One of the main topics highlighted in the field of economic policy applications is the impact of taxation on labor. In an era in which macroeconomic stability, technological change, and globalization pressure the job market, there exists no strong consensus in the literature on how exactly taxation influences growth, choice between work and leisure, share of income attributed to labor, or participation in different job market segments. This article focuses on employment levels and uses the results of the World Economic Forum (WEF) Executive Opinion Survey (EOS) between 2013 and 2017 to bypass several challenges often faced in the literature. By doing so, we complement the insights of the existing literature by establishing that, in institutionally mature countries, taxation that is deemed by a survey of business executives to pose a disincentive to work reduces employment.

Impact of Taxes on Employment and the Labor Income Share

The impact of taxes on employment and labor’s share of income has received attention in seminal work like Ramsey (1927), Mirrlees (1971), Hall (1973), Rosen (1979), Hausman (1980, 1981), Stern (1986), Hausman and Poterba (1987), Triest (1990), Feldstein (1995), and Diamond (1998). Over the years, the literature matured trying to overcome limitations posed by data availability and methodological challenges. Meghir and Phillips (2010), as well as Mankiw, Weinzierl, and Yagan (2009), summarized the key insights of the existing literature reflecting the simple reality that both income and substitution effects are at work.1 Manski (2012a, 2012b) is not alone in arguing that there is no certain answer to the question of what impact a tax increase has on labor.

In spite of the controversies found in the literature, there exists sufficient empirical evidence to suggest that increasing taxes on labor leads to a slowdown in economic growth and a decline in employment, as well as an encouragement of undeclared work (Davis and Henrekson 2004; Frederiksen, Graversen, and Smith 2005). This appears to be true at least for high-tax European and OECD countries (Planas, Roeger, and Rossi 2003; Bassanini and Duval 2006) and for more vulnerable population groups (Blundell 2012; Neumark and Shirley 2020).

The aforementioned studies often use household survey data, which are available for net earnings, and thus are able to focus directly on the impact of changes in net income on labor supply and equilibrium outcomes. These approaches mostly focus on within-group variation or on specific parts of the distribution of employees and incomes, and especially on kinks or policy-induced changes in parts of the tax wedge schedule. Thus, they can avoid identification problems, but other problems, such as the endogeneity of the earners’ distribution across income brackets, may persist.2

In recent decades, some researchers have argued that the stability of labor’s share of income has been declining due to technological change and, to a lesser extent, certain aspects of globalization (IMF 2017: chap. 3; Dao, Das, and Koczan 2019). Those trends are found to harm lower- and middle-skilled workers and jobs that are easy to routinize, but no definite consensus has been formed. Finally, some differentiation appears in this literature according to country groups, time, and the specifications of each analysis that includes a wide array of independent variables ranging from market regulation to education.

A number of the researchers who have investigated the labor income share have also tried to add the impact of taxation. Estrada and Valdeolivas (2012) examined the impact of taxes on labor income and did not find a statistically significant relationship. They argued that a nonwage component is included in the total compensation of employees, implying that an identification problem exists even before one can be concerned about endogeneity (Li and Lin 2016). Stockhammer (2013) included the tax wedge but failed to find a significant impact on the labor income share. In other research, the European Commission (2007: chap. 5) analyzed the impact of the tax wedge on specific subgroups and found an impact on lower- and upper-tier income employment groups.

A methodological issue that emerges when the labor income share is used is the need to account for the income attributed to self-employed labor but lumped with capital income by national accounts. This problem is commonly corrected by an assumption that the self-employed earn the same income as wage earners (Arpaia, Pérez, and Pichelmann 2009; European Commission 2007). In addition, according to researchers like Cho, Hwang, and Schreyer (2017), as capital becomes more important so does depreciation. Hence, labor income will inevitably decline relative to gross income, if this fact is not properly accounted for. We are not aware of research with such an adjustment that examines the impact of taxation.

In view of the above, we perceive an opportunity to use a survey from the World Economic Forum to study the relationship between taxation and employment levels at a macroeconomic level.

Insights from the World Economic Forum Survey

For the last several decades, the World Economic Forum has conducted an annual EOS among businesses in most countries, both developed and developing. For this survey, a questionnaire is distributed by local partners to a sample of local businesses that have to meet certain criteria to ensure representativeness by size and sectors. Furthermore, a minimum number of completed or largely completed surveys have to be received in order to ensure the inclusion of a country in the annual publication, with the WEF providing extensive details about the scope and technical execution of the survey (see, e.g., World Economic Forum 2014).

