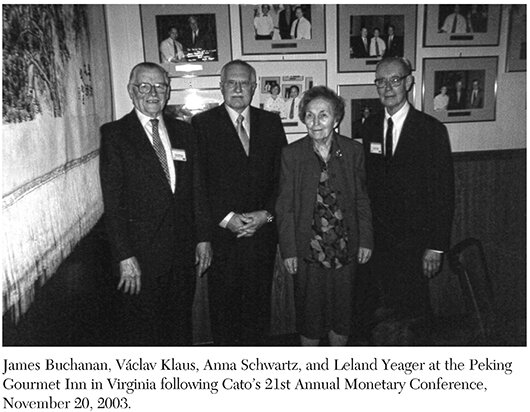

When Leland Yeager (1924–2018) passed away on April 23, at the age of 93, the world lost a brilliant mind, a devoted teacher, a dedicated scholar, and a man of integrity. I had the privilege of having Leland as a professor at the University of Virginia during my graduate studies in economics in the late 1960s, and later working closely with him as editor of the Cato Journal and director of Cato’s annual monetary conference. Of course, I didn’t need to edit his beautifully crafted papers and I studiously avoided sending his papers to a copyeditor! When he retired from the University of Virginia as the Paul Goodloe McIntire Professor of Economics, he left a legacy of excellence, as well as a host of stories about his legendary persona. All of his students know about “the yardstick” and “the stare.”1

In this memorial essay, I wish to paint a picture of Leland as a “market grandmaster,” in the sense of his keen understanding of markets and prices along with the role of money in facilitating exchange, and the importance of property rights in shaping incentives and behavior. Along with James Buchanan, Gordon Tullock, Ronald Coase, G. Warren Nutter, Roland McKean, and others, he was an important member of the Virginia School of Political Economy.

The Centrality of Market Exchange and Coordination

James Buchanan, who was instrumental in bringing Leland to the University of Virginia from the University of Maryland (Koppl 2006: 7), held that “economists should be ‘market economists’” — that is, “they should concentrate on market or exchange institutions . . . in the widest possible sense” (Buchanan [1964] 1979: 36). Buchanan also argued that the “most important social role [of economists] is that of teaching students,” and “the most important central principle in economics is . . . that of the spontaneous coordination which the market achieves” — namely, “the principle of spontaneous order” (Buchanan [1976] 1979: 81–82).

Leland excelled in the tasks that Buchanan thought most important. He was an outstanding teacher who placed market exchange and coordination at the center of his lectures. He wanted us to understand how the voluntary actions of individuals, guided by free-market prices and limited government, would lead to mutually beneficial exchanges and a harmonious market order in which people were free to choose. He also wanted us to recognize the significance of money in facilitating exchange and what happens when monetary disorder upsets the market system by distorting relative prices.

In the realm of public policy, he took a principled approach and sought to trace out the long-run effects of alternative policies, whether in the field of international trade or monetary policy. In his presidential address, “Economics and Principles,” at the 1975 meetings of the Southern Economic Association, he reiterated what his students knew well:

The principled approach to economic policy recognizes that the task of the policymaker is not to maximize social welfare, somehow conceived, and not to achieve specific patterns of outputs, prices, and incomes. It is concerned, instead, with a framework of institutions and rules within which people can effectively cooperate in pursuing their own diverse ends through decentralized coordination of their activities. In the macroeconomic field, it shuns activist “fine-tuning” and aims instead at a steady monetary framework [Yeager 1976a: 560].

Leland espoused “the principle of limited government” and argued that “even when no disadvantages are obvious, there is a presumption (defensible, to be sure) against a new or expanded government activity” (ibid., 562). He hoped that voters “might come to appreciate the value of avoiding myriad interventions and of orienting economic policies, instead, toward legal and monetary frameworks within which decentralized decisions are coordinated by market processes” — but he was not optimistic that voters “might come to judge policies and candidates in the light of the principle of limited government” (ibid., 565).

