The GameStop stock trading episode that began in January 2021 has been unprecedented in some ways, especially in the ability of market participants to organize collective action openly yet anonymously. In other ways, it’s been an unsurprising repetition of past experience. Financial markets are imperfect, they display many frictions, and the imperfect alignment of interests is a perpetual dilemma in designing both contracts and public policy.

The GameStop episode goes to the heart of many regulatory issues in finance. It provoked a flurry of reactions from politicians and regulators, including statements of concern, proposals for new laws and regulations, and investigations of potential wrongdoing, all suffused with expressions of hostility directed at “market manipulation” and speculators, characterizing the financial markets as a “rigged game” or “casino.”

Contrary to the cliché of an unregulated and predatory financial system, the actions of the participants and the events themselves shine a light on a remarkably dense array of regulations already in place. But much of today’s regulation makes markets function worse, not better, for investors. Much of the reactive call for investigations into wrongdoing and additional regulation was noteworthy for its vagueness. And much of the uproar has reflected a long-standing combination of paternalism, bad advice, and confidence in experts that misleads investors. The GameStop episode has also been just one manifestation among many of financial market buoyancy sustained by low interest rates.

GameStop and Robinhood in Early 2021

GameStop Corp. (GME) is a brick-and-mortar retail video game vendor chain that had its initial public offering in early 2002. By 2021 it was a troubled firm, with steadily falling share prices. It had been closing stores for some time, and the pandemic accelerated its sales decline. A 2019 attempt to find a buyer for the firm failed, and it terminated its dividend. Positions in the stock were concentrated, with a large amount held by active and activist professional investors. A venture capital firm with online retailing experience, RC Ventures, gained a board seat on August 30, 2020.

GameStop Goes Crazy in an Interesting Way

Short positions became a widespread play in 2020, particularly following a fragile late 2020–early 2021 share price recovery. GME became among the most widely shorted U.S. companies, 140 percent as measured by the ratio of short interest to shares available for trading. GME was one of a number of stocks in which long-short hedge funds took heavy short positions, among them so-called meme stocks popular with retail investors. Outstanding shares in institutional hands were largely pledged, and markets were increasingly alert to the possibility of a short squeeze.

From January 13, 2021, GME shares saw a sudden and drastic increase in price and in return volatility. The run-up was reported to have been led by a large increase in trading by retail investors using the Robinhood Financial platform, organized via social media, in particular the WallStreetBets chat forum on Reddit.

Robinhood imposed trading restrictions on January 28–29, barring new long positions in GME and a few other stocks while continuing to permit unwinding of existing positions. This triggered a furious uproar among its customers and in the press, and many politicians also voiced outrage.

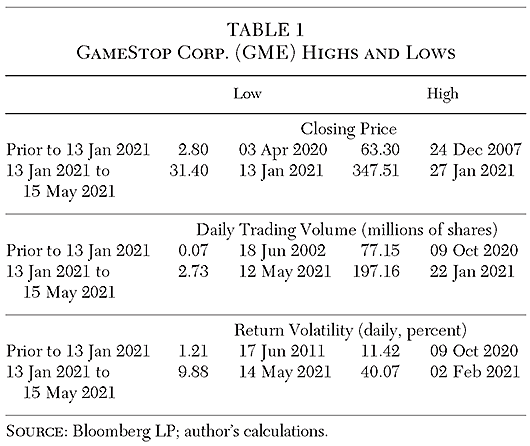

The stock retreated sharply from its late-January high, but then rebounded. GME return volatility remains extraordinarily high and its price much higher as of mid-May 2021 than before January 13 (Table 1).

Background: The Rise of Low-Cost Trading Platforms

Robinhood is a relatively new entrant into the highly competitive retail investing market, offering commission-free trades of stocks and exchange-traded funds since March 2015. It appeals to a young demographic drawn to trading via a relatively simple mobile app and playful devices for making trading attractive, such as the firm’s name and digital displays of confetti upon some customer actions.

Robinhood is heir to a half-century evolution making equity trading cheap and accessible to the nonprofessional public in the United States and other countries. Before 1970, individuals and households that weren’t wealthy invested in stocks mainly via pension claims and insurance products, rather than direct ownership of stocks and through mutual funds.

From the mid-1970s, changes in regulation, technical progress, rising wealth, and better understanding of long-term investing brought about a shift. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) abolished fixed stock trading commissions on May 1, 1975. Ownership of stocks has risen rapidly and equity mutual fund ownership even faster (Duca 2005).

