Edward Lazear, Stanford economics professor and former chairman of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers, has said, “The entrepreneur is the single most important player in a modern economy” (Lazear 2002: 1; see also Holcombe 1998). The emphasis on entrepreneurship and small and startup businesses as key engines in job creation, innovation, and economic growth has a long history, going back to Adam Smith. Not surprisingly, governments around the world view promoting entrepreneurship as a national and local priority. The interest is driven primarily by evidence that small and young businesses create a disproportionate share of new jobs in the economy, represent an important source of innovation, increase national productivity, and alleviate poverty (Reynolds 2005, OECD 2005, U.S. Small Business Administration 2011, Decker et al. 2014).

A frequently held view, often supported by research, is that immigrants are especially entrepreneurial, a sentiment commonly shared by policymakers and reflected in immigration policies. Many developed countries, including the United States, have created special visas and entry requirements in an attempt to attract immigrant entrepreneurs (Fairlie and Lofstrom 2015). In addition to possible contributions to economic growth, employment, and innovation, immigrant business ownership may also act as a tool to enhance immigrant labor market integration and success (Cummings 1980). For example, self-employment may alleviate informational gaps regarding education, skills, and experience gained by immigrants in their home countries, where U.S. employers are uncertain about how foreign-obtained human capital relates to productivity in the United States. Labor market discrimination and limited English proficiency are other possibly relevant hurdles faced more by immigrants than by U.S.-born workers. Although relevant across all levels of skills, this arguably may be most relevant to low-skilled immigrants, who face the highest hurdles to hiring in an increasingly skill-intensive economy.

This article analyzes recent U.S. data to examine how immigrants during the last 15 years have contributed to entrepreneurship through self-employment and earnings. It aims to address the questions of how do immigrants contribute to recent U.S. self-employment trends, in what industries are immigrant entrepreneurs concentrated, and how do their earnings compare to those of U.S.-born entrepreneurs? Before turning to the analysis, aimed to provide a broader understanding of contributions of immigrants to entrepreneurship, I begin with a brief overview of the relevant literature.1

Literature Review of Immigrant Entrepreneurship

There are a number of relevant ways to measure entrepreneurship and immigrant contributions to it. One is by measuring business ownership and startups. A body of research has consistently found that business ownership is higher among the foreign-born than the native-born in many developed countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia (Borjas 1986; Lofstrom 2002; Clark and Drinkwater 2000, 2010; Schuetze and Antecol 2007; Fairlie et al. 2010). Immigrants in the United States are also found to be more likely to start businesses than the native born (Fairlie 2008).

Other measures of entrepreneurship also point toward significant immigrant contributions. For example, as a recent review of the relevant literature shows, immigrants are greatly over-represented among U.S.-based Nobel Prize winners, high-impact companies, patent applications, and members of the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Engineering (Fairlie and Lofstrom 2015). They are also over-represented among founders of high-tech companies, biotech firms, biotech companies undergoing initial public offerings, and public venture-backed U.S. companies. Nonetheless, some researchers urge caution about interpreting immigrant contributions to the high-tech sector of the economy. Hart and Acs (2011: 116) conclude that “most previous studies have overstated the role of immigrants in high-tech entrepreneurship.”

There is evidence of broader contributions by skilled immigrants to innovation. For example, Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle (2010) find that the increase in the share of the U.S. immigrant population with at least a college degree increased the country’s patents per capita by about 21 percent. Importantly, they point out that their analysis does not suggest that immigrants are innately more able than the native-born but that the higher rate of patenting among college graduate immigrants is entirely explained by the greater share of immigrants with science and engineering education compared to the native-born. Another influential study, by Kerr and Lincoln (2010), assesses the impact of high-skilled immigration on technology formation as measured by science and engineering employment and patenting. They find that high-skilled temporary workers from India and China on H-1B visas in the United States account for a significant share of the growth in U.S. immigrant science and engineering employment. A key takeaway is that the growth is accomplished without crowding out native-born scientists and engineers.