Yeager, nevertheless, saw it as his duty to “help explain the value of respecting principles not only in the realm of economic policy but also in other interactions among human beings” (ibid.). In thinking about “relevant strands of economic theory,” he pointed to the liberal concept of “results of human action but not of human design,” which F. A Hayek (1973: chap. 6) popularized, as well as

the importance, for a functioning society, of people’s having some basis for predicting each other’s actions; the inevitable imperfection, incompleteness, dispersion, and costliness of knowledge; the costs of making transactions and of negotiating, monitoring, and enforcing agreements, and the consequent usefulness of tacit agreements and informally enforced rules; applications of methodological individualism and of property-rights theory to analysis of nonmarket institutions and activities; concepts of externalities and collective goods and the supposed free-rider problem; and the principle of interdependence [Yeager 1976a: 565].

Like Buchanan, Leland was a fellow traveler of the Austrian School of Economics. Indeed, after he left the University of Virginia, he took a position at Auburn University as the Ludwig von Mises Distinguished Professor of Economics. Although he neither subscribed to the radical subjectivism of some Austrians nor fully accepted the Austrian theory of the business cycle, he noted the significance of thinking in terms of individuals, not aggregates; viewed competition as a market process; recognized the subjective nature of value; and understood the importance of sound monetary institutions and private property rights for maintaining a vibrant market system.

In his advanced price theory class, Yeager took time to review the socialist calculation debate and the absurdity of adhering to gross output targets, which would lead to the production of large nails that were useless. When he gave this example of the experience under Soviet central planning, Professor Yeager stopped in the middle of his lecture to leave the room because his face turned red with laughter at the absurdities that resulted from the lack of a real price system. However, he soon regained his composure and returned to carry on his lecture.

Throughout his career as a teacher and scholar, Leland always returned to fundamentals. In his keynote address at a meeting of the Chesapeake Association of Economic Educators, which I helped organize in 1979, he began by saying, “The economic ignorance that is so painfully evident in public-policy discussions is ignorance not of the subtleties of technicalities but of the basic truths. Economists should make an effort to communicate these basics, and not only to their students but also to a wider audience” (Yeager 1979).2 Moreover, “in our teaching we ought to point out not only truths but also ancient fallacies that keep being rediscovered in new guises with an air of triumphant novelty, e.g., [the] real-bills doctrine.”

Some of the basics Leland thought should be emphasized include:

Scarcity, rivalry among uses of resources, opportunity cost, the need for choice, choices made in the light of perceived costs and benefits (prices), the laws of supply and demand, specialization, decentralization, the general interdependence of economic activities, the coordination problem and the way that a market price-and-profit system handles it, the role of money in facilitating the operation of such a system (facilitating the fundamental exchanges of goods and services against goods and services), and the snarl that occurs when the quantity or growth rate of money changes erratically (here is the chief point of intersection between micro and macroeconomics [ibid.].

Finally, Yeager argued that, “in understanding how the economic system and the individuals that compose it behave, it is important to understand the opportunities open to individuals and the signals and incentives that impinge on them. This holds true not only of consumers, workers, and businessmen but also of people in government — politicians, economic regulators, and so forth.” He also warned, wisely, that:

Failure to appreciate the roles of prices and profits is tied up with failure to appreciate the problems of mobilizing knowledge, of coordinating decentralized activities, and of coping with obstacles to carrying out transactions. There is a tendency, perhaps found even more among high-powered theorists than among laymen, to regard the imaginary extreme case of pure and perfect competition as a standard for judging the real world. Relevant information is assumed to be automatically at hand; information and transactions costs tend to be forgotten. Hard facts of reality — including aspects of scarcity, the fact that resources have to be used in acquiring and transmitting knowledge and in conducting transactions — are seen as “imperfections” of our particular economic system. Reality is blamed for being real. Well, we should beware of planting any such misconceptions in the minds of our students [ibid.].

Because Leland was an authority on monetary economics and international monetary relations, as well as on alternatives to our present system of discretionary government fiat money, I now turn to those topics.