Households and individuals now not only invest directly but are also more frequent traders. Nonprofessional investing has grown as a share of trading volume. Discount brokerages such as Charles Schwab, E*Trade, and Ameritrade arose in the 1970s to serve the retail market. More recently, retail investors have become part of the rapid growth in equity option trading.1

As brokerage volumes grew, low- and eventually zero-commission online stock trading became feasible. Index funds, which first appeared in the 1970s, were particularly cost efficient. The introduction and widespread adoption of electronic trading further massively cheapened trading. Zero-fee mutual funds and exchange traded funds (ETFs) followed, and recently, brokerages have begun offering zero-commission stock trading. Robinhood is a market innovator in this process.

The move to zero-fee and zero-commission trading has been enabled by a shift in the sources of brokerage revenue. The decline in trading fees and commissions is offset by net interest on customers’ cash balances, stock lending fees, and payment for order flow (PFOF) by wholesale market makers that execute the trades.

Legislative and Regulatory Actions

Regulators had cast a suspicious eye on Robinhood for some time. The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) had fined it in 2019 for failing to fulfill its obligation of “best execution” of trades, a charge closely related to PFOF. Robinhood’s platform had experienced service interruptions during the early pandemic period of high stock market volatility in March 2020, leading to investigations by the SEC, FINRA, and authorities in several states. Massachusetts’ chief securities regulator had brought a consumer protection suit on December 16, 2020. It alleged that Robinhood had been providing financial advice through its efforts to make its platform attractive to users, without subjecting itself to the legal duties of a financial advisor and failing to maintain an adequate infrastructure.2 Robinhood had on December 17, 2020, settled an SEC complaint, alleging its failure to fulfill an obligation to disclose PFOF to clients, and to satisfy a duty of best execution. A number of individual customers had also sued Robinhood.

The trading restrictions Robinhood imposed on January 28, 2021, were a turning point, bringing wider political scrutiny on it and other financial intermediaries. The SEC initiated new probes into the trading restrictions the next day. Regulators and legislators also focused on the GameStop episode and more broadly on retail investing.3 The Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) held an informal meeting to discuss GameStop on February 4. The House Financial Services and Senate Banking Committees held public hearings in February, March, and May, summoning a Robinhood founder, an investor active on Reddit, the head of Citadel Securities, a market maker making PFOF to Robinhood, and others to testify. The SEC chairman testified that it was considering new rules governing retail investing apps and PFOF.

Public Policy and Regulatory Questions

A key background factor in the GameStop episode is the low level of interest rates and associated very high degree of leverage in the United States and the world. Long and short GameStop positions are financed in large part with borrowed funds, or expressed through options, which have embedded leverage.

Impact of Low Interest Rates

Leverage becomes more attractive with near-zero short-term rates, as has been the case since 2008. Changes in the underlying asset price have an amplified impact on both profits and losses of leveraged positions, and relatively small changes in price bring about large changes in the rate of return on the investor’s equity. Leverage also adds a limited liability floor under losses. Investors with long positions financed with borrowed funds or long option positions can lose at most their own equity.

It’s not surprising, then, that there’s been a steady increase in leverage since the advent of the low-rate and low-inflation environment. The unobservable natural rate of interest, or inflation-adjusted equilibrium rate, has been very low, as a result of low expectations of both future economic growth and inflation.4 Borrowing costs as well as hurdle rates or required returns are thus very low by historical standards.

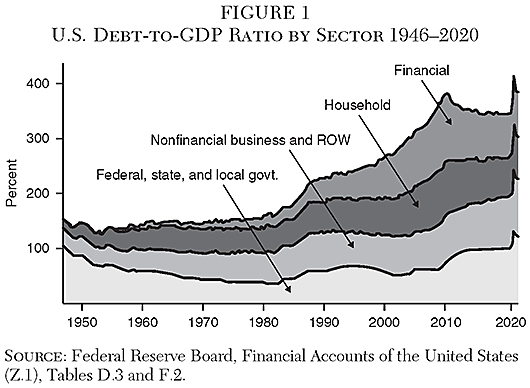

There had been a steady increase in the ratio of debt to GDP in the United States prior to the crisis, led primarily by households and the financial sector. Since 2008, the increase has continued, now as a result of large-scale borrowing by the federal government and nonfinancial corporate sectors, and, most recently, the sharp increase associated with the Covid pandemic.

