The economic case for free immigration is nearly identical to the case for free trade. They both rely on a greater division of labor based on comparative advantage to ensure that allowing the free movement of goods and services or the free movement of people results in greater global wealth. Estimates of the global gains that could be achieved by the global adoption of an open immigration policy are massive, ranging from 50 to 150 percent of world GDP (Clemens 2011). Even a migration of just 5 percent of the world’s poor to wealthier countries would boost world GDP by more than could be gained by completely eliminating all remaining trade barriers to goods, services, and capital flows (Clemens 2011).

How Free Immigration Could Impact Institutions and Culture

The case for free immigration is more complicated than the basic economic case for free trade because immigrants, unlike goods, can impact host countries’ institutions and culture. Immigrants can protest, agitate for political change, promote ideas that can change native-born citizens’ thinking, and, in some cases, participate directly in the political process, in ways that ultimately might change the institutional environment in their destination country.

Classical liberals have long recognized the benefits of free immigration but have also been concerned with how immigrants might impact institutional evolution. Ludwig von Mises (1927: 137) noted:

The liberal demands that every person have the right to live wherever he wants. This is not a “negative” demand. It belongs to the very essence of a society based on private ownership of the means of production that every man may work and dispose of his earnings where he thinks best.

However, Mises recognized that immigrants might turn the machinery of the state against the natives. Thus, he concluded: “Only the adoption of the liberal program could make the problem of immigration, which today seems insoluble, completely disappear” (p. 142).

Fredrich Hayek shared similar concerns that a more open borders policy could result in political blowback that might lead to less free societies, but for him the worry was the potential backlash from the native-born population.

While I look forward, as an ultimate ideal, to a state of affairs in which national boundaries have ceased to be obstacles to the free movement of men, I believe that within any period with which we can now be concerned, any attempt to realize it would lead to a revival of strong nationalist sentiments and a retreat from positions already achieved [Hayek 1998: 58].

These fears have been rekindled in the latest debate among economists about the economic impact of immigration. George Borjas (2015: 961) asked: “What would happen to the institutions and social norms that govern economic exchanges in specific countries after the entry/exit of perhaps hundreds of millions of people?” He says, “We know little . . . about how host societies would adapt to the entry of perhaps billions of new persons” (p. 967). He then discusses how varying degrees of importation of bad institutions could impact the projected global gain from unrestricted immigration. He concludes that “general equilibrium effects can easily turn a receiving country’s expected (static) windfall from unrestricted migration into an economic debacle” (Borjas 2015: 972). In short, if immigrants bring their institutional values with them to destination countries, the expected gains from a global open borders policy would disappear or even turn negative.

Measuring How Immigrants Impact Institutions

Though dressed up in a mathematical model, Borjas’s (2015) argument is nothing more than a conjecture. He offers no empirical evidence that immigrants actually destroy institutional quality in destination countries. But his conjecture has led to a new stream of research attempting to measure whether immigrants harm destination country institutions in a way that decreases productivity. However, each empirical estimation has its limitations, since we do not live in a world with open borders.

Clark et al. (2015) examined how existing stocks and flows of immigrants impacted economic institutions over a 20-year period, finding that greater immigration was associated with a larger improvement in a measure of economic institutions associated with better economic outcomes. Clemens and Pritchett (2016) use data on immigrant productivity, economic assimilation, and how both of these factors change at higher levels of migrant population, to project that current global migration levels are far below optimal even when resulting institutional and cultural changes are included. Both of these studies are important advances beyond Borjas’s conjectures, but Clark et al. are limited by the fact that they are studying the impact of stocks and flows that arose from a system of restricted migration. Clemens and Pritchett are limited by the fact that the transmission and assimilation parameters are measured by gaps and changes in immigrants’ income earnings. Thus, income gaps and changes in those gaps may tell us little about external effects of immigrants on the productivity of natives if deterioration in institutional quality is the primary channel through which immigrants impact the productivity of others.

