Economic growth in advanced economies is driven primarily by innovations that improve productivity. Entrepreneurs and researchers, who are motivated by economic incentives, generate new ideas that result in either new or expanded businesses. The resulting expansion of businesses generates new and better products and services. Entrepreneurs also change the way production is organized because they improve efficiency that lowers prices for consumers. Such actions produce economic growth, which manifests itself by increasing product variety, jobs, and wages. As a result, economic well-being increases (Alcigit and Kerr 2018; Jones 1995, 2016; McCloskey 2016; Romer 1990).

Immigrant entrepreneurs play a role in the economic growth process. Higher levels of immigration increase economic growth through an immigrant’s productive skills and innovation-related activities (Ortega and Peri 2014). Immigrants also account for a large share of patents in the United States. In addition, immigrants contribute to new businesses and tend to be more entrepreneurial than the average U.S. citizen (Kerr 2019).

Immigration is controversial because people have differing views about the effects that immigrants have on the economy and culture. This article focuses on the economic rather than cultural effects of immigration. Although it is unlikely that culture and the economy are unrelated, there is evidence that cultural diversity, when measured by the diversity of a country’s immigrants, raises native wages and the rental value of homes (Ottaviano and Peri 2006; and Nowrasteh and Powell 2021).

Some U.S. citizens are concerned that the increase in immigration may change the country’s national identity. Others view immigrants as being similar to themselves: immigrants are people trying to improve their life and economic circumstances. Political rhetoric intensifies such differences, thereby making immigration reform less likely. A look at polling data provides a sense of the divergent views that individuals have on immigration. Polling data in the United States suggest that people are generally divided over the effects of immigrants on the country.

A 2020 CBS News poll asked, “Generally, do you think immigrants coming to the United States make American society better in the long run, make American society worse in the long run, or you don’t think immigrants coming to the U.S. have much of an effect on American society one way or the other?” Among respondents, 55 percent said better, 16 percent said worse, and 20 percent said it did not have much effect (CBS News 2020).

A 2020 Gallup poll asked the question, “In your view, should immigration be kept at its present level, increased, or decreased?” Among respondents, 36 percent wanted to keep it at the present level, 34 percent thought it should increase, and 28 percent wanted it decreased. Whereas responses have fluctuated over time, the percentage of people who think the level of immigration should be increased equaled only 7 percent in the earliest poll taken in 1965. Respondents who thought it should be kept at the same level or decreased declined over the same period suggesting, at least until recently, that immigration appeared to be viewed more favorably (Gallup 2020).

Those polls suggest that people in the United States are divided about the costs and benefits of immigration. U.S. citizens should keep in mind that immigrants, especially high-skilled ones, start new businesses and play an important role in technological innovation—both of which help create jobs and raise wages for everyone. Immigrants help provide important services such as in health care (Lincicome 2020). The net benefits of immigration promote economic growth and well-being, thus expanding opportunities for both immigrants and native-born populations in the United States.

To better understand the effects of immigration on the economy, this article will provide basic data about immigration trends in the United States. The main body of the article will review the evidence from studies that examine the effects of immigration on entrepreneurship and innovation.

Immigrants in the United States

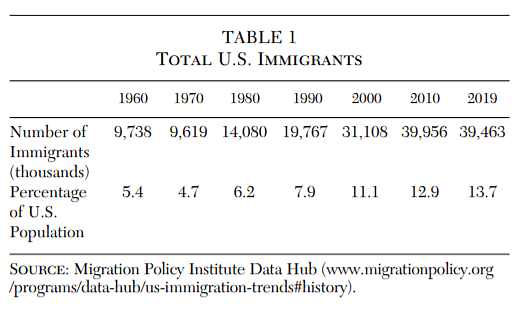

Immigrants are people living in the United States who were not U.S. citizens at birth. Immigrants include naturalized U.S. citizens, green-card holders, refugees, asylees, temporary visa holders, and unauthorized persons. Table 1 provides data about the total number of immigrants (measured in thousands). It also expresses the number as a percentage of the U.S. population between 1960 and 2019. Both measures have increased significantly over the period.