The questionnaires tend to be completed by high-ranking executives of companies that have a structure to deal with such questionnaires and, as a result, tend to be larger and part of the official economy. Therefore, it has to be noted that the answers provided may represent a different share of economic activity in each country according to its institutional maturity and the prevalence of the unofficial economy and thus estimated elasticities may be affected—for example, work on tax morale (Kaplow 2007; OECD 2019).

In this article, we are particularly interested in the EOS question asking executives “to what extent do taxes reduce the incentive to work?” In a ranking of 1 to 7, 1 = “significantly reduce the incentive to work,” while 7 = “do not reduce incentive to work at all.” Questions regarding the impact of taxation were included in the survey from 2013 until 2017.

This dataset allows us to avoid the endogeneity problem when the average tax wedge is used as an independent variable. In addition, the EOS covers almost all countries, which allows us to expand beyond the dataset for developed countries. Using the EOS response as a proxy for taxation, however, comes with a number of shortcomings: particularly, the inability to estimate elasticities using hard data. Nevertheless, we are encouraged by the fact that a previous use of EOS data by Feldmann (2003) led to results that were verified with the use of hard data, once the datasets were developed by the OECD (2004).

Even though we can pair a dependent variable that is not affected by the tax wedge with measures of taxation and that can be used in a macroeconomic analysis, we are still missing data and a theoretical justification that would allow us to remove the tax wedge from the labor share of income even after correcting for depreciation and self-employment. Therefore, we will use as a dependent variable the World Bank employment to population ratio (i.e., the percentage of working age population employed), even though this means we will investigate only the number of jobs and ignore qualitative aspects of these jobs. In the end, in spite of the limitations still present, the closer examination of the WEF EOS dataset promises to provide some useful insights.

The aggregate WEF Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) shows that for the upper tier of developed countries, which includes members of the European Union (EU) and OECD, a clear negative relationship exists between the ranking of taxation as a disincentive to work and the employment rate of the population as reflected by the five-year averages of the available panel data for these countries. At the same time, it is interesting to point out that for countries that rank lower, including also some EU members, the relationship is gradually weakened.

The deterioration of the results as countries ranked at lower competitiveness and institutional maturity are included in the sample is interesting but not novel (Stockhammer 2017). Furthermore, Bassanini and Duval (2006, 2009) found a strong intuitive relationship between unemployment and the OECD tax wedge by focusing on averages in 20 OECD countries. Even though the separation of a dataset in subgroups may be considered arbitrary, we proceed as such a separation allows a comparison of findings among the group of highly competitive countries with groups of less competitive countries. In addition, we observe no highly competitive countries in which an unfavorable ranking by the WEF EOS on the issue of taxation is paired with a relatively high employment ratio.3

Analysis of the Dataset

Following a number of separate regressions, we split the sample of 101 countries for which both WEF and World Bank data were available into three groups:4 (1) 41 lower-ranking countries using the WEF GCI, generating 205 data points; (2) 41 middle-ranking countries with 205 data points for all five years covered by our data; and (3) the top-ranked 19 countries.5 The top group was selected with a threshold that marked a trend to reduce the robustness of the results once lower-ranking countries were included and Luxemburg and Malaysia were removed, as their attributes appeared to show performance not explained well by the independent variables.

Our independent variables are all selected from the WEF GCI subindexes. Numerous subindexes were tried in a way that gave precedence to variables that represent answers to EOS questions and that touch topics that are related with variables identified as relevant in the literature. Broader indexes of the WEF GCI that bundle a number of selected per case subindexes, and incorporate statistical data with results of the EOS, were also tried. In the end, some of the broadest so-called pillars of the WEF GCI were selected as they offered a consistent approach and the results obtained remained intuitively compatible. However, in order to ensure desired properties—such as exogeneity of the independent variables, reduced vector inflation factors, and increased relevance in certain country groups—some subindexes were selected. Thus, the pillar “goods market efficiency” was removed, the pillar on infrastructure was replaced by “quality of infrastructure,” and the subindexes on “foreign competition” and “domestic market size” were included as representative of the pressures of globalization and the ability to cater to a large nontradables sector. Also, the pillar on “labor market efficiency” was replaced by either “hiring and firing practices” or “flexibility of wages,” because that pillar includes the tax wedge. Finally, measures of access to finance were not used given their correlation with the pillar for the macroeconomic environment.

