Interest rates declined in the wake of the 2007–2009 global financial crisis. They remained low for most of the 2010s, only rising modestly toward the end of the decade. In some European countries, interest rates even became negative. While limited to a few countries initially, the likelihood of more central banks following suit is growing in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Not least, the Federal Reserve System is under pressure to adopt a negative federal funds rate (Bernanke 2020; Lilley and Rogoff 2020).

The push for negative rates invites the question: What are their consequences? We examine this question empirically by analyzing the case of Sweden, one of the first countries to experiment with a negative policy rate, and the first country to complete the experiment.1 We then discuss the implications of our results for larger economies.

The Swedish central bank, the Riksbank, first entered negative rate territory when its deposit rate for commercial banks became negative in 2009. The Riksbank became a pioneer with this one small step. However, its main policy rate, the repurchase (repo) rate, remained positive. This situation lasted for only a brief period. In 2010, the Riksbank moved away from the negative deposit rate due to a rapidly recovering economy.

The second move came in February 2015, when the Riksbank announced a repo rate of −0.10 percent. This rate was further reduced to −0.50 percent in 2016, a level maintained until January 2019, when the rate was raised to −0.25 percent. A further increase of 25 basis points followed in December that year, terminating the subzero regime after five years.

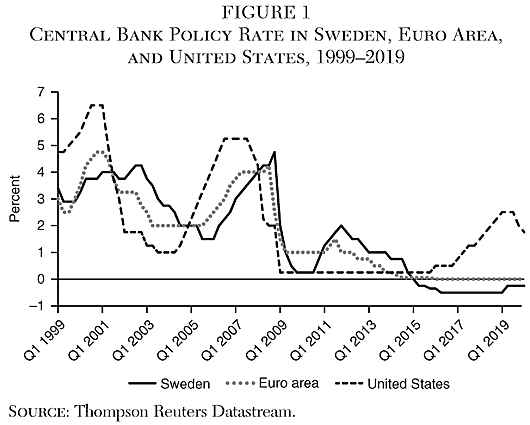

The move to a negative interest rate was an unusual step not only because the Riksbank became the first inflation-targeting central bank to break the zero lower bound, but also because the Riksbank broke its previous behavior of shadowing the European Central Bank (ECB). Figure 1 illustrates the policy rates in Sweden, the euro area, and the United States in the period between the introduction of the euro in 1999 to 2019. The Riksbank normally shadows the ECB’s policy rate. Here the 2015–2019 period stands out with the Riksbank being more expansionary compared to the two major central banks judging from the main policy rates.2

It is too early to make a full assessment of the long-run effects of the negative rates. However, we can already observe some of the short-run consequences. Thus, we focus on how negative rates affected the Swedish economy from 2015 to 2019. We discuss why the Riksbank took the drastic step of adopting negative rates, consider the short-run effects of this policy shift, and the lessons this episode offers for other countries.

Background of the Riksbank’s Negative Policy Rate

It is important to understand the background of the Riksbank’s experiment with negative policy rates. They were introduced not during a time of crisis, as in many other countries, but during a time of relative prosperity with high growth and record employment levels. They were the outcome of a long drift in the Riksbank’s approach to monetary policy. Over time, the Riksbank became increasingly dependent on a New Keynesian dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model, called Ramses. This model came to dominate the Riksbank’s thinking about the Swedish economy. As inflation fell below the official inflation target of 2 percent, despite a relatively strong economy, the model’s diagnosis was simple: high policy rates caused low inflation. Alternative explanations were discussed but largely disregarded in practice. The use of this specific model was a key driver behind the move toward negative rates. A broader analysis that emphasized, for example, financial stability would likely have resulted in a different policy.

Evolution of the Swedish Monetary Framework, 1993–2019

The Riksbank announced that it was adopting an inflation target in January 1993 following the collapse of the pegged exchange rate for the krona against the ECU during the European exchange rate crisis in the fall of 1992. The target was set at 2 percent within a tolerance band of plus or minus 1 percentage point. The Riksbank copied these numbers from the Bank of Canada’s framework.