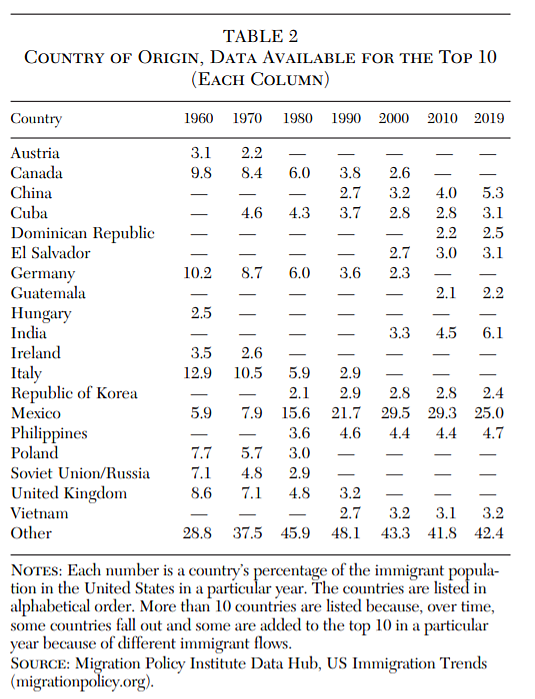

Table 2 provides a breakdown of immigration data by country of origin. For each country, if it was in the top 10 (by amount) for the years between 1960 and 2019, the table lists the percentage of total immigrants from that country in that year. For the years in which the country was not in the top 10, no data are reported. More than 10 countries are listed because, over time, countries in the top 10 in early years drop out and new countries enter the top 10. Two trends are apparent. First, European countries make up a larger portion of source countries in the earlier years but not in later years. Second, the share of total immigrants from Asia, Central America, and South America has increased over time. Unsurprisingly, Mexico captures the largest share by far in 1980 and beyond.

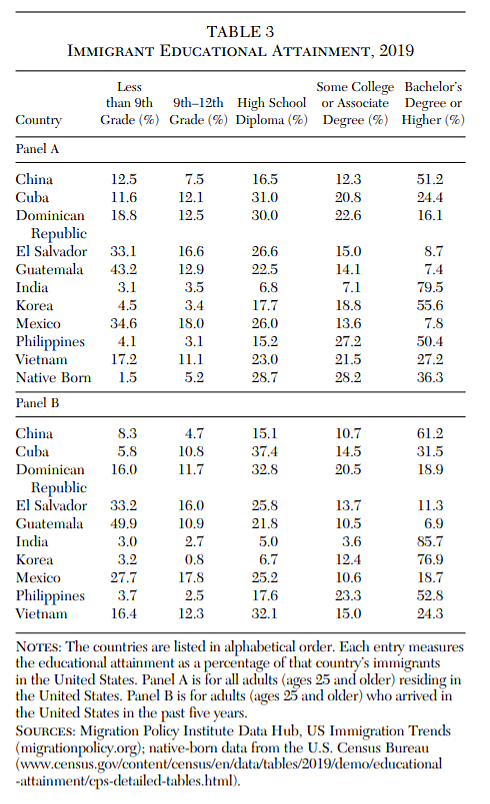

Table 3 provides the educational attainment level for immigrants from 10 countries with the largest share of immigration in 2019. Panel A looks at all immigrants, while Panel B looks at the same group of countries but for all the immigrants who came to the United States after 2013. The skill distribution of immigrants tends to have a U‑shape. Skill levels concentrate at the high and low ends of the distribution. We can see this concentration in Table 3. I calculate that, for all immigrants between 1960 and 2019, 26.3 percent had fewer than 12 years of education, whereas 32.7 percent had a bachelor’s degree or more (Panel A). For comparison, in 2019, 36.3 percent of native-born U.S. citizens had a bachelor’s degree or more, and 6.7 percent had not graduated from high school. Those percentages change for the more recent immigrants: 18.6 percent have fewer than 12 years of education whereas 47.9 percent have a bachelor’s degree or more (Panel B). The skill mix of immigrants as measured by education level has changed, with fewer unskilled workers and more skilled workers.