However, not all evidence points toward such positive and beneficial effects of immigrant entrepreneurship. Specifically, there is some evidence that immigrant entrepreneurs may crowd out native-born entrepreneurs (Fairlie and Meyer 2003). This limited evidence is mixed, and even within the same study, the findings also indicate that immigration increases earnings among the native-born self-employed. In light of the less than clear picture of the role of immigration on native business owners, Fairlie and Meyer (2003: 647) suggest that the results “may be due to immigrants primarily displacing marginal or low-income self-employed natives, but our analyses do not provide clear evidence supporting this hypothesis.”

The notion and relevance of self-employment as an economic stepping stone, as well as a tool in immigrants’ economic assimilation process in the host country, has been explored by a number of researchers. Most researchers have focused on examining whether business ownership tends to rise with time in the new country, and generally find a positive relationship (Borjas 1986, Clark and Drinkwater 2010, Lofstrom 2002, Schuetze 2009, and Andersson and Wadensjö 2005). Fewer studies have analyzed assimilation earnings patterns among immigrant self-employed business owners.

Lofstrom (2002) analyzes both self-employment probabilities and earnings and finds that both increase along with time spent in the United States. Specifically, he finds that self-employed immigrants are relatively successful and may even reach earnings parity with observationally similar U.S.-born entrepreneurs after about 25 years in the country. For wage-earning immigrants, however, he does not find evidence of earnings convergence relative to their native-born wage-earning counterparts. In an analysis that also includes immigrants in Canada and Australia, Antecol and Schuetze (2007) find that in all three countries self-employment increases with the time in the country but that in terms of earnings outcomes relative to natives, self-employed immigrants in the United States outperformed immigrants in those two countries. This finding is interesting and policy relevant because, unlike immigrants to Canada and Australia, U.S. immigrants are not extensively selected and admitted based on skills. This feature may be due to the self-selection of immigrant entrepreneurs, with the most promising foreign-born entrepreneurs favoring the United States because of potentially higher returns to their capital compared with countries with more equal income distributions.2

Recent Trends in Immigrant Entrepreneurship

To examine trends in immigrant self-employment, as well as success as measured by earnings, I use the 2000 U.S. Census and 2005–14 American Community Survey (ACS). I classify those individuals who report being self-employed in both unincorporated and incorporated businesses and working at least 15 hours per week.

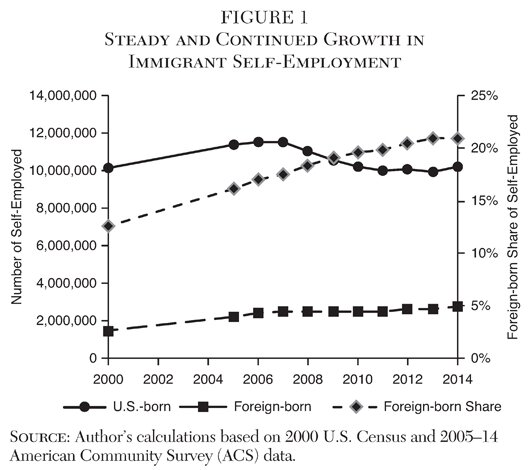

The data reveal some striking immigrant contribution to entrepreneurship. While the share of immigrants in the U.S. labor force has grown from about 12.5 percent in 2000 to 16.7 percent in 2014, as Figure 1 shows, immigrants’ share of the self-employed over the same period grew from 12.5 percent to 21 percent. In other words, about one in five self-employed workers in the United States are now foreign born.

