Policymakers should

74. NATO Policy

• avoid escalating tensions with Russia, especially along its western border;

• insist that no new members be added to NATO;

• increase pressure on NATO members to fulfill immediately the commitment they made at the 2006 summit to devote at least 2 percent of their gross domestic product to defense;

• begin a phased drawdown of all U.S. forces in Europe and begin the process of transferring full responsibility for European defense to the European Union and other significant European actors, such as the United Kingdom; and

• announce that it is the intention of the United States to withdraw from the North Atlantic Treaty by April 2024, the 75th anniversary of the treaty.

The creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949 represented the most explicit break with America's traditional policy of avoiding foreign alliances and generally charting a noninterventionist course. Being drawn into two major wars in little more than a generation — and especially the psychologically devastating attack on Pearl Harbor — had struck a fatal blow to a noninterventionist foreign policy. Even prominent noninterventionists such as Sen. Arthur Vandenberg (R-MI) concluded that the world had changed and that "isolationism" (a poisonous misnomer) was no longer an appropriate policy for the United States. Joining NATO, the ultimate in "entangling alliances" with European powers, confirmed the extent of the shift in Washington's policy and American attitudes.

It was hard to dispute the "world has changed" argument. There was no semblance of a European or a global balance of power in the late 1940s or early 1950s. Central and Eastern Europe were under the domination of the Soviet Union, a ruthless totalitarian power that posed an expansionist threat of unknown dimensions. Western Europe, although mostly democratic, was badly demoralized from the devastation of World War II and the looming Soviet menace. Even prominent noninterventionists such as Sen. Robert A. Taft (R-OH) were not prepared to cut democratic Europe loose in such an environment. But Taft wanted merely to offer the Europeans a security guarantee, not have the United States take the fateful step of joining NATO and assuming virtually unlimited leadership duties for an unknown length of time. Subsequent developments validated his wariness.

NATO partisans insisted that the world changed with World War II and that the new paradigm required extensive U.S. leadership. The problem with their analysis, especially as the decades have passed, is that they seem to assume that change is a single major event and everything thereafter operates within the new paradigm. That assumption is totally false. Change is an ongoing process. Today's Europe is at least as different from the Europe of 1949 as that Europe was from pre–World War II Europe. Yet the institutional centerpiece, NATO, and much of the substance of U.S. policy remain the same.

Even though Russia is now a weakened power with regional ambitions rather than a malignantly expansionist totalitarian state with global ambitions, NATO officials treat Moscow as though little has changed since the days of Leonid Brezhnev, if not Joseph Stalin. Yet Russia, with 142 million people, has less than 60 percent of the population of the old Soviet Union — and it is an aging population with a declining average lifespan. The Russian economy is likewise much smaller (only $1.3 trillion), and it is both fragile and one dimensional, with a heavy dependence on energy exports. In short, Russia is simply too weak to pose a conventional challenge to much of Europe.

Nevertheless, U.S. officials have viewed Moscow's annexation of Crimea and its support for pro-Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine as the harbinger of much wider aggression. A more plausible interpretation is that those moves were an effort by Vladimir Putin's government to strengthen security along Russia's western border against what Russian leaders see as a dangerous eastward expansion of NATO.

Instead of responding as the United States and its NATO allies have done with military exercises and new military deployments in Eastern Europe, they should move more cautiously and be mindful of Russia's longstanding security concerns in that region.

U.S. and Russian interests on a variety of important issues, including counterterrorism, coincide more than they conflict, so maintaining decent relations with Moscow makes good strategic sense. It also would be the height of bitter irony if, having escaped a direct military clash with the Soviet Union (a truly dangerous adversary) during the Cold War, NATO stumbled into conflict with a mundane Russia because of a needlessly inflexible and confrontational approach. Yet that is now a real danger unless U.S. and NATO policy changes dramatically.