Money Is the Centerpiece of Macroeconomics

In his Chesapeake lecture, Leland called money “the centerpiece of macroeconomics.” He then went on to explain why. I will give a brief overview of some of Leland’s fundamental thoughts about the role of money in a market system.

Say’s Law Is Fundamentally Right

According to Yeager (1979), “There has been too much aggregation in macroeconomics, theoretical and applied — too much of the notion of aggregate demand confronting aggregate supply. Fundamentally, Say’s Law is right: supply of some goods and services constitutes demand for other goods and services; fundamentally there can be no problem of deficiency of aggregate demand.” However, “the exchange of goods and services against goods and services takes place through money.” When the supply of and demand for money do not mesh, monetary disequilibrium can upset the smooth operation of the market mechanism and Say’s Law must be qualified. This is especially true when price and resource adjustments are sluggish.

Consequently, Yeager emphasized that students need “to understand the tremendous importance of money in facilitating exchange and thus in facilitating the division of labor in producing the goods to be exchanged.” In particular, they need to recognize that “money facilitates economic calculation and the comparison of costs and benefits and the signaling function of price and profit” (ibid.).

Yeager goes on to argue that it is “precisely because money is so important to the working of the economic system [that] monetary disorders can have fateful consequences.” Thus, there is a “hitch in Say’s Law: Although ‘fundamentally’ goods and services exchange against goods and services, money is the intermediary in this process; and if the demand for and supply of money get out of balance, these fundamental exchanges are impeded” (ibid.).

Yeager elaborated on this idea elsewhere, explaining that an

imbalance between the actual quantity of money and the total of desired cash balances cannot readily be forestalled or corrected through adjustment of the price of money on the market for money because money, in contrast with all other things, does not have a single price and single market of its own. Monetary imbalance has to be corrected through the roundabout and sluggish process of adjusting the prices of a great many individual goods and services (and securities). Because prices do not immediately absorb the full impact of the supply and demand imbalances for individual goods and services that are the counterpart of an overall monetary imbalance, quantities traded and produced are affected also. Thus, the deflationary process associated with an excess demand for money, in particular, can be painful [Yeager 1983: 307].

It is to this theory of monetary disequilibrium that I now turn.

Monetary Disorder

Leland was influenced by the work of Clark Warburton and was put in charge of Warburton’s papers after his death. Those papers are now housed in the special collections at George Mason University.3 Like Warburton (1966), Yeager (1979) understood monetary disorder as “erratic disturbances to the relation between the actual quantity of money and the demand for money balances.” Those disturbances mean

not only wrong relative prices but also a wrong price level or purchasing power of the dollar, in relation to the quantity of money, [which] can snarl up exchanges. Anything that snarls up exchanges snarls up the production of goods to be exchanged, with cumulative consequences. Anything that undercuts the reliability of the dollar as a unit of account snarls up the accuracy of economic calculation, with fateful consequences [Yeager 1979].

This “theory of monetary disequilibrium” or “erratic money” has a long history that Warburton (1966: 1–35) resurrected (see Dorn 1987b: chap. 1). In his empirical studies after 1945, he emphasized “an erratic money supply as the chief originating factor in business recessions and not merely an intensifying force in the case of severe depressions” (Warburton 1966: 9). In May 1945, Warburton (ibid., 257) argued that “the theoretical developments since publication of Lord Keynes’s General Theory … have shifted attention away from the policies which produced the Great Depression and other cases of large departure from full employment, and have laboriously diverted the energies of economists into fruitless directions.”

Yeager followed Warburton’s lead and wrote an important article on “The Keynesian Diversion” (1973) and another on “The Significance of Monetary Disequilibrium” (1986), both of which are reprinted in The Fluttering Veil: Essays on Monetary Disequilibrium (Yeager 1997).