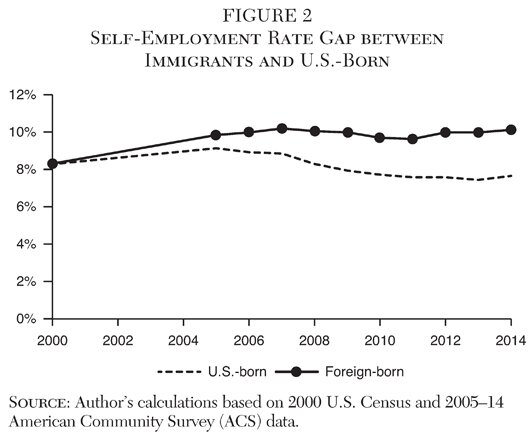

Although growth in the immigrant population partly accounts for the increase in the foreign-born share of self-employed, a divergence in the likelihood of choosing self-employment between immigrants and natives has also contributed to the trend. Figure 2 shows that in 2000, the self-employment rate among both U.S.-born and foreign-born workers was 8.3 percent. However, in subsequent years, the immigrant self-employment rate has been increasingly higher than the U.S.-born rate, and by 2014 the immigrant self-employment rate was 2.5 percentage points higher (7.6 percent and 10.1 percent respectively for U.S.- and foreign-born individuals).

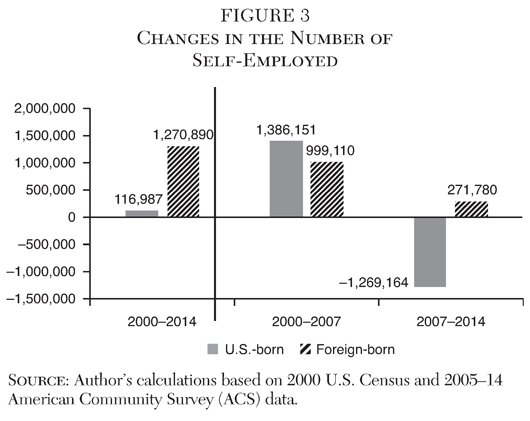

Arguably more striking is the immigrant contribution to the growth in the number of workers who report being self-employed. Between 2000 and 2014, the total number of self-employed in the United States grew by about 1.4 million, a growth of about 12 percent. Most noticeable is that immigrants accounted for about 1.3 million of the added number of self-employed individuals in the United States, as Figure 3 shows. In other words, more than 90 percent of the total growth in self-employment between 2000 and 2014 can be attributed to immigrants.

This change played out differently before and after the Great Recession. As Figure 3 also shows, between 2000 and 2007, U.S.-born self-employment grew by about 1.4 million, a growth of almost 14 percent. Immigrant self-employment increased over the same period by almost 1 million, or almost 70 percent. During this boom period, immigrants accounted for about 42 percent of the self-employment growth in the United States.

The data also show that immigrants have played an even more important role in self-employment growth since the Great Recession. While the absolute growth rate in immigrant self-employment decreased dramatically between 2007 and 2014, increasing by only about 272,000, this sharply contrasted to the dramatic drop in U.S.-born self-employment of 1.3 million. The data quite strongly suggest that immigrants contribute significantly to entrepreneurship, as measured by self-employment, in boom times but may play an even more important role during recessions.

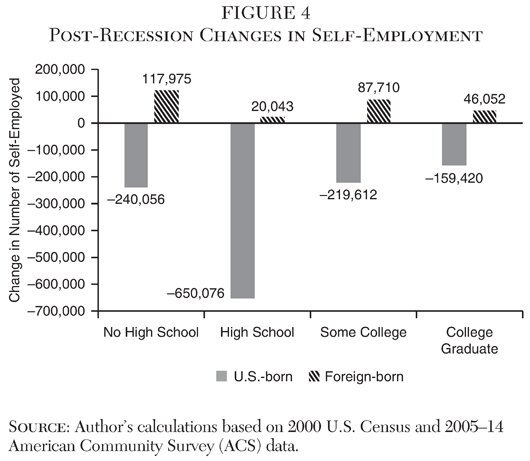

The post-recession increase in immigrant self-employment can be seen across skill groups, as measured by educational attainment, but as Figure 4 shows, immigrants with less than a high school diploma account for much of that growth—118,000 of the total increase of roughly 272,000. The data also show that the decline in self-employment among U.S.-born workers is across the board but slightly more than half the drop, about 650,000, was among those with a high school diploma. Roughly half the increase in immigrant self-employment, roughly 134,000, was among those with at least some college education.