One relatively easy step that the United States can take is to veto any move to add new members to NATO. Some candidates are not necessarily in Russia's security zone. The newest alliance member, for example, Montenegro, is in the Balkans. The most discussed potential members, though, such as Georgia and Ukraine, would trigger a crisis with Moscow. Only the most reckless policymakers should wish to go down that path. Moreover, adding an assortment of small, militarily insignificant "allies" does nothing to benefit America's security and well-being. Indeed, when those small security dependents are on bad terms with a great power neighbor, they can greatly endanger America's security by triggering an unnecessary armed conflict. We already have that risk with the three Baltic republics, given their fraught relations with Moscow. Adding Georgia or Ukraine to the alliance would greatly compound the danger.

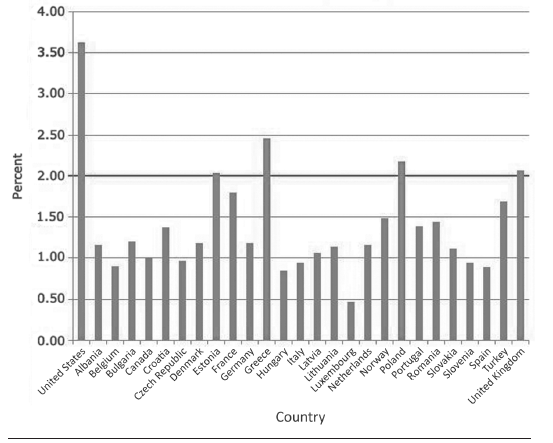

Although the United States should push NATO to adopt a more conciliatory policy toward Russia, Washington also needs to make clear to the other alliance members that the days of free riding on America's security exertions have ended. There is an especially annoying gap between the rhetoric of those European members who cite a rising Russian security threat and their commitment to fulfilling the pledge made at the 2006 summit to devote at least 2 percent of annual gross domestic product (GDP) to defense. Some still fall short — often far short — of that amount. Only 4 of the 28 members (other than the United States) fulfill the 2 percent pledge, and 2 of them (Estonia and Poland) have done so just recently (see Figure 74.1). Indeed, several key NATO members, including Germany, Italy, and Spain, hover around 1 percent. If NATO's European members want to present a credible deterrent to Russia, they need to do more — unless, of course, they are simply relying on the United States to handle their security needs.

Washington has complained about the lack of burden sharing for decades and gained little satisfaction. When the European allies have not ignored U.S. protests entirely, they've made paper promises — as with the 2 percent pledge — that are soon forgotten. The United States needs to move beyond burden sharing to burden shifting. Europe is no longer a collection of demoralized, war-ravaged waifs, as it was when NATO was created. Most of the European democracies are now banded together in the European Union (EU), with a population and collective GDP larger than that of the United States. Although they are troubled by the turbulence in the Middle East and the occasional growls of the Russian bear, they are capable of handling both problems. As noted, Putin's Russia is a pale shadow of the threat once posed by the Soviet Union. The EU has three times the population and an economy more than 10 times that of Russia. Although Britain's probable departure following the Brexit vote will shrink the EU modestly, it remains an impressive collection of major powers. The primary reason that the EU countries have not done more to manage the security of their own region is that the United States has insisted on taking the dominant role — and paying a large portion of the costs. From the standpoint of American interests, that is a myopic, self-destructive policy that needs to change immediately.

Figure 74.1

NATO Country Defense Spending as a Share of GDP, 2015

SOURCE: NATO, The Secretary General's Annual Report, 2015.

The new administration should move on two policy fronts. First, it should explicitly reverse U.S. policy and strongly encourage the EU to take on security responsibilities. That change also means that the EU needs to work with NATO countries that are not EU members (e.g., Turkey) or will cease being part of the union (Britain). Among other steps in this transfer of security responsibilities, the next commander of NATO forces should be a European, not an American.

