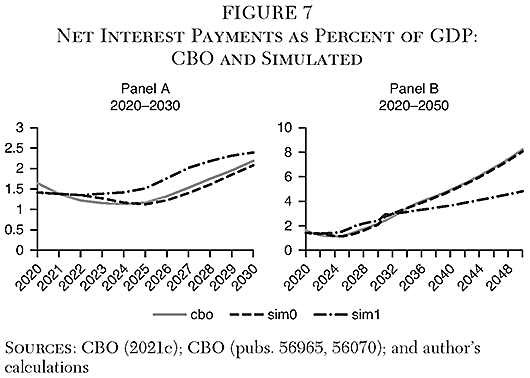

In contrast, Furman and Summers (2020: 28, 31) argue that “CBO‘s forecasts of net interest as a share of GDP have been systematically biased toward being too high” and that “policymakers should put relatively little weight on projections for ten years or more in the future.”

A core problem with ignoring debt because of low interest rates is rollover risk. Upon maturity, a federal note or bond must be refinanced with new borrowing. As the debt to GDP ratio climbs, at some point financial markets are likely to demand higher interest rates—as seen in the “taper tantrum” of 2013 when rates reacted sharply to the announcement that the Federal Reserve would wind down “quantitative easing” purchases of federal debt. Even though in principle the United States could always inflate away its real debt because it borrows in its own currency, the prospect of a need to do so would widen the inflation risk premium. Moreover, because of likely political intolerance to inflation high enough to make a sharp reduction in outstanding real debt, financial markets could begin to incorporate a credit-default risk premium.