The data show quite clearly that self-employment is an increasingly important labor market alternative for immigrants and therefore immigrants contribute increasingly to business ownership in the United States. The next section examines the industries where the contributions are concentrated.

What Are the Key Immigrant Self-Employment Industries?

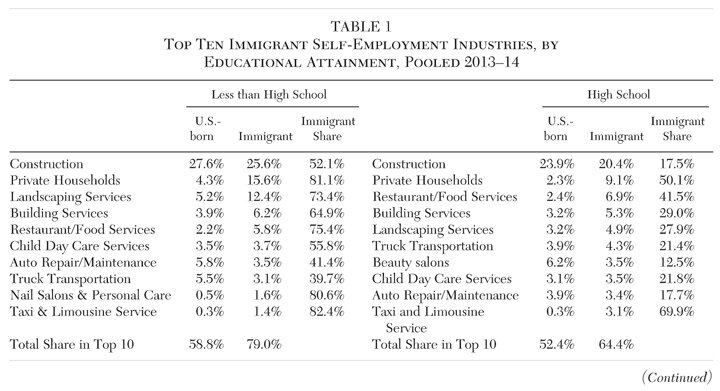

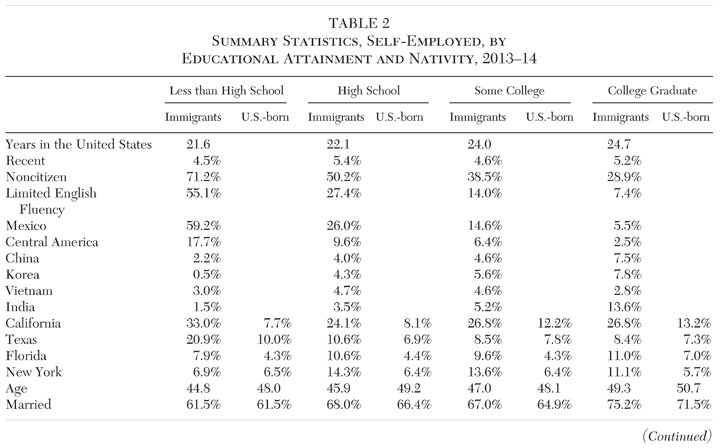

Since entry into self-employment and business ownership varies across skill groups, this section disaggregates the descriptive industry analysis by highest level of educational attainment—less than high school, high school credential, some college and college graduate. To do so, I use the four-digit industry variable available in the ACS to determine the share of self-employed individuals in each of the 256 industries and focus on the 10 industries, separately for each skill group, with the highest concentration of immigrant business owners. Furthermore, to get a more up-to-date snapshot, I focus on the most recent years in the ACS data, 2013–14.

Both immigrant and U.S.-born business owners with less than a high school diploma are highly concentrated in a relatively few industries. As Table 1 shows, about 79 percent of low-skilled self-employed immigrants are in the 10 industries where immigrants are most concentrated (close to 59 percent of low-skilled U.S.-born business owners are in these 10 industries). The most common self-employment industry for both U.S.- and foreign-born individuals lacking a high school credential is construction, at 27.6 percent and 25.6 percent, respectively. Among low-skilled immigrants, construction is followed by private household work (15.6 percent) and landscaping services (12.4 percent). In other words, slightly more than half of all low-skilled self-employed immigrants, 53.6 percent, can be found in just these three industries. More than one in three, or 37.1 percent, low-skilled natives own businesses in these three industries. Other common industries among immigrants in this skill group are in ser-vices, including building services, restaurants, and child care.