More than 85 percent of recent immigrants from India have a bachelor’s degree or more. Other countries that provide a large percentage of skilled labor include China and the Philippines. Moreover, Guatemala, Mexico, Vietnam, and the Dominican Republic provide the largest shares of unskilled labor.

The number of immigrants has increased both in absolute numbers and as a share of the U.S. population. Moreover, the countries of origin have shifted from Europe to Latin America and Asia. The share of higher-skilled immigrants has risen, while the share of lower-skilled immigrants has declined.

Immigration and Entrepreneurship

Data indicate the growth in entrepreneurship in the United States is slowing (Congressional Budget Office 2020). Decker et al. (2014) report that in recent decades the trend has been downward in the growth of business startups. The decline has accelerated since 2000. One way to offset this trend is to expand immigration, especially among higher-skilled entrepreneurial immigrants.

Fairlie et al. (2018, 2019) found that the average number of startups between 1995 and 2010 was 5.4 million per year, which represents about 25 percent of the total businesses in the United States. Such startups create about 3 million jobs in their startup year and employ 2.9 million workers five years later. These figures are comparable with those reported in Decker et al. (2014). The employment growth of the surviving firms more than offsets the job losses of firms that exit. In fact, without the additional jobs, aggregate U.S. employment growth would have been negative during this period.

Kerr and Kerr (2020) report that immigrants tend to be more entrepreneurial than the average U.S. citizen. The difference can be explained partly by the fact that an individual’s decision to emigrate is risky, much like starting a new business. Immigrants, by their nature, appear to be more tolerant of risk.

Immigrants may also be more likely to start their own business because they initially may face discrimination in the labor market (Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle 2010; Hunt 2011). The growing percentage of immigrants with college degrees in STEM fields may make them more inclined to develop new products and to start businesses than the average U.S. citizen (Azoulay et al. 2020; Brown et al. 2020; Kerr 2019; Kerr and Kerr 2020).

Two recent studies provide evidence about this issue. Azoulay et al. (2020) used data from the U.S. Census to examine business startups for the period 2005 to 2010. They found that the firm count per capita for immigrants is higher than for natives at all firm sizes. Using the Census Bureau’s Survey of Business Owners for 2012, the authors found that 7.25 percent of immigrants start firms compared with 4.03 percent of natives, nearly 80 percent higher. Wages at immigrant firms are 0.7 percent higher than at firms created by natives. Those immigrant-founded firms are also 35 percent more likely to have a patent. Looking at Fortune 500 businesses, immigrants have started more successful businesses than have natives.

Kerr and Kerr (2020) used the Census Bureau’s Survey of Business Owners and its Longitudinal Business Database for the period 2008 to 2012 to examine immigrant entrepreneurship. They found that first- and second-generation immigrants created approximately 40 percent of the Fortune 500 companies. They also found that first-generation immigrants created 25 percent of all new firms in the United States over the period examined.1 The Kerr and Kerr sample includes the Great Recession of 2008. There is evidence that startups increase during recessions as unemployed workers with limited job prospects are more likely to try starting a business as an alternative career option under those conditions (Fairlie 2013).

Startup business survival rates tend to be procyclical, which means survival rates tend to decline during recessions and rise during expansions. According to the Kauffman Foundation, since 2012, survival rates for all startups have been stable, fluctuating between 79.2 and 79.7 percent. The survival rate in 2009, during the Great Recession, equaled 75.3 percent (Fairlie and Desai 2020).