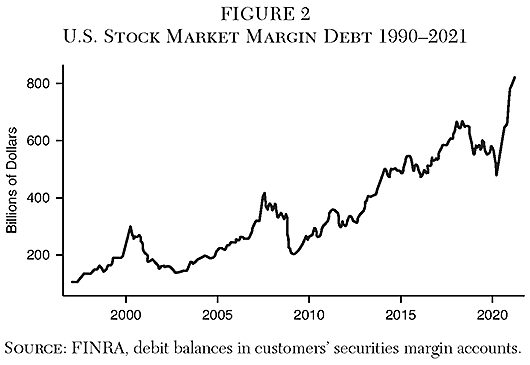

The U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio, at near 400 percent, is currently more than double what it was in 1980, and well above its previous peak during the global financial crisis (Figure 1).5 There has been a steady increase in stock margin for years, and its rate of growth has accelerated in the past year (Figure 2). The appetite of option sellers and buyers for the risk-return profiles and the embedded leverage of options and other derivatives is also increased by low rates.

Low interest rates provide incentives for higher leverage, but, in the United States and much of the rest of the world, lenders to banks and other financial intermediaries also enjoy implicit and explicit public guarantees that their debts will be repaid. The guarantees enable them to lever up more and take greater asset risks than they could otherwise get away with. The result is suppressed volatility, buoyant asset prices, rising option trading volumes, and an assessment by market participants that large losses are unlikely. The leveraged exposure is ultimately shared by the public (see Lee, Lee, and Coldiron 2019; Malz 2019).

This background contributes mightily to phenomena like the GameStop episode, and to the sense among inexperienced investors that return risk is low. More broadly, near-zero rates foster misallocation of resources, thwart reallocation, and destabilize the financial system. Firms that couldn’t compete in a higher-return environment can emerge and survive. GameStop may well have been underpriced prior to January 13, 2021, but the episode must also be seen in the context of reaching for yield and the flood of resources into private equity, reverse mergers, and Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs). The collapse of Archegos Capital Management, a family investment office employing total return swaps to gain equity exposure, is another recent example of leverage risk and the eagerness of banks to intermediate it through derivatives.

Market Efficiency, Market Manipulation, and Short Selling

The GameStop episode is difficult to reconcile with the “purist” market efficiency viewpoint—held by precisely no one—that market prices of assets reflect and reveal all available information about future value and cash flows (“fundamental value”) at all times. But there are more nuanced views that allow for the messiness of financial markets in the imperfect and friction-ridden real world. GameStop’s exceptional return volatility has been attributed to market frictions, limitations on position-taking due to regulation, risk management or investor tastes, unusually deep disagreement among investors, and social influences. The episode may reflect all of these. It’s also been decried—and defended—as an instance of market manipulation.

Market frictions include a range of impediments to instantaneous, smooth arbitrage. Market functioning overall was not severely impaired during the episode, but evidence of incomplete arbitrage surfaced between exchange traded funds and underlying stocks. Unusually large and persistent gaps opened at times between the State Street–sponsored SPDR S&P Retail ETF (XRT), of which GameStop had become the largest constituent, and its underlying basket.

Trading motivations are often classified into a simple dichotomy between informed and uninformed, with the latter labeled somewhat dismissively as “noise traders.” Some traders are termed well-informed because they’re privy to investment research or inside information not yet filtered into prices. Others, retail and institutional, are less informed but have good reasons to trade, such as asset allocation, hedging, or mimicking an index. Still other retail traders—and Robinhood investors are viewed as belonging to this group—may trade as a leisure activity or for emotional satisfaction, but not just in response to information or “rationally.”

Prior to January 13, 2021, there was sharp disagreement about the company’s ability to survive and grow. The analysis of the short investors was that GameStop was doomed, a brick-and-mortar retail relic that, especially after the Covid pandemic, had no prospects. The analysis of some long investors was that GameStop was undervalued and salvageable, and that it would eventually be bought and reorganized.6

The initial run-up in GME’s price may have been due to forced exits from short positions and long positioning by professional investors. This is hard to assess, since their position sizes and those of younger, less-experienced retail investors are unknown. Once the online promotion of GameStop gathered steam, the prevalence of uninformed investors may have also deterred better-informed investors in the short term.

U.S. financial regulation includes many restrictions on market manipulation or, in European regulatory parlance, abuse. The term is vague and has no uniformly accepted analytical or legal definition, apart from agreement on its blameworthiness (Fox, Glosten, and Rauterberg 2018). The SEC refers to elements including fraud, deception, and an “artificial price.”