While less concentrated in relatively few industries, more than half of self-employed immigrants with a high school degree or some college own businesses in one of the skill group-defined top 10 immigrant industries, 64.4 percent and 50.4 percent respectively. Construction, private household, and restaurant industries are the three most common for both of these intermediate skill groups. In fact, the most common immigrant industries are identical, with the exception that landscaping is among the top 10 for high school graduates but not among immigrants with some college. Instead, real estate makes the list as the fourth most common industry for the latter group. Overall, the most common industries are not strikingly different between immigrants with no high school diploma and immigrants with a high school diploma or some college.

Table 1 also shows that high-skilled immigrants, defined as college graduates or higher, operate business in many noticeably different industries. The only overlap in the most common immigrant industries between immigrant college graduates and the other skill groups are in construction, real estate, and restaurants. Instead, health care (physicians and dentists), consulting (management, scientific, or technical), computer systems design, legal services, architectural and engineering, and accounting services make up the most common immigrant industries.

A look at the industrial composition of self-employed immigrants points to important contributions in a number of key industries. Not surprisingly, these include some industries often perceived to be immigrant industries. For example, regardless of educational attainment, immigrant businesses are more greatly concentrated in services like restaurants, child care, private household, and personal transportation (taxi and limousines) than are U.S.-born businesses. Especially striking, more than two thirds of all personal transportation businesses are immigrant-owned. Self-employed immigrants also contribute significantly to many high-skilled industries, especially health care and computer system design.

How Well Do Self-Employed Immigrants Do in the United States?

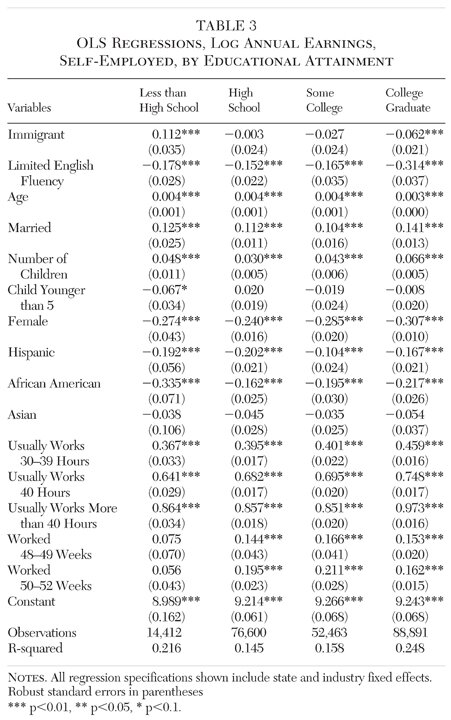

Earnings are another relevant measure of economic contributions and can be used as a gauge of how well self-employed immigrants do in the U.S. labor market, especially when compared to similar U.S.-born business owners. As such, comparisons of differences in earnings between self-employed immigrants and the native-born shed light on contributions, relative success, and labor market integration. To make such a comparison, I estimate separate earnings regressions, by skill group, while controlling for plausible earnings determinants such as age, level of English proficiency, gender, race/ethnicity, household composition, geographic location, and industry. I use the log of annual earnings as the dependent variable and include controls for weeks worked. To focus the analysis on those most actively engaged in self-employment, I exclude those who report working less than 40 weeks the previous year in their reported owned business.