Money and Freedom: In Search of a Monetary Constitution

Leland was a member of the Mont Pelerin Society and a libertarian; he was a proponent of limited government and economic freedom, which he viewed as part of personal freedom. He was interested in examining a broad range of monetary alternatives to advance monetary theory and offer ideas for fundamental reform. In the fall of 1960, he organized an innovative conference for the Thomas Jefferson Center for Studies in Political Economy at the University of Virginia, which produced a book titled In Search of a Monetary Constitution, published by Harvard University Press in 1962.

That book has had a major influence in thinking about monetary reform from a constitutional perspective. In April 2012, to mark the book’s 50th anniversary, the Liberty Fund held a symposium in Freiburg-im-Breisgau, Germany, which was organized by Lawrence H. White, Viktor Vanberg, and Ekkehard Köhler — who acted as editors for Renewing the Search for a Monetary Constitution (2015). Leland, who could not attend the conference due to health issues, contributed a paper titled “The Continuing Search for a Monetary Constitution” (Yeager 2015).

By “constitution” Leland meant “rules of the game” in a broad sense — that is, both formal and informal rules that would lend predictability to human interactions and help bring about social and economic order. With respect to a monetary constitution, he was critical of the lack of a rules-based monetary policy and what he called “our preposterous dollar”:

On reflection, our existing monetary system [discretionary government fiat money] must seem preposterous. It is not difficult to understand how individually plausible steps over years and centuries have brought us to where we now are, but the cumulative result remains preposterous nevertheless. Our unit of account — our pervasively used measure of value, analogous to units of weight and length — is whatever value supply and demand fleetingly accord to the dollar of fiat money

If balance between demand for and supply of this fiat medium of exchange is not maintained by clever manipulation of its nominal quantity at a stable equilibrium value of the money unit, then any correction of this supply-and-demand imbalance must occur through growth or shrinkage of the unit itself. Money’s purchasing power — the general price level — must change. This change does not occur swiftly and smoothly. Money’s value must change, when it does, through a long-drawn-out, roundabout process involving millions of separately determined, though interdependent, prices and wage rates. Meanwhile, until the monetary disequilibrium has been finally corrected in this circuitous way, we suffer the pains of an excess demand for or excess supply of money [Yeager 1983: 305–6].

Leland argued that “some properties of actual monetary systems are illuminated by contrasting them with imaginary systems” (ibid., 305). He was interested in nongovernmental approaches to correcting deficiencies in the present monetary system. As he stated, “proposals for nongovernmental remedies intrigue me more” than “remedies within the realm of government money” (ibid., 308–9). In discussing “private money,” Yeager wrote:

As a libertarian, I favor allowing free banking — the competitive private issue of notes and deposits redeemable, presumably, in gold. Notes and deposits would be backed by merely fractional reserves, for efforts to enforce 100 percent banking in the face of contrary incentives and private ingenuity would require unacceptably extreme government interference [ibid., 318].

His preferred scheme, which was designed to eliminate or greatly reduce monetary disorder, was tentatively called the “BFH system,” after Fischer Black, Eugene Fama, and Robert Hall whose writings influenced Yeager and his coauthor Robert Greenfield (see Greenfield and Yeager 1983). Their proposed system is rather complex and is best summarized by Leland in his 1983 Cato Journal article:

Like the reform proposed by Hayek [1976, 1978], [the BFH system] would almost completely depoliticize money and banking. By the manner of [the state’s] withdrawal from its . . . domination of our current system, the government would give a noncoercive nudge in favor of the new system. It would help launch a stable unit of account free of the absurdity of being the supply-and-demand-determined value of the unit of the medium of exchange. The government would define the new unit, just as it defines units of weights and measures. The definition would run in terms of a bundle of commodities so comprehensive that the unit’s value would remain nearly stable against goods and services in general. The government would conduct its own accounting and transactions in the new unit. Thanks to this governmental nudge, the public-goods or who-goes-first problem of getting a new unit adopted would largely be sidestepped. The government would be barred from issuing money. Private enterprise, probably in the form of institutions combining the features of today’s banks, money-market mutual funds, and stock mutual funds, would offer convenient media of exchange. Separation of a unit of account of defined purchasing power from the medium — or rather media — of exchange, whose quantity would be appropriately determined largely on the demand side, would go far toward avoiding macroeconomic disorders and facilitating stable prosperity. Lacking any base money, whether gold or government-issued money, on which ordinary money would be pyramided on a fractional-reserve basis, the BFH system would not share the precariousness and vulnerability of ordinary monetary systems [Yeager 1983: 323–24].