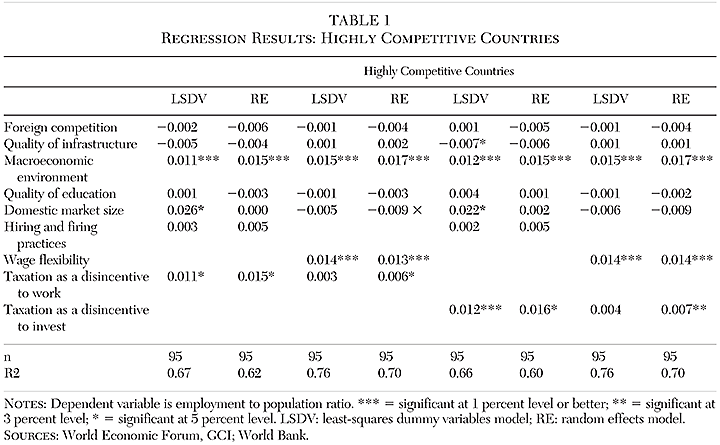

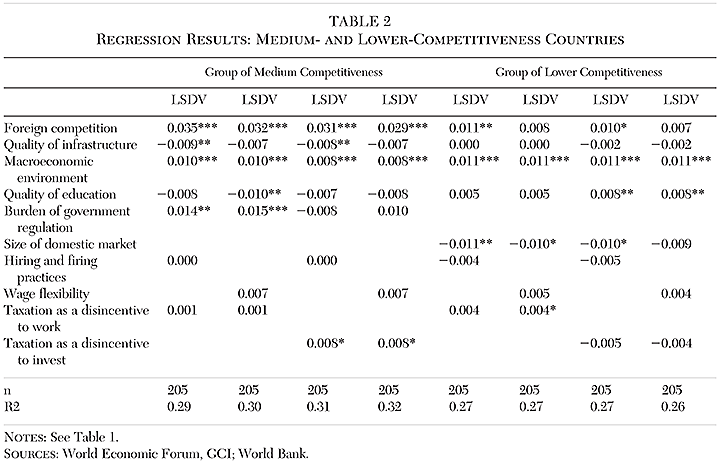

Regarding the endogeneity of the independent variable, the view of executives regarding “taxation as a disincentive” to work and invest, a two-stage least squares regression was performed adding the EOS answers on “government efficiency” and the “the existence of irregular payments” that were statistically significant in many iterations. For the group of middle-ranked countries, “domestic market size” was replaced by “burden of government regulation.” The latter, especially in the group of highly competitive countries, demonstrated high multicollinearity and endogeneity, reminding us of arguments that the relationship between taxation and regulation can be an influencing factor (Schoefer 2010). The variables finally included, and the results obtained by the relevant least squares dummy variable (LSDV) and random effects approaches are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

One can see the overarching importance of the macroeconomic environment in all country groups and for all examined types of variation.6 We also note that foreign competition tends to enter with a negative sign in highly competitive countries, albeit without significance in the specifications used here. It also has a relatively large, positive, and significant sign for the group of countries with medium competitiveness until their domestic market size is added. The controversy about both the positive and negative effects of globalization in developed and developing countries seem to be present here as well.

It is also interesting that the burden of government regulation, which along with other variables like goods market efficiency was not significant and usually endogenous for the group of highly competitive countries, turns out to be important (i.e., positive, with a relatively high value) in iterations that examine the impact of taxation on labor in countries of medium competitiveness, possibly as it is not a given in this group. Moreover, the existence of a large domestic market seems to be a burden for employment for less competitive countries. This surprising finding merits further investigation and may be related to the positive effect of foreign competition, suggesting that large domestic markets isolated from international markets may struggle to create jobs in less competitive countries. Regarding education, our quantitative measure of labor market performance appears not to be affected. This result appears in line with the literature and arguments that education is not a necessary condition to increase jobs (Hausmann 2015), but more likely a condition to improve job and life quality. The results regarding the quality of infrastructure may hint either toward the inefficient use of government or toward capital-labor substitution.

