Policymakers should

72. Relations with Russia

• be concerned about the downward spiral in U.S.-Russian relations in recent years;

• understand that Russia’s aggression in Eastern Europe is troubling but not a major threat to the United States;

• avoid taking steps that will increase tensions with Russia, such as arming Ukraine, substantially building up troops in Eastern Europe, or further expanding NATO;

• consider implementing sanctions aimed at impeding Russia’s military modernization in place of current sanctions; and

• seek a constructive working relationship with Russia to address common diplomatic challenges, such as nonproliferation and ending the Syrian civil war.

The U.S.-Russian relationship has long been acrimonious. During the 1990s, with Russia seemingly poised to make a peaceful transition to democracy as a member of the European community, it appeared that the two countries might be able to escape the animosity of the Cold War. History took a different path, however, and recent years have arguably seen a more adversarial relationship than at any point since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Russia's 2014 annexation of Crimea and its involvement in eastern Ukraine's civil war resurrected its pariah-state status and resulted in heavy U.S. and European sanctions, while Russian intervention in Syria since 2015 has complicated the U.S.-led campaign against ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria).

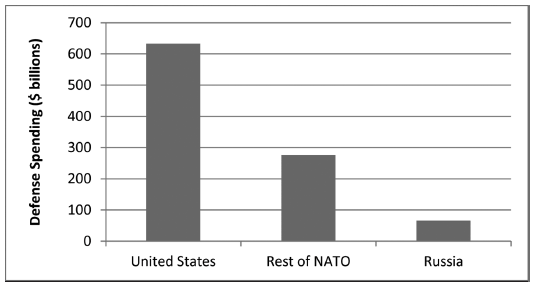

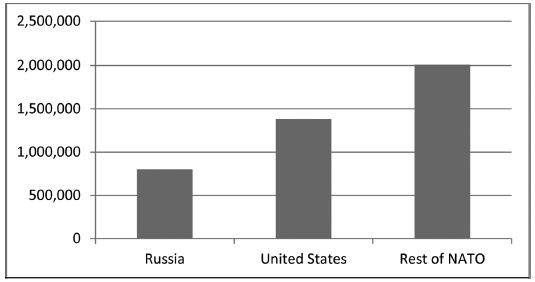

Russia itself poses limited military threat to the United States — primarily through its nuclear arsenal — and even its ability to threaten America's North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies is often exaggerated. By some metrics, Russian military spending appears extremely high (5.4 percent of gross domestic product in 2015), but that number is artificially inflated by Russia's poor economic performance. As Figure 72.1 shows, when real levels of military spending are compared, Russian spending is dwarfed by that of the United States and by the combined spending of the other NATO members. And while Russia's military modernization program has been relatively successful in recent years, reducing the role of conscription and improving readiness, the Russian military lags behind Western forces in technological sophistication. Similarly, the Russian military appears large when compared to small neighboring states like Lithuania or Estonia. Yet as Figure 72.2 illustrates, Russia's active duty military is actually smaller than either that of the United States or the other, combined, NATO allies.

Figure 72.1

Comparative Military Spending (2013)

SOURCE: All data from The International Institute for Strategic Studies. The Military Balance, 2016. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Note: Data for 2013 provide for more accurate budget comparisons (i.e., before the Crimean invasion and the 2014–15 Russian economic shocks). NATO = North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Such simple comparisons, however, cannot adequately convey military readiness or strategic issues. As a recent RAND Corporation wargame noted, Russia could relatively easily and quickly conquer NATO member states in the Baltics; adding more "tripwire" forces to the region would do nothing to alter that outcome. In fact, this is not new. Throughout the Cold War, it was widely known in Western capitals that the Soviet

Figure 72.2

Comparative Active Duty Military Strength (2015)

SOURCE: All data from The International Institute for Strategic Studies. The Military Balance, 2016. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Note: NATO = North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Union could easily conquer much of Europe with conventional forces if it chose to do so. Then and now, NATO's ability to escalate the conflict in the case of a Russian invasion remains its primary deterrent. For that reason, it is highly unlikely that Russia would consider intervention in the Baltics or other NATO member states. Indeed, as many experts have noted, Russia's force posture today gives no indication that it intends such aggression. In short, it is one thing to foment chaos in a troubled neighboring state. It is entirely another to risk intervention in a NATO member state, where U.S. treaty obligations compel a strong military response.

