Policymakers should

9. Dealing with ISIS in Iraq and Syria

• understand that ISIS does not pose an existential threat to the United States;

• accept that U.S. military intervention in Syria and Iraq is unlikely to create a stable postconflict environment;

• avoid escalation of the current military campaign against ISIS;

• seek instead to contain the group with air power, while encouraging local and regional partners to roll back the group on the ground; and

• actively pursue a negotiated political transition to end Syria’s civil war.

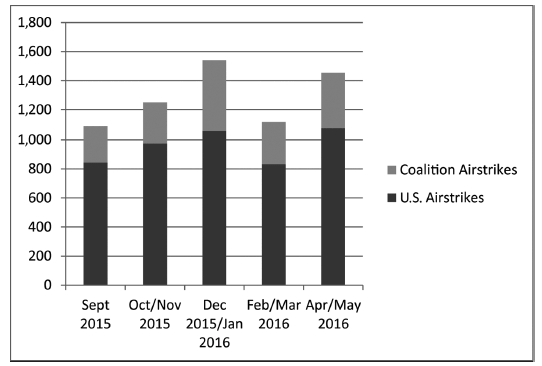

Since August 2014, the United States and a coalition of more than 60 countries have been engaged in an open-ended military campaign against the (self-proclaimed) Islamic State (ISIS) inside Iraq and Syria. Yet, as Figure 9.1 illustrates, the United States has borne the brunt of this effort. (In 2015 and 2016, the United States launched over 12,000 airstrikes, at a cost of more than $9.3 billion to U.S. taxpayers.) In addition, as of July 2016, the United States had at least 5,000 troops on the ground in Iraq and a smaller number of special operations forces in Syria, coordinating airstrikes and training Iraqi government and Syrian rebel forces to fight ISIS more effectively.

Progress against ISIS has been slow but steady. The group has lost a substantial amount of territory — including the key city of Ramadi in Iraq; and while it was initially able to bring in enough recruits to offset losses from the air campaign, recruitment has dropped in 2016, denying the group much-needed fighters. Nonetheless, ISIS's use of innocent civilians as human shields has constrained the U.S. air campaign, and gains on the ground by U.S. coalition partners have been limited. Kurdish forces remain the only truly effective ground force in Syria. Iraqi forces have made slow but steady progress since the army's humiliating 2014 defeat by ISIS, retaking several key towns, but much of that progress can be attributed to independent sectarian militias rather than official government forces, a factor that will substantially complicate postconflict stabilization. Meanwhile, attacks in Paris, Brussels, and Orlando make clear that even as it is losing at home, ISIS can inspire terrorist attacks well outside its own self-proclaimed caliphate.

Figure 9.1

Recent U.S. and Coalition Airstrikes against ISIS

SOURCE: All data from U.S. Department of Defense, Operation Inherent Resolve website: http://www.defense.gov/News/Special-Reports/0814_Inherent-Resolve.

Yet, ISIS itself does not pose a major threat to the United States. As a proto-state, the group is unable to carry out any form of conventional military attack against the United States. And as with all terrorist groups, ISIS's ability to hurt Americans is small. There is a key difference between ISIS and other groups like al Qaeda: the latter planned and coordinated its attacks centrally; but many of the Western attacks attributed to ISIS — including mass shootings in San Bernardino, California, in December 2015, and Orlando, Florida, in June 2016 — can best be described as inspired by ISIS, rather than directed by it. In both those cases, the perpetrators had no prior links with ISIS and had not been in contact with the group prior to their attacks.

Attacks directed or planned by ISIS itself remain unlikely inside the United States, which is less vulnerable to infiltration from abroad than many European nations. The sudden mushrooming of ISIS affiliates around the globe in 2015 and 2016 is likewise not as threatening as it might seem. In fact, most of those groups already existed as local or regional terrorist groups. For example, the ISIS affiliate credited with bringing down a Russian airliner in Egypt began life as the separatist group Province of Sinai; and Nigeria's Boko Haram was active more than a decade before the rise of ISIS. Most of the groups that have sworn allegiance to ISIS have limited, local aims.