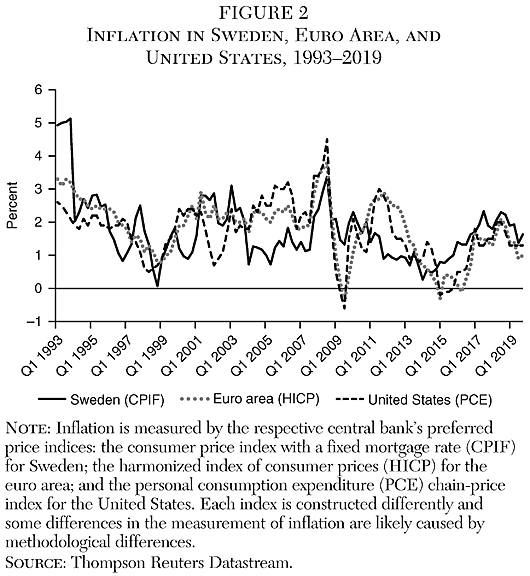

The initial reaction to the target was skeptical due to Sweden’s history of high inflation in the 1970s and 1980s. However, inflation fell and held steady at around 2 percent from the late 1990s until the early 2010s (Figure 2). From 1993 until 2019, inflation averaged 1.7 percent, which was well within the Riksbank’s original tolerance band of 1 to 3 percent3 (Andersson and Jonung 2017). As a comparison, the average inflation rate in the euro area was 1.8 percent during the same period, and average inflation in the United States was 1.7 percent. Not only are the averages similar, but as is evident from Figure 2, the comovements among the inflation series are high, suggesting that a large share of the variation in inflation was caused by global rather than national factors.4

The early years of the inflation target was a period of experiment for the Riksbank, as it had no recent experience of implementing inflation targeting. It had to develop its operational and communication strategies from scratch (Andersson and Jonung 2018). The framework that emerged toward the end of the 1990s was quite simple: the goal was to keep inflation close to 2 percent, within the band of +/−1 percentage point. The monetary policy strategy was forward-looking and described by the Riksbank as follows: “The basic rule for monetary policy is simple: if forecast inflation one to two years ahead is above/below 2 percent, the repo rate shall normally be raised/lowered in order to fulfil the inflation target. However, the rule is not applied mechanically and minor deviations from the target may be weighed against other factors” (Riksbank 2000:63).

In the early 2000s, the Riksbank became more reliant on formal economic modelling. Eventually in 2007, the Riksbank adopted a new operational strategy and a new communication strategy. A central component of the new strategy was forward guidance, in which the Riksbank began to publish forecasts of its own policy rate two to three years into the future (Andersson and Jonung 2019). The forecasts were produced using a combination of quantitative methods and qualitative discussions, with the DSGE model taking a major role in generating the quantitative forecasts and framing the qualitative discussion (Goodfriend and King 2015).5

The old simple rule-of-thumb approach that, if the inflation forecast was above the target, the Riksbank would increase interest rates, and vice versa, was abandoned. The new assumption imposed on the models was that “that the repo rate will develop in such a way that monetary policy can be regarded as well-balanced. In the normal case, a well-balanced monetary policy means that inflation is close to the inflation target two years ahead without there being excessive fluctuations in inflation and the real economy” (Riksbank 2007: 3). In other words, the Riksbank moved away from a more flexible approach where the forecast influenced the interest rate decision to one where the forecast itself played an important role as a policy instrument and in influencing the policy rate decision.6

Forward guidance and the forecasts of the Riksbank model soon dominated the discussion within the Board of Directors. The use of traditional economic indicators and qualitative judgements about the economy lost out. As Goodfriend and King (2015: 89) put it: “There is something surreal about the precision of the guidance provided by individual board members as to the future path of the repo rate when contrasted with the sheer uncertainty about the future and the fact that markets took rather little notice of the published path in determining their own expectations.”