Russian aggression in eastern Ukraine, while abhorrent, thus poses no direct threat to the United States. Nonetheless, poor U.S.-Russian relations should still concern us. Growing tensions in Europe and troop buildups by both sides raise the risk of military conflict and even nuclear escalation. And outside Europe, Russian leaders have the potential to either impede U.S. foreign policy objectives (as in Syria) or enable them (as the Iranian nuclear deal illustrates). Tensions over Ukraine have largely overshadowed and prevented U.S.-Russian dialogue on various important issues, such as nonproliferation and arms control. Improving our relationship with Russia and ratcheting down tensions has the potential to alleviate U.S. foreign policy woes in Europe and elsewhere; it should be a top priority for policymakers.

The relationship has worsened substantially since Russia's military incursions into Ukraine, only six years after similar incursions into neighboring Georgia. Many date the start of the conflict to Russia's March 2014 seizure of the autonomous Ukrainian province of Crimea, home to the headquarters of the Russian Black Sea fleet. But the conflict's roots are much older: given Kiev's role as the cradle of Russian civilization, many Russians never fully accepted the country's independence following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Since independence, Ukraine's ethnic cleavages have produced confrontational and corrupt domestic politics that have alternated between Western-leaning and pro-Russian positions. The Maidan revolution of early 2014 grew out of those frustrations. Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych's refusal, under pressure from Moscow, to sign an association agreement with the European Union prompted street protests that soon turned into a violent revolution. Yanukovych fled to Russia, and a new pro-Western government was inaugurated. The violence was new, but the political divisions were not; indeed, Yanukovych himself had been previously displaced by pro-Western politicians in the largely peaceful 2004 Orange Revolution, only to be reelected president in 2010.

Although Yanukovych's ouster was consistent with the post-Soviet instability of Ukrainian politics, Russia's subsequent annexation of Crimea — followed by its aggressive involvement in arming pro-Russian rebels in eastern Ukraine — was unprecedented. Those actions presented a significant dilemma for American policymakers: Russian aggression did not pose a direct threat to U.S. interests, yet the move was a clear violation of international norms and raised the worrying possibility that Russia might try something similar in NATO member states. The issue was further complicated by Ukraine's corrosive culture of political corruption, the genuine — if minimal — support for the insurgency in the Donbas (eastern Ukraine) by some locals, and Russian official denials of their intervention despite strong evidence to the contrary. There were also more subtle protestations within the Russian establishment that its actions in Ukraine were justified by NATO "encirclement," specifically the violation of Cold War–era promises that NATO would not expand to the east.

After deliberation — and substantial public debate on the issue — the Obama administration ultimately decided against intervention and against arming Ukraine; the next administration would be wise to continue those policies. Two key factors militated against providing arms to Ukraine: (1) concerns about escalating the conflict, and (2) concerns that Ukraine's armed forces were too inefficient and corrupt to effectively use them. The period since then has largely proved the wisdom of that choice: rather than escalating, the conflict has stagnated, and a ceasefire created by the second round of Minsk talks has kept violence at a much lower level since February 2015.

Instead of providing arms, the Obama administration chose to pursue a compartmentalized approach. Outside of Europe, the administration continued a pragmatic policy of diplomacy with Russia on issues like the Iranian nuclear deal. On European issues, in contrast, the administration engaged in a massively ambitious program of targeted sanctions. These sanctions made it difficult for various companies linked to the Russian government or to Kremlin cronies to raise money on international capital markets, to conduct joint ventures with U.S. energy and finance companies, and to access technology used for unconventional drilling projects. Yet the sanctions — even in conjunction with a crippling drop in global oil prices — have been largely ineffectual in altering the Kremlin's calculus on Ukraine. Worse, though they were designed to specifically target elites close to Russia's decisionmakers, the burden of sanctions — and of Putin's agricultural countersanctions — has fallen most heavily on the Russian population. The past two years have largely confirmed long-standing research on sanctions: they are rarely successful in changing state behavior, especially on issues of war and peace.

The difficult truth is that this failure leaves few good policy options on Ukraine. Moreover, any strategy that relies on coercion or threats — such as placing large numbers of troops in Europe — is unlikely to improve relations. Russian foreign policy decisions reflect Vladimir Putin's own insecurities, both international and domestic. The Kremlin fears looking weak to domestic audiences and has stoked nationalist and pro-Soviet sentiments in recent years to compensate for poor economic performance. In many ways, Russia fears being treated as if it is no longer a "great power," a fear that is worsened by NATO expansion. Increasing the Kremlin's perception of external threat is likely to result only in intransigence and further saber rattling, keeping tensions high in Europe and impeding U.S.-Russian cooperation on other issues.