The question inherent in the Yeager-Greenfield proposal is, Why would the government “give a noncoercive nudge in favor of the new system?”4 Perhaps Leland would think that question irrelevant, because his aim was to imagine a totally different type of system and to advance monetary theory — not to think that his idealized system would ever emerge, given the political economy/public-choice problems involved.

Leland did not believe the BFH system was the sole or best path to privatization; it was not intended to be “a definitive proposal.” Rather, it was to serve “as an example of one route to privatization” (Yeager 2015: 12). He offered four reasons for studying private alternatives to government money, even if they may not yet be politically feasible:

First, what is politically realistic can evolve. Second, although horrible to contemplate, a collapse of the government dollar would call for drastic reform. Third, keeping the government (or its agent, the Federal Reserve) from printing money will impose some discipline on its fiscal policies.… Fourth, considering how private money might work provides opportunities for progress in monetary theory [ibid., 9–10].

Yeager concludes by returning to a general theme, namely:

It is preposterous to try to remedy economic discoordination without even understanding coordinating processes in the first place and without understanding what obstacles and inhibitions sometimes impede productive transactions. Evident ignorance of economics, even at the highest levels of government, must itself sap the business and consumer confidence necessary for business recovery [ibid., 19].

Economics and Government

In his Chesapeake lecture, Yeager points to the importance of the economic way of thinking and methodological individualism in helping us recognize why government tends to overexpand:

The failure to appreciate the fact that decisions are made by individuals pursuing purposes of their own is perhaps worst when it comes to government.… The government, instead of being a philosopher-king, is a congeries of persons — politicians, legislators, bureaucrats, judges, and, once in a while, voters — all pursuing purposes of their own and operating with the fragmentary information that comes to their attention. Furthermore, nothing in government corresponds to the market process of spontaneous coordination of decentralized decisions. Nothing corresponds to the market’s way of bringing even remote considerations to the attention of each decentralized decision-maker in the form of prices. Knowledge, authority, incentives, and responsibility are largely fragmented and uncoordinated in the political and governmental process. Far-reaching and long-run consequences of government decision-making receive scant attention. There are reasons for thinking that these characteristics of government result in too much government — too much taxing and spending and regulation [Yeager 1979].

Leland goes on to argue that the free-market system allows for great diversity, which he deems a good thing. The voluntary nature of the market system provides for myriad opportunities for exchanges that reflect the diverse preferences of millions of traders. As he puts it, “A subjectivist and individualistic approach appreciates the diversity of people’s personalities and tastes and the attendant diversity of consumption and work patterns and of lifestyles generally. If we value the uniqueness of each human being, we are led to value a system that caters to diversity” (ibid.). He cautions, however that “recognizing the legitimacy of self-interest does not mean … approving of any and all self-interested behavior. It doesn’t justify lying, cheating, and stealing.”

Leland’s understanding of the free-market system made him a strong proponent of limited government and wary of government interventions under the guise of serving the “public interest.”

International Monetary Relations and the Necessity for Choice

In Yeager’s magnum opus, International Monetary Relations: Theory, History, and Policy,5 he notes: “It would seem odd that economists have not yet reached near-unanimity on the need, in framing international monetary policy, to sacrifice one or more individually desirable things. The necessity for choice is, after all, the most fundamental principle of economics” (Yeager 1976b: 651).