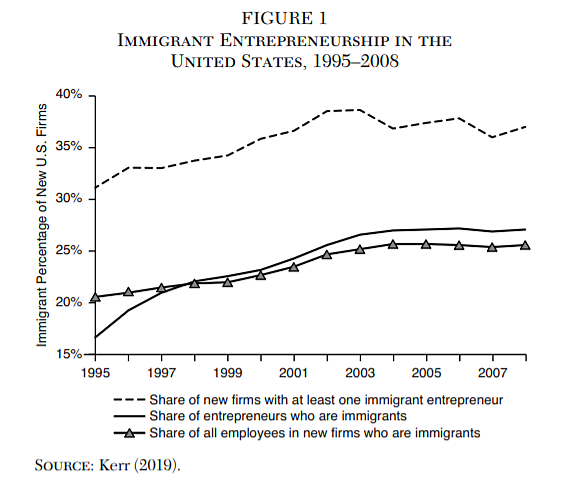

Kerr (2019) used data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics database to track immigrant entrepreneurship between 1995 and 2008. The data tracked three different trends, as seen in Figure 1. First, the new firm share of all employees who are immigrants increased from 16.7 percent in 1995 to 25.6 percent in 2008. Second, the share of entrepreneurs who are immigrants rose from 20.6 percent to 27.1 percent over the period. Thus, immigrants account for about 785,900 net jobs per year. Finally, the share of new firms with at least one immigrant entrepreneur grew from 31.1 percent in 1995 to 37.0 percent in 2008. These data show that immigrants are playing a growing entrepreneurial role in the U.S. economy by starting new businesses. They also capture a larger share of employment in new firms.

Kerr and Kerr (2020) provide a more detailed breakdown of immigrant entrepreneurs by sector and states. They compared the percentage of firms started by immigrants—either alone or working with natives—in both the high- and low-tech sectors. In 2007, that group of entrepreneurs started 24.8 percent and 23.6 percent of high- and low-tech firms, respectively. Those figures rose to 28.6 percent and 25.5 percent, respectively, in 2012. Kerr and Kerr also found that the industry composition of immigrant and native businesses is comparable with strictly native-owned firms. Although industry shares are not identical, immigrant and native firms do not appear to be disproportionally represented in highly cyclical industries. For example, in 2012, the share of native firms in construction equaled 13.4 percent, nearly double the 7.0 percent figure for immigrant and mixed businesses.

In some states such as California and New York, first- and second-generation immigrants created more than 40 percent of the new businesses over the period of 2008 to 2012. But there is a wide range at the state level. For example, first- and second-generation immigrants started only 5 percent of the new businesses in Idaho and North Dakota. Such differences reflect differences in the size of immigrant populations in those states. Immigrant businesses pay comparable wages but provide fewer benefits, such as 401K plans. Furthermore, immigrant firms are more engaged in international trade than are native startups. This engagement reflects a better understanding of foreign markets, especially in the countries they emigrated from.

In sum, immigrants tend to be entrepreneurial and to start a significant share of U.S. businesses. Those new firms also make a significant contribution to employment growth in the United States.

Immigration and Innovation

A growing body of research confirms that immigrants play an important role in innovation and improved business efficiency in the United States and abroad. For example, Hunt (2011) and Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle (2010) showed that immigrant graduates with science and engineering degrees had a patent rate double the average native rate for the period of 1940 to 2000. (When immigrant U.S. patent share is compared with natives of similar education, the difference is smaller.) They also pointed out that immigrants’ share of U.S. patents has increased significantly over the past 20 years. Using state-level U.S. data, Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle (2010) estimated that a 1 percent increase in immigrant college graduates as a share of the population increases the number of patents per capita by 9 to 18 percent.

However, the aging population in the United States will lead to a decline in business startups and innovation over time (Bloom et al. 2020; Jones 2020; Liang, Wang, and Lazear 2018). Expanding immigration can moderate those forces to help stabilize long-term economic growth. So, in addition to starting businesses—many of which are highly innovative—immigrants bring new ideas about potential new products and better ways to produce existing products or services.