Nonetheless, there are other strategic concerns: though ISIS poses only a limited risk to the United States, it could threaten the stability of various Middle Eastern states. In addition to its role in violent insurgencies in Iraq, Syria, and Libya, ISIS has claimed responsibility for bombings and attacks throughout the Middle East, including targeting tourists in Tunisia and Egypt, and bombing airports, mosques, and other public areas in Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Egypt, and Lebanon. Though not solely attributable to ISIS, the Syrian civil war has created the worst refugee crisis since World War II, and while much of the attention has focused on Europe, most refugees are fleeing to nearby countries. The resources of many of the region's poorest countries are being stretched by this influx: 20 percent of Lebanon's current population is Syrian refugees.

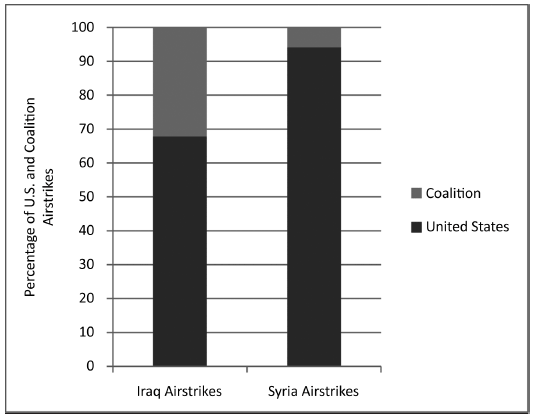

Given the predominantly local threat of ISIS, it is perhaps surprising how little effort regional states have so far committed to the fight against it. As Figure 9.2 illustrates, the disparity between U.S. airstrikes and coalition airstrikes — carried out by several North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) member states as well as local states such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Jordan — is even starker in Syria than in Iraq. Progress in Syria has been impeded by some states' insistence on the removal of Syria's Bashar al-Assad, which would likely only empower ISIS in the near term. Indeed, many of America's partners, including Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Qatar, were heavily involved in funding and arming anti-Assad rebels inside Syria and have proved reluctant to shift their focus to ISIS. Turkey's long-running conflict with its own Kurdish minority has further undermined the anti-ISIS campaign, as the Erdogan government has chosen to bomb ISIS and various Kurdish groups inside Syria simultaneously.

Figure 9.2

U.S. vs. Coalition Commitments in Iraq and Syria (2014–2016)

SOURCE: All data from U.S. Department of Defense, Operation Inherent Resolve website: http://www.defense.gov/News/Special-Reports/0814_Inherent-Resolve.

Some have suggested that regional states' apathy should be offset by increased American military involvement in Syria and Iraq. But even if we ignore the fact that that is not a proportional response to the limited threat ISIS poses to the United States, it is also no substitute for the involvement of local and regional actors in the fight. The lessons of the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the 2011 Libya intervention are clear: the United States can achieve military victory with ease, but creating lasting stability is far more difficult — and impossible without the cooperation of local and regional actors.

In the case of ISIS, the U.S. military could undoubtedly defeat the group with a large conventional ground force, though it would be costly. However, the withdrawal of U.S. forces afterward would leave a vacuum, offering the prospect of a resurgent ISIS or of similar groups rising to take its place. To avoid such chaos, postconflict stabilization would require a potentially decades-long peacekeeping operation. Recent experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan, however, have confirmed that long-term nation-building missions are likely to fail. They are deeply unpopular among the Americans who will be paying the costs and are resented by local actors who object to outsiders meddling in their political affairs.

Similar problems plague many of the proposed solutions to the Syrian problem. No-fly zones, including so-called "no bombing zones," or "humanitarian zones," may seem relatively costless and valuable humanitarian acts. But in practice, they require a substantial commitment of both air and ground forces to maintain. In Syria, the creation of such zones would bring U.S. forces into direct military confrontation with the Assad regime and its Russian backers. Related proposals — such as committing many more special operations forces inside Syria — have comparable problems. All these options are prone to "mission creep."

Ultimately, a policy similar to the Obama administration's initial strategy — containing ISIS with airpower, while encouraging local and regional partners to roll back the group on the ground — remains the best approach. The United States should also push other coalition members to contribute more to the air campaign. After all, many of those countries are more threatened by ISIS than the United States itself; shifting at least some of the responsibility for military action against ISIS to those states would produce a more durable campaign and spread the burden of such action more evenly and effectively. And while the military campaign does have the potential to undermine the growth of ISIS inside Iraq and Syria, policymakers must be aware that no military campaign can prevent homegrown or lone wolf–style attacks inspired by ISIS. Dealing with that threat remains the job of the intelligence and law enforcement communities, not the military.