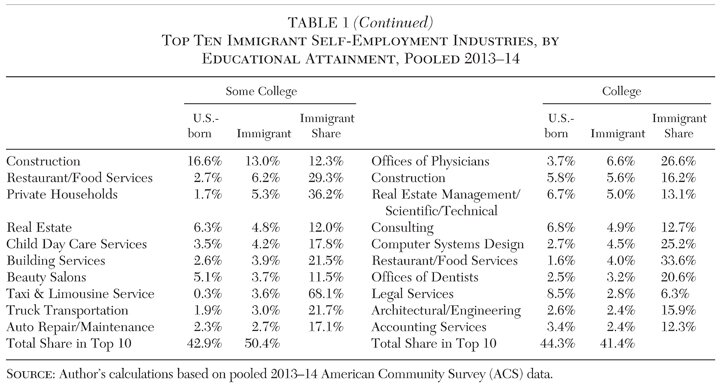

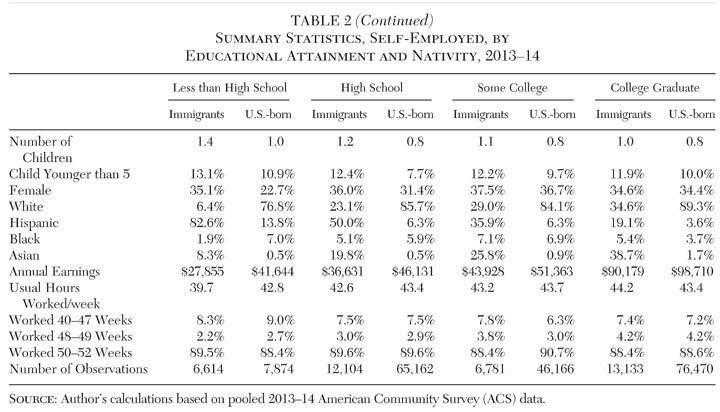

The summary statistics for the analytical samples are shown in Table 2. Some interesting observations include these:

• There is a high prevalence of limited English proficiency among both self-employed immigrants lacking a high school credential and those with no education beyond high school.

• The share of the self-employed who are Asian increases with educational attainment among both foreign- and U.S.-born, but is especially noticeable among immigrants.

• The vast majority of self-employed immigrants reside in just four states—California, Florida, New York, and Texas.

• A very small share of U.S.-born business owners are minorities.

• Only high-skilled immigrant business owners work more hours per week than U.S.-born entrepreneurs with the same level of educational attainment.

Finally, but very interestingly, Table 2 also shows that while on average, the U.S.-born self-employed business owners have higher annual earnings than do the self-employed immigrants, the gap decreases with educational attainment. As annual earnings increase more with educational attainment among self-employed immigrants than among their U.S.-born counterparts, the data also suggest that the returns to education among the self-employed are greater among immigrants than among the native born.

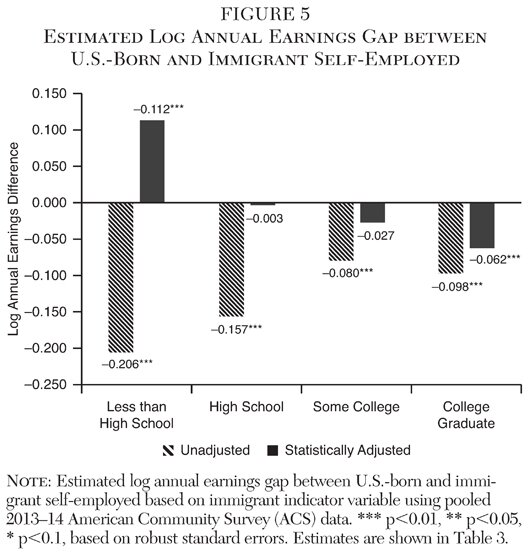

Of course, many factors may contribute to differences in earnings between self-employed immigrants and natives. For example, the fact that more than half of self-employed immigrants with no high school credential report limited English proficiency surely contributes to their relatively lower earnings. Conversely, the substantially greater concentration of low-skilled self-employed immigrants in relatively high-paying states like California and New York, all else equal, inflates the earnings of self-employed immigrants. For a better apples-to-apples comparison, I estimate earnings regressions accounting for observational differences between immigrant and native-born business owners. Although the earnings regression includes many interesting and informative estimates (shown in Table 3), I focus on the estimated log annual earnings gap between U.S.-born and immigrant self-employed—that is, the estimated immigrant indicator variable coefficient.

