In the hope that it would “#GetCoinMoving,” the U.S. Mint followed its strategic rationing program with a request for spare change. Both press releases and a social media campaign were used to promote the idea of paying with exact change, depositing coins at local banks, and exchanging coins at kiosks (Crawford 2020; U.S. Mint 2020b, 2020c; U.S. Treasury 2020).

In the private sector response, three general trends emerged throughout the country. Some businesses paid premiums for coins, others used digital payments alternatives, and others chose to discourage coin use entirely.

Once they recognized that a shortage had taken hold, many banks began paying premiums for coins in order to get hold of them. One bank launched a coin buyback program in which it offered a $5 bonus for every $100 worth of coins deposited or exchanged for paper money (Elassar 2020). Another bank offered a chance to win a $250 prize, and some banks waived fees for the use of coin-counting machines (Janey 2020).

Yet, some businesses chose to use nonmonetary incentives. Chick-fil‑A offered a free sandwich to anyone who exchanged $5 worth of coins for $5 worth of paper money (Lexington Chamber and Visitors Center 2020). Similarly, 7–11 gave away free drinks (Crawford 2020) and casinos even gave away free slot machine plays to anyone who brought in coins to exchange for paper money (Colonial Downs and Rosies Gaming 2020; Treasure Island 2020).

Though some businesses circumvented the shortage entirely by changing the way they accepted payments, others could not. Rather than incur the cost of continuing to use coins, they invested in alternatives. For example, laundromats began using mobile apps to activate their machines (Vanselow 2020), while other businesses began giving “digital change” through loyalty cards and gift cards (Abril 2020; Chen 2020). A few businesses even went so far as to create a system for customers to scan items and check out virtually (Goulding 2020b).

But not all businesses could afford to pay premiums or change their operations on such short notice. Some instead chose to either ration coins or discourage their use entirely. According to Fadia Patterson (2020), to prevent coins from “walking away,” one laundromat went so far as to hire attendants and install cameras to ensure that the coin machines were used only by customers. Further, Megan Vanselow (2020) reported that other businesses charged “convenience fees” on making change. And then some businesses—in an effort to put a positive spin on the perceived loss incurred by those unfamiliar with Swedish rounding16—turned the issue into an opportunity to raise donations for charity (Janey 2020). However, in the end, the most common approach was a sign that appeared at businesses across the country: “ATTENTION CUSTOMERS: The U.S. is currently experiencing a coin shortage. Please use correct change or other form of tender if possible. We apologize for any inconvenience this may cause.”17

Evidently, the federal government and private sector had very different approaches to the Covid-19 coin shortage. Although the federal government recognized that the issue at hand was one of coin distribution, its most substantial move was to increase coin production. In contrast, by offering premiums, changing operations, and discouraging coin use, the private sector used a more tailored approach.

Businesses recognized that one of the central issues was that people stopped using coins due to potential health risks. By paying a premium for coins, businesses mitigated the cost of that risk. People who were less concerned about the dangers were able to effectively profit from the jar of coins sitting in their laundry room. Similarly, for the businesses that could not afford to pay a premium to keep doing business with coins, it became clear that digital alternatives offered a new path forward. And, finally, those who could not afford either option moved swiftly to inform the public that they could no longer operate with coins or must do so on a limited basis.

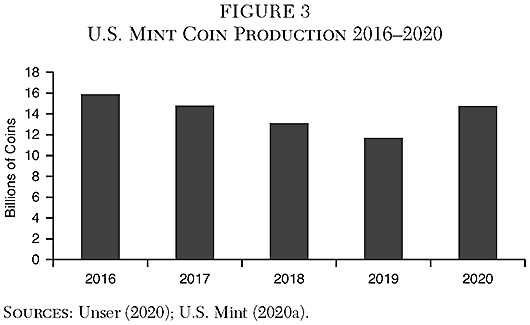

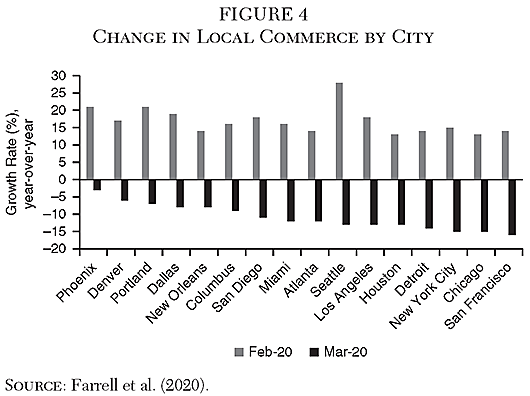

Covid-19 altered almost every facet of the human experience in 2020. However, the coin shortage was not the first coin shortage, and it is unlikely to be the last.18 So what lessons can we draw from it? First, novel crises require novel responses. The federal government’s response failed in this respect. Although coin rationing was rightly based on historical order volume and the U.S. Mint’s production levels, there is no sign that the regional effects of Covid-19 and shelter-in-place orders were taken into account (Federal Reserve Board 2020a).