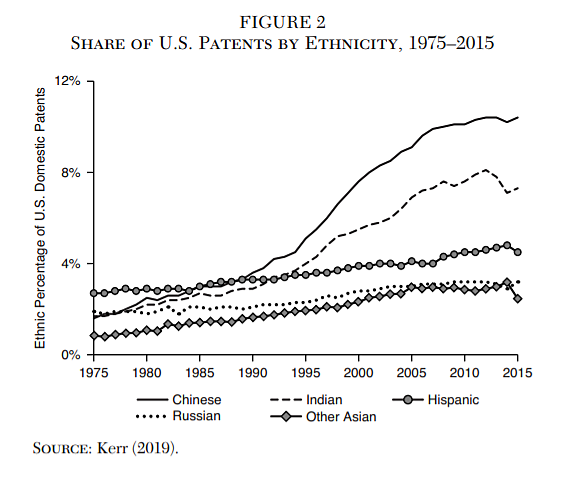

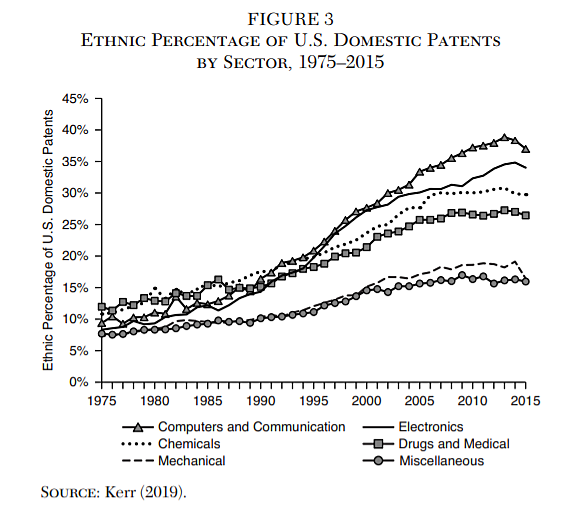

Kerr (2008, 2019) used a computer program that determines the ethnicity of a patent holder by using the person’s first and last name. Drawing on data from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, he was able to determine the ethnic composition of U.S. patents between 1975 and 2015. Figure 2 illustrates those results. Anglo-Saxon and European names captured 91 percent of U.S. patents in 1975. By 2015, that percentage declined to 72 percent. In 1975, names indicating Chinese and Indian ethnicity represented only 1.6 and 1.7 percent, respectively, of U.S. patents. However, they represented the largest increases over the period. By 2015, individuals with Chinese and Indian names captured 10.4 percent (a 6.5‑fold increase) and 7.3 percent (a 4.3‑fold increase), respectively, of all U.S. patents. This finding illustrates how immigrants are innovative and are important contributors to U.S. patents and innovation. Figure 3 shows the growing role played by immigrants in high-technology sectors that range from drugs and medical to computers and communication.

Bernstein et al. (2019) used a database that provides individual data for 160 million adults living in the United States. The data include the first five digits of the person’s Social Security number, as well as name, living addresses, year of birth, and gender. The first five digits allow the researchers to determine the year the individual got a Social Security number. Most natives get those numbers when they are born, when they are relatively young, or when they get their first job at age 16. Bernstein et al. identified immigrants as individuals who get their Social Security number in their 20s or later.2 The authors merged (linked) an individual’s immigration status determined in the first dataset with patent data from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Thus they found that 23 percent of all patents went to immigrants between 1976 and 2012. This number is 40 percent higher than their share of the U.S. inventor population. The high number of patent citations indicates that the patents tend to be of high quality.

Bernstein et al. (2019) also investigated the possibility of spillover effects from an increase in immigrant inventors over the productivity of native inventors. They estimated the impact of a collaborator’s premature death (i.e., before age 60) on the future productivity of the living collaborator. They found the death of an immigrant collaborator reduces the native inventor’s productivity (patents or patent citations) over time by 50 to 65 percent. If the premature death involves a native collaborator, the productivity of the immigrant inventor declines less, between 28 and 35 percent.

Not surprisingly, there are clear spillover benefits from research collaboration. However, on the basis of those estimates, native inventors appear to gain more. The spillover benefits are the result of effectively combining the different knowledge and experience that each inventor brings to any project. The larger influence of the immigrant collaborators may be due to their bringing to research projects a foreign or possibly larger global knowledge base that differs from that of the average native collaborator.

Peri, Shih, and Sparber (2015) showed that foreign-born STEM workers were associated with an increase in productivity and wages in a sample of 219 U.S. cities from 1990 to 2010. In addition, they estimated that increases in foreign STEM workers could explain between one-third and one-half of aggregate growth in total factor productivity in the United States during that period. They estimated that this finding translated into native per capita income’s being 10 percent higher in 2010.3

If immigrants have different complementary skills when compared with native workers, then, with immigration, native workers can specialize and can take on the tasks they are best at. The result would be an increase in efficiency and lower costs. For example, as immigration increases, native workers shift into jobs that are more language intensive (sales and management). Immigrants focus on jobs that require fewer language skills, such as programming or construction. This increase in skill diversity and greater specialization improves productivity.