The reaction to GameStop’s volatility has included a hunt for insider trading and suspicion of a “pump and dump” scheme—that is, collusion by an inside group to buy an illiquid stock, drive up its price, disseminate positive disinformation, and then sell quietly at the pumped-up price. In the GME case, the collusion departed in two important ways from prior experiences or suspicions of concerted, planned trading activity. The effort, crowdsourced via Reddit, was public, yet anonymous, so it’s difficult to identify specific individuals involved. This represents a new and quite efficient mechanism for organizing and synchronizing collective action.7 And it expressed sentimental as well as return objectives, mainly a desire to impose losses on hedge funds and other finance industry villains.

The WallStreetBets investors in GameStop primarily expressed hostility to short selling, in which shares are borrowed and then sold in the expectation of repurchasing them later at a lower price. The shares are then returned to their lender. Fierce hostility to short positioning as a form of market manipulation has been prevalent since its advent. In the United States, short positioning is generally permitted, but there are restrictions, especially on naked shorts. The SEC’s Regulation SHO limits naked shorting by requiring a broker or dealer to borrow shares or reasonably expect to locate a borrow before filling a short sale order. It also requires exchanges to impose price triggers or “circuit breakers” to halt shorting in declining markets. The SEC is now contemplating stricter disclosure rules for short positions.

When short selling is constrained by regulation, market participation becomes lopsided toward optimism, and mispricing can persist longer. Short sellers also improve corporate governance, helping discipline managers in a world in which their incentives can’t be perfectly aligned with those of shareholders (Caby 2020). In some cases—notably that of Enron in 2001 and more recently startup electric-truck manufacturer Nikola Corp.—investors with short positions have drawn attention to actual or possible management malfeasance.

Restrictions on short selling may have contributed to the rapid rise in GME’s price as well as volatility. If investors disagree sharply, but optimists are better represented in market prices because of short-selling constraints, both optimists and pessimists about GameStop will have an incentive to hold the stock at a high price, the former to realize its value, the latter in the hope of selling it to the former at an even higher price. The result would be both overvaluation and high trading volume. The startlingly sharp increase in GameStop trading volume provides some evidence (Lamont 2012).8

Regulation of Trading Infrastructure and Execution

Hostility to shorting is just one example of hostility to financial market trading generally. Another area drawing scrutiny and ire is financial trading infrastructure, the complex organization of trading, heavily regulated in the United States by the SEC and “self-regulated” by FINRA.

Brokers and dealers facilitate trading. Dealers (i.e., market makers or liquidity providers) quote bid prices to buy and offers to sell specific amounts of a security. They take principal positions, bearing the market and credit risk, and are compensated by bid-offer spreads. Brokers facilitate trades and provide trading infrastructure without taking positions and are compensated through fees, commissions, and payment for order flow by dealers. Robinhood Financial is an “introducing” broker in FINRA’s terminology, operating the platform account holders trade on. Orders are subsequently routed to external market makers for execution.

Stock trading in the United States was once heavily concentrated in a few exchanges, but today it is highly fragmented—executed on exchanges, Alternative Trading Systems (ATS) or “dark pools,” and by other market makers. All are registered with the SEC and report executed trade data, but are regulated differently. Exchanges are obliged to make bids and offers public through the National Best Bid and Offer (NBBO) system, and under the SEC’s 2005 Regulation NMS (RegNMS), to send arriving orders to the exchange displaying the best price. Other market makers are required to report trades only after execution (Stoll 2006).

Robinhood had come under scrutiny for its March 2020 outage, but its platform and those of other retail brokers held up during the January–February 2021 trading surge. The aspect of trade execution drawing the greatest scrutiny was PFOF flowing to it from ATS and other market makers.

PFOF is controversial and widely despised. It raises questions about conflicts of interest, especially the suspicion of “front running,” that is, market makers executing their own positions against those of retail investors, and not at the best prices. It also raises suspicions of collusion between payers and recipients of PFOF. However, the additional order flow increases market makers’ ability to aggregate orders and thereby improve moment-to-moment market liquidity for specific stocks.