Members of the Board spent much time arguing over whether the interest rate forecast several years into the future should be a few tenths of a percentage point higher or lower (Goodfriend and King 2015). The discussions rarely acknowledged that the forecasts were uncertain. Instead, several members apparently believed in monetary policy fine-tuning, where the smallest change in a forecast would have measurable effects on the macroeconomic outcome. In other words, the Riksbank became a hostage to its own model.

The shift toward the new strategy continued with the Riksbank abolishing the tolerance band in 2010. The new inflation target became “close to 2 percent” without further specification. The combined effect of forward guidance and of abolishing the tolerance band gave rise to a debate whether the Riksbank had fulfilled its target or not. Because average inflation was below 2 percent, but well within the original tolerance interval, critics argued that the Riksbank had voluntarily chosen to set aside the inflation target for some unexplained reason.

The Riksbank struggled to respond to these criticisms, because it had contributed to the view that it could fine-tune the economy by monetary policy and keep inflation exactly on the target. The new reliance on specific numerical forecasts, setting out a path into the future where the Riksbank always ended up meeting the target of 2 percent, helped to give the illusion of a high degree of control over future events by its policy.

The growing reliance on the Ramses model and on interest rate forecasts are key components in understanding the introduction of negative interest rates in Sweden. The DSGE model perspective dominated policy discussions within the Riksbank and shaped the decisions made by the Board of Directors. Alternative views were discussed but downplayed.

Introduction of Negative Interest Rates

The 2007–2009 global financial crisis had only a temporary effect on the Swedish economy. The financial system survived the crisis intact with the help of early emergency measures by the Riksbank. Nominal property prices continued to grow throughout the crisis while household debt levels stabilized at record levels. The real economy was hit by the Great Recession and the Swedish economy declined by roughly 5 percent in 2008 and 2009. The output loss was temporary and the economic recovery began in the second half of 2009. Real GDP had already surpassed its precrisis level by 2010. Inflation rose above the Riksbank’s official inflation target (Figure 2). Strong growth and higher inflation caused the Riksbank to begin to normalize its policy by gradually raising its policy rate to 2 percent in 2011. However, inflation began to decline following the euro crisis and the weakening of the euro area economy. By 2014, inflation was at only 0.5 percent.

As inflation fell, the Riksbank reduced its policy rate first to 0.75 percent in December 2013, and then to zero in 2014. Despite a falling policy rate, inflation did not pick up. The Riksbank faced growing blame from some economists and the media. Critics focused on the inflation number and ignored the relatively high growth rate of almost 3 percent and the high employment in 2014.

In response to these objections, the Riksbank announced the introduction of a negative policy rate and a program of quantitative easing in February 2015. The Riksbank claimed that a negative rate was needed to defend the credibility of the inflation target, thereby assuming responsibility for inflation falling short of the target and presuming that a negative rate would soon return inflation to the target. It expected its interest rate to be positive again before the end of 2016 (Riksbank 2015). These predictions proved wrong, and the Riksbank maintained its negative interest rate policy throughout the boom until December 2019, when it raised the interest rate to zero percent. However, the Riksbank chose to continue with its quantitative easing, totalling about 300 billion Swedish kronor by 2019, a sum close to 6 percent of GDP.