Peri (2012) examined the effects of increased immigration on long-term productivity growth in the 50 states and Washington, D.C., in 1960, 2000, and 2006. He found that immigration raised state growth in total factor productivity. He estimated that between one-third and one-half of the productivity growth increase had been caused by improved (i.e., more efficient) specialization of job tasks related to the increase in immigration.

Research has also looked at the effects of immigration at the firm level. Creative destruction is an important way in which innovation promotes economic growth. Superior products, services, or production methods of a new entrant will replace those of older incumbent firms. Khanna and Lee (2018) found that a 10 percent increase in H‑1B (immigrant) workers results in a 2 percent increase in firm entry and exit (i.e., increased creative destruction) across a wide set of U.S. industrial sectors.

Brown et al. (2020) used data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs to compare the innovation activities of immigrants with those of natives in high-tech industries at the firm level. After controlling for demographic factors, startup financial resources, and specific industry, they found higher levels of innovative activities (e.g., new products and production techniques, higher R&D, more patents granted or pending) among immigrants than natives. Interestingly, despite higher levels of patents, the same data show that immigrants had fewer copyrights and trademarks, perhaps owing to the nature of the type of products (arts and marketing versus technology) for which copyrights and trademarks are sought. Those results and the higher level of patent activity are significant only when control variables are excluded from the empirical model.

Ganguli, Kahn, and MacGarvie (2020) argue that one possible explanation for those results is that immigrants self-select from the right tail (high-skilled individuals) of the ability distribution. Furthermore, they argue that the right tail of the ability distribution is fatter than that of natives. This finding implies that immigrants have a larger percentage of individuals with STEM degrees or backgrounds. Hanson and Slaughter (2019) provide evidence that U.S. immigrants are overrepresented in STEM-related employment. This evidence is especially true for individuals with advanced degrees in STEM areas. For example, considering the workforce with PhDs, in 2013, foreign-born individuals between the ages of 25 and 54 made up 28.9 percent of hours worked by this elite population and 54.5 percent of STEM hours worked.

In a recent study, Burchardi et al. (2020) examined the impact of immigration on both innovation and economic dynamism for U.S. counties from 1975 to 2010. They stress that it is difficult to disentangle the causal relationship between immigration flows and innovation or economic performance. Does increased immigration improve the economy or does a strong economy attract immigrants? In this situation, researchers try to find variables that predict immigration flows but are not correlated with current economic conditions in the economy. For example, they might use the share of an economy’s population that are immigrants in the past to predict current immigration flows. So long as past immigration is not tied to current economic conditions, the estimated impact is unbiased in large samples. If past immigration is influenced by an unobserved factor that also impacts current economic conditions, then past immigration will not provide estimates with desirable statistical properties.4

In an effort to establish a causal relationship between immigration and innovation or economic dynamism, Burchardi et al. (2020) developed a model where immigration choices are influenced by economic and social factors. The model was used to calculated the amount of immigration caused by each factor. The non-European social factors component, which is independent of unobserved factors that also influence innovation and economic dynamism, was then used to predict immigration flows during the 1975–2010 period.

Burchardi et al. found immigration flows have a positive causal impact on U.S. county-level firm innovation and on economic dynamism. They found that a one standard deviation increase in migrants (approximately 12,000 migrants) increases the flow of patents to local firms in the county by 27 percent relative to the average patent flow. They also found more immigration increases economic dynamism or creative destruction. Once again, a one standard deviation increase in immigrants increases both job creation and destruction by 7 percent and 11 percent, respectively, relative to the average. It also increases real wages by about 3 percent relative to the average wage in a county. The authors also found that there are geographic spillovers to other counties, but they decline fairly quickly. The impact is also larger from immigrants with more education. This research shows immigration can have a significant impact on innovation and the performance of regional economies.

Finally, studies using firm data from the United Kingdom (Ottaviano, Peri, and Wright 2018) and France (Mitaritonna, Orefice, and Peri 2017) found that, where there are more immigrants, there are more productivity increases, which suggests greater innovation and improvements in efficiency occur within the affected firms.

The research presented in this section indicates that immigrants tend to be innovative. This result is attributed to a large percentage of immigrants with STEM degrees. The share of U.S. patents going to immigrants has significantly increased over time. Immigrant inventors are a complement to native inventors, thus raising their productivity over time.

Conclusion

In summarizing the current research about immigration, entrepreneurship, and innovation, this article provides evidence that immigration—especially among high-skilled entrepreneurial immigrants—increases innovation, firm startups, and general economic dynamism. The share of U.S. patents going to foreign-born individuals is growing significantly. Higher levels of skilled immigrants increase patents in the United States. High-skilled immigrants make native innovators more productive. These findings tell us that immigrants are playing a growing and important role in the production of new ideas, which is the principal engine of growth in the United States, thereby raising the standard of living of all citizens.

Expanding immigration would be a desirable policy reform. Family-based visas do not have the same effect on innovation and entrepreneurship as do skill- and employment-based visas. This fact does not imply that, as a country, we should stop issuing family reunification visas. The same is true with respect to refugees. The visa policies for such groups are created for humanitarian reasons. However, the United States should consider expanding the number of visas issued to foreign-born entrepreneurs and to individuals with STEM degrees. At a minimum, the country can set the H‑1B visa quota at a level that more closely matches demand (Griswold 2020; Palagashvili and O’Connor 2021).

References

Akcigit, U., and Kerr, W. R. (2018) “Growth through Heterogeneous Innovations.” Journal of Political Economy 126 (4): 1374–443.

Azoulay, P.; Jones, B. F.; Kim, J. D.; and Miranda, J. (2020) “Immigration and Entrepreneurship in the United States.” NBER Working Paper No. 27778.

Bernstein, S.; Diamond, R.; McQuade, T.; and Pousada, B. (2019) “The Contribution of High-Skilled Immigrants to Innovation in the United States.” Stanford University Business School Working Paper.

Bloom, N.; Jones, C. I.; Reenen, J. V.; and Webb, M. (2020) “Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?” American Economic Review 110 (4): 1104–44.

Brown, J. D.; Earle, J. S.; Kim, M. J.; and Lee, K. M. (2020) “Immigrant Entrepreneurs and Innovation in the U.S. High-Tech Sector.” In I. Ganguli, S. Kahn, and M. MacGarvie (eds.), The Roles of Immigrants and Foreign Students in U.S. Science, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship, 149–71. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Burchardi, K. B.; Chaney, T.; Hassan, T. A., Tarquinio, L.; and Terry, S. J. (2020) “Immigration, Innovation, and Growth.” NBER Working Paper No. 27075.

CBS News (2020) “Americans Weigh in on Issues before the Supreme Court: CBS News Poll.” Available https://drive.google.com/file/d/1BIG9z6d4OdhprnhaqQN0xbrwE14NPI3/view (June 8).

Congressional Budget Office (2020) Federal Responses to Declining Entrepreneurship. Washington: CBO.

Decker, R.; Haltiwanger, J.; Jarmin, R.; and Javier M. (2014) “The Role of Entrepreneurship in U.S. Job Creation and Economic Dynamism.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 28 (3): 3–24.

Fairlie, R. W. (2013) “Entrepreneurship, Economic Conditions, and the Great Recession.” Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 22 (2): 207–31.

Fairlie, R. W., and Desai, S. (2020) “2019 Early-Stage Entrepreneurship in the United States.” Kansas City: Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.

Fairlie, R. W.; Miranda, J.; and Zolas, N. (2018) “Job Creation and Survival among Entrepreneurs: Evidence from the Universe of U.S. Startups.” University of California, Santa Cruz, Working Paper.

__________ (2019) “Measuring Job Creation, Growth, and Survival among the Universe of Start-ups in the United States Using a Combined Start-up Panel Data Set.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 72 (5): 1262–77.

Gallup (2020) “Immigration.” Available at https://news.gallup.com/poll/1660/immigration.aspx.

Ganguli, I.; Kahn, S.; and MacGarvie, M. (2020) “Introduction.” In I. Ganguli, S. Kahn, and M. MacGarvie (eds.), The Roles of Immigrants and Foreign Students in U.S. Science, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship, 1–14. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Griswold, D. (2020) “Coming to America: Finally Fixing Legal Immigration.” Discourse (November 10): 1–12.

Hanson, G. H., and Slaughter, M. J. (2019) “High-Skilled Immigration and the Rise of STEM Occupations in U.S Employment.” In C. R. Hulten and V. A. Ramey (eds.), Education, Skills, and Technological Change: Implications for Future U.S. GDP Growth. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hunt, J. (2011) “Which Immigrants Are Most Innovative and Entrepreneurial?” Journal of Labor Economics 29 (3): 417–57.

Hunt, J., and Gauthier-Loiselle, M. (2010) “How Much Does Immigration Boost Innovation?” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2 (2): 31–56.

Jones, C. I. (1995) “R & D–Based Models of Economic Growth.” Journal of Political Economy 103 (4): 759–84.

__________ (2002) “Sources of U.S. Economic Growth in a World of Ideas.” American Economic Review 92 (1): 220–39.

__________ (2016) “The Facts of Economic Growth.” In J. Taylor and M. Woodford (eds.), Handbook of Macroeconomics. Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V.

__________ (2020) “The End of Economic Growth? Unintended Consequences of a Declining Population.” NBER Working Paper No. 26651.

Kerr, W. R. (2008) “The Ethnic Composition of U.S. Inventors.” Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 08–006.

__________ (2019) The Gift of Global Talent: How Migration Shapes Business, Economy and Society. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford Business Books.

Kerr, S. P., and Kerr, W. R. (2020) “Immigrant Entrepreneurship in America: Evidence from the Survey of Business Owners, 2007 and 2012.” Research Policy. 49 (3): 1–18.

Khanna, G., and Lee, M. (2018) “High-Skill Immigration, Innovation, and Creative Destruction.” NBER Working Paper No. 24824.

Krol, R. (forthcoming) “Immigration and American Labor Market Outcomes.” Arlington, Va.: Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Working Paper.

Liang, J.; Wang, H.; and Lazear, E. P. (2018) “Demographics and Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Political Economy 126 (51): S140–S196.

Lincicome, S. (2020) “The COVID Vaccines Are a Triumph of Globalization.” Cato Institute Commentary (December 8).

McCloskey, D. N. (2016) Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mitaritonna, C.; Orefice, G.; and Peri, G. (2017) “Immigrants and Firms’ Productivity: Evidence from France.” European Economic Review 96: 62–82.

Nowrasteh, A., and Powell, B. (2021) Wretched Refuse? The Political Economy of Immigration and Institutions. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ortega, F., and Peri, G. (2014) “Openness and Income: The Roles of Trade and Immigration.” Journal of International Economics 92 (2): 231–51.

Ottaviano, G. I., and Peri, G. (2006) “The Economic Value of Cultural Diversity: Evidence from U.S. Cities.” Journal of Economic Geography 6 (1): 9–44.

Ottaviano, G.; Peri, G.; and Wright, G. C. (2018) “Immigration, Trade, and Productivity in Services.” Journal of International Economics 112: 88–108.

Palagashvili, L., and O’Connor, P. (2021) “Unintended Consequences of Restrictions on H‑1B Visas.” Arlington, Va.: Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Policy Brief.

Peri, G. (2012) “The Effect of Immigration on Productivity: Evidence from U.S. States.” Review of Economics and Statistics 94 (1): 348–58.

Peri, G.; Shih, K.; and Sparber, C. (2015) “STEM Workers, H‑1B Visas, and Productivity in U.S. Cities.” Journal of Labor Economics 33 (S1, Part 2): S225–S255.

Romer, P. A. (1990) “Endogenous Technological Change.” Journal of Political Economy 98 (2): S71–S102.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010) Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.