Such burden shifting is long overdue. In terms of geographic proximity alone, the European powers should be more concerned than the United States about developments in both Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Yet we currently have the opposite situation. Countries that are directly exposed to developments in those regions defer to the United States for crucial policy decisions, and America incurs a disproportionate degree of the costs and risks of implementing NATO's policies. That situation needs to change.

NATO's overall strategic orientation has become alarmingly diffuse. When one of the most prominent missions of the "North Atlantic" alliance is a seemingly endless counterinsurgency and nation-building venture in Afghanistan, that suggests NATO's leaders have lost their strategic bearings. Although Washington was able to entice and cajole some of the European members to participate in that out-of-area intervention, that achievement was in the best interests of neither the United States nor those countries. A new European security entity should, and would be more likely to, focus on the more pressing security needs of democratic Europe and its surrounding neighborhood instead of being a junior partner in geographically remote, quixotic crusades.

In addition to the general policy shift, the new administration must commence a significant redeployment of U.S. forces from the European theater. Within a four-year period, the United States ought to withdraw all of its ground forces from Europe. It should also reduce its naval and air forces there by at least 50 percent by that same target date. Such a schedule will convey to the European allies both the seriousness of Washington's intentions and the urgency of a constructive response on their part to replace those forces.

The ultimate goal of the policy shift should be nothing less than the withdrawal of the United States from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. The new administration should immediately inform the other NATO members of Washington's intention to execute that withdrawal by April 2024, the 75th anniversary of the treaty. Seventy-five years is an exceedingly long period for any policy to be relevant and beneficial, and America's NATO membership is no exception. It is important not to extend the withdrawal process beyond a 2024 deadline. A longer time frame would merely tempt the European allies to spend the first several years lobbying the United States to reverse its decision. The 2024 deadline gives the allies sufficient time to forge a credible defense and foreign policy successor — if they move promptly to adjust to the new reality.

NATO was created to meet a specific threat in a specific setting. The alliance provided a needed U.S. security shield to protect vulnerable key European democratic powers that had not yet recovered from the devastation of World War II and faced a large, extremely dangerous, totalitarian adversary in the form of the Soviet Union. But what should have been an emergency departure from America's wise tradition of avoiding entangling alliances has become a permanent, needlessly risky burden in a vastly changed world. With today's NATO, the United States is obligated to defend 27 fellow members — most of which are not strategically important to this country. Furthermore, most of the newer members are so small as to provide no meaningful addition to America's own military strength. That characteristic, combined with the dicey relations that several of them have with larger neighbors, makes them strategic liabilities, not strategic assets. Equally troubling, some of the members, especially Turkey and Hungary, are exhibiting such pronounced authoritarian tendencies that it is not always easy to distinguish their behavior from that of outright autocratic regimes like Putin's Russia. It would be awkward, at the very least, to risk America's security and well-being to defend such clients.

NATO is an institutional dinosaur that has outlived whatever usefulness it might once have had. The new administration's short-term goal should be to repair relations with Russia and reverse the slide toward a new cold war. The incoming administration also must increase pressure on the European members to fulfill the defense spending commitments they have already made. Longer term, U.S. policymakers need to change the terms of the policy debate, transferring to the European allies full responsibility for their own defense and the security of their region and extricating the United States from an obsolete security obligation.

Suggested Readings

Bandow, Doug. "NATO Isn't a Social Club: Montenegro, Georgia, and Ukraine Don't Belong." Forbes, July 8, 2016.

Carpenter, Ted Galen. "NATO at 60: A Hollow Alliance." Cato Policy Analysis no. 635, March 30, 2009.

---. "NATO's Mounting Internal Challenges." Aspenia Online, July 9, 2016.

---. "NATO's Worrisome Authoritarian Storm Clouds." Mediterranean Quarterly 26, no. 4 (December 2015): 37-48.

Menon, Rajan. The End of Alliances. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Preble, Christopher. "Our Freeloading Allies," Cato at Liberty, May 29, 2014.