Regarding taxation, the main focus of our analysis, we find that, for highly competitive countries, taxation as a disincentive to work is important. It has the expected sign, in both LSDV and random effects models—provided the measure of labor market regulation does not include the flexibility of wages. Once that variable is included, only the random effects model assigns significance to taxation as a disincentive to work, albeit with a coefficient that is much reduced.7

When looking at taxation as a disincentive to investment, the results are similar. In the group of countries with medium competitiveness, the appropriate LSDV effects model assigns significance only to the taxation as a disincentive to invest, while the taxation as a disincentive to work reappears with some significance in the group of countries with lower competitiveness. In the case of the latter groups of countries, the between-country variation model, not reported here, does not reveal any significance of taxation.

It is also noteworthy that, while Bassanini and Duval (2006, 2009) included country LSDV effects, which remove between-country variation, and used the tax wedge on the average wage earned by a single earner couple with two children, which may suffer from endogeneity issues, their focus on employment rates of OECD member countries removes the most serious identification concerns. In the end, they established a significant impact of taxation on work both with their random effects and LSDV effects models.

Our findings show that highly competitive countries can reduce taxation on work and investment to influence employment. In addition, ensuring wage flexibility can lead to the retention of jobs, albeit at presumably lower wages should policymakers decide for increased taxation. However, countries of medium competitiveness may find it challenging to recoup employment losses induced by increased taxes on investment, especially if globalization is retrenching.

Conclusion

Among developed countries that rank high in competitiveness and institutional maturity and that share common key attributes, it is argued that, when taxation is considered by business executives to be a disincentive to work and invest, lower levels of employment for a given population are observed. This result is based on responses to the WEF’s EOS, which offers us the opportunity to bypass a number of challenges that have restrained other researchers from examining both within- and between-variation among countries in the case of labor income taxation.

The dataset used also allows for an extension of the analysis to less competitive and developing countries that often are not part of existing research. Reaffirming the finding of research that does manage to extend its analysis beyond highly developed countries, we find that some results change materially among the three different groups of highly competitive, middle-ranked, and less-competitive countries. Exposure to globalization exerts significant and positive forces on employment, especially on countries in the middle of the distribution. Moreover, in this group, only taxation deemed as a disincentive to invest, and not as a disincentive to work, affects employment.

We live in a world with multiple challenges to the growth globalization has supported for decades and that faces the inevitable costs a shift to sustainable growth will impose on parts of the world and workforce. In addition, the ability of developing countries to compete on the basis of attractive taxation of investment may soon be limited. As a result, a better understanding of the way various types of taxation impact employment in different country groups may help policymakers better navigate these challenging times.

References

Arpaia, A.; Pérez, E.; and Pichelmann, K. (2009) “Understanding Labour Income Share Dynamics in Europe.” Economic Papers 379, European Commission.

Bassanini, A., and Duval, R. (2006) “Employment Patterns in OECD Countries: Reassessing the Role of Policies and Institutions.” OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper No. 35 and OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 486.

__________ (2009) “Unemployment, Institutions, and Reform Complementarities: Reassessing the Aggregate Evidence for OECD Countries.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 25 (1): 40–59.

Blundell, R. (2012) “Tax Policy Reform: The Role of Empirical Evidence.” Journal of the European Economic Association 10 (1): 43–77.

Chetty, R. (2012) “Bounds on Elasticities with Optimization Frictions: A Synthesis of Micro and Macro Evidence on Labor Supply.” Econometrica 80 (3): 969‑1018.

Cho, T.; Hwang, S.; and Schreyer, P. (2017) “Has the Labour Share Declined? It Depends.” OECD Statistics Working Paper No. 2017/01.

Dao, M. C.; Das, M.; and Koczan, Z. (2019) “Why Is Labour Receiving a Smaller Share of Global Income?” Economic Policy 34 (100): 723–75.

Davis, S., and Henrekson, M. (2004) “Tax Effects on Work Activity, Industry Mix and Shadow Economy Size: Evidence from Rich-Country Comparisons.” NBER Working Paper No. 10509.

Diamond, P. (1998) “Optimal Income Taxation: An Example with a U‑Shaped Pattern of Optimal Marginal Tax Rates.” American Economic Review 88 (1): 83–95.

Estrada, Á., and Valdeolivas, E. (2012) “The Fall of the Labour Income Share in Advanced Economies.” Banco de Espania, Documentos Ocasionales, No. 1209.

European Commission (2007) “The Labour Income Share in the European Union.” In Employment in Europe 2007, Chap. 5. Brussels: Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities.

Feldmann, H. (2003) “Labor Market Regulation and Labor Market Performance: Evidence Based on Surveys among Senior Business Executives.” Kyklos 56 (4): 509–40.