Effects of Negative Policy Rates

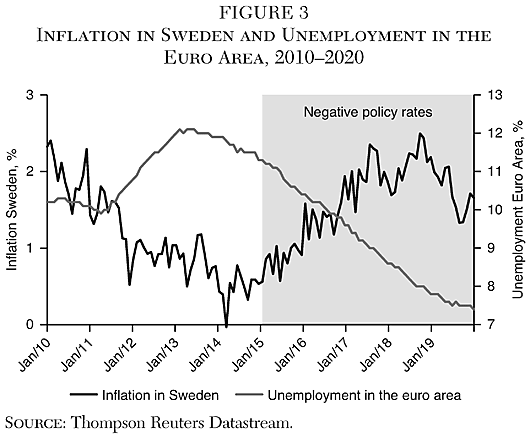

The aim of the negative policy rate was to raise domestic inflation. Inflation did indeed increase slightly after the introduction of negative rates, reaching the inflation target of 2 percent by 2018 before falling back to 1.5 percent in the second half of 2019. Based on this outcome, it is tempting to conclude that the policy of negative rates was at least partly successful in raising inflation. However, Swedish inflation is highly dependent on the state of the euro area economy. Swedish inflation falls when euro area unemployment increases, and vice versa (Figure 3). The correlation between the Swedish inflation rate and the euro area unemployment rate was −0.8 for the period 2009–2018. In contrast, the correlation between the Swedish inflation rate and the Swedish unemployment rate was lower, only −0.3 during the same period.

The Swedish economy is highly integrated with the European economy. Swedish exports as share of GDP increased from 30 percent during the 1980s (before Sweden’s membership of the European Union in 1995) to between 45 and 50 percent in the 2010s. About half of Swedish exports go to the euro area. Sectors that do not directly export to the euro area are still highly integrated with the euro area economy through their supply chains. Developments in the euro area thus directly affect the Swedish economy. As a result, improved economic conditions in the euro area are a more important factor behind the rise in inflation than the Riksbank’s policy based on negative rates.

The rise in inflation in Sweden was matched by a similar increase in inflation in the euro area, where inflation rose from −0.3 percent in February 2015 to 2 percent in the middle of 2018, and then fell to 1.4 percent in January 2020 (Figure 2). This is almost the same pattern as in Sweden, where inflation rose from 0.9 percent in February 2015 to 2 percent in the middle of 2018, and then fell to 1.2 percent in January 2020. That most of the movement in Swedish inflation correlates with changes in the euro area economy clearly indicates that the Riksbank’s influence over the Swedish inflation rate is modest due to the forces of a high level of economic integration. The Riksbank’s declining influence over the domestic inflation rate forced it to become increasingly extreme in its policy.

The situation was different when the inflation target was introduced in 1993. The Swedish economy was less integrated in the European economy and the Riksbank’s influence over the domestic inflation rate was much higher. In fact, Sweden had just experienced a 20 year period of relatively high and volatile inflation compared to its main trading partners. However, the influence has since gradually declined. Thus, the historically high correlation between the inflation rate and the state of the domestic economy has also declined.

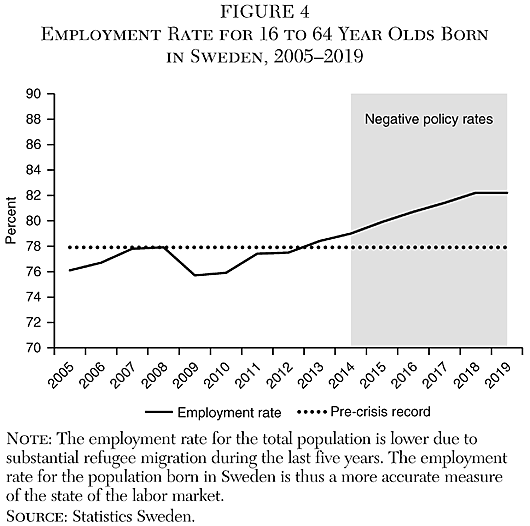

In the past, inflation increased during booms and declined during recessions. Today that correlation is much weaker. For example, in 2014 when inflation was low, pushing the Riksbank to introduce negative rates, the economy was booming. Growth was close to 3 percent and the employment rate for 16 to 64 year olds hit a record level, at close to 80 percent (Figure 4). The employment rate was even higher than during the precrisis boom of 2008. Instead of being countercyclical (tightening during booms), monetary policy became clearly procyclical. The Riksbank’s raising of rates in 2019 actually coincided with the economy moving toward a slowdown. The booming economy, without increasing inflation, is visible in the current account balance, which declined from steady surpluses of between 5 to 6 percent during 2008–2014 to a surplus of 1.7 percent in 2018. Rather than causing inflation, the boom contributed to rapidly rising imports.

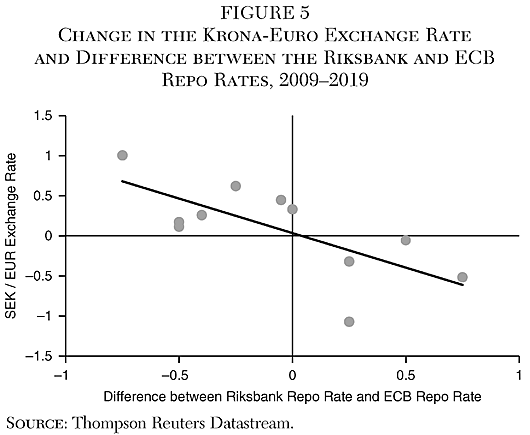

Reduced control over the domestic inflation rate does not imply that the Riksbank has no influence over the Swedish economy. There are still markets that are highly influenced by its policy. For example, Figure 5 illustrates the change in the krona-euro exchange rate in relation to the difference between the Riksbank’s repo rate and the ECB repo rate. Between 2015 and 2019, when the Riksbank maintained a lower policy rate than the ECB, the value of the Swedish krona declined from an average exchange rate of approximately 9.25 per euro between 1999 and 2012, to roughly 10.50 per euro. This corresponds to a depreciation of 12 percent. This weakening of the Swedish currency is one of the largest in modern times. Only the “super devaluation” of 16 percent in 1982, and the depreciation following the collapse of the pegged exchange rate in 1992 of about 20 percent, match the present persistent decline of the currency.

A depreciating currency should contribute to higher inflation. However, since the pass-through rate is low, the rise in consumer price inflation due to the depreciation is small. The overall increase in inflation between 2015 and 2019 from all factors affecting inflation was 1 percentage point. The exact effect of the exchange rate depreciation is difficult to gauge; however, it is unlikely to account for the entire increase in inflation. The contribution by the weakened exchange rate was less than a percentage point. Although the inflationary effect of the depreciation is small, the persistent weakening of the exchange rate may affect economic growth negatively in the future. Empirical evidence suggests that the many devaluations of the fixed exchange rates of the krona from the 1970s to the early 1990s reduced growth over the long term by lowering investments in new innovations by Swedish firms when they shifted from competing through quality and innovation to gaining market share through a weak exchange rate (see, e.g., Jonung 1991).

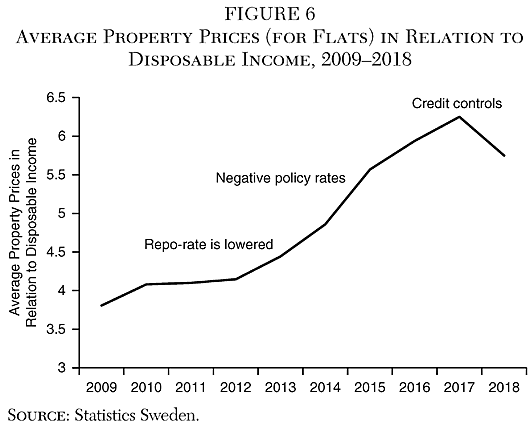

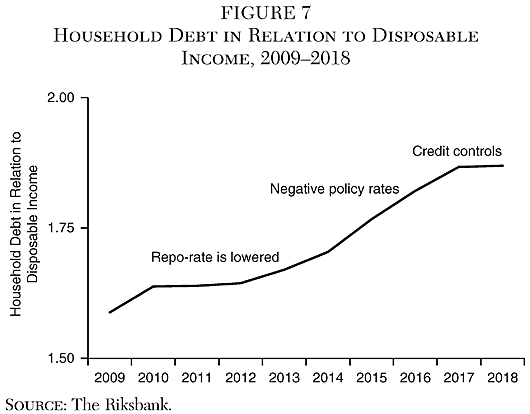

Another market that was highly affected by negative interest rates was real estate. Negative interest rates boosted property prices and household debt levels to new record levels relative to income. As in other countries, property prices increased rapidly prior to the global financial crisis of 2008, raising concerns of a future correction and possibly a financial crisis (Andersson and Jonung 2016). Nevertheless, Sweden suffered only briefly from the crisis of 2008 and avoided a full-scale banking crisis. House prices (Figure 6) and household debt levels (Figure 7) stabilized in 2010–2012 after the crisis. Temporarily higher interest rates during the economic recovery phase limited the rise in prices and debts. As the Riksbank softened its policy in 2012–2014 due to the euro area crisis, they slowly began to creep upward again.

Negative rates accelerated the speed of increase. Prices in relation to disposable income rose by 50 percent between 2012 and 2017, with most of the increase occurring after the introduction of negative rates in 2015. Rising prices and debt levels forced the financial supervisory authority (Finansinspektionen) to take action, imposing a string of credit controls on households, such as amortisation rules and debt ceilings, beginning in 2016. The controls dampened the rise in real estate prices and in debt, but also contributed to growing inequalities, because they mostly affected younger households and those without assets. Nonetheless, the credit controls did not arrest the upward trend in real estate prices. Prices increased from roughly four times disposable income in 2009 to six times in 2018. This compares to 1.5 times disposable income in the year 2000. In other words, property prices quadrupled in relation to disposable income between 2000 and 2018.

The average household debt ratio increased from 110 percent of disposable income to 187 percent during the same 20-year period. The Swedish pattern stands in contrast to the United States, where the household debt ratio was 105 percent of disposable income in 2018, having declined from a record 144 percent in 2007.

While the impact of negative rates on domestic inflation rate was small, probably negligible, the effects of negative rates on the housing market and on household debt levels were large. Imbalances that had already begun to emerge before the Great Recession worsened. Real estate prices rose rapidly, contributing to rising wealth inequality. Household debt reached record levels. The exchange rate of the Swedish krona depreciated by more than 10 percent, with no major impact on the domestic rate of inflation. In addition, monetary policy turned procyclical during the experiment with negative rates, contributing to record high employment. In short, the negative policy rates contributed to an economy suffering from “overheating”.

Was there an alternative policy? The Riksbank law permits the Riksbank to revise the inflation target as economic conditions change. The Riksbank is not required by law to maintain 2 percent inflation at any cost. There is no evidence of the Swedish economy suffering from low inflation. In fact, the economy performed quite well when inflation was below the target, growing by 2 to 3 percent per year and registering high employment figures.7

A policy that avoided negative interest rates would have implied lower consumer price inflation and a less overheated labour market, but would also have dampened the depreciation of the exchange rate and the rise of property prices. The risks of a future financial correction with potentially severe economic consequences would have been lower. Despite having the legal right to alter the inflation target, the Riksbank chose to experiment with the Swedish economy. In our view, it did so partially because of the narrow perspective that dominated the monetary policy discussion within the Riksbank. The negative interest rate experiment was a choice, not a necessity forced upon the Riksbank.

Lessons from Sweden

The Swedish experiment with negative interest rates offers several lessons. Due to globalization, the relationship between the state of the domestic economy and the consumer price inflation rate has been weakened (see, e.g., Auer et al. 2017). This is demonstrated by a large number of studies on the “flattening of the Phillips curve,” a phenomenon observed in many countries including the United States. However, central banks maintain a strong influence on the housing market and financial markets directly affected by the domestic interest rate, such as the foreign exchange market.

Rather than acknowledging their reduced influence over consumer price inflation, central banks have turned to increasingly extreme measures in their effort to raise this inflation rate, such as negative policy rates and quantitative easing. While quantitative easing and low policy rates started out as elements of a crisis policy during the international financial crisis, they have become common tools also during normal times of economic prosperity.

In Sweden, the gravitation toward extreme measures was connected with a growing dependence on an approach to monetary policy heavily influenced by a DSGE model based on a Phillips curve relationship to link the real economy to inflation, and a Taylor rule to model central bank behavior. The low inflation rate was interpreted as a crisis in itself, warranting a crisis policy response.

While the effect of an expansionary monetary policy on consumer price inflation is modest, imbalances tend to grow elsewhere in the economy. To address those imbalances, policymakers tend to rely on various forms of controls, including credit controls. These, in turn, distort the workings of markets. For example, they limit the effectiveness of monetary policy by restricting some of the channels through which monetary policy operates. The central bank ends up in a vicious cycle of overstimulating the economy while trying to control the negative side effects of the expansionary policy through various credit controls. The lessons from the past that credit controls distort markets and are commonly inefficient in achieving their aims are forgotten.

Are these lessons from the Swedish monetary experiment unique or are they valid also for a larger economy? The flattening of the Phillips curve and thus a reduction of central banks’ influence over the consumer inflation rate is a global phenomenon that has been observed for quite some time (see, e.g., Atkeson and Ohanian 2001; Blanchard 2016; Smets and Wouters 2007). Why the Phillips curve has flattened remains uncertain. A wide range of explanations have been suggested: digitalization, expectations, improved policy, wage stickiness, demographical change, structural change, and globalization, among others (see, e.g., Conti et al. 2017; Hooper et al. 2020; Kiley 2015). The specific reasons for the flattening are of less importance here; the fact that it is flatter is the key.

A negative interest rate in a large economy such as the United States would likely have a larger impact on consumer price inflation than a similar policy in Sweden. Still, the effect is likely to be relatively small. The effect on the U.S. housing market and financial markets are likely to be as large, if not larger, than in Sweden. The tradeoff between a small increase in consumer inflation versus larger financial imbalances is the same in the United States as in Sweden. A narrow focus on consumer inflation runs the risk of destabilizing asset markets when the central bank’s influence over the consumer inflation rate is waning. There is little international evidence for low inflation, or even moderate deflation, having a severe negative effect on the real economy. There is on the other hand ample evidence of financial imbalances causing severe economic damage not just in the short run but also in the long run. The negative effects of financial crises are often reenforced by growing political populism in the wake of the crisis (Eichengreen 2018).

Conclusion

Stefan Ingves, the governor of the Swedish Riksbank, described the use of negative interest rates as an “experiment” never tried before (Dagens Industri 2017). The experiment ended in 2019. We conclude at this early stage that the costs to Swedish society of negative interest rates most likely exceeded the benefits. Negative rates were the outcome of a narrow focus on consumer inflation and the flattening of the Phillips curve. To increase consumer inflation, the Riksbank felt forced to take extreme measures. Housing markets and financial markets responded quickly while consumer inflation remained largely unaffected.

There are clear lessons from the Swedish experience for the United States—despite differences in country size and the international role of the dollar and the Fed. Evidence from Sweden suggests that negative policy rates in the United States would lead to a rapid increase in housing prices, greater demand pressure, and a depreciating dollar, with only minor effects on consumer inflation rates. International evidence suggests that low inflation has no measurable negative effects on the economy. However, history shows that inflated asset prices carry the risk of a financial correction with potentially large negative economic and political consequences.

References

Adolfson, M,; Laséen, S; Lindé, J.; and Villani, M. (2007) “RAMSES—A New General Equilibrium Model for Monetary Policy Analysis.” Swedish Riksbank Economic Review 2: 5–40.

Atkeson, A., and Ohanian, L. E. (2001) “Are Phillips Curves Useful for Forecasting Inflation?” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 25: 2–11.

Andersson, F. N. G., and Jonung, L. (2016) “The Credit and Housing Boom in Sweden, 1995–2015: Forewarned is Forearmed.” VOXEU.org (May 30).

__________ (2017) “Inflation Targets and the Benefits of an Explicit Tolerance Band.” VOXEU.org (July 8).

__________ (2018) “Lessons for Iceland From the Monetary Policy of Sweden.” Lund University, Department of Economics Working Paper 2018:16.

__________ (2019) “The Tyranny of the Tenths. The Rise and Gradual Fall of Forward Guidance in Sweden 2007–2018.” Lund University, Department of Economics Working Paper 2019:14.

Auer, R.; Borio, C.; and Filardo, A. (2017) “The Globalization of Inflation: The Growing Importance of Global Value Chains.” BIS Working Paper No. 602.

Bernanke, B. (2020) “The New Tools of Monetary Policy.” American Economic Review 110 (4): 943–83.

Blanchard, O. (2016). “The United States Economy: Where to From Here?” American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 106 (5): 31–34.

Borio, C.; Erdem, M.; Filardo, A.; and Hofmann, B. (2015) “The Costs of Deflations: A Historical Perspective.” BIS Quarterly Review (March): 31–54.

Ciccarelli, M., and Mojon, B. (2010) “Global Inflation.” Review of Economics and Statistics 92 (3): 524–35.

Conti, A. M.; Neri, S.; and Nobili, A. (2017) “Low Inflation and Monetary Policy in the Euro Area.” ECB Working Paper No. 2005.

Dagens Industri (2017) “Stefan Ingves: Det är ett samhällsexperiment vi aldrig gjort tidigare” (It is an experiment with the national economy that we have never done before). Dagens Industri (November 14).

Eichengreen, B. (2018) The Populist Temptation: Economic Grievance and Political Reaction in the Modern Era. New York: Oxford University Press.

Eggertsson, G.; Juelsrud, R. E.; Summers, L. H.; and Wold, E. G. (2019) “Negative Nominal Interest Rates and the Bank Lending Channel.” NBER Working Paper No. 25416.

Goodfriend, M., and King, M. (2015) “Review of the Riksbank’s Monetary Policy 2010–2015.” Rapporter från Riksdagen 2015/16: RFR7.

Hooper, P.; Mishkin, F. S.; and Sufi, A. (2020) “Prospects for Inflation in a High Pressure Economy: Is the Phillips Curve Dead or is it just Hibernating?”, Research in Economics 74(1): 26–62.

Jonung, L. (ed.) (1991) Devalveringen 1982: Rivstart eller Snedtändning (The Devaluation of 1982: A Flying Start or a Bad Trip?). Stockholm: SNS Förlag.

Kiley, M. T. (2015) “Low Inflation in the United States: A Summary of Recent Research.” FEDS Notes, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Lilley, A., and Rogoff, K (2020) “The Case for Implementing Effective Negative Interest Rate Policy.” In J. Cochrane and J. Taylor (eds.), Strategies for Monetary Policy, Chap. 2. Stanford, Calif.: Hoover Institution Press.

Riksbank (2000) “Inflation Report 2000:1.” Stockholm: Swedish Riksbank.

__________ (2007) “Monetary Policy Report 2007:1.” Stockholm: Swedish Riksbank.

__________ (2015) “Monetary Policy Report 2015:1.” Stockholm: Swedish Riksbank.

Smets, F., and Wouters, R. (2007) “Shocks and Frictions in the U.S. Business Cycles: A Bayesian DSGE Approach.” American Economic Review 97: 586–606.

About the Authors

Fredrik N. G. Andersson is Associate Professor of Economics and Lars Jonung is Professor of Economics Emeritus at Lund University. They thank Michael Bergman, Per Frennberg, Kevin Dowd, Thorvaldur Gylfason, Jesper Hansson, Göran Hjelm, and Kurt Schuler for helpful comments on earlier versions of this article. The usual disclaimer holds.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.