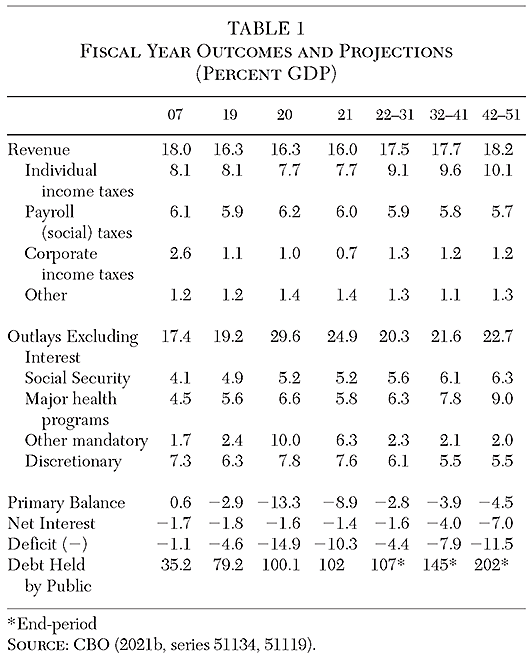

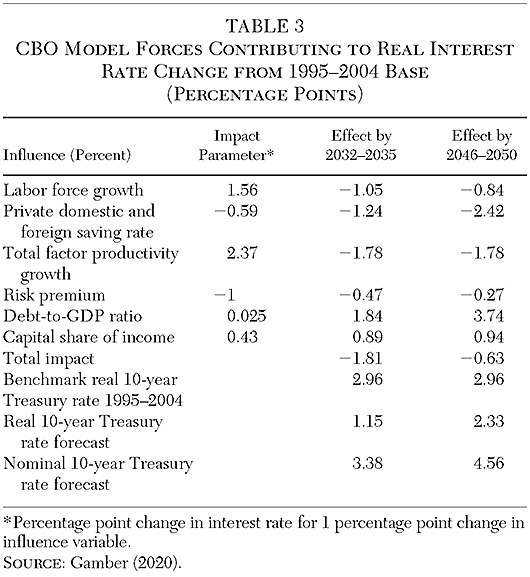

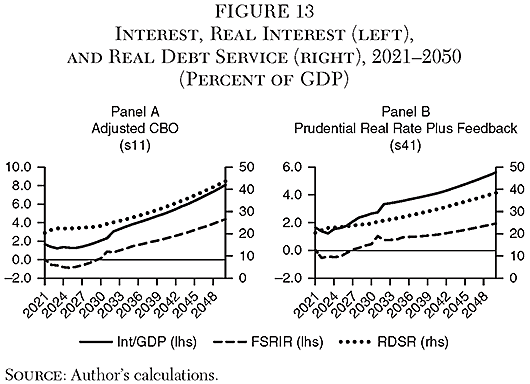

The causes of the near-zero real 10-year Treasury rate in recent years remain the subject of debate. The hypotheses include rising inequality (combined with a higher marginal saving rate of the rich), the rise in China’s contribution to the global pool of savings, heightened risk aversion in the wake of the Great Recession (and now the pandemic) and a corresponding rise in demand for safe assets, a long-term decline in growth, a shift to new technologies requiring less capital, and others (Mankiw 2020). As discussed below, the Congressional Budget Office has attempted to model the various influences causing the low rates, and finds that, even taking such trends into account, the path of rising debt relative to GDP brings the real 10-year rate back up to 1.4 percent by 2031, an average of 1.6 percent in 2032–2041 and 2.3 percent in 2042–2051, and 2.7 percent by 2051 (CBO 2021b; 2021c: 34, 43).