The prerequisite to successfully undermining ISIS is a coherent political solution, involving regional and local players, in both Syria and Iraq. Of course, even if regional players are involved, chaos may still result in Syria. States such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar have already worsened the situation in Syria, but their existing ties to the conflict mean that little can be achieved without their continued involvement. The same applies to other parties to the Syrian conflict, including Russia, the United States, moderate Syrian rebel groups, Kurdish factions, and even the remnants of the Assad regime. Multilateral coordination between all the stakeholders — not just on fighting ISIS but on the political negotiations that will determine Syria's future — will improve the prospect of eventual stability. ISIS is widely despised, and though historical enmity, regional rivalries, and distrust all impede effective cooperation between these parties, the Syrian civil war and Iraq's political turmoil are the bigger obstacles.

The United States can do little to improve the political situation in Iraq other than encourage much-needed reforms, particularly on issues of corruption and sectarianism. The United States can provide diplomatic support, but these are challenges the government of Haider al-Abadi must overcome alone. In contrast, there are several possible diplomatic paths to ending the Syrian civil war, grounded in the United Nations' Geneva process, which seeks to create a new governing structure for Syria. With strong U.S. support and initiative on the diplomatic front, a successful transition is possible in Syria. Certainly, it will be difficult to overcome the differences between the states that support the Assad regime and those that oppose it. A deal will likely require unpleasant compromises, such as a lengthy transition period that initially leaves Assad in power. And implementation will rest on the ability of external actors — chiefly the Saudis, Russians, Iranians, Turks, and Qataris — to force their proxies within Syria to comply, which is no simple feat. But the basic shape of a deal that once seemed unthinkable has already been hammered out in negotiations, and the agreement on cessation of hostilities in March 2015 implies that such a deal could be achieved.

Another option that could emerge from Geneva is some form of federalism, or even de facto partition of Syria, creating an Alawite rump state around Damascus, a Kurdish region in the country's north, and a Sunni-majority zone elsewhere. Even without an overarching peace settlement, partition would lower the overall levels of violence and refugee flows and would create time to conduct broader negotiations on the future of the Syrian state. That outcome may be easier to achieve than a full peace deal or federalism, but partition will not give all parties inside Syria a stake in seeing ISIS destroyed: the Assad regime, far from ISIS-controlled territory, would probably prefer to sit out the fight, hoping that ISIS weakens other groups enough for the regime to regain territory. Thus, a negotiated transition remains the best option for Syria.

Ultimately, all roads to decisively defeating ISIS in Iraq and Syria begin with a solution to Syria's appallingly violent civil war. In addition to the current U.S. role in containing ISIS militarily, U.S. policymakers should focus their efforts on diplomacy and on building the Syrian domestic and regional support necessary to replace ISIS in the long term. This level of involvement is greater than required for U.S. security, given the minimal risk that ISIS poses to Americans. But our involvement is warranted in the interest of resolving a deeply destabilizing conflict, one that the United States is at least partly responsible for starting. Policymakers should refrain from increasing U.S. military intervention — whether in the form of troops on the ground, humanitarian safe zones, or no-fly zones — as such involvement has substantial risks.

The limited military action proposed here will not produce results overnight. Nor can any military approach truly eradicate a terrorist group like ISIS. But this restrained approach is far more likely than other approaches to destroy the group's foothold in Iraq and Syria, while ensuring a stable postconflict environment.

Suggested Readings

Ashford, Emma. "It's Time to Admit That American Intervention Can't Fix Syria." Vox, February 25, 2016.

Borghard, Erica D. "Arms and Influence in Syria: The Pitfalls of Greater U.S. Involvement." Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 734, August 7, 2013.

Lynch, Marc. The New Arab Wars: Uprisings and Anarchy in the Middle East. New York: PublicAffairs, 2016.

McCants, William. The ISIS Apocalypse: The History, Strategy, and Doomsday Vision of the Islamic State. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2015.