As a result, finding a practical policy response to Russian aggression in Georgia and Ukraine — or to actions like the assassination of Aleksandr Litvinenko on British soil, or the increasing hostility that U.S. diplomats face inside Russia — is challenging for policymakers. Ultimately, Moscow's behavior carries few costs for the United States. In contrast, any cost-benefit analysis would argue strongly that the risk and potential costs of a conflict with Russia dramatically outweigh the possible benefits of drawing Ukraine closer to the West. Put simply, Russia will always have more at stake in Ukraine than the United States does.

For all these reasons, diplomacy remains the best approach to resolving the many challenges posed by Russia, including the Ukraine crisis. The Minsk process has been slow, driven by the willingness of French and German diplomats to take the lead, yet it still offers the best chance for a peaceful resolution to the conflict. Offering sanctions relief in exchange for successful implementation of the Minsk process could contribute to diplomatic success. But it is also important to be realistic about what can be achieved through diplomacy and sanctions. Crimea is lost to Ukraine, and although the Minsk process can likely stabilize the rest of the country, Ukraine will have to weigh for itself the costs and risks of future conflict with Russia against the benefits of joining either NATO or the European Union. Neither Crimea nor a neutral Ukraine presents a major loss for U.S. interests; yet accepting these unpleasant realities is likely to be unpopular, particularly among those who see NATO less as a mutual defense pact and more as a mechanism for incorporating and socializing democratizing states in Eastern Europe into the transatlantic community. There are other obstacles too: Russia's role as aggressor often obscures the fact that Ukraine's elites remain corrupt, disorganized, and often unwilling to make necessary political reforms. To succeed, pressure must be brought to bear not only on Russia, but also on Ukraine's government to fully implement the political provisions of the Minsk process, including local elections in the Donbas.

Some other concrete policy solutions may prove useful. Though current sanctions have been largely ineffectual, sanctions that focus on impeding military modernization are likely to be more useful than those aimed directly at Russia's leaders. Indeed, the combination of sanctions on electronic components and the shutoff of military trade with Ukraine — which was a major supplier of engines for military use — has impeded Russia's ability to manufacture helicopters and frigates, as well as some ship and heavy-lift capabilities. By making it harder to obtain high-tech components in particular, military-industrial sanctions can weaken Russia's ability to fight in the future.

Continuing diplomatic work with Russia, independent of ongoing events in Ukraine, has the potential to yield agreements that likely couldn't be achieved otherwise — as the Iranian nuclear deal highlighted. While Russia certainly does not — and should not — possess a veto on U.S. foreign policy objectives around the world, the Syrian crisis has powerfully illustrated Russia's ability to make life more difficult for the United States if it so chooses. Moving forward, Russian diplomatic support will be particularly valuable in pursuing a solution to the crisis in Syria, given Moscow's strong influence over the Assad regime.

Russia's behavior in Ukraine has been deplorable. Yet it is also a striking illustration that — however we may pretend otherwise — U.S. foreign policy tools cannot always force other states, particularly major powers, to act as we wish. When the benefits of increased U.S. intervention in Ukraine are compared with the costs of a potential conflict with Russia, it is clear that military solutions are not viable. At the same time, continued poor U.S.-Russian relations have the potential to cause future conflict and to undermine U.S. foreign policy objectives elsewhere. Instead of seeking to ratchet up tensions, therefore, policymakers should continue to pursue a diplomatic solution to the crisis in Ukraine, focus on inhibiting Russia's military modernization where possible, and seek a constructive working relationship with Russia on non-European diplomatic issues, such as nonproliferation and ending the Syrian civil war.

Suggested Readings

Ashford, Emma. "Not-So-Smart Sanctions." Foreign Affairs 95, no. 1 (January-February 2016): 114-23.

Foreign Affairs. "Should the United States Arm Ukraine? Foreign Affairs' Brain Trust Weighs In." Foreign Affairs, February 24, 2015.

Sakwa, Richard. Frontline Ukraine: Crisis in the Borderlands. London: I. B. Taurus, 2015.

Sarotte, Mary Elise. "A Broken Promise? What the West Really Told Russia about NATO Expansion." Foreign Affairs 93, no. 5 (September-October 2014): 90-97.

Sokolsky, Richard. "Not Quiet on NATO's Eastern Front." Foreign Affairs, June 29, 2016.