Figure 5 shows both unadjusted and adjusted earnings gaps between immigrant and native-born self-employed. The unadjusted gaps are statistically significant across all educational attainment groups. The largest gap is among the least-educated self-employed, where immigrants earn roughly 21 percent less on average than the low-skilled self-employed born in the U.S. The unadjusted difference is about 16 percent among high school graduates and less than 10 percent for those with some college or college graduates.

However, once we compare otherwise observationally similar immigrant and native self-employed individuals, there is no evidence of statistically significant lower earnings among self-employed immigrants, except among college graduates. In fact, the estimates suggest higher immigrant earnings among the least-educated self-employed. However, among college graduates a statistically significant immigrant-native gap of about 6 percent remains even after all controls are included. In additional model specifications where indicator variables for years in the United States were added, the gap is reduced with time spent in the United States. Annual earnings are not statistically significantly lower for high-skilled immigrants who have been in the United States for at least 15 years.3

Overall, the earnings results indicate that self-employed immigrants mostly have annual earnings as high as the U.S.-born self-employed, controlling for relevant factors such as demographic characteristics, skill levels, geographic location, and industry.

Conclusion

A broad body of research shows that entrepreneurs and small and young businesses are key engines of job creation, innovation, and economic growth. Not surprisingly, governments around the world view promoting entrepreneurship as a national and local priority. A frequently held view, often supported by research, is that immigrants are especially entrepreneurial, a sentiment commonly shared by policymakers and reflected in immigration policies. Many developed countries have created special visas and entry requirements in an attempt to attract immigrant entrepreneurs (Fairlie and Lofstrom 2015).

In the United States, immigrants increasingly contribute to entrepreneurship. Those contributions may be especially significant during economic downturns. While the share of immigrants in the U.S. labor force has grown from about 12.5 percent in 2000 to 16.7 percent in 2014, immigrants’ share of the self-employed over the same period grew from 12.5 percent to 21 percent. Immigrants account for more than 90 percent of the growth in self-employment since 2000, with particularly significant contributions since the Great Recession. Between 2000 and 2007, U.S.-born self-employment grew by about 1.39 million, a growth of almost 14 percent. Immigrant self-employment increased over the same period by almost 1 million, or almost 70 percent. During this boom period, immigrants accounted for about 42 percent of the self-employment growth in the United States. While there was a loss of almost 1.3 million U.S.-born self-employed since 2007, immigrants added about 272,000. There were increases across all education groups but growth in low-skilled immigrant self-employment is especially notable.

Self-employed immigrants in the United States are found in a wide range of industries, but they play especially important roles in a number of relatively low-skilled service industries and important high-skilled sectors such as health care and computer design. For example, more than two-thirds of the self-employed who report owning a business in personal transportation are immigrants. Immigrants, regardless of educational attainment, also play a significant role in service industries like restaurants, child care, and private households. Among the high-skilled self-employed, one in four who report owning a physicians’ office or a computer design business are foreign-born. Other industries where high-skilled self-employed immigrants are concentrated are legal services, architectural and engineering, and accounting services.

Earnings are another relevant measure of economic contributions and can be used as a gauge for how well self-employed immigrants do in the U.S. labor market. Although unadjusted average annual earnings are lower among self-employed immigrants, once earnings relevant factors are accounted for, the immigrant-native earnings gap is no longer statistically significant. There are two exceptions. First, low-skilled self-employed immigrants have about 11 percent higher earnings than observationally similar U.S.-born low-skilled business owner. Second, high-skilled immigrant business owners who have been in the United States for 15 or fewer years have statistically lower earnings than their U.S.-born counterparts. Although the estimates suggest a substantial earnings penalty for limited English proficiency, especially among the least educated immigrant business owners, the results point toward success on par with their U.S.-born counterparts.

References

Andersson, P., and Wadensjö, E. (2005) “Self-Employed Immigrants in Denmark and Sweden: A Way to Economic Self-Reliance?” IZA Discussion Paper No. 1130.