Mass Immigration in Israel: A Natural Experiment

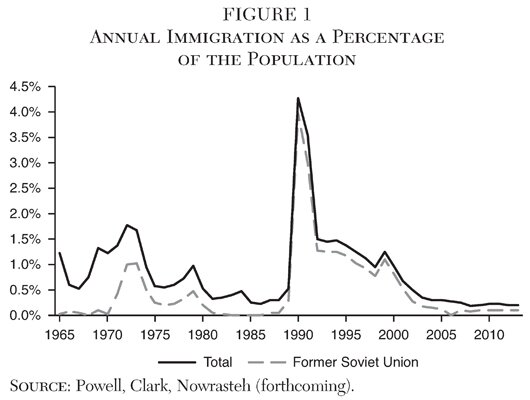

This article summarizes a new attempt by Powell, Clark, and Nowrasteh (forthcoming) to measure the institutional impact of mass migration using the case study of Israel in the 1990s. The first part of that decade saw a 20 percent increase in Israel’s population due to an influx of Jews from the former Soviet Union (FSU) (Figure 1). In 1990 alone, Russian immigration increased the population by 4 percent. For comparison, immigration to the United States at the turn of the 20th century averaged 1 percent annually (Friedberg 2001: 1375). This mass migration occurred because the Soviet Union relaxed emigration restrictions and subsequently collapsed, while Israel has long had the Law of Return, which allows all Jews worldwide to immigrate regardless of their country of origin.

This mass migration has two features that make it particularly well suited to analyze the negative importation of social capital that could undermine institutions. First, all of these immigrants were coming from the FSU, a country with a more than 70-year history of socialism and associated anti-capitalist propaganda. If the immigrants were to agitate politically based on their origin country’s ideology, it would clearly have the potential to undermine Israel’s democratic and relatively capitalistic institutions. Second, Israel provides the easiest situation for immigrants to directly impact the political process. The Law of Return allows Jewish immigrants to have full citizenship, including the right to vote and to run for office, from the day they arrive in Israel.

There are also two drawbacks for using Israel as a case study. First, and most obviously, Israel’s open borders policy applies only to Jews. Second, these migrants probably possess a different mix of human capital from what normally could be expected of mass migrations from developing countries. However, there is good reason to believe that despite the Jewish makeup of these immigrants, they represent a case of normal immigration that could serve to undermine institutions.

The Law of Return stipulates that all Jews, as well as any gentile spouses of Jews, non-Jewish children and grandchildren of Jews, and their spouses, are eligible to migrate to Israel. Thus, under the Law of Return, the right of migration and citizenship applies to many people who are not Jewish according to halakhah (Jewish religious law). As a result, the majority of the immigrants from the FSU were non-religious Jews. Among the former Soviet migrants, 74 percent identified as secular, and only 1.4 percent identified as strongly religious (Al-Haj 2004: 102). The immigrants were also linguistically and culturally distinct. In the 1979 Soviet census, only 14.2 percent of the Soviet Jewish population claimed a Jewish language as their mother tongue, and another 5.4 percent claimed it as a second language, while 97 percent of Soviet Jews spoke Russian (Al-Haj 2004: 74). Much like migration from developing countries today, this wave of immigration was motivated not by Zionist ideology but by pragmatic cost-benefit considerations. Like other typical migration flows, the members of this group were motivated mainly by “push factors” in their home countries (Al-Haj 2004: 100).

The immigrants immediately began to participate in Israeli institutional evolution. They influenced electoral outcomes through the creation of their own immigrant parties, while not being adverse to switching loyalties between the main preexisting parties in order to increase their political leverage. By 1996 an immigrant political party was part of the ruling coalition government. Overall, as one scholar assessed the situation, “FSU immigrants in Israel have successfully penetrated the political system at the group level and become a legitimate part of the national power center within a few years of their arrival” (Al-Haj 2004: 209). However, rather than import their origin country’s institutions to Israel, the immigrants’ political participation coincides with a large move in Israeli institutions toward free-market policies and away from socialism.

Economic Freedom in Israel

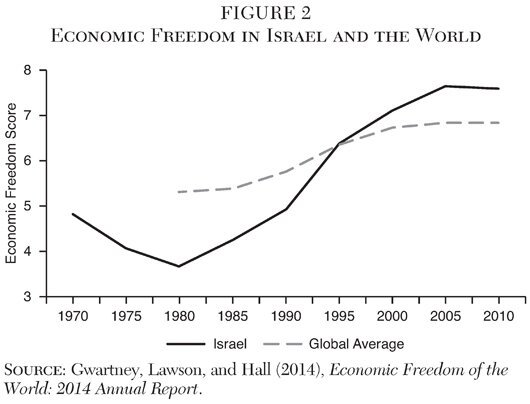

According to the 2014 Economic Freedom of the World (EFW) report (Gwartney, Lawson, and Hall 2014), Israel made major improvements in its economic freedom while the mass migration from the FSU was occurring. The EFW index is a reasonable proxy for economic institutions that could impact a country’s production function. It has been used in more than 100 articles finding that higher levels of, or improvement in, economic freedom are associated with higher income levels, greater economic growth, and a host of other improved economic outcomes (De Haan, Lundström, and Sturm 2006; Hall and Lawson 2013).