To illustrate the need for choice, Yeager (ibid.) turns to the “Doctrine of Alternative Stability,” which posits that among three desirable alternatives only two can be fully obtained. The three alternatives are (1) “freedom for each country to pursue an independent monetary and fiscal policy for full employment without inflation” (internal stability); (2) “freedom of international trade and investment from controls wielded to force equilibrium in balances of payments” (capital freedom/external balance without controls); and (3) “fixed exchange rates.” If a country chooses capital freedom (i.e., open capital markets), it “can maintain a fixed exchange rate only by sacrificing its monetary independence and allowing its domestic business conditions and price level to keep in step with foreign developments.”

Yeager goes on to say, “If countries do not openly choose which one to sacrifice among monetary independence, external balance without controls, and fixed exchanges, the choice gets made unintentionally.” For example, “in the early years after World War II — the ‘transition period’ of the IMF Charter — freedom from controls was sacrificed to national pursuit of full employment. Since then, the choice has become fuzzier as countries seek a compromise in the merely partial sacrifice of each of the three objectives” (ibid., 652).

China is a textbook case in this regard: policymakers have made the renminbi convertible for current account transactions and have been slowly opening the capital account, while making the exchange rate more flexible and using domestic monetary policy to spur the economy. If China is to establish a world-class capital market, it needs the free flow of capital, which means policymakers will have to choose either monetary independence under a floating rate system or a genuine fixed-rate system. Because China is a large player in the global trading system, it would make sense for Beijing to float the renminbi and remove capital controls, using domestic monetary policy to stabilize nominal GDP and maintain long-run price stability. However, in a political system dominated by the Chinese Communist Party, lacking both a genuine rule of law and a free market in ideas, there is little incentive to make the fundamental choice in favor of capital (and personal) freedom. That is why Eswar Prasad (2017) does not think the renminbi will become a “safe haven” currency for some time.

In sum, “historical evidence illustrates … the logically inexorable need to sacrifice one of the three objectives forthrightly or two or three of them in part” (Yeager 1976: 652).

Conclusion

Leland Yeager never lost sight of the logic of the market price system, the benefits of limited government and private property rights, the dignity of the individual, and the beauty of the market process and its spontaneous order. Like Buchanan, he understood that the order of the market emerges from the process of voluntary exchange, and that such a result depends crucially on the institutions supporting and framing a free-market system.6

One institution that is of the utmost importance is sound money — that is, money with a predictable and stable purchasing power. Yeager’s emphasis on how monetary disorder (monetary disequilibrium) can disrupt relative prices and their coordinating function, and make economic calculation more difficult, made him deeply interested in examining alternatives to discretionary government fiat money, including privatization. He was searching for a “monetary constitution” that would anchor expectations about the future value of money and thus help facilitate exchange — widening the scope of markets and thus the range of options open to individuals.

References

Breit, W.; Elzinga, K. G., and Willett, T. D. (1996) “The Yeager Mystique: The Polymath as Teacher, Scholar and Colleague.” Eastern Economic Journal 22 (2): 215–29.

Buchanan, J. M. ([1964] 1979) “What Should Economists Do?” In What Should Economists Do? chap. 1. Indianapolis: Liberty Press.

__________ ([1976] 1979) “General Implications of Subjectivism in Economics.” In What Should Economists Do? chap. 4. Indianapolis: Liberty Press.

__________ (1982) “Order Defined in the Process of Its Emergence.” Literature of Liberty 5 (4): 5. A note stimulated by reading Norman Barry, “The Tradition of Spontaneous Order,” Literature of Liberty 5 (4): 7–58.

Dorn, J. A. (1987a) “The Warburton Collection at George Mason.” History of Economics Society Bulletin 8 (Winter): 41–48.

__________ (1987b) “The Search for Stable Money: A Historical Perspective.” In J. A. Dorn and A. J. Schwartz (eds.) The Search for Stable Money, chap. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Greenfield, R. L., and Yeager, L. B. (1983) “A Laissez-Faire Approach to Monetary Stability.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 15 (August): 302–15.