Antecol, H., and Schuetze, H. J. (2007) “Immigration, Entrepreneurship and the Venture Start-Up Process.” In S. C. Parker, Z. J. Acs, and D. R. Audretsch (eds.) International Handbook Series on Entrepreneurship, Vol. 2. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Borjas, G. (1986) “The Self-Employment Experience of Immigrants.” Journal of Human Resources 21 (Fall): 487–506.

Clark, K., and Drinkwater, S. (2000) “Pushed Out or Pulled In? Self-Employment among Ethnic Minorities in England and Wales.” Labour Economics 7: 603–28.

__________ (2010) “‘Patterns of Ethnic Self-Employment in Time and Space: Evidence from British Census Microdata.” Small Business Economics 34 (3): 323–38.

Cummings, S. (1980) Self-Help in Urban America: Patterns of Minority Business Enterprise. New York: Kenikart Press.

Decker, R.; Haltiwanger, J.; Jarmin, R.: and Miranda, J. (2014) “The Role of Entrepreneurship in U.S. Job Creation and Economic Dynamism.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 28 (3): 3–24.

Fairlie, R. W. (2008) “Estimating the Contribution of Immigrant Business Owners to the U.S. Economy.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy.

Fairlie, R. W., and Meyer, B. D. (2003) “The Effect of Immigration on Native Self-Employment.” Journal of Labor Economics 21 (3): 619–50.

Fairlie, R. W., and Lofstrom, M. (2015) “Immigration and Entrepreneurship.” In B. Chiswick and P. Miller (eds.) Handbook on the Economics of International Immigration, 877–911. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Fairlie, R. W.; Zissimopoulos, J.; and Krashinsky, H. A. (2010) “The International Asian Business Success Story: A Comparison of Chinese, Indian, and Other Asian Businesses in the United States, Canada, and United Kingdom.” In J. Lerner and A. Shoar (eds.) International Differences in Entrepreneurship, 179–208. Chicago: University of Chicago Press and National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hart, D. M., and Acs, Z. J. (2011) “High-Tech Immigrant Entrepreneurship in the United States.” Economic Development Quarterly 25 (2): 116–29.

Holcombe, R. G. (1998) “Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth.” Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 1 (2): 45–62.

Hunt, J., and Gauthier-Loiselle, M. (2010) “How Much Does Immigration Boost Innovation?” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2 (2): 31–56.

Kerr, W. R., and Lincoln, W. F. (2010) “The Supply Side of Innovation: H-1B Visa Reforms and U.S. Ethnic Invention.” Journal of Labor Economics 28 (3): 473–508.

Lazear, E. P. (2002) “Entrepreneurship.” NBER Working Paper No. 9109.

Lofstrom, M. (2002) “Labor Market Assimilation and the Self-Employment Decision of Immigrant Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Population Economics 15 (1): 83–114.

OECD (2005) SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2005. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Reynolds, P. (2005) Entrepreneurship in the United States: The Future Is Now. New York: Springer.

Schuetze, H. J. (2009) “Immigration Policy and the Self-Employment Experience of Immigrants to Canada.” In T. McDonald, E. Ruddick, A. Sweetman, and C. Worswick, C. (eds.) Canadian Immigration: Economic Evidence for a Dynamic Policy Environment. Toronto: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Schuetze, H. J., and Antecol, H. (2007) “Immigration, Entrepreneurship, and the Venture Start-Up Process.” In S. Parker (ed.) The Life Cycle of Entrepreneurial Ventures: International Handbook Series on Entrepreneurship, Vol. 3. New York: Springer.

U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy (2011) “Research and Statistics.” Available at www.sba.gov/advocacy/847.

Notes

1For more details, see Fairlie and Lofstrom (2015).

2It may also be due to more secure property rights in the United States and greater freedom.

3Results not shown but available upon request.