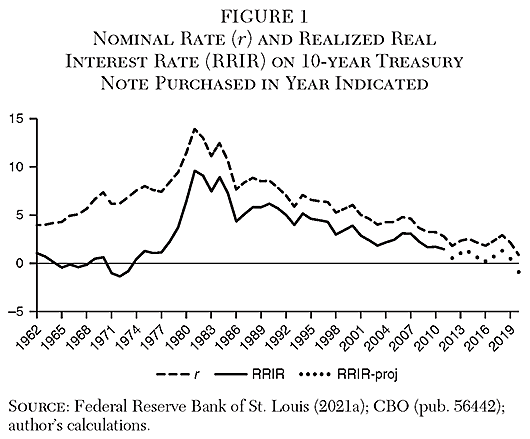

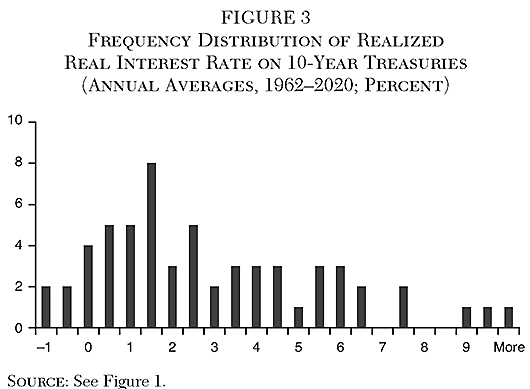

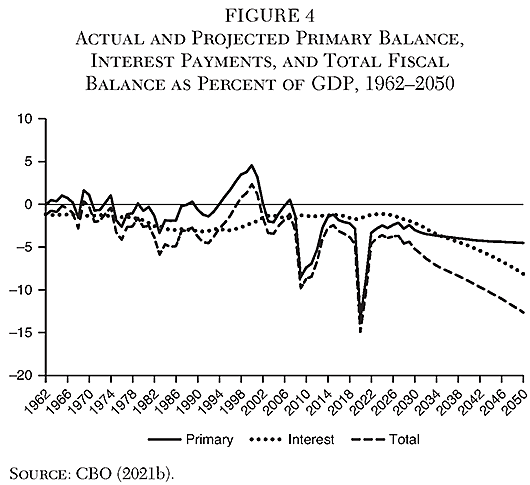

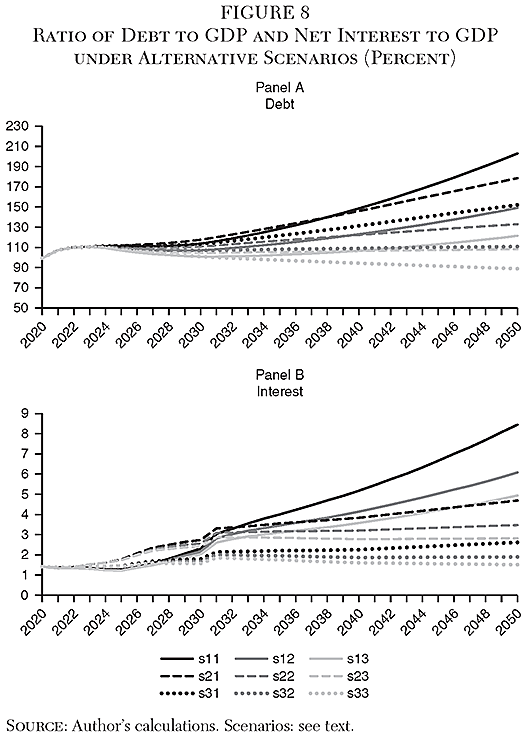

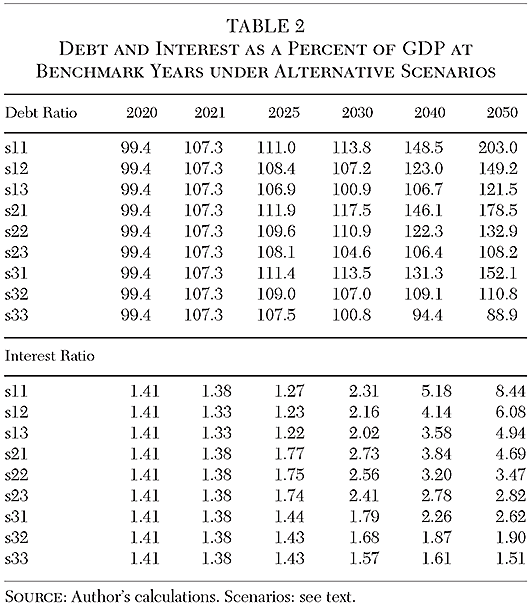

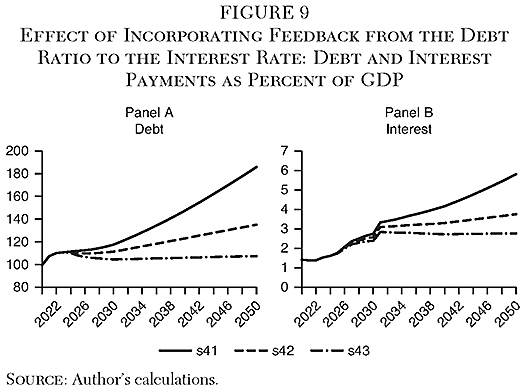

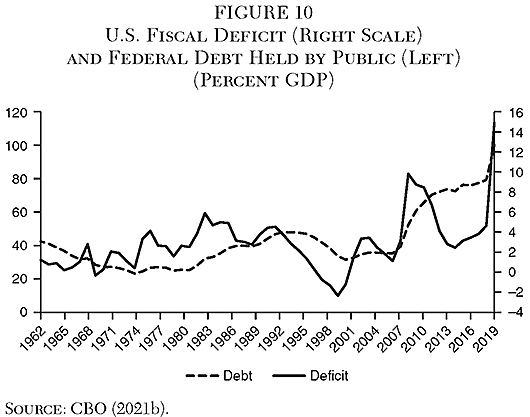

This article takes the approach of setting a “prudential” floor for the real interest rate in projecting federal debt. It first calculates the ex post realized real interest rate (RRIR) on the 10-year Treasury note over the past six decades. It then sets the prudential floor for the RRIR at 1 percent, the 33rd percentile in the past distribution of real rates. Using a simple accounting model that estimates the interest obligation on each future vintage of new borrowing, I find that a real rate of 1 percent by 2025 causes a path of interest burden that is close to the historical average of 1.9 percent of GDP by that time, and that reaches 4.7 percent of GDP by 2050.2 Incorporation of the impact of rising debt on the real interest rate raises the projection further to 5.8 percent of GDP by 2050. A sizable persistent primary deficit of about 3 percent of GDP, rising to over 4 percent, thus yields a dangerously high long-term debt burden whether measured by the ratio of interest or debt to GDP.

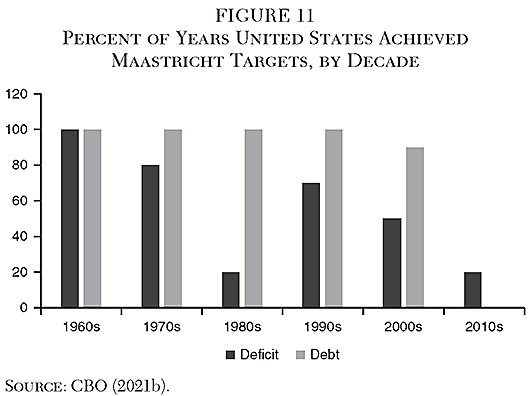

At a real interest rate of 1 percent, classic Maastricht fiscal targets would shift from 60 percent of GDP for the debt to GDP ratio to about 130 percent, and from 3 percent of GDP to 4 percent for the fiscal deficit. However, even these more lenient targets would not be met unless primary deficits are cut to about 1 to 2 percent of GDP, well below their current path rising from about 3 percent of GDP to 4.5 percent by the 2040s as social security and especially health outlays escalate.

The broad finding of this study is that the U.S. debt burden is on a long-term path to unprecedented heights even when measured by interest payments, despite the low interest rates of recent years. This diagnosis remains valid for an alternative metric of real debt service (interest plus amortization) relative to real GDP. Curbing primary deficits will be necessary to moderate this precarious path.

Real Interest Rate versus Growth and Debt Sustainability

Low real interest rates in recent years have focused attention on the analysis of public debt sustainability in the “r − g” framework: the race between debt build-up from interest paid on outstanding debt and growth in the GDP base available to service the debt. In 2003 I set forth such a framework in analyzing debt sustainability for Argentina after its default in 2001 (Cline 2003, Annex A). The primary (noninterest) fiscal surplus needed to keep the debt to GDP ratio from rising, as a fraction of GDP, turned out to be the real interest rate minus the real growth rate, multiplied by the initial ratio of debt to GDP, and all divided by unity plus the real growth rate plus inflation.3 With low real interest rates equal to or less than the growth rate, the principal policy inference has been that public debt is not much of a problem.4 Cline (2021, Appendix A) sets forth the basic equations of the “r − g” debt dynamics.

A major practical problem with such an inference is that, when there are large structural primary deficits, a zero contribution to a rising debt ratio from the standpoint of interest on inherited debt does not suffice to prevent brisk escalation in the debt ratio. A central implication of this fact is that policy initiatives that have the effect of locking in new ongoing primary deficits can cause debt problems even when the interest rate is at or below the growth rate. The discussion of structural primary spending trends below considers the magnitude of the primary deficit problem.

The Long-Term Trend toward Lower Real Interest Rates

Despite the low interest rates in recent years, it would be imprudent to ignore actual levels of real interest rates in recent decades in designing fiscal policy. The best measure of federal borrowing costs is the rate on the 10-year note. Average residual maturity on federal debt has been about 6 years since 2013, about the length that would be expected if all debt were issued with 10-year maturities.5

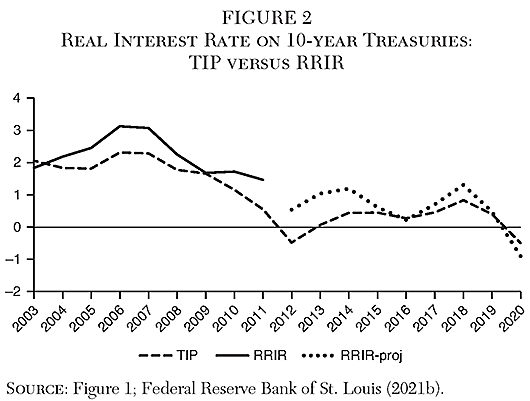

Measuring the real interest rate is not straightforward. Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) were not introduced until the late 1990s, and data series on 10-year TIPS only begin in 2003. Moreover, TIPS account for only about 9 percent of outstanding debt (CBO, pub. 56165: 6). However, a correct measure of the real interest rate eventually realized on a nominal 10-year note cannot be calculated simply by deducting the inflation rate from the 10-year interest rate for the year of issuance. The reason is that the real interest burden depends on the subsequent time path of inflation in comparison to the steady year-of-issuance nominal interest payments.

I calculate the 10-year RRIR as the internal rate of return on an investment purchased in year 0, paying annually over each of the subsequent 10 years the average coupon rate of 10-year government obligations issued year 0, and returning principal in the 10th year. The stream of return is deflated by the PCE (personal consumption expenditure) price index.6

Figure 1 shows the resulting estimates of RRIR on the 10-year Treasury note, from 1962 through 2011 actual (solid line) and then expected for 2012–2020 (dotted line). (The actual realized rate for the Treasury note purchased in 2015, for example, will not be known until 2025). The expected path for 2012–2020 applies PCE inflation as projected in CBO (pub. 56442).7