Hayek, F. A. (1973) Rules and Order, vol. 1 of Law, Legislation and Liberty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

__________ (1976) Choice in Currency. Occasional Paper 48. London: Institute of Economic Affairs.

__________ (1978) Denationalisation of Money, Hobart Paper Special 70, 2nd ed. London: Institute of Economic Affairs.

Koppl, R. (2006) “A Zeal for Truth.” In R. Koppl (ed.) Money and Markets: Essays in Honor of Leland B. Yeager, chap. 1. New York: Routledge.

O’Driscoll Jr., G. P. (1983) “A Free-Market Money: Comment on Yeager.” Cato Journal 3 (1): 327–33.

Prasad, E. S. (2017) Gaining Currency: The Rise of the Renminbi. New York: Oxford University Press.

Warburton, C. (1966) Depression, Inflation, and Monetary Policy: Selected Papers, 1945–1953. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press.

White, L. H.; Vanberg, V. J.; and Köhler, E. A., eds. (2015) Renewing the Search for a Monetary Constitution: Reforming Government’s Role in the Monetary System. Washington: Cato Institute.

Yeager, L. B., ed. (1962) In Search of a Monetary Constitution. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Yeager, L. B. (1973) “The Keynesian Diversion.” Western Economic Journal 11 (June): 150–63.

__________ (1976a) “Economics and Principles.” Southern Economic Journal 42 (4): 559–71.

__________ (1976b) International Monetary Relations: Theory, History, and Policy, 2nd ed. New York: Harper and Row. (First edition printed in 1966.)

__________ (1979) Keynote Address at the meeting of the Chesapeake Association of Economic Educators, University of Baltimore, December 7; from Leland Yeager’s unpublished note cards.

__________ (1983) “Stable Money and Free-Market Currencies.” Cato Journal 3 (1): 305–26. Reprinted in J. A. Dorn and A. J. Schwartz (eds.) The Search for Stable Money, chap. 14. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

__________ (1986) “The Significance of Monetary Disequilibrium.” Cato Journal 6 (2): 369–95.

__________ (1997) The Fluttering Veil: Essays on Monetary Disequilibrium. Edited with an introduction by G. Selgin. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

__________ (2015) “The Continuing Search for a Monetary Constitution.” In White, Vanberg, and Köhler (2015: chap. 1).

1 See “The Yeager Mystique” by William Breit, Kenneth Elzinga, and Thomas Willett (1996). The first two authors were Leland’s colleagues at Virginia, and the third was a former student. Yeager often brought a yardstick to class to draw complex diagrams. He sometimes stood on a chair and extended the graph onto the cinder blocks to get it perfectly to scale. (I am the safe-keeper of “the yardstick,” which I received from Ed Olsen when I hosted a retirement party for Leland at Cato.) “The stare” refers to Yeager’s penchant for avoiding small talk and simply staring at you intensely until you made a fool of yourself and departed his office totally embarrassed. As one graduate student recalled, “From the moment you entered his office you knew you were in trouble. Your simple question like ‘Will you be offering International Trade in the fall?’ was met by this stunned look of disbelief and a penetrating look straight into your eyes” (ibid., 222). Yet, those who got to know Leland found that he was an engaging conversationalist, a considerate mentor, and an excellent dinner host who enjoyed fine wines and knew their provenance (ibid., 224–25).

2 Although his speech, which was given at the University of Baltimore on December 7, 1979, was never published, he prepared note cards that were neatly typed and, jointly, read like an article. The quotes are from those cards, which were preserved in my files.

3 For a summary of the Warburton collection, see Dorn (1987a).

4 Gerald P. O’Driscoll Jr. (1983) points to this and other problems with the BFH system.

5 This book first appeared in 1966; the second edition was published in 1976. Quotes in the text come from the 1976 edition.

6 According to Buchanan (1982), “The ‘order’ of the market emerges only from the process of voluntary exchange among the participating individuals. The ‘order’ is, itself, defined as the outcome of the process that generates it.”