The payments are a primary source of revenue for brokers offering zero-fee trading. PFOF is one cog in the elaborate machine that delivers low-cost trading to investors. The machine has to be paid for. It runs in a regulatory environment that ordains public sharing of prices by exchanges, but not other market makers, and a fragmentation of the market into a large number of exchanges and even larger number of ATS. Market makers, including the dark pools and high-frequency traders, want to scale up for efficiency while avoiding adverse selection by informed traders. They can do so with the addition of institutional and retail trading activity, including such noise traders as novice zero-commission Robinhood customers (see Shleifer and Summers 1990; Pirrong 2014).9

The opportunity to front run is just one incentive to market makers to scale up their order books, permitting overall trading costs to decline sharply over the past few decades. If market makers are to minimize principal risk, and commissions are zero, then the cost of providing liquidity has to come primarily from bid-ask spreads. If spreads have to be wider in the presence of informed traders, to compensate for the risk of adverse selection, less-informed traders who can be “picked off” by the market makers and information on order flows help narrow spreads. The market makers are intermediating; the trading gains go to the well-informed at the expense of the less-informed as the market is kept at a limited-arbitrage price near that which a perfect market would find. Retail can’t get “best execution” at all times; it just wouldn’t add up.

Looking at this from an “either at the table or on the menu” point of view is too simplistic, analogous to seeing Google search users solely as victims because data on their activity are provided to advertisers, rather than as engaged in an exchange. Slightly inferior execution due to PFOF is an indirect offset to lower commissions and fees than in the past. Bid-offer spreads have to be narrow enough to attract flow, and wide enough to compensate for the dealer’s risk. A market maker more reliant on informed flow will widen spreads.

This process of equating share supply and demand over time takes place in a market that is currently fragmented by regulatory design. An alternative, less-regulated, but more efficient market place can be imagined, if not predicted, in which marketplaces are more concentrated, PFOF is less prevalent, retail investors pay for trades more explicitly, and overall transactions costs are lower.

PFOF is one of many examples in finance of the principal-agent problem, in which there are conflicts of interest, but mutual benefits as well that far outweigh the costs of not mitigating those conflicts entirely. The resulting configuration reduces trading costs, albeit within a system that imposes through regulation costly fragmentation and differential disclosure obligations on market makers. Everyone gains from cheaper trading, including uninformed Robinhood customers and less well-informed but fully rational investors adjusting their asset allocations or reaping capital gains and losses for tax purposes, even if they are “picked off” by the dealers.

Some advocates of restrictions on PFOF also propose a transactions tax on trading. Supporters claim it would not only raise revenue but also curb speculation and dampen short-term market volatility without impairing liquidity or market efficiency. It would dovetail with restrictions on PFOF by countering the zero-commission impetus to frequent trading by retail investors. Such a tax is likely, however, to impair liquidity and make arbitrage and risky efforts to align price and value more costly.10

Procyclicality: Margin Rules and Option Trading

Several steps are required following execution to complete a trade. The first is clearing, in which counterparties confirm the price, quantity, and other terms with one another. The next is settlement, in which the securities are transferred and final payment made. Stocks in the United States have a two-day settlement period (“T+2”), during which the National Securities Clearing Corporation (NSCC) transfers security entitlements, a form of ownership, to the buyer and cash to the seller. The NSCC becomes the counterparty to both sides of each stock trade, with a net position of zero, in principle, in each transaction, in each stock, and in cash.

Settlement risk events occur when a party to a trade fails to complete its side of settlement. The broker, not the customer, has the liability vis-à-vis the clearing house for stock price risk during the settlement period and is therefore required to post margin in an NSCC clearing fund account. Margin is calculated using Value-at-Risk (VaR), which incorporates the risk of ordinary fluctuations in price, and a Gap Risk Measure, which incorporates the risk of extraordinary changes in price.

By the end of January, Robinhood Securities, Robinhood’s clearing subsidiary and a member of the NSCC, had a very large net long position in GME and a few other stocks. If Robinhood were to fail or deliver insufficient cash to the clearing house, the NSCC wouldn’t have cash to deliver to the sellers, while still being obliged to transfer security entitlements to Robinhood customers. GameStop had a 235 percent change in price, and Robinhood Securities had a large net change in clearing position on January 27 and was reportedly subjected to a $3.4 billion margin call on January 28.