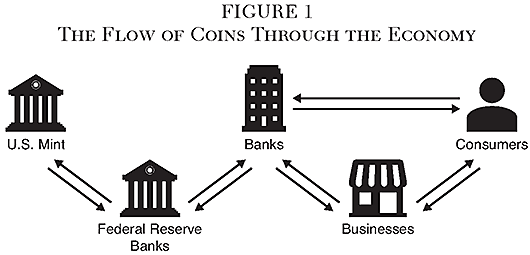

Second, the government does not act alone in the physical distribution of money. On paper, the government is in charge of money. However, in practice, consumers, businesses, and banks all have a role to play alongside the U.S. Mint and Federal Reserve. Their roles were evident both in the disruption to the circulation of coins and the private sector’s response. Greater cooperation between the public and private sectors could have created not only a swifter response but also a more tailored one.

The third, and last, lesson lies in what did not happen. Although history is rife with examples of the private sector stepping in to provide alternative money when official currencies have been in short supply (e.g., Selgin 2008; Champ 2007), that didn’t happen here. Why not? The most likely answer is that the U.S. government is not one to tolerate competition. In fact, it has said as much. While investigating the NORFED Liberty Dollar, the U.S. Mint (2006) issued a press release that stated:

NORFED’s “Liberty Dollar” medallions are specifically marketed to be used as current money in order to limit reliance on, and to compete with the circulating coinage of the United States. Consequently, prosecutors with the United States Department of Justice have concluded that the use of NORFED’s “Liberty Dollar” medallions violates 18 U.S.C. § 486, and is a crime.

As George Selgin (2009) previously said in response to Argentina’s coin shortage in 2009, the solution could be as simple as sanctioning private coins on the condition that acceptance is not mandatory and some minimum capital requirements back the coins. Such a sanction would welcome back the innovations that occurred during past coin shortages and solve the crisis in a way that keeps coins flowing for users who have no alternative.

Whether or not the Covid-19 coin shortage is taken as a learning experience is still to be seen. The private sector has certainly proven itself capable of serving a more active role in the distribution of money. Yet, if nothing else, the Covid-19 coin shortage has been a firm reminder of why it is important not to take the existence of coins for granted. For what might be a nuisance in your pocket one day may just disappear the next.

Abril, D. (2020) “Why Is There a Coin Shortage in the U.S.?” Fortune (July 18).

Anthony, N. (2020) “COVID’s Latest Trick: Making Coins Disappear.” Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) (July 20).

Centers for Disease Control (2020) “What Grocery and Food Retail Workers Need to Know About COVID-19.” Atlanta, Ga.: CDC (April 13).

Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB) (2019) “What Types of Fees Do Prepaid Cards Typically Charge?” Consumer Education (April 1).

Champ, B. (2007) “Private Money in Our Past, Present, and Future.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary (January 1).

Chen, N. (2020) “Coin Shortage Impacts Businesses across the U.S.” 9&10 News (July 10).

Colonial Downs and Rosies Gaming (2020) Twitter post (August 13): https://twitter.com/ColonialRosies/status/1293964325611360256.

Crawford, L. (2020) “Pandemic Causes Coin Shortage across the Country.” News12 Long Island (July 27).

Elassar, A. (2020) “A Bank Is Paying People to Bring in Their Spare Change to Help Local Businesses amid the Coin Shortage.” CNN (July 19).

Farrell, D.; Wheat, C.; Ward, M.; and Relihan, L. (2020) “The Early Impact of COVID-19 on Local Commerce.” New York: JPMorgan Chase.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) (2018) “FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households.” 2017 FDIC Survey. Washington: FDIC.

__________ (2020) “How America Banks: Household Use of Banking and Financial Services.” 2019 FDIC Survey. Washington: FDIC.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York (1999) “Shortage of Pennies and Other Coins.” Circular No. 11182 (September 1).

Federal Reserve Board (2020a) “Strategic Allocation of Coin Inventories.” FRB Services (June 11).

__________ (2020b) “Federal Reserve Convenes U.S. Coin Task Force with Industry Partners.” FRB Services (June 30).

__________ (2020c) “U.S. Coin Task Force Initial Report and Recommendations.” FRB Services (July 31).

Gladstein, A. (2021) Twitter post (May 21): https://twitter.com/gladstein/status/1395835550548983808.