Feldstein, M. (1995) “The Effect of Marginal Tax Rates on Taxable Income: A Panel Study of the 1986 Tax Reform Act.” Journal of Political Economy 103 (3): 551–72.

Frederiksen, A.; Graversen, E. K.; and Smith, N. (2005). “Tax Evasion and Work in the Underground Sector.” Labour Economics 12 (5): 613–28.

Hall, R. E. (1973) ‘Wages, Income and Hours of Work in the U.S. Labor Force.” In G. G. Cain and H. W. Watts (eds.), Income Maintenance and Labor Supply. Cambridge, Mass: Academic Press.

Hausman, J. (1980) “The Effect of Wages, Taxes and Fixed Costs on Women’s Labor Force Participation.” Journal of Public Economics 14: 161–94.

__________ (1981) “Labor Supply.” In H. J. Aaron and J. A. Pechman (eds.), How Taxes Affect Economic Behavior, 27–83., Washington: The Brookings Institution.

Hausmann, R. (2015) “The Education Myth.” Project Syndicate (May 31).

Hausman, J., and Poterba, J. (1987) “Household Behavior and the Tax Reform Act of 1986.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 1 (1): 101–19.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2017) “Understanding the Downward Trend in Labor Income Shares.” In World Economic Outlook: Gaining Momentum? 121–70. Washington: IMF (April).

Kaplow, L. (2007) “Taxation.” In A. M. Polinksy and S. Shavell, (eds.), Handbook of Law and Economics, Vol. 1, Chap. 10. New York: Elsevier, North-Holland.

Li, C. G., and Lin, S. G. (2016) “Tax Progressivity and Tax Incidence of the Rich and the Poor.” Economics Letters 134: 148–51.

Mankiw, G.; Weinzierl, M.; and Yagan, D. (2009) “Optimal Taxation in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 23 (4): 147–74.

Manski, C. (2012a) “Identification of Income-Leisure Preferences and Evaluation of Income Tax Policy.” Cemmap Working Paper No. 07/12, Institute for Fiscal Studies.

__________ (2012b) “Income Tax and Labor Supply: Let Us Acknowledge What We Do Not Know.” Voxeu (August 23).

Meghir, C., and Phillips, D. (2010) “Labor Supply and Taxes.” In A. Stuart (ed.), Dimensions of Tax Design: The Mirrlees Review. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mirrlees, J. A. (1971) “An Exploration in the Theory of Optimum Income Taxation.” Review of Economic Studies 38 (2): 175–208.

Neumark, D., and Shirley, P. (2020) “The Long-Run Effects of the Earned Income Tax Credit on Women’s Labor Market Outcomes.” Labour Economics 66: 101878.

OECD (2004) “Employment Protection Regulation and Labour Market Performance.” Chap. 2 in OECD Employment Outlook 2004.

__________ (2019) Tax Morale: What Drives People and Businesses to Pay Tax? Paris: OECD.

Planas, C.; Roeger, W.; and Rossi, A. (2003) “How Much Has Labor Taxation Contributed to European Structural Unemployment?” European Economy Economic Papers 2008–2015, No. 183. Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), European Commission.

Ramsey, F. (1927) “A Contribution to the Theory of Taxation.” Economic Journal 37 (145): 47.

Rosen, H. (1979) “What Is Labor Supply and Do Taxes Affect It?” NBER Working Paper No. 411.

Schoefer, B. (2010) “Regulation and Taxation: A Complementarity.” Journal of Comparative Economics 38 (4): 381–94.

Stern, N. (1986) “On the Specification of Labor Supply Functions.” In R. Blundell and I. Walker (eds.), Unemployment, Search and Labor Supply, 143–89. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Stockhammer, E. (2013) “Why Have Wage Shares Fallen? A Panel Analysis of the Determinants of Functional Income Distribution.” Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 35, ILO.

__________ (2017) “Determinants of the Wage Share: A Panel Analysis of Advanced and Developing Economies.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 55 (1): 3–33.

Triest, R. (1990) “The Effect of Income Taxation on Labor Supply in the United States.” Journal of Human Resources (Summer): 491–516.

World Economic Forum (2014) Global Competitiveness Report 2014–2015, Chap. 1.3: “The Executive Opinion Survey: The Voice of the Business Community.” Davos, Switzerland: World Economic Forum. (For the full report and a list of “pillar” questions, see http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalCompetitivenessReport_2014-15.pdf.)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.