Robinhood then “restricted transactions for certain securities [including GME] to position closing only.”11 GME liquidations in customer accounts would reduce Robinhood’s required margin with the NSCC, while additional longs or shorts in most other stocks wouldn’t drastically change margin, and were not restricted. With the new restrictions in place, the margin call was reduced to less than $1 billion. Speculation was widespread that Robinhood announced these restrictions in collusion with or at the behest of hedge funds unwinding short positions or other financial firms. Robinhood was obliged to quickly raise new funding on what appear to have been unfavorable terms, including cheaply priced claims on future share issues.12

The NSCC margin rules compelling Robinhood’s actions were designed to conform to the Dodd-Frank Act’s regulatory mandates. Dodd-Frank intended to enhance financial stability by promoting clearing systems with near-zero credit risk to participants. The regulations, which were formulated with the full cooperation of the industry, are potentially destabilizing. Sharply higher margin may force position liquidations or “fire sales,” including other asset positions, increasing volatility and spreading the impact to other markets. An episode of this kind took place in March 2020 in U.S. Treasury markets, triggered by similar mandated margining rules in futures markets.13

The GameStop episode has been associated with a similar late-January increase in volatility in the broader market. January 27 was the peak of a wave of liquidations by long-short hedge funds of widely shorted stock positions, including GME and other meme stocks, and their offsetting longs (Goldman Sachs 2021). Internal risk control mechanisms that close losing short positions “without appeal,” such as stop-loss orders and limits based on VaR, may have forced some traders out, even though they had lost none of their conviction about GameStop’s bleak future.

It is difficult to identify the impact of exits from GameStop among other contributors to higher volatility, but some evidence for its influence is the unusual sharply negative correlation between GME returns and those of the market during January−February 2021.14 It indicates that forced liquidations of GameStop and other heavily shorted stocks as risk-management thresholds were crossed may have spilled over into markets for other stocks. As GameStop rose, some investors would have had to sell other liquid assets to fund margin calls and the return of cash collateral against the short positions they exited.

A large volume of positions in GME were expressed via options, which together with their associated hedging likely also contributed to volatility. Option dealers, often the broker-dealer subsidiaries of too-big-to-fail banks, are generally net sellers of call and put options in large volumes to earn a narrow volatility premium. They hedge by buying the underlying stock when its price is rising and selling when it is falling. Large changes in the underlying price force dealers to buy or sell in the worst market conditions and expose them to heavy losses. GME’s rapidly rising price would have forced dealers who had sold call and put options to retail and professional investors to buy GameStop stock in an effort to contain losses and maintain a hedged position.

Consumer Protection and the Social Psychology of Young Investors

The social psychology of Robinhood’s customers isn’t surprising in a time of diffuse hostility, a mood of generalized rejection and opposition, and the emergence of social media. It contains a strong political undertone focused on many objects apart from the finance industry.

“Gamification” refers to platforms’ use of light-hearted gimmicks to engage customers and encourage activity with which Robinhood particularly distinguishes itself from competitors. It appeals to the conviction among many younger traders that financial markets are a rigged casino, blending it with the popular pastime of video gaming. It’s not entirely dissimilar to the enthusiasm for bitcoin—and not entirely alien even to libertarians—substituting hostility to Wall Street for distrust of fiat currency, and focused not on avoidance but retaliation, participating in the rigged game to seize a just share of the ill-gotten gains.15

Consumer protection is an old part of the finance regulatory apparatus, dating back to the New Deal. In recent years, much of the focus has been on consumer lending practices as well as on investment management and the regulation of “investment advice.” The latter focuses primarily on eliminating some of the inherent conflicts of interest between households and the professionals involved in their investments. The focus in the GameStop episode has been on protecting young investors from the behavioral stimuli said to be embedded in trading apps in order to encourage frequent trading and earn PFOF.

Some actions against Robinhood, such as that by Massachusetts, have been based on provision of investment advice and on preventing customer funds from misuse under the SEC’s Customer Protection Rule 15c3‑3. Younger investors have been treated by many politicians as a new source of “dumb money,” drawn in by zero-cost trading. Even more than other investors, they must be protected from their own bad decisionmaking, and from misleading advertising (e.g., Robinhood’s confetti).16 Robinhood’s defense has been that it is not a financial advisor, but only a broker and platform operator.

But it’s not clear these fears are warranted. For one thing, the relative position sizes of younger retail, professional, and other investor groups are unknown. Evidence on retail investment performance is mixed, but in some respects positive, especially by comparison with active professional investment managers. Retail investors have a good track record of holding steady rather than panic-selling during market downturns. For example, during the March 2020 Covid-19 downturn, Robinhood investors avoided panic selling and, in fact, increased holdings, outperforming the broader market (Welch 2020). The typical performance of activist investors is terrible. One of the few activist characteristics that seems to actually reap higher returns over benchmarks is patience, a characteristic many individual investors appear to share with them (Cremers and Pareek 2016).