The EFW index incorporates 43 variables across 5 broad areas: the size of government; legal structure and property rights; sound money; freedom to trade internationally; and regulation of credit, labor, and business. At its most basic level, the EFW index measures the extent to which individuals and private groups are free to buy, sell, trade, invest, and take economic risks without interference by the government. To score high on the EFW index, a nation must keep taxes and spending low, protect private property rights, maintain stable money, keep the borders open to trade and investment, and exercise regulatory restraint in the marketplace. The EFW index has a lowest possible score of 0 and a highest possible score of 10.

Prior to the mass migration from the former Soviet Union, Israel scored a 4.92 out of a possible 10 on the EFW Index. That was below the world average of 5.77, resulting in a rank of only 92nd freest. As Figure 2 illustrates, Israel had always scored below the world average in economic freedom until the mid-1990s. But during the decade of mass migration, Israel improved its economic freedom score by 45 percent (more than two full points). By 1995 it had surpassed the global average in economic freedom, and by 2000 it had climbed 38 spots to rank 54th freest. Economic freedom continued to improve by another half a point, as immigration waned in the early 2000s, reaching a peak of 7.6 in 2005, ranking 45th in the world. The reforms have held, and Israel’s economic freedom score has remained largely unchanged over the last decade. The overall increase of economic freedom in Israel during the period of mass migration and the five years immediately following it resulted in Israel catapulting from 15 percent below the global average to 12 percent above it and improving its ranking among countries by 47 places.

Conclusion

Any example from an individual country must be interpreted with caution. This study finds that unrestricted mass migration from an origin country with inferior political and economic institutions coincided with an enhancement of economic institutions in the destination country. Correlation is not causation. However, the Israeli political campaigns attempting to get the immigrant vote clearly used anti-socialist propaganda in the belief that the immigrants would rebel against the institutions of their origin country. The preexisting political equilibrium was also a deadlock between the main left and right parties at the time of the migration, so the immigrants clearly impacted the position of the median voter. At a minimum, Israel presents a case where mass migration failed to harm institutions in a way that many prominent social scientists fear such a migration would.

This finding in no way proves that in every case unrestricted migration would not harm destination country institutions. However, as a complement to Clark et al. (2015), which, in a cross-country empirical analysis, found that existing stocks and flows of immigrants were associated with improvements in economic institutions, it should increase our skepticism of claims that unrestricted migration would necessarily lead to institutional deterioration. Indeed, there may be “trillion dollar bills” that the global economy could gain through much greater migration flows.

References

Al-Haj, M. (2004) Immigration and Ethnic Formation in a Deeply Divided Society: The Case of the 1990s Immigrants from the Former Soviet Union in Israel. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

Borjas, G. J. (2015) “Immigration and Globalization: A Review Essay.” Journal of Economic Literature 53 (4): 961–74.

Clark, J. R.; Lawson, R.; Nowrasteh, A.; Powell, B.; and Murphy, R. (2015) “Does Immigration Impact Institutions?” Public Choice 163: 321–35.

Clemens, M. (2011) “Economics and Emigration: Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk?” Journal of Economics Perspectives 25: 83–106.

Clemens, M., and Pritchett, L. (2016) “The New Economics Case for Migration Restrictions: An Assessment.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 9730.

De Haan, J.; Lundström, S.; and Sturm, J. (2006) “Market-Oriented Institutions and Policies and Economic Growth: A Critical Survey.” Journal of Economic Surveys 20: 157–91.

Friedberg, R. M. (2001) “The Impact of Mass Migration on the Israeli Labor Market.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 116: 1373–1408.

Gwartney, J.; Lawson, R.; and Hall, J. (2014) Economic Freedom of the World: 2014 Annual Report. Vancouver, B.C.: Fraser Institute.

Hall, J., and Lawson, R. (2013) “Economic Freedom of the World: An Accounting of the Literature.” Contemporary Economic Policy 32: 1–19.

Hayek, F. A. (1998) Law, Legislation, and Liberty, Volume 2: The Mirage of Social Justice. London, U.K.: Routledge.

Mises, L. V. (1927) Liberalism. New York: Foundation for Economic Education.

Powell, B.; Clark, J. R.; and Nowrasteh, A. (forthcoming) “Does Mass Immigration Destroy Institutions? 1990s Israel as a Natural Experiment.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization.