Watching the frenzy surrounding Judy Shelton’s confirmation hearing before the Senate Banking Committee on February 13, one is led to believe that the gold standard is a “nutty” idea, for which no serious economist or monetary policymaker could possibly have a kind word (see U.S. Senate 2020). This article critiques that wholesale refutation of the gold standard. In recent years (as well as in the past), both serious economists and reputable monetary policymakers have recognized the benefits of a gold standard in reducing regime uncertainty and promoting monetary and social order. Whatever one may think of President Trump’s recent Fed picks, the gold standard itself deserves more respect than it’s been getting.

Misguided Criticisms

All serious persons agree that stable money of some sort is crucially important to social order. But journalists and others commenting on Judy Shelton’s views took for granted that a gold standard could not be consistent with such stability. Catherine Rampell (2020), a respected journalist with The Washington Post, wrote that “pegging the dollar to gold could restrict liquidity just when the economy needs it most, as happened during the Great Depression,” while Robert Kuttner (2020), another widely read journalist, opined:

As we painfully learned from economic history, a gold standard is profoundly deflationary, because it prevents necessary expansion of the money supply in line with economic growth. No serious person advocates it. . . . [I]f you want lower interest rates, the last thing you want is a gold standard.

Many economists have also argued against the gold standard. Lawrence H. White (2008, 2013, 2019b) has summarized their main arguments and concluded that they often set up straw men, misrepresent historical facts, and fail to understand that a genuine gold standard—as opposed to a pseudo gold standard—defines the unit of account as a given weight of gold, and gold serves as “the ultimate medium of redemption” (White 2013: 20). This is where a misunderstanding of the fundamentals occurs. According to White:

To describe a gold standard as fixing gold’s price in terms of a distinct good, domestic currency, is to begin with a confusion. A gold standard means that a standard mass of gold (so many troy ounces of 24-karat gold) defines the domestic currency unit. The currency unit (dollar) is nothing other than a unit of gold, not a separate good with a potentially fluctuating market price against gold. That $1, defined as so many ounces of gold, continues to be worth the specified amount of gold—or, in other words, that x units of gold continue to be worth x units of gold—does not involve the pegging of any relative price. Domestic currency notes (and checking-account balances) are denominated in and redeemable for gold, not priced in gold. They don’t have a price in gold any more than checking account balances in our current system, denominated in fiat dollars, have a price in fiat dollars [White 2013: 4; emphasis added; also see White 1999: 27].

The pre-1914 classical gold standard should not be confused with the interwar gold exchange standard, which was a pseudo gold standard. Treating them as a single system—called “the gold standard”—is highly misleading. The prewar regime (1879 to 1914) was a market-driven monetary system, in which the money supply responded to the demand for money and the dollar was convertible into gold. There was no U.S. central bank overseeing the system; the Federal Reserve System did not begin operation until 1914. In contrast, the interwar gold exchange standard was a managed regime under the direction of discretionary central bankers.

In comparing real versus pseudo gold standards, Milton Friedman (1961: 78) emphasized that a “pseudo gold standard violates fundamental liberal principles in two major respects. First, it involves price fixing by government. . . . Second, and no less important, it involves granting discretionary authority . . . to the central bankers or Treasury officials who must manage the pseudo gold standard. This means the rule of men instead of law” (Friedman 1961: 78). Although Friedman himself was not an advocate of the gold standard, he recognized its benefits in limiting the size of government and producing long-run price stability.

Unlike Friedman, David Wilcox, a former director of the Division of Research and Statistics at the Federal Reserve Board, does not distinguish between real and pseudo gold standards. He argues that the “gold standard” was “a disastrous experiment in monetary policymaking,” and that during the roughly 50 years since President Richard Nixon closed the gold window in August 1971, “central banks have learned how to control inflation with spectacular success.” Perhaps, but as White (2019b) has noted: “the inflation rate was only 0.1 percent over Britain’s 93 years on the classical gold standard, and “only 0.01 percent in the United States between gold resumption in 1879 and 1913.” He shows that, although the Fed has made progress since the Great Inflation of the 1970s and early 1980s, the longer-run record cannot match that of the real gold standard. The U.S. annualized inflation rate, under a pure fiat money regime, was 4.0 percent for the 50-year period from April 1969 to April 2019 (as measured by the urban consumer price index). Moreover, Wilcox fails to recognize that during the classical gold standard, there was no U.S. monetary policy as the term is commonly understood; there was no central bank!

While some highly respected authorities have good things to say about the classical gold standard, the interwar gold exchange standard has been universally condemned. Indeed, it was the breakdown of that standard—which depended much more heavily on cooperation among various central banks than its pre-1914 counterpart—that contributed to the Great Depression (see Bordo 1981; Eichengreen 1987; Friedman 1961; Irwin 2010; and Selgin 2013).1

Furthermore, not even the generally defective gold exchange standard can be blamed for having restricted liquidity in the United States’ case. So far as the U.S. was concerned, as Friedman states:

It was certainly not adherence to any kind of gold standard that caused the [Great Depression]. If anything, it was the lack of adherence that did. Had either we or France adhered to the gold standard, the money supply in the United States, France, and other countries on the gold standard would have increased substantially.2

Even a constitutional political economist like James Buchanan can point to the gold standard and see both its benefits and flaws. He writes: “I am not necessarily anti-gold standard. I think gold would be far better than what we have. But I think there might be better regimes” (Buchanan 1988: 45).

The gold standard is not a panacea. It is only one of many monetary arrangements that might succeed in checking arbitrary government. There are others. And all of them are imperfect. Because no arrangement is ideal, we must choose among realizable, imperfect alternatives—there are always tradeoffs. But it is also important to take a principled approach to thinking about monetary reform and not to simply accept the status quo.

Most economic historians accept that the “gold standard”—or, more accurately, the interwar “gold exchange standard”—contributed to the Great Depression. Yet the belief that the pre-1914 gold standard was responsible for the U.S. economic collapse of the early 1930s is a myth. It was the Federal Reserve’s policy mistakes, rather than its commitment to the gold standard, that was the major cause of the Great Depression. That, at least, is what Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz claim in their landmark book, A Monetary History of the United States.

The United States entered the 1930s with massive excess gold reserves. The Fed was not constrained in using those reserves to expand base money, and thus the broader money supply. As Richard Timberlake wrote in 2008:

By August 1931, Fed gold had reached $3.5 billion (from $3.1 billion in 1929), an amount that was 81 percent of outstanding Fed monetary obligations and more than double the reserves required by the Federal Reserve Act. Even in March 1933 at the nadir of the monetary contraction, Federal Reserve Banks had more than $1 billion of excess gold reserves. . . . Whether Fed Banks had excess gold reserves or not, all of the Fed Banks’ gold holdings were expendable in a crisis. The Federal Reserve Board had statutory authority to suspend all gold reserve requirements for Fed Banks for an indefinite period [Timberlake 2008: 309].3

More recently, both Timberlake and Thomas Humphrey, in their path-breaking book—Gold, The Real Bills Doctrine, and the Fed: Sources of Monetary Disorder, 1922–1938—identified the real culprit responsible for the Fed’s misconduct. Instead of adhering to the rules of the gold standard, Fed officials managed the Fed’s policies according to a fallacious theory known as the “Real Bills Doctrine.” That doctrine holds that the money supply can be regulated by making only short-term loans based on the output of goods and services. The problem is that adhering to that doctrine would link the nominal value of the money stock to the nominal expected value of real bills, and there would be no anchor for the price level.

Lloyd Mints had it right when he argued:

Whereas convertibility into a given physical amount of specie (or any other economic good) will limit the quantity of notes that can be issued, although not to any precise and foreseeable extent (and therefore not acceptably), the basing of notes on a given money’s worth of any form of wealth . . . presents the possibility of unlimited expansion of loans, provided only that the eligible goods are not unduly limited in aggregate value [Mints 1945: 30, emphasis in original].

Setting up straw men, misreading economic history, and using ad hominem arguments are no way to conduct a hearing or improve monetary policy. Richard Timberlake is correct in noting that unless policymakers understand the real causes of the Great Depression—namely, the failure of Fed policy to maintain a steady path for nominal GDP and the failure of the Real Bills Doctrine to guide monetary policy in an era that did not have a real gold standard—then they “are forever in danger of repeating past mistakes or inventing new ones” (Timberlake 2007: 326).

It is true that, during the classical gold standard, mild deflation did occur, but it was generated by robust economic growth and was beneficial, in contrast to the severe deflation that occurred during the Great Depression due to Fed mismanagement of the money supply.4

In their study of the link between deflation and depression for 17 countries over more than a century, Andrew Atkenson and Patrick J. Kehoe find:

The only episode in which there is evidence of a link between deflation and depression is the Great Depression (1929–1934). We find virtually no evidence of such a link in any other period. . . . [M]ost of the episodes in the data set that have deflation and no depression occurred under a gold standard [Atkenson and Kehoe 2004: 99, 101].

Moreover, under a commodity standard, long-run price stability allowed the British government to issue bonds without a maturity date, called “consols.” Interest rates on those securities were relatively low and actually fell, going from 3 percent in 1757 to 2.75 percent in 1888, and 2.5 percent in 1903. The United States issued consols during the classical gold standard, in the 1870s.5

What Policymakers Should Know About the Gold Standard

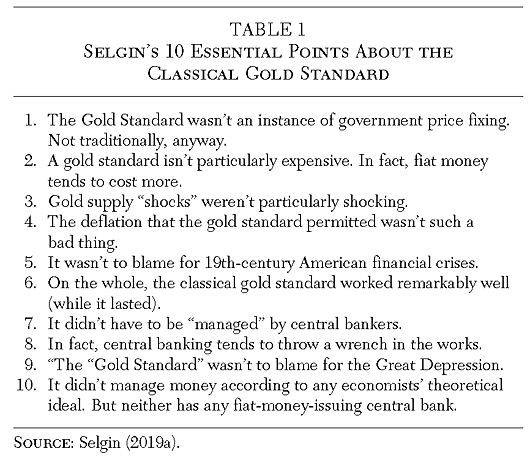

George Selgin (2015a) has provided a list of 10 things every economist and policymaker should know about the gold standard (Table 1). It is a response to various criticisms and fallacies that have persisted for some time, some of which have already been mentioned in the previous section. Without a keen understanding of each of the 10 points, which Selgin addresses in detail, confusion over the essence of a genuine gold standard (versus a pseudo gold standard) will lead to a dismissal of the key lesson of the classical gold standard—namely, its importance as a self-adjusting, spontaneous order and its consistency with limited government and freedom.

A rational discussion of the gold standard, as an alternative to a fiat money system, requires that journalists, economists, and policymakers become familiar with these 10 points and learn the details.6 A better understanding of the classical gold standard and the flaws of a pseudo gold standard would help inform monetary policy—even if there is little chance we could ever return to a true gold standard.

Importance of Thinking About Monetary Alternatives

There are many alternative monetary regimes, ranging from a pure commodity standard to a pure fiat money system. Serious debate over those alternatives is a worthwhile project, which Cato has been involved with for decades.7

The importance of studying the properties of alternative monetary regimes and their consequences for safeguarding an essential property right—namely, the promise of a monetary unit that maintains a stable purchasing power in both the short- and long-run—cannot be understated. Indeed, we should not forget that Article 1, Section 8, of the U.S. Constitution grants Congress “the power … to coin money, regulate the value thereof, and of foreign coin, and fix the standard of weights and measures.” That power was given to Congress, not to inflate the money supply, but to safeguard its value under a rule of law. Consequently, sympathy for gold can begin with a strict reading of that constitutional clause, the language of which clearly presupposes a commodity (gold or silver) standard. As Milton Friedman himself told members of Congress, “As I read the original Constitution, it intended to limit Congress to a commodity standard” (Friedman 2014: 652).

The “chief architect” of the Constitution, James Madison, was clear that his preference was for a commodity standard, not for a fiat money standard:

The only adequate guarantee for the uniform and stable value of a paper currency is its convertibility into specie—the least fluctuating and the only universal currency. I am sensible that a value equal to that of specie may be given to paper or any other medium, by making a limited amount necessary for necessary purposes; but what is to ensure the inflexible adherence of the Legislative Ensurers to their own principles and purposes? [Madison 1831; see Dorn 2018: 93].

Maybe such a concern is quaint, but it’s hardly nutty. In fact, it’s backed by a considerable base of knowledge on the history of money and monetary arrangements (see, e.g., White 2008).

Michael Bordo and Finn Kydland (1995: 424) highlight the gold standard’s ability to solve the time-inconsistency problem:

Our approach to gold-standard history posits that adherence to the fixed price of specie, which characterized all convertible metallic regimes including the gold standard, served as a credible commitment mechanism (or a rule) to monetary and fiscal policies that otherwise would be time inconsistent. On this basis, adherence to the specie standard rule enabled many countries to avoid the problems of high inflation and stagflation that troubled the late 20th century.

Furthermore, we argue that the gold standard that prevailed before 1914 was a contingent rule. Under the rule, gold convertibility could be suspended in the event of a well-understood, exogenously produced emergency, such as a war, on the understanding that after the emergency had safely passed convertibility would be restored at the original parity. Market agents would regard successful adherence as evidence of a credible commitment and would allow the authorities access to seigniorage and bond finance at favorable terms.

In sum, “When an emergency occurred, the abandonment of the [gold] standard would be viewed by all to be a temporary event since, from their [the public’s] experience, only gold or gold-backed claims truly served as money” (Bordo and Kydland 1995: 429).

Arthur J. Rolnick and Warren E. Weber, in their classic study “Money, Inflation, and Output under Fiat and Commodity Standards,” find that, “under fiat standards, rates of money growth, inflation, and output growth are all higher than they are under commodity standards” (Rolnick and Weber 1997: 1320). And Nobel Laureate economist James Buchanan, who favored a rules-based approach to monetary policy, argues:

The dollar has absolutely no basis in any commodity base, no convertibility. What we have now is a monetary authority [the Fed] that essentially has a monopoly on the issue of fiat money, with no guidelines that amount to anything; an authority that never would have been legislatively approved, that never would have been constitutionally approved, on any kind of rational calculus [Buchanan 1988: 33].

Like Buchanan, the constitutional political economist is interested in thinking about how to shape institutions to limit the power of government and allow free individuals to go about their own affairs. The pre-1914 gold standard provided “rules of the game,” in which human creativity flourished—and people could count not only on long-run price stability, but also on stable exchange rates. Finally, most authorities agree that the period from 1880 to 1914, when the classical gold standard prevailed, was one of innovation, wealth creation, free trade, and sound money. Joseph Schumpeter (1954: 405–6) emphasized:

An “automatic” gold currency is part and parcel of a laissez-faire and free trade economy. It links every nation’s money rates and price levels with the money-rates and price levels of all the other nations that are “on gold.” It is extremely sensitive to government expenditure and even to attitudes or policies that do not involve expenditure directly, for example, to foreign policy, to certain policies of taxation, and, in general, to precisely all those policies that violate the principles of [classical] liberalism.…It is both the badge and the guarantee of bourgeois freedom—of freedom not simply of the bourgeois interest, but of freedom in the bourgeois sense. From this standpoint a man may quite rationally fight for it.

Even John Maynard Keynes recognized the great benefits stemming from the pre-1914 gold standard:

What an extraordinary episode in the economic progress of man that age was which came to an end in August 1914! … The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as we might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep; he could at the same moment and by the same means adventure his wealth in the natural resources and new enterprises of any quarter of the world, and share, without exertion or even trouble, in their prospective fruits and advantages [Keynes 1020: 11].

It is a legitimate and important role of scholars to think about monetary alternatives—even when they may not appear politically feasible. This is one reason the Cato Institute established a Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives. It’s also why each year, our Annual Monetary Conference brings together the best minds to discuss, in a civil manner, how to improve current policies in order to increase trust in the future value of money and promote financial stability.8 From constitutional political economists to central bankers, we welcome contributions from across the spectrum in what we consider a crucial ongoing conversation.

What Would Gold Principles Bring to the Fed?

If one is unfit to serve on the Federal Reserve Board because he or she sees the beauty of the classical gold standard, then Alan Greenspan also should never have been allowed to serve on the Board. He too was a strong defender of the classical gold standard. In 1966, he wrote:

An almost hysterical antagonism toward the gold standard is one issue which unites statists of all persuasions. They seem to sense—perhaps more clearly and subtly than many consistent defenders of laissez-faire —that gold and economic freedom are inseparable, that the gold standard is an instrument of laissez-faire and that each implies and requires the other. In order to understand the source of their antagonism, it is necessary first to understand the specific role of gold in a free society [Greenspan 1966].

Although Greenspan lauded the classical gold standard, he realized that, once appointed, he would have to work within the existing legal framework—not advocate a return to the pre-1914 gold standard. Yet, his knowledge of how that system worked to maintain the value of money—and to allow interest rates, not central bankers, to allocate scarce capital—helped inform his approach to monetary policy at the Fed. Even many years after he began his long tenure as Fed chairman, Greenspan stated, in response to a question during his hearing before the House Committee on Financial Services on July 18, 2001: “Mr. Chairman, so long as you have fiat currency, which is a statutory issue, a central bank properly functioning will endeavor to, in many cases, replicate what a gold standard would itself generate” (Greenspan 2001: 34).

Conclusion

The operation of the classical gold standard offers many lessons for policymakers, including the importance of a credible commitment to a rules-based monetary regime and to enforceable private contracts under a just rule of law. This does not mean we should necessarily return to a gold standard, but simply that we should not dismiss that system as a “nutty idea.” The gold standard should be understood as one approach for attaining monetary stability. It is a rules-based system that brings about long-run price stability via market forces and the free flow of gold. It is also a monetary regime that is consistent with individual freedom and the rule of law. To be operational, common money (i.e., currency and checkable bank deposits) must be fully convertible into gold at the par value (i.e., as defined by the dollar as a given weight of gold). A central bank is unnecessary for the operation of a genuine gold standard.

Without a sound understanding of the 10 essential points about the classical gold standard, as expounded by Selgin (Table 1), journalists and others will continue to perceive the gold standard as a “nutty” idea .They will see central banking, under a discretionary fiat money regime, as the only viable alternative. That would be a huge mistake.

Learning from the past means recognizing the benefits—as well as the costs—of alternative monetary systems. Those who wish to improve the current system must offer new ideas that draw from the past, but also offer imaginative ideas for achieving monetary stability. Moving toward a rules-based monetary regime would, itself, be to honor lessons learned during the classical gold standard.

References

Atkeson, A., and Kehoe, P. J. (2004) “Deflation and Depression: Is There an Empirical Link?” American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings (May); 99–103.

Bordo, M. D. (1981) “The Classical Gold Standard: Lessons for Today.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 63 (May): 2–17.

Bordo, M. D., and Kydland, F. E. (1995) “The Gold Standard as a Rule: An Essay in Exploration.” Explorations in Economic History 32 (4): 423–64.

Bordo, M. D.; Lane, J. L.; and Redish, A. (2004) “Good versus Bad Deflation: Lessons from the Gold Standard Era.” NBER Working Paper No. 10329 (February).

Buchanan, J. M. (1988) “Prolegomena for a Strategy of Constitutional Reform.” In Prospects for a Monetary Constitution, special issue of the Economic Education Bulletin 28 (6): 7–15. Also see “Question and Answer Discussion Period”: 43–52.

Dorn, J. A., ed. (2017) Monetary Alternatives: Rethinking Government Fiat Money. Washington: Cato Institute.

__________ (2018) “Monetary Policy in an Uncertain World: The Case for Rules.” Cato Journal 38 (1): 81–108.

__________ (2019) “Jim Dorn on the History of Monetary Policy in Washington D.C. and its Future.” Interview with David Beckworth on Macro Musings. The Bridge, Mercatus Podcast (October 2).

__________ (2020) “The Classical Gold Standard Can Inform Monetary Policy.” Alt‑M (March 4).

Dorn, J. A., and Schwartz, A. J., eds. (1987) The Search for Stable Money: Essays on Monetary Reform. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Eichengreen, B. (1987) The Gold-Exchange Standard and the Great Depression.” NBER Working Paper No. 2198 (March).

Friedman, M. (1961) “Real and Pseudo Gold Standards.” Journal of Law and Economics 4 (October): 66–79.

__________ (2014) “Monetary Policy Structures.” Cato Journal 34 (3): 631–56.

Friedman, M., and Schwartz, A. J. (1963) A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Greenspan, A. (1966) “Gold and Economic Freedom.” The Objectivist; reprinted in A. Rand, Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal, chap. 6. New York; Signet, 1967.

__________ (2001) Testimony before the Committee on Financial Services, Including Responses to Questions, U.S. House of Representatives (July 18). In Conduct of Monetary Policy. Washington: Government Printing Office. Available at www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-107hhrg74156/pdf/CHRG-107hhrg74156.pdf.

Humphrey, T. M., and Timberlake, R. H. (2019) Gold, the Real Bills Doctrine, and the Fed: Sources of Monetary Disorder, 1922–1938. Washington: Cato Institute.

Irwin, D. A. (2010) Did France Cause the Great Depression?” NBER Working Paper No. 16350 (September).

Keynes, J. M. (1920) The Economic Consequences of the Peace. New York: Harcourt.

Kuttner, R. (2020) “Trump’s Latest Crackpot.” The American Prospect (February 10).

Madison, J. (1831) “[Letter] to Mr. Teachle” (Montpelier, March 15). In S. K. Padover (ed.), The Complete Madison: His Basic Writings, 292. New York: Harper and Bros., 1953.

Mints, L. (1945) A History of Banking Theory in Great Britain and the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rampell, C. (2020) “Yes, Trump’s Latest Fed Pick Is That Bad. Here’s Why.” Washington Post (February 10).

Rolnick, A. J., and Weber, W. E. (1997) “Money, Inflation, and Output under Fiat and Commodity Standards.” Journal of Political Economy 105 (6): 1308–21.

Schumpeter, J. (1954) History of Economic Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Selgin, G. (2013) “The Rise and Fall of the Gold Standard in the United States.” Cato Policy Analysis, No. 729 (June 20). Washington: Cato Institute.

__________ (2015a) “Ten Things Every Economist Should Know about the Gold Standard.” Alt‑M (June 4).

__________ (2015b) “A Rush to Judge Gold.” Alt‑M (August 12).

Timberlake, R. H. (2007) “Gold Standards and the Real Bills Doctrine in U.S. Monetary Policy.” The Independent Review 11 (3): 325–54.

__________ (2008) “The Federal Reserve’s Role in the Great Contraction and the Subprime Crisis.” Cato Journal 28 (2): 303–12.

U.S. Senate (2020) “Nomination Hearing” [for Judy Shelton and Cristopher Waller], Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs (February 13). Available at www.banking.senate.gov/hearings/02/03/2020/nomination-hearing.

White, L. H. (1999) The Theory of Monetary Institutions. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell.

__________ (2008) “Is the Gold Standard Still the Gold Standard among Monetary Systems? Cato Institute Briefing Paper No. 100 (February 8).

__________ (2013) “Recent Arguments against the Gold Standard.” Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 728 (June 20).

__________ (2019a) “A Gold Standard Does Not Require Interest-Rate Targeting.” Alt‑M (April 18).

__________ (2019b) “Fear of a Gold Planet.” Alt‑M (June 4).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.