But there is also evidence that Robinhood’s customers, who are distinct from the broader retail investing population, are in good part uninformed (Barber 2021), thereby diminishing liquidity and providing opportunities for market makers. High-frequency traders (HFTs) withdrew during Robinhood platform outages, a clue that Robinhood traders are uninformed, since HFTs anticipate losing money when they are trading primarily with better-informed counterparties (Eaton et al. 2021).

Paternalism and Public-Sector Investment Advice

The mindset of the Robinhood investor base seems immature and needing protection to many consumer advocates and politicians. But it’s not that different from the well-established regulatory view that the entire system of investing is unfair and that only professionals in the industry can succeed at it. Ordinary investors, outsiders, are misled and impeded by the finance industry from obtaining the “special” information needed to invest successfully. But nothing could be further from the truth than the view that the typical successful investor “beats the market,” trading frequently on superior information.

The government and consumer-advocacy view of investment and wealth building is largely implicit, but expressed in many ways, including the approach to consumer protection, encouragement and validation of active investment management, retirement savings policy, and taxpayer support of homeownership. All are replete with paternalism and harmful in their message or incentives. Sound investment advice emphasizing saving, diversification, a long-term perspective, and attentiveness to investment costs and taxes is conspicuous by its absence.

The consumer-protection regulatory strategy is to identify and expunge all conflicts of interest. Then retail investors will have the same accurate information and engage in stock picking on an equal footing with the pros. The goal is “democratizing access to the financial markets and creating a level playing field for everyday investors” (Kelleher and Cisewski 2021). The fullest expression of the approach was the attack on the organization of equity analysis in investment banking. It was led by the SEC and New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, among many other public officials, supported by newspaper commentators and elected officials, and culminated in a series of settlements in 2002 and 2003.17

Federal and local governments provide for retirement through Social Security and public defined-benefit pension plans and encourage private pension funds and individual retirement accounts through tax and other policies. Social Security and defined-benefit plans are presented as a silver bullet for retirement income, but have adverse effects on saving, economic growth, and government finances, as well as raising conflict of interest problems. They haven’t resolved retirement income uncertainty for many beneficiaries.

Simple individual retirement accounts, untaxed at the time of contributions and withdrawals—akin to consumption taxation—would reward saving. Instead, the bewildering complexity of current Federal tax policy vis-à-vis individual retirement accounts, its rules and penalties on contributions and withdrawals, adds to savings reluctance. Policymakers for the most part see myopia rather than incentives as the source of that reluctance and prescribe various behavioral nudges, such as automatic enrollment, to offset it. In aggregate, these measures discourage rather than encourage saving. Viewed as a whole, the policy is inherently contradictory: provide the future benefits, but maintain current tax revenue, rendering its financing economically difficult.

Paternalism is also reflected in advocacy of defined-benefit plans. It emphasizes the value of professional investment management as a key advantage, neglecting the now well-established shift by nonprofessional investors toward lower-fee passive investing and away from active management.18

The vast system of encouragement of home ownership is another example of bad government investing advice and disincentives to saving. For the better part of a century, real-estate ownership has been fostered as the fulfilment of the American Dream by tax subsidies; public and publicly guaranteed lenders; unceasing promotion by officials as the core, if not sole constituent of any wise investor’s portfolio; and myriad local land-use regulations.

While home ownership can have advantages over renting, if prices are favorable and the home throws off enough intangible benefits, it has distinct disadvantages for many households. Real-estate is illiquid: it is costly to buy or sell a home, reducing mobility and the ability to adapt when the location of business and employment opportunities changes. It becomes even more illiquid and house prices stagnate or decline when business conditions are bad and the benefits of moving are greatest. The location of a home presents idiosyncratic risk. Housing is lumpy: you can’t sell part of it to meet smaller needs. And it keeps most homeowners with an undiversified, leveraged portfolio consisting largely if not exclusively of a single nonearning asset.

Conclusion

Whatever the cognitive state of the Robinhood customer base, the current regulatory stance has amounted to bad advice from the government about investing—ignoring some basic truths. It is good that investment transactions have become far less costly for nonprofessionals. It is good to get younger people beginning to invest earlier in their lifetimes. But there is some bad guidance from the public sector out there.

The reigning mindset among regulators and politicians embeds just about the worst possible advice for younger investors. Financial education is not primarily, if at all, a government responsibility. But government contributes heavily to conveying the wrong messages. Most of what regulators deem investment advice is provided to customers of active managers, who are either openly charging commissions or acting as “fiduciaries.” The costs to these investors of the conflicts of interest, real or putative, are trivial compared to the returns they forfeit by not avoiding active management altogether, by looking for the “honest” and “superior” manager who can beat the market, and by engaging in market timing. One wishes that, if the government can’t say “start young, think long-term, save, diversify, lean toward equities, understand your own situation, and take advantage of the tax code,” it would please not say anything at all about personal investing.