Goulding, G. (2020a) “Less Coins Trickling through Area Banks, Businesses.” WTOV9 Fox (July 7).

__________ (2020b) “End Could Be in Sight for Coin Shortage as Businesses Continue to Adapt.” WTOV9 Fox (July 27).

Janey, J. (2020) “Coin Shortage Has Some Breaking Open Their Piggy Banks.” Winchestar Star (July 28).

Klein, A. (2020) Twitter post (March 10): https://twitter.com/Aarondklein/status/1237500733030875144.

Lexington Chamber and Visitors Center (2020) Twitter post (August 11): https://twitter.com/lexingtonsccoc/status/1293198960128139265?s=20.

MacArthur, R. (2020) “Coin Shortage Is a Real Issue.” Cape Gazette (August 21).

Masunaga, S. (2020) “Free Drinks, Store Credit and Cries for Help: How We’re Handling the Coin Shortage.” Los Angeles Times (July 30).

Mervosh, S.; Lu, D.; and Swales, V. (2020) “See Which States and Cities Have Told Residents to Stay at Home.” New York Times (April 20).

National Institutes of Health (2020) “New Coronavirus Stable for Hours on Surfaces.” NIH News Release (March 17). Available at www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/new-coronavirus-stable-hours-surfaces.

Papa John’s (2020) “No Contact Delivery from Papa John’s.” Available at www.papajohns.com/no-contact-delivery.

Patterson, F. (2020) “How WNY Laundromats Are Managing to Avoid the Coin Shortage.” Spectrum News (July 27).

Pietsch, B. (2020) “Cash Could Be Spreading the Coronavirus, Warns the World Health Organization.” Business Insider (March 5).

Prior, J. (2021) “Coin Shortage Eases As U.S. Ramps Up Production.” American Banker (January 10).

Selgin, G. (2008) Good Money: Birmingham Button Makers, the Royal Mint, and the Beginnings of Modern Coinage, 1775−1821. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

__________ (2009) “Argentina is Short of Cash–Literally.” Wall Street Journal (January 5).

Sell, S. (2020) “Coin Shortage Hits Retailers, Laundromats, Tooth Fairy.” Associated Press (August 18).

Semuels, A. (2020) “Many Companies Won’t Survive the Pandemic. Amazon Will Emerge Stronger Than Ever.” Time (July 28).

Siegel, R. (2020a) “Hang on to Your Nickels and Dimes, the Pandemic Has Created a Coin Shortage.” Washington Post (June 17).

__________ (2020b) “A Penny Pinch: How America Feel into a Great Coin Shortage.” Washington Post (September 1).

Smialek, J., and Rappeport, A. (2020) “A Penny for Your Thoughts Could Be a Lot Harder to Find.” New York Times (June 25).

Smith, K. A. (2020) “Is There Really a Coin Shortage?” Forbes (July 20).

Sumagaysay, L. (2020) “The Pandemic Has More Than Doubled Food-Delivery Apps’ Business. Now What?” MarketWatch (November 25).

Tobin, M. (2020) “Coin Shortages Are Causing a Liquidity Crisis at Laundromats.” Bloomberg Businessweek (August 1).

Treasure Island (2020) Twitter post (August 16): https://twitter.com/ticasino/status/1295043908381089792?s=20.

Unser, M. (2019) “U.S. Mint Produces 11.9 Billion Coins for Circulation in 2019.” CoinNews (January 31).

__________ (2020) “U.S. Mint Produces 14.77 Billion Coins for Circulation in 2020.” CoinNews (January 22).

U.S. Coin Task Force (2021) “#GetCoinMoving.” Available at https://getcoinmoving.org.

U.S. Mint (2006) “Liberty Dollars Not Legal Tender, United States Mint Warns Consumers.” Press Release (September 14).

__________ (2020a) “Circulating Coins Production.” Available at www.usmint.gov/about/production-sales-figures/circulating-coins-production.

__________ (2020b) Twitter post (August 27): https://twitter.com/usmint/status/1299041998742134786?s=20.

__________ (2020c) “U.S. Mint Public Service Announcement.” Available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=pWbGMmlniCw&ab_channel=USMINT.

U.S. Treasury (2010) “Production and Circulation.” Available at www.treasury.gov/resource-center/faqs/Coins/Pages/edu_faq_coins_production.aspx#.

__________ (2020) Twitter post (August 6): https://twitter.com/USTreasury/status/1291406310207033350.

Vanselow, M. (2020) “Got Some Spare Change? Maybe Not as Coin Shortage Grows.” KWTX (July 27).

Visa (2021) “The Visa Back to Business Study.” 2021 Outlook. Available at https://usa.visa.com/dam/VCOM/blogs/visa-back-to-business-study-jan21.pdf.