It’s interesting to note that, in the aftermath of the initial GME run-up, the outcry was less for the introduction of specific new regulatory or legislative measures. Rather, it focused on the need for investigations and “scrutiny” of Wall Street. The focus was on cheating, conflicts of interest, and manipulation. But a message of distrust with no solutions apart from the Reddit solution—consumers, get in on the rigged game!—is no solution at all. The real solution lies in liquid markets that are cheap to invest in and people, especially the young, who are better informed about investing, not the targets of political manipulation. That stands a better chance of equipping people to scrutinize the finance industry with more discerning eyes.

References

Barber, B. M. (2021) “Attention Induced Trading and Returns: Evidence from Robinhood Users.” Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3715077.

Burman, L. E.; Gale, W. G.; Gault, S.; Kim, B.; Nunns, J.; and Rosenthal, S. (2016) “Financial Transaction Taxes in Theory and Practice.” National Tax Journal 69 (1): 171–216.

Caby, J. (2020) “The Impact of Short Selling on Firms: An Empirical Literature Review.” Journal of Business Accounting and Finance Perspectives 2 (3): 1–9.

Cochrane, J. H. (2013) “Finance: Function Matters, Not Size.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27 (2): 29–50.

__________ (2021) “Portfolios for Long-Term Investors.” Available at www.johnhcochrane.com/research-all/long-term-portfolios.

Cremers, M., and Pareek, A. (2016) “Patient Capital Outperformance: The Investment Skill of High Active Share Managers Who Trade Infrequently.” Journal of Financial Economics 122 (2): 288–306.

Duca, J. V. (2005). “Why Have U.S. Households Increasingly Relied on Mutual Funds to Own Equity?” Review of Income and Wealth 51(3): 375–96.

Eaton, G. W.; Green, T. C.; Roseman, B. S.; and Wu, Y. (2021) “Zero-Commission Individual Investors, High Frequency Traders, and Stock Market Quality.” Available at doi:10.2139/ssrn.3776874.

Fox, M. B.; Glosten, L. R.; and Rauterberg, G. V. (2018) “Stock Market Manipulation and Its Regulation.” Yale Journal on Regulation 35 (1): 67–126.

Goldman Sachs (2021) “The Short and Long of Recent Volatility.” Global Macro Research. Available at www.goldmansachs.com/insights/pages/the-short-and-long-of-recent-volatility.html.

Kelleher, D., and Cisewski, J. (2021) “Select Issues Raised by the Speculative Frenzy in GameStop and Other Stocks.” White Paper, Better Markets.

Lamont, O. A. (2012) “Go Down Fighting: Short Sellers vs. Firms.” Review of Asset Pricing Studies 2 (1): 1–30.

Lee, T.; Lee, J.; and Coldiron, K. (2019) The Rise of Carry. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Liang, N., and Parkinson, P. (2020) “Enhancing Liquidity of the U.S. Treasury Market under Stress.” Hutchins Center Working Paper, Brookings Institution.

Malz, A. M. (2019). “Macroprudential Policy, Leverage, and Bailouts.” Cato Journal 39 (3): 499–528.

Martin, K., and Wigglesworth, R. (2021) “Rise of the Retail Army: The Amateur Traders Transforming Markets.” Financial Times (March 9).

Pirrong, C. (2014) “Pick Your Poison: Fragmentation or Market Power? An Analysis of RegNMS, High Frequency Trading, and Securities Market Structure.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 26 (2): 8–14.

__________ (2020) “Apocalypse Averted: The COVID-Caused Liquidity Trap, Dodd-Frank, and the Fed.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 32 (4): 1–5.

Rudegeair, P.; Grind, K.; and Farrell, M. (2021) “Robinhood Raises $1 Billion to Meet Surging Cash Demands.” Wall Street Journal (February 5).

Shleifer, A., and Summers, L. H. (1990) “The Noise Trader Approach to Finance.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 4 (2): 19–33.

Stoll, H. R. (2006) “Electronic Trading in Stock Markets.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 20 (1): 153–74.

Welch, I. (2020) “The Wisdom of the Robinhood Crowd.” NBER Working Paper No. 27866.

Zuluaga, D. (2020) “Financial Transactions Taxes: Inaccessible and Expensive.” Cato Journal 40 (3): 613–24.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.